|

|

|

Website

|

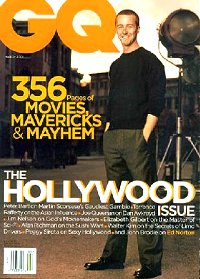

| GQ |

| March 2001 |

"Edward

had inhabited that character to the point where you didn't see any seams.

He never revealed an actor at work." To Norton, vanishing into the role

of Man 1 was the moment he understood the power of what he calls "the seduction

and hammering of and audience." It was a new found lesson that would prove

vital the following spring, when he auditioned for the part of Aaron Stampler

in Primal Fear - a role that would catapult him in the space of a year

from cranking Nirvana in a rent-controlled apartment to gracing the red

carpet at the Academy Award in the arm of Kurt Cobain's widow. The Edward

Norton who rode up the elevator in New York's Gulf & Western Building

on a spring afternoon in 1995 to audition for the role of Aaron Stampler

bore little resemblance to the aspiring sophisticate who had come to New

York from New Haven several years before. This Norton greeted Deborah Aquila,

Paramount Pictures' head of feature-film casting, with a stutter and a

thick Appalachian accent gleaned from repeated viewing of Coal Miner's

Daughter, At that point, Aquila had failed to find an actor capable of

portraying a cold-blooded killer who hoodwinks his way off death row by

pretending to have multiple-personality disorder. Most actors - including

Matt Damon - could nail one personality, but not both. "When Edward

spoke to me as Aaron, " remembers Aquila, "I could not help but fall in

love with that sincerity and that earnestness. But then he changed, and

there was a moment when I didn't think I was going to get out of that room

alive. At one point, when he was screaming in my face, he yanked me back

by my hair. Then I looked up into this kid's eyes, and I didn't recognize

him, and that genuinely scared me. I didn't know him, you know? And I thought,

Oh, great, the real thing. I hope my husband can raise our daughter by

himself." Paramount Pictures subsequently dropped the ruse of being raised

in a James Dickey novel and landed the role. Within weeks, tapes of his

screen test opposite Richard Gere and Laura Linney circulated samizdat

as producers, agents and studio executives scrambled to get a glimpse if

the phenom. "By the time we were finished shooting," says Primal Fear producer

and industry veteran Howard "Hawk" Koch Jr., "he already had met with Milos

Forman, with Woody Allen and with Anthony Mingella. He became an instantaneous

hot kid." The movie came out in April 1996, and for his debut performance

Norton grabbed an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Although

Hollywood's first impression of Norton came from Aaron Stampler - someone

so cunning, so manipulative he can fool even his own defense attorney -

my first recollection of him is singing "I'm Through With Love" as he moons

over Drew Barrymore in the 1996 Woody Allen musical Everyone Says I Love

You. And the more I talked to Norton's friends, colleagues and coworkers,

the more I wondered which Norton variation was closer to who he really

is. Is he the goofy intellectual who dedicated his first directing effort

to his late mother? Or the pretentious monster who pushes his directors

to the breaking ere? "There's the part of Edward that taught himself Japanese

at 16. But there's the part of Edward that tells you he taught himself

Japanese at 16" is how a colleague describes the thin line Norton treads

between brilliance and arrogance. On-screen and off, however, Norton, who

arrived in town with as serious a persona as "Don't Touch My Stuff"

Francis from Stripes, seems to be lightening up. He is spending the winter

filming Death to Smoochy, a dark comedy in which he plays the title role,

an innocent kiddie-TV-show performer who replaces Rainbow Randolph Smiley

(Robin Williams) and is targeted for destruction by his downwardly-spiraling

predecessor. In his personal life, too, Norton's showing signs of brightness.

