|

| ON THE FLY US Weekly 12/4/2000 By Natalie Nichols It's four hours before showtime and the Dixie Chicks are still in their pajamas. The pop-country trio are backstage at Pittsburgh's Mellon Arena, a stop on their six-month national tour supporting Fly, their Grammy-winning second album, which has sold 7 million copies. Since they rarely step out in public looking anything less than rock-star glamorous, it's shocking to see them hanging around, without a bit of makeup, in sweatpants and T-shirts. "We got up so late today!" says Emily Robison, 28, the group's down-to-earth master of the banjo and dobro (a metal-and-wood acoustic guitar). She's almost unrecognizable with her wavy dark-brown hair pulled back in a ponytail. She and her sister--smart, sensible blond fiddle whiz Martie Seidel, 31--have started the day with their usual routine: 90 minutes of yoga with Vanda Mikoloski, their traveling instructor and masseuse. Instead of joining the workout, lead singer Natalie Maines is spending the afternoon in bed on the Chicks' tour bus. Yesterday was her twenty-sixth birthday, and her husband of four months, Adrian Pasdar, the star of NBC's Mysterious Ways, surprised her by showing up at the band's Philadelphia concert. After traveling with Maines overnight to Pittsburgh, he flew back early in the morning to Vancouver, British Columbia, where his show is filmed. At 5 PM, Maines walks through the stage door looking like a rumpled, sleepy pixie. She's four months pregnant and gets tired more easily on the tour these days. Lately, she says, it has been a struggle to fit into her stage clothes, but at least she hasn't been troubled by morning sickness. "I couldn't do this out here if I was sick," she says of life on the road. Onstage, Maines is the charismatic dynamo who brazenly advocates "mattress dancing" in the song "Sin Wagon" and cheers the demise of and abusive husband in "Goodbye Earl," a comic depiction of murderous revenge that sparked protests from some conservative country-music fans and radio stations. But in real life she's not so bold. "I get really shy in new situations, " says Maines as she receives a foot massage from Mikoloski. "Adrian's family was at the show last night and I'm sure they were surprised watching me onstage. Around them I'm this really quiet, nice girl. And there I was, showing off for thousands of fans." Since the Chicks usually sleep in their tour bus while on the road, they like to make themselves and their crew comfortable. Trucks that accompany them carry the components of an elaborate beauty salon (couches, rugs, scented candles and a TV/VCE), which gets constructed backstage at each concert stop. The Chicks really are a traveling family that takes pride in its solidarity. Maines, Robison and Seidel each have nine tiny chicken feet tattooed atop their feet--one for each gold record and number-one single they have had. (There should be 11, but Maines can't be tattooed while pregnant, so they're all waiting.) The Dixie Chicks grew to be a country-music phenomenon by mixing sweet good looks, sassy attitudes and outrageous stage costumes with genuine instrumental prowess and intricate vocal harmonies. They have earned enormous pop-crossover success, yet they're authentic enough to please the Nashville Establishment--in October they took home four Country Music Awards (adding to the five they won in '98 and '99) including Entertainer of the Year. Sales of their 1998 major-label debut album, Wide Open Spaces, recently topped 10 million, and the Fly tour had reportedly grossed more than $38 million by the end of October, making them the seventh-richest act on the road. Still, it has been a long haul. The Dixie Chicks' early blend of traditional blue-grass and Western swing was rooted in Robison and Seidel's Dallas upbringing. Their schoolteacher parents, Paul and Barbara Erwin, encouraged them to pursue music lessons. "All my rich friends had Atari and were allowed to watch TV after school. We never could," says Seidel. "Then, I thought it was a bummer, but now I'm glad." Both sisters became preteen bluegrass prodigies. They played in bands and competed at festivals, to whcih their whold family traveled by RV. Still, having such involved parents wasn't always a blessing. "When I was 12 or 13, my mom arragned for my first band to play for the seventh and eighth-grade classes at school," says Seidel. "I just didn't know how to say 'No way, Mom!' It was mortifying. Bluegrass was something I did outside of school. Nobody thought it ws cool." Bluegrass still wasn't cool when Seidel and Robison officially formed the Dixe Chicks with their friends Robin Lynn Macy and Laura Lynch in 1989. But they made a few bucks playing in small clubs in Dallas and released three independent albums. By 1994, Robison and Seidel had grown dissatisfied with their oldfashioned country sound. Veteran steel-guitarist and occasional Chicks sideman Lloyd Maines gave them a copy of his daughter Natalie's music-school audition tape. In 1995, after parting ways with Lynch (Macy had left the group in 1992), the sisters asked Maines to join. She didn't hesitate. "If anyone wanted me to sing, I'd clear a table--I just needed a stage," says Maines. "Baskin-Robbins, my mom's office, wherever." When Maines joined the Chicks, she lent the trio a contemporary sound that blended intriguingly with their traditional instrumentation. "Martie and I [finally] had another person with the same vision," says Robison. After the tour ends on December 3 in Fort Worth, Texas, Maines plans to wed Pasdar--for the second time. The couple met and quickly fell in love when they were paired up as bridesmaid and groomsman at Emily's May 1999 wedding to country singer Charlie Robison. They had a quickie ceremony last June during a Las Vegas tour stop. "Our families haven't met yet," says Maines. "So we're going to take them to France at Christmas and get remarried over there." By then she'll be in her sixth month. They will learn the baby's gender somteim in November; she has already picked out names. "If it's a boy, I think it's Jack Slade," she says. "If it's a girl, Lillian Marie." The couple have apartments in New York and Los Angeles but plan to buy a house in Austin, Texas to be near Maines's parents and sister when the baby comes. Now that Maines is pregnant, Robison has been thinking about starting a family. ("Emily is hopefully going to become a mom when we're off tour," says Maines, "so we'll have that in common.") But for now Robison is looking forward to returning to San Antonio, where she and her husband are planning to build a ranch in the hill country near their current house--and where the two spend as much time as possible riding the horses that they gave each other for their August birthdays. Robison says her appaloosa, Chino, was originally her husband's, and his quarter horse, Jett, was for her. "But mine threw me off the first tiem I got on," she says. "I was a little bit to aggressive and [as a result] got four stitches put in my head. It was a mess!" Now she's riding Chino. "but I have my war story, you know? I feel like a real cowgirl now." Robison is the perennial tomboy. "I've always done thigns to keep up with the boys," she says. "Like playing banjo. No girls were playing banjo when I was growing up. And I loved sports when I was in high school." Volleyball and soccer, along with her music, became a refuge for Robison when her parents split up when she was 15. The sisters found out that their father was seeing another woman on the day before Seidel went off to college (their older sister, Julia, was already in college)--leaving Robison alone to deal with the sad new situation at home. "To a fault sometimes, I compartmentalize my life," Robison says. "That's my defense mechanism." Robison and Seidel later wrote "You Were Mine," a heartfelt ballad about the experience, for Wide Open Spaces. It was the first Chicks song Maines ever sang. Martie Seidel doesn't radiate the self-assuredness that Robison and Maines share. She's more of a mother-hen type, overly worried about others' feelings. After the tour, she plans to buy a new house and start over again--in Austin. Seidel filed for divorce from her husband of four years, pharmaceutical sales representative Ted Seidel, in Novemeber 1999, just as the Chicks' career was reachign a critical juncture. The trio were recording Fly in Nashville while Seidel's husband was eager for her to attend couple's therapy in with him in Dallas. "I had played all htose sh--ty gigs for so long and been our tour manager and drove the RV and all that. I felt like 'This is my shot,'" she says of her agonized decision to put her career first. "At that moment, I wished I didn't have the baggage of a marriage that was going downhill," she says. "He had always been so supportive of me. But I wanted to escape and dive into making the album." It's a half-hour before showtime and the Chicks stride confidently out of their dressing room for the ritual fan meet-and-greet. The pajamas are long gone; the transformation is complete. Maines wears a bronze leather shift and high boots; Seidel, brown leather pants and a glittery purple tank; and Robison, the most over-the-top, a burgundy halter and tan hip-slung pants fringed with hundreds of jingly little bells. What hasn't changed is the genuine camaraderie among them. "We're the only people who live this life and we know what it's like," says Maines simply. "We're like sisters." |

