I have stopped paying attention to pro-tennis since his retirement. Although I received occasional notes about him, I was determined to block out the thoughts. I had said goodbye and moved on. It was nice while it lasted and Stefan would always have a place in my heart, but I had other things to occupy my mind now.

Then, sometime during this year, I found myself thinking about him again. I dug out the video tapes of his matches from cartons that have been gathering dust.

It’s 1991 again, and Flushing Meadows in New York is once again a showcase for Stefan Edberg. On a quiet night and with the cooperation of Michael Chang, Stefan puts on a poetry of a match. He is tall and more fleshed out than his later years. He is impeccably groomed; his shirt even looks ironed. In the previous three matches his tennis has only been so-so, but on this night, in the face of an opponent in full flight, the billiance of Edberg’s game is about to blossom in the bright lights. On this night the world sees an unflappable Stefan who has an answer to every challenge: repeatedly smashing back top-spin lobs that have devastated John McEnroe in Chang’s previous match, out-running his fleet-footed opponent in impossible gets, and aiming his spinning serves with deadly accuracy. Breathtaking shots are made with pinpoint precision by both men. At times, the audience are on their feet and the TV commentators are reduced to muttering superlatives. In the end, a confident Stefan emerges with a straight-set victory of the narrowest winning margins.

And I was in love all over again.

|

Oh, it was a grand affair. I discovered Stefan too late. It wasn’t until he successfully defended his US Open title in 1992 that Edberg came to my attention. I had heard about him before, and, when I saw the broadcast of the tournament that year, was astonished to find out that, instead of the grizzled gent that I had envisioned, Stefan Edberg was a youthful athlete in full physical glory. I was in graduate school then, and Stefan Edberg became an indulgence, an obsession that helped me cope with the tedium of academic research. The archive of the newsgroup rec.sport.tennis is full of my postings on Stefan – I looked at it yesterday and could not believe the torrents of words I had written during those days. Reading the postings again, I had to laugh at the gush, embarrassing at times, but always heart-felt. They were inspired musings nevertheless, and I am proud to have led and participated in many a thoughtful thread on that forum.

I read with particular interest one thread entitled “Edberg is God”. It took place in 1996, the last year of Edberg’s career, when someone, incensed by the numerous postings (many of which mine) lauding Stefan, fired off a posting that accused the Edheads – Edberg fans – of deifying Stefan. The discussion then turned into a heated debate on whether Stefan got more than his share of tribute (as compared to Ivan Lendl, for example) because of his looks.

