|

On the other hand, if Pavarotti could have been persuaded to sing a song for the fortnight's play, the most appropriate would have been: ``We'll meet again''. Edberg and Becker did so for the third time in a row in a men's singles final, and Graf and Navratilova were only prevented from fulfilling their tryst by the surprising excellence of Zina Garrison.

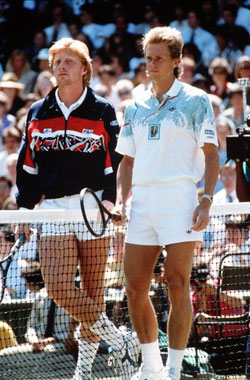

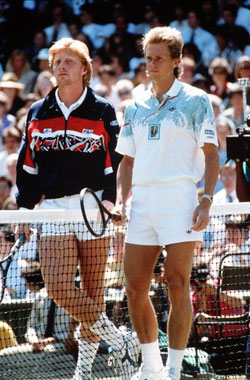

Barring catastrophic injury or mental aberration, there is no reason why Becker and Edberg should not continue their long-standing relationship in the final for the next three years as well, thereby surpassing the record set by Joshua Pim and Wilfred Baddeley in four successive years between 1891 and 1894. The pair are by a very wide margin the two best grass-court players in the world. Yet, their rivalry does not quicken the pulse quite as much as McEnroe v Borg or Connors v Borg. McEnroe and Borg were made for each other; contrasts in every way, in style and character, background and training, united only in the strength of their wills and the depth of their respect for the other.

Edberg and Becker have mutual respect, perhaps too much of it at times, but because they are both consummate serve-and-volleyers they do not provide that contrast. When one plays well, almost by definition the other one cannot. Rather than darting hither and thither, therefore, their matches rumble one way and then, as was the case on Sunday, the other, before reaching a thudding conclusion. Still, it is a pleasure just to watch Edberg's service action, which seems to defy the laws of physics and bio-mechanics at the same time; the nimbleness of his footwork and the deftness of his volleying.

Having survived an early scare against Amos Mansdorf and Becker's inexorable comeback in the final, he is a worthy champion.

There were other delights to savour as well, but they were all too brief in the case of the women. Jennifer Capriati played one sparkling match against Robin White before succumbing to the careworn Steffi Graf, and Monica Seles, two years older but not that much more experienced on grass, found that her game lacks the variety to cope with a natural grass-court player in peak form. Garrison showed up the limitations in the Yugoslav's game and, more surprisingly, in Graf's too.

Graf must regroup and find some new goals. That will be hard because she had reached 13 grand slam finals before her 21st birthday. At the moment, she is weighed down by cares about her father, whose private life continues to fill the gossip columns, and by basic flaws in her game.

Despite her protests to the contrary, Graf has lost enthusiasm, such a vital part of her game. She has also lost her aura of invincibility. The latter might be harder to recover. Perhaps she could take inspiration from Navratilova, who has persevered until she claimed the record with her ninth title. ``I can just about imagine winning one,'' Garrison said, ``but nine ...''

Navratilova will be back next year; so will Ivan Lendl. Lendl needs to find the male equivalent of a Garrison in the final if he is ever to win Wimbledon, because he does not have the physical or tactical flexibility to cope with either Becker or Edberg at Wimbledon.

He seemed to gain hope from his display against Becker in the final of the Stella Artois tournament the week before Wimbledon, ignoring the fact that Becker and Edberg are not interested in winning at Queen's, only at Wimbledon. Lendl has indicated that he will start his grass preparations even earlier next year.

Of the new names in the men's ranks, only Goran Ivanisevic really enhanced his reputation. He troubled the commentators throughout the fortnight and, like his countryman, Slobodan Zivojinovic, will surely be back to twist tongues for a few years yet. It could have been worse, however. One of the boys in the junior singles was called Umeshta Wallooppillai. He comes from Sri Lanka.

Leander Paes, the junior champion, comes from India, and is a product of the Vijay Amritraj tennis school in Madras. In the juniors there were also nine Japanese, four Thais, three Koreans, two Indonesians, two Chinese and one player from Taipei. What odds a Wimbledon champion from the Far East before the turn of the century?

Rather better than those for a British champion, I fear. The British challenge was statistically the worst on record, all 16 home players having been knocked out before the third round in the singles, though Bates, Brown, Botfield and Turner salvaged some respectability in the doubles. With Sarah Loosemore and Samantha Smith, the horizon looks more encouraging for the women than the men and, it is hoped, new sponsorship by Rover, worth Pounds 600,000 over the next three years, will be money profitably invested.

Perhaps the following figures will provide an incentive for any prospective champions. Based on an average of four strokes a point, seven points a game, ten games a set and four sets a match, every shot that Stefan Edberg played over the past fortnight was worth Pounds 30.