Sure, he still will not pose for pictures when fans approach him on the

street, but he seems to smile more in public these days, especially when

he's courtside at Lakers games with his girlfriend of the past year, Salma

Hayek. As I wait at the gate to Los Angeles's Runyon Canyon one afternoon

a few weeks before Christmas, I wonder which face of Edward will greet

me. The park is the sort of place in which an Albee character would feel

at home. Musicians, tattooed rent boys and other creatures of the night

troll the trailhead while the rest if the world is at work. Thankfully,

I'm not waiting long before Norton pulls up in a spanking-new silver BMW

X5. (Note to paparazzi: The SUV is a rental that he'll be ditching soon.)

He's dressed in Puma shorts, hiking boots, a polo shirt and a Panavision

baseball cap. "Edward

had inhabited that character to the point where you didn't see any seams.

He never revealed an actor at work." To Norton, vanishing into the role

of Man 1 was the moment he understood the power of what he calls "the seduction

and hammering of and audience." It was a new found lesson that would prove

vital the following spring, when he auditioned for the part of Aaron Stampler

in Primal Fear - a role that would catapult him in the space of a year

from cranking Nirvana in a rent-controlled apartment to gracing the red

carpet at the Academy Award in the arm of Kurt Cobain's widow. The Edward

Norton who rode up the elevator in New York's Gulf & Western Building

on a spring afternoon in 1995 to audition for the role of Aaron Stampler

bore little resemblance to the aspiring sophisticate who had come to New

York from New Haven several years before. This Norton greeted Deborah Aquila,

Paramount Pictures' head of feature-film casting, with a stutter and a

thick Appalachian accent gleaned from repeated viewing of Coal Miner's

Daughter, At that point, Aquila had failed to find an actor capable of

portraying a cold-blooded killer who hoodwinks his way off death row by

pretending to have multiple-personality disorder. Most actors - including

Matt Damon - could nail one personality, but not both. "When Edward

spoke to me as Aaron, " remembers Aquila, "I could not help but fall in

love with that sincerity and that earnestness. But then he changed, and

there was a moment when I didn't think I was going to get out of that room

alive. At one point, when he was screaming in my face, he yanked me back

by my hair. Then I looked up into this kid's eyes, and I didn't recognize

him, and that genuinely scared me. I didn't know him, you know? And I thought,

Oh, great, the real thing. I hope my husband can raise our daughter by

himself." Paramount Pictures subsequently dropped the ruse of being raised

in a James Dickey novel and landed the role. Within weeks, tapes of his

screen test opposite Richard Gere and Laura Linney circulated samizdat

as producers, agents and studio executives scrambled to get a glimpse if

the phenom. "By the time we were finished shooting," says Primal Fear producer

and industry veteran Howard "Hawk" Koch Jr., "he already had met with Milos

Forman, with Woody Allen and with Anthony Mingella. He became an instantaneous

hot kid." The movie came out in April 1996, and for his debut performance

Norton grabbed an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Although

Hollywood's first impression of Norton came from Aaron Stampler - someone

so cunning, so manipulative he can fool even his own defense attorney -

my first recollection of him is singing "I'm Through With Love" as he moons

over Drew Barrymore in the 1996 Woody Allen musical Everyone Says I Love

You. And the more I talked to Norton's friends, colleagues and coworkers,

the more I wondered which Norton variation was closer to who he really

is. Is he the goofy intellectual who dedicated his first directing effort

to his late mother? Or the pretentious monster who pushes his directors

to the breaking ere? "There's the part of Edward that taught himself Japanese

at 16. But there's the part of Edward that tells you he taught himself

Japanese at 16" is how a colleague describes the thin line Norton treads

between brilliance and arrogance. On-screen and off, however, Norton, who

arrived in town with as serious a persona as "Don't Touch My Stuff"

Francis from Stripes, seems to be lightening up. He is spending the winter

filming Death to Smoochy, a dark comedy in which he plays the title role,

an innocent kiddie-TV-show performer who replaces Rainbow Randolph Smiley

(Robin Williams) and is targeted for destruction by his downwardly-spiraling

predecessor. In his personal life, too, Norton's showing signs of brightness.