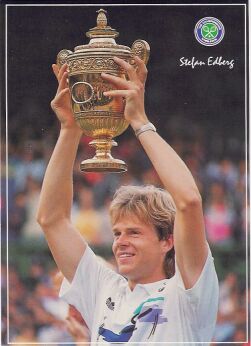

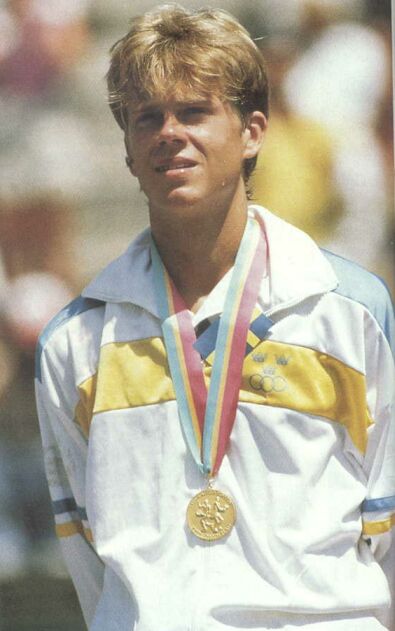

I think it is a safe assumption that Stefan Edberg is considered one of the handsomest athletes that the world has seen, and I would be disingenuous if I denied that his appearance is part of the attraction. I have the fortune of seeing a couple of Edberg matches live, and, even though I was already a fan, I could not help but noticed how he stood out among other players, everyone of them handsome in his own way. Stefan’s chiseled facial features and his intelligent blues eyes were what you noticed close up, but even from afar there was a distinctiveness in his tall, willowy figure and a poise in his carriage that set him apart from others. He had striking, muscular thighs that gave him the advantage of tremendous balance on the court. His long legs – especially when they were suntanned -- in full display under those short shorts, was a sight that brought a pang to some hearts. In the last year of his touring days, when I saw him play in Los Angeles, the words “handsome” and “beautiful” could be heard among the murmurs of the audience. Watching tapes of his Australian Open victories and Wimbledon triumphs, I often marvel at how different Stefan looked at the various stages of his career. In his early days, he was a fresh-faced Adonis with a soft flowing longish blond mane. In his two US Open glories, we saw a mature but still boyish Stefan with short, stylish hair. In later years, he would sometimes wear his hair severely short, making him look austere at times; even then, he looked very manly and handsome. One thing that was a constant is his heart-warming shy smile. In the US, TV commentators of sports seldom allude to a player’s appearance. Tony Trabert, however, could not help but remarked thus about Stefan and Annette: “You wouldn’t consider them a handsome couple, would you? Wow.” Mary Carillo, a self-proclaimed Edberg fan, jokingly said she gave admission passes to girl friends who came to the 1992 US Open to see “the cute guy (Edberg).” In the broadcast of the 1988 Wmibledon final, Dick Enberg referred to Stefan’s handsome smile at his moment of triumph, hastily adding that “they (Edberg and Becker) are both handsome, but Edberg …”.

|

Yet when I think of the Edberg that so endeared me, the image that comes to mind is that tall, willowy figure that glides effortlessly on the green asphalt, readying himself to unleash yet another spectacular shot. His famed backhand sends my heart soaring. His rapid-fire volleying never fails to thrill me. I love the sight of him backing up and climbing an invisible ladder to execute an overhead smash, his long limbs fully stretched. In his best years he would routinely scoop up shots fired at his feet with a half volley directed at an impossible angle that lands on the line, leaving his opponent (Jim Courier in the 1991 USO final, for example) glaring in disbelief. In the days when he was serving well, Stefan could launch cannon shots in the first serve, and then mischievous second serves that often result in a mishit by a puzzled opponent. In a crucial point, he would serve wide to the backhand of his opponent, leap to the net instantly in one smooth sprint, and put away a desperate return from his opponent with a decisive volley struck with such force and carved with such an angle that not even the most agile of his opponents could answer. His forehand – generally considered his weakest stroke – yielded spectacular results when he struck on the run, sending the ball in blinding speed in a trajectory that landed just on the line. His net play is legendary, but on a good day he could out-duel a Ivan Lendl or a Jim Courier in a sideline-to-sideline ground game.

|

Above all, Edberg captivated my heart because of the way he played his matches. He played an extreme serve-and-volley game the like of which is no longer seen, with an aggressiveness that stood in stark contrast with his placid demeanor. Thomas Bonk, sports writer for the Los Angeles Times, called his tennis “swashbuckling,” an apt description of the way Stefan wielded his racquet like a gladiator's sword. The swashbuckling imagery is especially vivid when he duels with his opponent at net, with the ball reverberating frantically between the racket faces of two players standing at close range, “like two gun-slingers in a Western” (Thomas Bonk again). To fully understand what I mean, you will have to have seen one particular point late in the fifth set of his 1992 US Open round-of-sixteen match against Dutch champion Richard Krajicek, himself an accomplished serve-and-volleyer. Sports Illustrated staff writer Jon Wertheim wrote, in answer to a question emailed to him in 1999: “For the most part, serve-and-volleying has gone by way of white tennis balls. I haven't seen anyone approaching Edberg's game -- here's a guy so faithfully wedded to serve-and-volleying that he would do it on second serves on clay.” Wertheim also wrote that he considers Stefan to be the all-time best serve-and-volleyer.

You wouldn’t know it from looking at his soft, placid countenance, but Stefan has a steely will that belies his apparent gentleness. He could muster that will when threatened. And often was he threatened. Perhaps because of his extreme Western grip, Stefan's game was streaky. In any given match, he could go through patches of lack-luster performance and disheartening misses that drove his fans to distraction. But just when you despaired, he would reward your patience with a flash of brilliance: an implausible volley, perhaps; or a heart-stopping backhand. And when his game was on, when he was "playing in a zone" -- as in the first two sets of his 1990 Wimbledon final or his picture-perfect 1991 US final -- it was a true feast for the eyes.

