The Temple of Amun at Karnak

The Text of an intended Appendix for Robert Bauval's then 'Egygt Decoded', book now renamed ' The Egypt Code'. The Appendix was submiited January, 2003.

The appendix was rejected and is published here in an updated form; although the bulk of the text is essentially unchanged

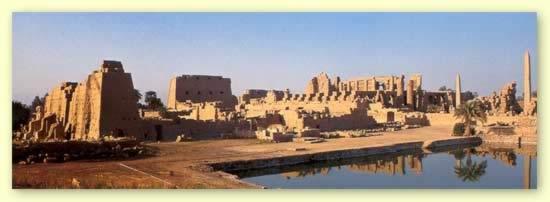

The Impressive remains of the great Temple of Amun at Karnak in Southern Egypt lie

Some 66O Km, South of Cairo.

Known to the ancient Egyptians as ‘Ipet-Sut’, ‘The most Select of Places'. Karnak is located at 25deg 43min N, 32deg 40min E.

Karnak was and still is one of Egypt’s major Temples and despite ravages dating from the attacks of the Assyrians, Persians, Christians and finally, the Egyptian authorities in the Nineteenth century; it retains much of its grandeur.

The main temple consists of a series of gateways, courtyards, pillared halls and splendid obelisks laid out along a central West-East main axis leading to the Holy of holies of Amun.

There is also a secondary north-south axis linking the main temple to that of the goddess Mut, Amun's divine consort and a member of the Theban Triad. The third member of the Triad is Khonsu, a moon god. The Khonsu Temple is within the precinct of Amun. Temples are here also dedicated to Osiris, Ptah, and Monthu amongst the shrines of other guest deities.

The remains standing at Karnak today are largely the result of the explosion in building activity on the site following the defeat of the Hyksos circa 1570 BCE. Amun, patron God of the victorious Theban princes, became the beneficiary of the spoils of war. The Kings of the new 18th dynasty honoured their God with great wealth, prestige and the undertaking of a major expansion of Ipet-Sut.

In common with evolved sites, what we see before us today is not the whole story of Karnak. When the New Kingdom kings began rebuilding Ipet- Sut, within a short time they had completely destroyed the Middle Kingdom Temple of Amun. All that remains of this Temple of Amun, the original ‘Ipet-Sut’, are some in situ remains of Senwosret I behind pylon VI and a reconstructed heb-sed kiosk belonging to the same king.

Certainly the evidence informs us that the Middle Kingdom temple occupied the site, which houses the New Kingdom Sanctuary of Amun and the great festival hall of Thuthmosis III. This Festival hall of Thuthmosis built to celebrate his jubilee, is to the East of the sanctuary and aligned on the main axis of ‘Ipet-Sut’.

Given the position of the Middle kingdom remnants, we can be assured that the main axis of new Kingdom ‘Ipet-Sut’ does indeed remain faithful to the MK axial line, Senwosret’s in-situ building fragments confirm this. Indeed, evidence from the festival hall of Thuthmosis III which leaves no doubt about the existence of a MK Temple, also hints strongly at the lost presence of Old Kingdom shrines here as well. As there are no remains of an Old Kingdom temple in existence, the evidence we have for its reality comes from the Karnak King list inscribed in the festival hall by Thuthmosis. From these inscriptions and the fragments of statues found on-site, we have compelling evidence that Old Kingdom shrines once occupied this site. Interestingly, the architectural features in the detail of the hall of Thuthmosis show archaic features. These features had not been used in buildings since the time of the Old Kingdom.

Besides this obvious link to a more ancient past, we can now consider the Karnak king list.

With this list, Thuthmosis honours a select number of ancient kings, and it is safe to assume that the reason for this remembrance was because Thuthmosis had removed their works to make way for his festival hall. As we know the hall occupies that part of the site associated with the earlier temples, we are on safe ground here. There are many kings in the list including Thirteenth and Seventeenth dynasty rulers, however of great interest. Here are the seven Old Kingdom rulers: Sneferu, Sahure, Niuserre, Djedkare, Teti, Pepi (I) and Merenre. Taken together, they represent a period from the Fourth dynasty through to the Sixth Dynasty.

There is no particular reason that Thuthmosis should name these Kings, unless it was their monuments that were the basis of the Old Kingdom Temple and had to be cleared for his great hall of festivals.

