The Edberg of old - that is, 18 or early 19 - would probably have crumpled right then. "Depression," as he candidly calls it, would have taken command and, glowering and muttering, his head drooping like a dejected schoolboy, he would have gone on to squander the greatest opportunity of his career. As his coach, Tony Pickard, later reflected, "Those missed match points would've gotten to him something awful."

But the new young Edberg is not the old young Edberg. Pulling himself together promptly and calmly, he proceeded to defeat Lendl 9-7 in the fifth. Then in the final two days later, he completed the greatest week of his life by steamrolling fellow Swede Mats Wilander 6-4, 6-3, 6-3.

Two weeks after that, in the deciding match of the 1985 Davis Cup final, Edberg recorded another extraordinary victory, overcoming West Germany's cannonballing Michael Westphal, 13,000 roaring hometown fans in Munich and his own acute nervousness to retain the Cup for Sweden. All of these heroics, it turned out, were performed in the face of developing mononucleosis, which Edberg's lean, lithe body had been harboring for several weeks. A touch of mono, it seems, would he good for all of us.

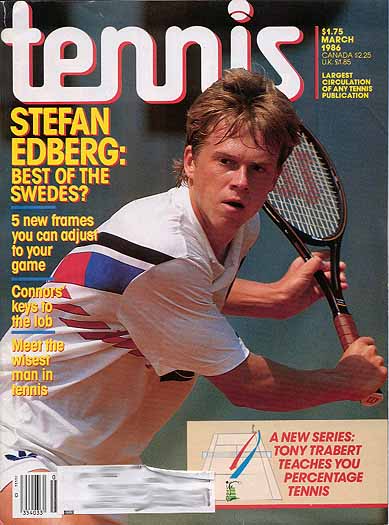

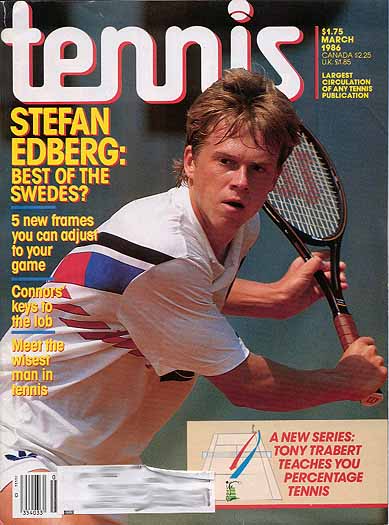

As the holder of a Grand Slam singles title and the hero of Sweden's championship Davis Cup team, Edberg now stands with Boris Becker as the hottest young player in the game. Indeed, the reserved young Swede is now emerging from the shadow of such countrymen as Wilander, Anders Jarryd, Joakim Nystrom and Henrik Sundstrom, and threatening to overtake them all as the best of the Swedes.

His victory over Wilander, the two-time defending champion at the Australian Open, is one indication of that. So is his fiery ambition. Much has been made of Wilander's wavering interest in gaining the summit of men's tennis. But Edberg, now 20, expresses no such diffidence. Far from it; he hungers openly for the top and will not be satisfied until he gets there. As Erik Bergelin, Edberg's agent, notes, "Stefan even turns down exhibitions so he can concentrate on winning tournaments and climbing in the rankings."

Now ranked No. 5, Edberg is also more demonstrative than most of his fellow Swedes. He's never boorish on the court, but it's easy to tell that fire burns beneath the placid exterior. He customarily reacts to errors by grimacing and spitting out an expletive that's sure to be a Swedish version of an Anglo-Saxon four-letter word. Asked what the word is, he grins and replies, "It's not very nice - but it's not very loud."

This Swede who would be king was born and raised in Vastervik, a coastal resort town about 175 miles south of Stockholm. His father was, and still is, a plainclothes policeman. Young Stefan excelled at tennis and early on developed a serve-and- volley style that immediately set him apart from all the baseline topspinners imitating Bjorn Borg. "I always practiced a lot on my serve," he recalls, "the second as well as the first. And I always liked to volley." Nobody insisted that he couldn't win that way on clay because, from an early age, Edberg won on that surface.

At 14, he developed another stylistic distinction: a one-handed backhand. Since Borg had become a deity, the two-handed backhand had ruled Swedish tennis. Every kid with any prospects had one. So did Edberg for six years, but he was never happy with it. "The stroke got worse, especially as I got taller," he says, "because I couldn't get down for low balls."

Percy Rosberg, his coach, saved him. Rosberg had been instrumental in training Borg to hit with two hands on the backhand. Now, with another prodigy, he had the rare good sense to see that the opposite approach would work best. Many other experts, real or fancied, didn't agree. There were howls in the Swedish press and among Rosberg's fellow tennis teachers. As Edberg remembers, the change looked especially bad for a while, "because everybody started playing my new backhand."

Now that's all a bit of ironic tennis history. Edberg today has an excellent backhand. He returns and passes better off that side than off the forehand, a stroke that remains slightly suspect.

At 17, Edberg had already written his name in the tennis history books by becoming the first, and so far, only player to win a junior Grand Slam. Oddly, considering what's happened since, his chief opposition came from Australia's Simon Youl and John Frawley; he met Becker only once, defeating him at the junior Wimbledon.