Edberg had that most elusive quality among top athletes, a quality that people in this country call "clutch": He could make a gutsy play at just the crucial point to overcome the direst adversity. There is suspense in his matches, with twists and turns rivaling the best of dramas. The blend of tennis that Stefan played seldom blew his opponents off the court, and he would torment and then reward his loyal fans with knuckle-whitening cliffhangers. Even in a match that he completely dominated, as in his 1991 US Open semifinal against Ivan Lendl, he would have one vulnerable moment when his serve wavered and he would be on the verge of being broken. My admiration for him is the most intense when I watch him perform in times of unspeakable tension. There is a nobility in the way that he calmly fought back against an overpowering opponent who, for the moment at least, might have gained the favor of the crowd. In the 1987 Australian Open final against local favorite Pat Cash, a weary – perhaps even spent – young Stefan, defending his title, refused to relent when his early two-set lead dwindled to nothing in the Australian heat, amid a stadium full of openly biased crowd who cheered at Stefan’s every double fault. The world first took note of Stefan's indomitable spirit in his 1988 Wimbledon Semifinal. Against Miroslav ("Big Cat") Mecir, the Czechoslovakian player known for his prowess against Swedish opponents on the tennis court, Stefan played brilliant tennis to overcome a 2-set deficit and the constant pressure of Mecir's deadly returns. The 1990 Wimbledon final against Boris Becker saw a similar drama where a top-spin lob launched by a nearly desperate Stefan salvaged a squandered early two-set lead and a losing fifth set.

|

In his 1992 US Open epic battles against Richard Krajicek, Ivan Lendl, Michael Chang, and Pete Sampras (in succession), his steely determination and clutch play pulled him back from the brink of defeat time after time. In the Chang match, especially, his resilience was almost unthinkable. In the last game of the last set of that exasperating five-setter, when he finally overcame a break to serve for the match at 5-4, Stefan faced break point at 30-40 after double faulting for the eighteenth time in that legendary battle. The American crowd was pro-Chang, and roared with glee when Stefan’s first serve was called out. Mary Carillo commented: “Oh man, that can’t be a good feeling.” Said Tony Trabert: “Eighteen double-faults later, this is a tough second serve.” The camera drew close on Stefan. His expression gave nothing away. He placidly waited till the crowd had quieted down, then flawlessly executed his favorite move: serve out wide. When the expected return came high over the net, Stefan had advanced to the net and calmly struck the ball to a well-chosen spot inside of the court, beyond the grasp of the ever-persistent Chang. “That was a dandy,” exclaimed a third commentator, with whom Trabert readily agreed. Then came the match point, and there was much speculation on what Stefan should do. Trabert advised another wide-out to the backhand. Carillo joked that an ace would be nice. At the baseline, Stefan did his usual dance to wait for the crowd to settle. As he did so often at match point, he fired a serve right down the middle, on the line. He then wisely refrained from striking on Chang’s frenzied return. Stefan turned to see the ball land inches from the side line before raising his arms and flashing that famous grin to the cheers of a stadium full of audience.

In his waning days, such moments were rare. One of the last such treats occured at the 1993 French Open, against Aaron Krickstein, an American player well know for five-set turnarounds in grand slam matches, to which Stefan had fallen victim a few times. Once again, Stefan had cruised through the first two sets, only to waver in the face of a surging Krickstein, who won the third set and was serving for the fourth. With the score at 5-3, Aaron fired three aces in a row, rousing the crowd to a frenzy. But in the set point, Krickstein’s first serve faltered. Against his second serve, Stefan unreeled an uncharacteristic drop shot from the baseline, which his startled opponent could not reach in time. From that point on Stefan lost very few points, ending up winning the match in four sets.

|

I did not get to see Stefan’s last match against Thomas Muster, the French Open champion. It was a battle fought in Vienna in the last months of Stefan’s career, and I could only imagine the sheer will which allowed Stefan to ward off the challenge of the firely Austrian - on Muster’s home turf – in a titantic struggle (6-4 6-7 7-5) to maintain an astounding head-to-head record of 10-0. (The two were to have one last encounter, in Paris, subsequently. The match ended when Muster retired after losing the first set at 2-6.)