Sure, he still will not pose for pictures when fans approach him on the

street, but he seems to smile more in public these days, especially when

he's courtside at Lakers games with his girlfriend of the past year, Salma

Hayek. As I wait at the gate to Los Angeles's Runyon Canyon one afternoon

a few weeks before Christmas, I wonder which face of Edward will greet

me. The park is the sort of place in which an Albee character would feel

at home. Musicians, tattooed rent boys and other creatures of the night

troll the trailhead while the rest if the world is at work. Thankfully,

I'm not waiting long before Norton pulls up in a spanking-new silver BMW

X5. (Note to paparazzi: The SUV is a rental that he'll be ditching soon.)

He's dressed in Puma shorts, hiking boots, a polo shirt and a Panavision

baseball cap.  His

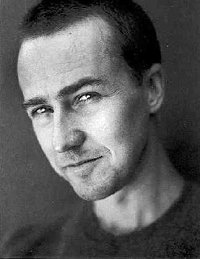

eyes are a deep blue, his face is covered with stubble, and his voice is

soft to the point of being hard to hear. During the first leg of our hike

into the Hollywood Hills, he chats amiably about a five-month traveling

binge he's just finished with family members. He is the eldest of three,

and nothing feels better to him that spending time blood on blood. In the

fall, he climbed Mount Kilimanjaro with his brother Jim (a white-water

rafting guide) and his baby sister, Molly (who works as the Africa manager

for a travel firm). He also spent a month in China visiting his father,

who works for the Nature Conservancy in Kunming, a city about one hundred

miles north of China's borders with Laos and Vietnam. Norton credits much

of the man he has become to the freewheeling intellectual discussions around

the family dinner table, as well as to the close relationship he had with

his late maternal grandfather, James Rouse, who was a real-estate developer.

As our walk reaches a scenic overlook if the architectural miasma that

extends from the Pacific Ocean to the skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles,

Norton tells me about growing up in Columbia, Maryland, a progressive community

Rouse developed. Rouse, who "invented" the shopping mall and then devoted

himself to revitalizing America's inner cities, built Columbia in the late

'60s on 14,000 acres of farmland outside Baltimore as an antidote to the

uniform sprawl he saw devouring the landscape. By the '80s, it had become

a model of a successfully integrated community. But when I ask Norton whether

he felt a sense of noblesse oblige growing up there, he brushes off the

notion that his family was the Magnificent Ambersons in a United-Colors-of-Benetton

wonderland. He claims his buddies at the local public high school had no

idea of his pedigree. He pauses. "People presume

- based on very limited information theyy've bothered to find out about

my grandfather - that I grew up in an affluent setting." Norton

then points out that when he was a kid, his father was a federal prosecutor

in the Carter Administration and later a nonprofit-environmental attorney.

His mother was a public-school teacher. "They probably,

combined, never made more than $120,000 a year [in present dollar value].

My grandfather was not a throw-money-around millionaire. He gave - in his

life and upon his death - most everything he ever made to charity."

(According to court records. Rouse left behind an estate valued at $21

million, of which $6.3 million was willed to charities after his death

in April 1996.) "Did you have a trust fund?" I ask. "No,

never," he responds. By all accounts, Norton's years in Columbia

were fairly normal. Indeed, his advanced-placement-English teacher, Andrea

Almand, tells me later that Norton distinguished himself less by his lineage

and more by his droll sense of humor - exhibited in a play he wrote and

conned his friends into performing during the annual Literary Festival.

The play was called Classroom: An Original Absurdist Play in One Scene

(With Apologies to Beckett). Sample dialogue included a character called

Student 1 announcing, "Listen, you come into this class in your animal

skins, and you leave the same. Are you truly a new man at the end of the

day? The rabbit dies, and there's nothing to be done." Yet the years in

progressive Columbia have left their mark. For when Norton and I talk about

what kind of car he wants to get, he asks my opinion of those electric-gas

hybrids, which to me are the automotive equivalent of being a vegan. And

if there is a subject about which Norton will gladly play Rouse's scion,

it is the "malling" of America - the notion that homogeneity is suffocating

eclecticism at every turn. As we take a breather atop a ridge near the

Hollywood sign, I ask how he views the fact that Starbucks and other chains

have snuffed out the independent retailers that were part of his grandfather's

initial vision for his developments at Boston's Faneuil Hall and New York's

South Street Seaport. "I look on it very negatively,"

says Norton. "And my response to that was Fight Club.