Shortly after Edberg turned pro in 1984, Rosberg stepped aside as his coach because commitments at home prevented him from traveling the international circuit. In his place, Pickard, a leading British player of the 1950's and later coach of that country's Davis Cup team, took over tutoring Edberg. Pickard made the unusual decision not to tamper with technique. "I think it's wrong to do that at Stefan's level," Pickard says. "As far as strokes are concerned, what he has, he has. In a match, I don't want him thinking, 'I've got to do X or Y the way Tony showed me.' [Great advice from Pickard. At pro-level, technique is very difficult to change - Ed]

"People make comments about supposed weaknesses in Stefan's game (a veiled reference to his forehand), but I'd never dream of mentioning that to him. If he thinks I think he has a weakness, we've got a problem. I'd never say, 'I think you should change your grip or swing that way.' At this stage, you could destroy somebody doing that."

Pickard does work hard on tactics: "We sit down before a match and talk about how we see it. Before he met Lendl in Australia, for instance, I said, 'You've got to play your own game and not let Lendl impose his on you.' He can do that, but Stefan was pretty well able to avoid it."

Pickard has worked hardest on, or in, Edberg's head. "The boy was very shy," Pickard says. "There's nothing wrong with that, but if you're going to be, or attempt to be, No. 1, you need some toughness to go with it. Stefan had a real habit of getting depressed on the court, dropping his head."

The remedy? Just common sense and repetition: "I told him more times than I want to remember, 'When you lose a point, it's history. Forget it. And when you drop your head afterward, the guys at the top know you're down on yourself, and that may he just the edge they need to beat you."'

The hangdog attitude, Edberg says, afflicted him most "when I'd played a long match and was tired and hadn't gotten some things right all along. Tony got me to think positive, and that's the most important point for my game. Before when I got depressed, I'd find myself holding back, not going for my shots." Attitude aside, that can be fatal to an attacking player.

Clay is the Swedish surface, the one on which Edberg honed his serve-and-volley game. He has had some excellent clay-court results, especially in 1985 when he reached the final of the Swedish Open and the quarters of the French. But Edberg still needs to add patience and variety to his slow-court game. "If you're going to beat the guys at the top," Pickard observes, "you can't play the same way against them day in, day out."

According to Wilander, Edberg has already increased his backcourt steadiness. "Even when Stefan is playing badly now, he's still in the match," Wilander says. "He's become a lot steadier." Credit for that goes to Pickard's lessons in positive thinking.

Some experts, however, doubt that Edberg's backcourt progress has been that substantial. Lennart Bergelin, Borg's longtime coach, thinks Edberg still needs to place more emphasis on ground strokes: "I saw John McEnroe learn that against Bjorn. At first, he didn't believe in his ground strokes. But to beat Bjorn he had to develop them so he could stay in some points - rather than come in all the time and get passed at the service line." Despite his big victory on Australian grass, Edberg says he prefers to play indoors on Supreme Court. But he has the game to win on any fast surface. Excepting McEnroe when he's sound, Edberg may well be the best volleyer in tennis. He's certainly the most fluidly graceful. His balance is exceptional, and he plays volleys effortlessly and effectively from any position. McEnroe may have slightly better reflexes at the net, but Edberg has awesome lateral speed. No matter where the passing shot is aimed, he seldom fails to get a racquet on it.

Coupled with his volleying, Edberg's serve is particularly effective. He doesn't serve many aces or even outright winners. What he does do is serve deep with good speed and spin, setting up lots of first-volley winners. Against Westphal in the Davis Cup, he ran off strings of points that way.

His second serve is even more impressive, probably the best in the game today. The ball lands so deep so consistently that it looks as though he's literally aiming for the service line. Thus, it was a sure sign of nervousness when he lost the first set against Westphal by hitting a second serve into the net.

Like most of the top Swedes, Edberg has become an expatriate for tax reasons. But he has opted for London, rather than Monte Carlo, to be nearer his Vastervik home and closer to Pickard. Edberg remains close to his parents. His father serves as his unofficial advisor, and his mother decorated his two-bedroom London flat - trying in the process to soften her son's taste for modern, functional decor.

Off court, Edberg has many of the tastes and habits of a teenager, albeit a wealthy one. He enjoys cruising about in his recently purchased BMW. He brings a tape player and tapes wherever he goes, listening intently to the group and beat of the moment.

Beneath these trappings, however, lies an unusual maturity. Edberg not only abstains from alcohol, he also avoids junk food - a category he enlarges to encompass hamburgers and sausage. His reason is simple: He thinks they're harmful to the body. He scrutinizes,his prospective contracts to make sure he won't he seen as endorsing any product or lifestyle that violates his values. He recently okayed a deal to appear in print ads for BMW and he also has an endorsement with Pripps Energy & Health Drink.

Edberg blends in well with the remarkably homogeneous and friendly Swedish group. Before the Australian final, he and Wilander breakfasted together and then - to the astonishment of tournament officials - warmed up together. To Edberg, that was only sensible: "We are good friends, and I'm not going to kill myself if I lose and neither is Mats." When the two walked off court after the final, both were smiling and Wilander patted his victorious buddy on the shoulder.

Karl-Axel Hageskog, a Swedish team coach, has watched Edberg and Wilander develop since they were youngsters. Asked what Edberg needs now to reach the top, Hageskog replies, "Stability, consistency in his whole game. As it is, anything can suddenly stop working for him. He doesn't have stability the way Mats has."

Edberg shrugs that notion aside. "It's hard to tell what's still missing," he says. "But I know it's not very much, and I'm close to getting it."