Adding to Edberg’s allure is a touch of class – a U.S. slang for elegance and fineness. He has been aptly called the “prince of tennis.” The elegance of his game is what caught my eyes: never had I seen tennis played with such "liquid grace," to borrow a phrase from Mary Carillo. But it's more than his play. You would not catch Stefan spiting on the court, as a Becker or a Agassi might. When Stefan argued about a point – and he was no pushover when he believed that he had been wronged – it was with a determined glare down to the spot or, in his most demonstrative, with what Mary Carillo called a “whisperful of complaint.” He was always soft-spoken and ever polite. At the end of his record-breaking five-set semifinal in the 1992 US Open, when he was on the verge of physical collapse after battling for five and a half hours, he summoned his courtesy to field an on-court interview for the TV network. Stefan was always well-groomed, outfitted with tasteful tennis gears. He was loyal to his coach, Tony Pickard, who was equally loyal to him. Even after they parted their long association in 1994, Edberg told the press that Pickard would “call him every other week. He has this satellite dish at home and he would call me if he saw me play a bad match.” His peers respected Edberg – Becker said that when he played against Stefan, there was no hate; and Stefan was a good friend of Petr Korda. With Annette, his presence lent a touch of glamour to the tennis events, for which I believe he was greatly favored by tournament organizers. Stefan was known to yield a point to an opponent angered by a bad call. I saw him do this (on TV) in his last match against Chang in Roland Garros, clearing away the mark in the red clay with the sole of his shoe afterwards. Edberg was repeatedly voted the ATP’s sportsman of the year, and now the award is named after him.

|

In the U.S., Edberg was frequently maligned as “boring”. Because of his placid demeanor, he was portrayed as a bland, emotionless, robotic player by those who would not make the effort of seeing the drama beyond the surface. His victories at the US Open erased some of that stigma. But I often thought that Stefan got that bad rap from the US media because of its collective desire to tout the US stars, the prevalent ones then were the flamboyant likes of Jimmy Connors, John McEnroe and Andre Agassi – the media darlings in this country. Between Edberg and Becker, the US media preferred the more animated and vocal Becker. However, I always thought that Stefan was extremely smart in maintaining a distance from the public. In spite of his fame and fortune, he wanted to lead a normal life off the court, and he succeeded by not attracting attention to himself. In one broadcast a TV commentator mentioned that he saw Stefan walking on a busy street in London without being disturbed. In 1994, I saw him walk through the crowd on the tournament ground at Indian Wells, without any surrounding entourage. I submit that it is harder for someone in Edberg’s position to behave normally than to succumb to the glare of the spotlights and the trappings of a celebrity. I found it endearing that Edberg would tolerate interview after interview and yet seldom said anything revealing. On one occasion, when asked about his imminent retirement during the nadir of his career, he said something like, “Well, I may be, or I may be not.” Or, when, at the end of that drenching five-set US Open semifinal, asked by that uncouth TV man about whether he will watch the other ensuing semifinal between Sampras and Courier, he wearily but politely answered “maybe, we will see.”

And boring is not the word to describe a man who chose to play serve-and-volley, in defiance of the Swedish tradition of base-line tennis. (As Bud Collins put it: Stefan did not worship at the Church of Borg.) He also developed his beautiful single-handed backhand after his two-handed backhand saw him through the success of winning his European Junior Championship. Then he chose a British coach, and, with money at his disposal, opted to live in the gloom of London instead of the favorite sunny haven for tax-evading tennis stars: Monte Carlos.

In the end, though, Stefan was embraced by the tennis community of this country. I remember one commentator saying that Edberg is seen so often on our television that some might think he’s American. He was, and still is, affectionately nicknamed "Eddie." His year-long farewell in 1996 was well received. Fred Stolle, commenting on ESPN, said that “tennis will miss this man.” I was in Los Angeles at his last appearance there, where he was given a brief but heart-felt send-off in front of a full crowd; Stefan was presented with a surf-board engraved with his name. At his last US Open, Stefan was given the star treatment even though he was unseeded – his matches were played on the glamour courts and two of them in the evening. The newspapers gave him plenty of print, and the TV stations paid tribute to him by airing highlights of his career and his interviews.