I think my grandfather would have loved Fight Club, actually, because it

spoke to the same things he was railing against for years: the franchising

of America, the creation of sameness everywhere, all our transactions taking

place within these places that are totally indistinct." To hear

him talk about the movie, it's clear that its critical (and commercial)

failure is the wound that has not healed in an otherwise charmed body of

work. A tale of Lost Boys who revolt against consumerism, the movie seemed

destined to become the third panel in a premillennial triptych of Salaryman

Angst (alongside In the Company of Men and American Beauty). But it made

less than $40 million in domestic box-office sales and suffered mixed reviews.

Sounding almost Ahab-like, Norton tells me Fight Club will eventually be

remembered like other shock-of-the-new movies such as Bonnie and Clyde

and Taxi Driver. They were initially dismissed and subsequently embraced

as classics. In Norton's still angry mind, Fight Club was done in by the

"knee-jerk cynicism" of baby-boomer critics who reuse to release their

wizened grip on the pop-culture joystick. David Denby, he says, was endemic

of the problem when he wrote in the New Yorker, "The florid anti-consumerism

rant gets overtaken by the movie's unacknowledged sadomasochistic and homoerotic

subtext. The danger of Ikea get forgotten (and why pick on Ikea, anyway?)."

"This is exactly what we're indicting in this movie,"

responds Norton, his voice rising to a crescendo; he cannot fathom

how anyone who calls himself a man could defend the soulless Scandinavian-furniture

store. As he speaks, I can picture him breaking an imitation Philipe Starck

end table over Denby's head. Needless to say, Christmas shopping with Norton

will not be a trip to the Century City mall. After finishing our hike -

in which topic ranged from Norton's plans to adapting the novel Motherless

Brooklyn for the screening to his interest in akido - we pile into the

X5 and make our way to a tiny photo gallery in Echo Park. As we head onto

the 101 freeway, the downtown skyline is bathed in that soft, sad glow

of late-afternoon twilight. After a while the conversation turns to how

his first brush with success coincided with this mother developing brain

cancer and subsequently dying in 1997. I offer my condolences and mention

how as a teenager I lost my mother to breast cancer. Curious to know whether

he, too, feels that the mother-son conversation continues beyond the grace,

I ask him if he wrestles with questions like Would my mother be proud of

me? What would she think of the choices I've made in my life? "My

family has always been so supportive of my interests. Whenever you lose

somebody, everything you do afterward is colored by that. There's loss

for sure, absences, but prior to this experience I thought of death as

an annihilation, and it's not. You think there's going to be this absolute

absence, and there isn't," he says. I nod and mention a favorite

Emily Dickenson poem that begins "Mama never forgets her birds / Though

in another tree / She looks down just as often / And just as tenderly..."

"Yeah, the conversation continues," Norton

says. His

eyes are a deep blue, his face is covered with stubble, and his voice is

soft to the point of being hard to hear. During the first leg of our hike

into the Hollywood Hills, he chats amiably about a five-month traveling

binge he's just finished with family members. He is the eldest of three,

and nothing feels better to him that spending time blood on blood. In the

fall, he climbed Mount Kilimanjaro with his brother Jim (a white-water

rafting guide) and his baby sister, Molly (who works as the Africa manager

for a travel firm). He also spent a month in China visiting his father,

who works for the Nature Conservancy in Kunming, a city about one hundred

miles north of China's borders with Laos and Vietnam. Norton credits much

of the man he has become to the freewheeling intellectual discussions around

the family dinner table, as well as to the close relationship he had with

his late maternal grandfather, James Rouse, who was a real-estate developer.