|

|

|

|

| THE WAY WE WERE: Singing the National Anthem and a Rangers vs. Yankees game in 1996. |

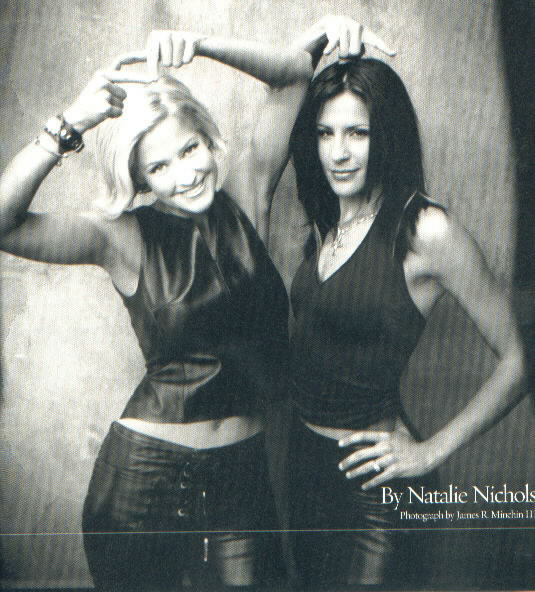

| MARRIED CHICKS: Maines (left) and Seidel (right) at Robison's wedding in May, 1999. |