I was numb with disappointments when Edberg walked off the courts of Flushing Meadows for the last time: I had ached for him to go out with a bang, proudly hoisting a trophy and flashing his winsome smile one more time -- FOR ME. When, at the end of that year, I saw clips and photos of Stefan in Stockholm sitting in that rocking chair that the Swedes bring out for their retiring tennis stars, I was in tears.

So it was that it had taken more than four years for the melancholy to dissipate, enough so that I can think of Stefan again. When I visited Manhattan this summer, I yearned for the sight of Edberg, resplendent in the glow of the summer sun on the green asphalt of the US Tennis Center. I imagined what it would be like had I been in the stands during those unforgettable matches in 1991 and 1992.

|

By doing some intensive research this past week, I discovered tidbits of news items of Stefan’s life since his retirement. All seems to be well. As with everything else, Edberg now has a perfect family: a beautiful wife and the ideal combination of children (a girl and a boy), to whom he apparently devotes his attention. He is active in tennis-related events, including the organization of the Stockholm Open. He has been present at all Davis Cup matches played in Sweden, but continues to say that he's not interested in the job as coach of the Swedish Davis Cup team – at least for the time being. Quote (from an article posted on news.com.au, 7/23/00): "If they asked me today,the answer would be no. Of course that could change in five years – but it's what I said five years ago." In January of 2000 he picked up the racket and played in an exhibition against the other two Swedish greats, Borg and Wilander, with the Swedish royalty and Coach Pickard in the audience. He is said to maintain a residence in his beloved London, and supposedly played closely against Tim Henman before this year’s Wimbledon. In an interview at this year's Stockholm Open, Stefan said he plays tennis twice a week and an occasional game of squash. A recent photo (below), presumably taken at the Stockholm Open, shows a healthy, cheerful Stefan.

|

On the web I found announcements of sports-business events that named Stefan among its presenters, events that were held in resorts and health clubs. Unlike some other tennis super stars, Stefan has not run into the usual troubles with women, money, tax, or substance abuse after his retirement. Stefan has the sense of a businessman – he even used terms such as “a good day at the office” to describe his matches, and I recall how, at the trophy presentation of the 91 US Open, Tony Trabert had to wrestle the $400,000 USD check away from a beaming Edberg so that he would focus on the ceremony.

And so I think Stefan will especially appreciate this tribute paid him. In the May 19, 2000 edition of the Helsingin Sanomat, International Edition(http://www.helsinki-hs.net/thisweek/19052000.html), in an interview of Jorma Ollila, Chairman and CEO of Nokia, the Norwegian communication equipment giant, this was written:

There seems to be mounting pressure for Stefan to grace the Champions (Senior) Tour. Interestingly, Edberg is the one player named by the current tour stars, including McEnroe, Borg, and Wilander, almost accusingly, as one who should play for the tour, as if it’s his duty to help out. Not Ivan Lendl, mind you, and not Becker (Boris is "clearly someone who is incapable of consistency," said an exasperated John McEnroe.) McEnroe was particularly belligerent, chastising Stefan for “hiding in Sweden.” In an interview by Richard Pagliaro published in Tennis Week on 12/6/2001, McEnroe reportedly said: “From conversations I have had with Edberg, my understanding is that he is still practicing, still hitting the ball. Now my point is if you are still doing that then why not get paid for doing it out here at the Albert Hall?” I salute Stefan – and it brought a smile to my face – when I read the typical Edbergian answers Stefan gave in an interview (translated from Swedish) at the Stockholm Open in October 2001:

Since his retirement, Stefan apparently has seldom set foot in the U.S. – the last time may have been when he was honored with other ex-champions at the 1997 US Open. He is may be the next one up for the Tennis Hall of Fame, and, if so, perhaps we will catch a glimpse of him, now nearing thirty-six? I am not holding out any great hope, however. I will content myself with living in the past from time to time, indulging myself with watching another match of Stefan's that leaves me on the edge of my seat.

All good things must come to an end. I consider myself fortunate to have discovered Edberg, albeit late in the game. He has no idea of the colors that he has added to my life.

Comments on this article are welcome. Please write to me at matt_rap@hotmail.com.)

You can read about a 10/2001 interview of Stefan at the web site http://www.oocities.org/edhead01us.

You can write and make donations to Stefan's Foundation in Sweden:

Stefan Edberg Foundation

c/o Swedish Tennis Association

PO Box 27915

115 94 Stockholm

Sweden