That Niuserre had monuments on the site is given further confirmation by the fact that a statue in British Museum (EA 870) of Senwosret I from Karnak has a cartouche of Niuserre inscribed upon it. Also found in the Karnak cachette was the lower part of a statue of Niuserre, this King ruled in the fifth dynasty c.2445-2414bce and surely there is no reason for this statue to of been on site other than it was once set up here in a shrine.

As no remains of the Old Temple exist, we cannot be sure which deity these Old Kingdom Kings honoured. As Amun was known in the Old Kingdom, and given that Senwosret is one of the founders of Ipet-Sut, we can assume that it was a primeval Amun prior to his attaining and absorbing attributes of other gods during his meteoritic rise to power. It follows from the realisation that an Old Kingdom temple was once in existence at Karnak that an archaic period shrine would have also existed here far back in the most ancient times. There is plenty of evidence in the district of Thebes of activity from this period and therefore the probability of an archaic shrine is extremely high. I have no doubt that such an ancient shrine would have been dedicated to sky gods, those connected with fertility and the night skies, the constellations.

The evolution of Karnak is certainly reflected and connected to the change of constellation marking the Spring Equinox. Before the rise of Amun in the 12th dynasty, the god Monthu was the principal deity worshipped at Karnak. Monthu was a war god, and a sky god, a bull connected to thunder. Monthu was the patron God of the Kings of the 11th dynasty who bore his name, such as Monthuhotep. As a bull god, it is important to note that Monthu was predominant at Thebes during the age of Taurus, Taurus of course being the constellation identified with the bull.

The change in constellation marking the spring equinox (precessional effect) occurs when Aries replaces Taurus. Aries associated with the Ram, which just happens to be Amun’s sacred manifestation.

So, as Taurus gives way to Aries, the Ram replaces the bull, the Monthuhoteps are replaced as Thebes and Egypt’s rulers by kings who follow Amun with his sacred ram. The First King of the 12th dynasty was named Amenemhat, which means ‘Amun is supreme’. At this point in time, it is worth mentioning that Amun absorbs much of Mouthus attributes, as he already done with the god Min during the First Intermediate period. Amun’s nature is now associated with sky phenomena such as Min's thunderbolt, Min's meteors and Monthus’s fertility and bull associations.

Some scholars maintain that is Amenemhat I who began building ‘Ipet-Sut’, others that was his successor Senwosret I, certainly the first occurrence of the name ‘Ipet-Sut’ is from the reign of Senwosret I. On balance, I think it is quite likely that Amenemhat began the works at ‘Ipet-Sut’ and Senwosret added to the Temple considerably more shrines. This scenario would fit well with the sequence of events concerning the change from Taurus to Aries, the rise of Amun and his new patron kings. The 12th dynasty came to power in 1991bce and closed around 1783 BCE.

In 2150 BCE, Aries the ram coincided with the first stars of Taurus the bull, displacing Taurus gradually as the equinoctial marker. By 1754 BCE, the bright star Hamal in Aries was rising with the Sun on the vernal equinox at Karnak. Certainly the early centuries of Aries as the spring equinox marker sits remarkably well with Amuns rise in prestige. So, thus the rise of Amun is no coincidence, but can be seen as result of the change of constellation marking the vernal equinox.

Mythological, Karnak’s founding is based on the great creation myth of Egypt itself.

The Temple of Amun symbolically represents the place and occasion of the creation.

Each of the important theological centres in Ancient Egypt had its own version of the same myth.

To the Egyptians, this wasn’t a problem; they were all simply different ways and places, which in their own way described the same event. All the gods are but manifestations of the one supreme creator god. At Karnak, it is Amun who is the first one of creation, at Iunu it is Atum, at Memphis it is Ptah and at Hermopolis it is Thoth.

The earliest developed theology was that of Iunu, and Karnak is seen, as it’s double, often referred to as Southern Iunu. The temples of the gods in these places were considered to be the original sites of creation, known as the First Occasion or Zep Tepi.As such they were the primeval mounds, which were the first land to arise from Nun, the primeval ocean of chaos. Upon this mound, the creators performed the miracle of turning his oneness into two, thus beginning all life on Earth.