As our walk reaches a scenic overlook if the architectural miasma that

extends from the Pacific Ocean to the skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles,

Norton tells me about growing up in Columbia, Maryland, a progressive community

Rouse developed. Rouse, who "invented" the shopping mall and then devoted

himself to revitalizing America's inner cities, built Columbia in the late

'60s on 14,000 acres of farmland outside Baltimore as an antidote to the

uniform sprawl he saw devouring the landscape. By the '80s, it had become

a model of a successfully integrated community. But when I ask Norton whether

he felt a sense of noblesse oblige growing up there, he brushes off the

notion that his family was the Magnificent Ambersons in a United-Colors-of-Benetton

wonderland. He claims his buddies at the local public high school had no

idea of his pedigree. He pauses. "People presume

- based on very limited information theyy've bothered to find out about

my grandfather - that I grew up in an affluent setting." Norton

then points out that when he was a kid, his father was a federal prosecutor

in the Carter Administration and later a nonprofit-environmental attorney.

His mother was a public-school teacher. "They probably,

combined, never made more than $120,000 a year [in present dollar value].

My grandfather was not a throw-money-around millionaire. He gave - in his

life and upon his death - most everything he ever made to charity."

(According to court records. Rouse left behind an estate valued at $21

million, of which $6.3 million was willed to charities after his death

in April 1996.) "Did you have a trust fund?" I ask. "No,

never," he responds. By all accounts, Norton's years in Columbia

were fairly normal. Indeed, his advanced-placement-English teacher, Andrea

Almand, tells me later that Norton distinguished himself less by his lineage

and more by his droll sense of humor - exhibited in a play he wrote and

conned his friends into performing during the annual Literary Festival.

The play was called Classroom: An Original Absurdist Play in One Scene

(With Apologies to Beckett). Sample dialogue included a character called

Student 1 announcing, "Listen, you come into this class in your animal

skins, and you leave the same. Are you truly a new man at the end of the

day? The rabbit dies, and there's nothing to be done." Yet the years in

progressive Columbia have left their mark. For when Norton and I talk about

what kind of car he wants to get, he asks my opinion of those electric-gas

hybrids, which to me are the automotive equivalent of being a vegan. And

if there is a subject about which Norton will gladly play Rouse's scion,

it is the "malling" of America - the notion that homogeneity is suffocating

eclecticism at every turn. As we take a breather atop a ridge near the

Hollywood sign, I ask how he views the fact that Starbucks and other chains

have snuffed out the independent retailers that were part of his grandfather's

initial vision for his developments at Boston's Faneuil Hall and New York's

South Street Seaport. "I look on it very negatively,"

says Norton. "And my response to that was Fight Club.

I think my grandfather would have loved Fight Club, actually, because it

spoke to the same things he was railing against for years: the franchising

of America, the creation of sameness everywhere, all our transactions taking

place within these places that are totally indistinct." To hear

him talk about the movie, it's clear that its critical (and commercial)

failure is the wound that has not healed in an otherwise charmed body of

work. A tale of Lost Boys who revolt against consumerism, the movie seemed

destined to become the third panel in a premillennial triptych of Salaryman

Angst (alongside In the Company of Men and American Beauty). But it made

less than $40 million in domestic box-office sales and suffered mixed reviews.

Sounding almost Ahab-like, Norton tells me Fight Club will eventually be

remembered like other shock-of-the-new movies such as Bonnie and Clyde

and Taxi Driver. They were initially dismissed and subsequently embraced

as classics. In Norton's still angry mind, Fight Club was done in by the

"knee-jerk cynicism" of baby-boomer critics who reuse to release their

wizened grip on the pop-culture joystick. David Denby, he says, was endemic

of the problem when he wrote in the New Yorker, "The florid anti-consumerism

rant gets overtaken by the movie's unacknowledged sadomasochistic and homoerotic

subtext. The danger of Ikea get forgotten (and why pick on Ikea, anyway?)."