The Theban Theology stated that Amun was the supreme neter of god, from whom all gods were manifestations of his divine will. Karnak Temple itself was the site of the mound of the first occasion; this is made clear in an inscription of Hatshepsut taken from an Obelisk of the Queen standing within Ipet-Sut:

“I know that Karnak is the horizon (3ht) of heaven upon earth, the august high ground of the first occasion, the sacred eye of the Lord of the Universe, his favourite place of raising his crowns”. ( Bjorkman, Uppsala,1991)

Karnak was also known as the favourite place of his (Amun) risings. In Theban theology, Amun is amongst his many other aspects, Ta-tenen, the primeval mound itself. Thebes was thus claimed to be the first city and the pattern for all cities to be modelled upon. The priests also claimed that Karnak was the birthplace of Osiris, and this claim concentrated all creative and regenerative forces within Ipet-Sut.

As a Temple, Karnak was conceived to be the place of creation and the home of its creator god, Amun, the primeval one. Not only is Karnak the site of the creative event, in common with all temples in Egypt, it is also a model of the cosmos. As a microcosm, its alignments related to the Sun, Moon, stars and planets. These alignments are crucial if the temple is to function as a meeting point between heaven and earth, between the world of humans and the celestial world of the gods.

Karnak’s prominent main axis celebrates the union of divine and earthly power.

This main east-west axis was once thought by Lockyner to be orientated westerly towards the setting Sun on the Midwinter solstice. The research of Gerald Hawkins suggested that in fact, the orientation was eastwards and that this line in 2000 BCE-1000 BCE would have indicated the Midwinter sunrise. This dating of Hawkins fits in well with the Middle Kingdom axis, which the New Kingdom axis certainly follows. Although this means that Karnak’s main axis is solar in that it is concerned with the solar motion and the turning point of the year, the victory of light over darkness, we can rest assured that other alignments are built into Karnaks fabric.

The foundation ritual of the Temple bears this out, and strongly suggests that stellar alignments exist throughout Ipet-Sut.. These rituals involved the marking out of the temple boundaries, by the king or his high priests accompanied by spells, and the chanting of sacred prayers. We know that the ceremony was carried out at night under the stars, and the constellations of Ursa Major, Orion and the new Moon were used in the setting out procedures.

We have noted that Karnak’s lineage is perhaps most ancient, the high probability of an archaic shrine, and the tantalising remnants of the Old Kingdom temple. Much has been achieved in seeking out Karnak’s secrets, yet much more research is still required and we look forward to new discoveries.

Looking back in time, John Baines (The Temple in Ancient Egypt, ed, Stephen Quirk, BMP, 1997) wrote a most informative comment regarding the beginnings of the temple:

“It is most prudent to assume that the gods and places in which they were worshipped formed part of the cosmos and the society of pre-dynastic Egyptians, and hence that developments towards forms known from dynastic times built upon conceptions that were already ancient”.

Ipet-Sut then is the place par-excellence where space and time come together. The myths and rites were here enacted which linked the first time to the present. Order and Ma’at were the blessings of Amun, and this temple existed to ensure that Amun continued his benevolence upon Egypt.

Bibliography of Prime Sources

Baines John and Malek Jaromir, Atlas of Ancient Egypt Phaidon, 1998 Ed

Ingpen Robert and Wilkinson Philip, Encyclopedia of Mysterious Places, BCA, 1990.

Ion Veronica, Egyptian Mythology, Hamlyn, 1968.

Hart George, Egyptian myths, BMP 1990.

Kemp Barry J, Ancient Egypt, Anatomy of a civilisation, Routledge, 1991

Lubwicz Schwaller De, The Temples of Karnak, Thames and Hudson, rev Ed, 2000.

Molyneux Brian Leigh and Vitbeksky Piers, Sacred Earth, Sacred Stones, Duncan Baird, 2000.

Sellers Jane, The Death of Gods in Ancient Egypt, Penguin, 1992.

Shaw Ian, Ed, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, OUP, 200

Shafer Byron, Ed, Temples of Ancient Egypt, Cornell University press, 1997.

Strudwick Nigel and Helen, Thebes in Ancient Egypt, BMP, 1999.

Watterson Barbara, Gods of Ancient Egypt, Sutton Publishing, 1996.

Ian Alex Blease: 15th Jan 2003: Updated 5th Dec 2005