"This is exactly what we're indicting in this movie,"

responds Norton, his voice rising to a crescendo; he cannot fathom

how anyone who calls himself a man could defend the soulless Scandinavian-furniture

store. As he speaks, I can picture him breaking an imitation Philipe Starck

end table over Denby's head. Needless to say, Christmas shopping with Norton

will not be a trip to the Century City mall. After finishing our hike -

in which topic ranged from Norton's plans to adapting the novel Motherless

Brooklyn for the screening to his interest in akido - we pile into the

X5 and make our way to a tiny photo gallery in Echo Park. As we head onto

the 101 freeway, the downtown skyline is bathed in that soft, sad glow

of late-afternoon twilight. After a while the conversation turns to how

his first brush with success coincided with this mother developing brain

cancer and subsequently dying in 1997. I offer my condolences and mention

how as a teenager I lost my mother to breast cancer. Curious to know whether

he, too, feels that the mother-son conversation continues beyond the grace,

I ask him if he wrestles with questions like Would my mother be proud of

me? What would she think of the choices I've made in my life? "My

family has always been so supportive of my interests. Whenever you lose

somebody, everything you do afterward is colored by that. There's loss

for sure, absences, but prior to this experience I thought of death as

an annihilation, and it's not. You think there's going to be this absolute

absence, and there isn't," he says. I nod and mention a favorite

Emily Dickenson poem that begins "Mama never forgets her birds / Though

in another tree / She looks down just as often / And just as tenderly..."

"Yeah, the conversation continues," Norton

says.  "You

retain the connection. You look to these people in everything you're doing.

You draw inspiration from them; you still end up sharing things,"

he adds, cementing this brief moment of mutual vulnerability that plays

out against the backdrop of rush-hour traffic. In order to spend more time

with his dying mother, Norton was one of the few actors of his generation

who didn't go off to war in 1997 - he passed on the opportunity to work

with Steven Spielberg in Saving Private Ryan and Terrence Malick in The

Thin Red Line. The following year, he dedicated his directorial debut,

Keeping the Faith, to Robin Norton, because his interest in making it had

to with his mother's fondness for romantic comedies as it did with producing,

directing and starring in something he cowrote with his best friend. As

an illustration of the "conversation continuing," he adds that as a kid

he would often watch a movie and then break it down by genre with his English-teacher

mom, so "a lifetime of discussions with her informed doing that movie."

Talking about the genre of romantic comedy with Norton, it's easy to see

how he could never be satisfied simply being an actor for hire. His literary

sensibility crops up as we talk about how tough it is to figure out new

obstacles to keep the hero and heroine apart now that we live in a supposedly

classless society (and Woody Allen has all but exhausted neuroses as barriers

to true love). So when his pal Stuart Blumberg pitched him the premise

of a priest and a rabbi falling in love with the same girl - a movie equal

parts The Philadelphia Story and Bridget Loves Bernie - Norton liked the

idea of religion as the obstacle. Part of the allure in working with Blumberg,

he says, was collaborating with a guy he had shared his first apartment

with in New York, a guy with whom he's been a loser - eating pizza and

watching Withnail & I over and over. From their tiny brownstone apartment

on West 78th Street, Norton and Blumberg conspired to break into the big

time: writing spec episodes for TV shows, penning a Naked Gun-esque comedy

about an inept superhero called Stupid Man. And the two Yalies were poised

to write what they were sure was going to be their golden ticket into the

Dream Factory - a spec script about Mata Hari - when Norton auditioned

for the Primal Fear role. Says Blumberg when we chat on the phone about

how quickly went from geek to gorgeous: "Just to show you how naive I was

when he got the part, I remember saying, 'OK, we're still going to write

Mata Hari?' And he's like, 'Sure.' So it didn't really sink in until he

got the Woody Allen movie and we went to Michael's Pub during the shoot

and he introduced me to Woody, who was playing there with his band." As

fond as Blumberg is of his writing partner, he has heard about the actor's

reputation for being difficult. "It's a function of being unable to hold

back when he sees something that could be working at a different, higher

level," he says, trying to put the behavior in context. There is always

a point in an interview where you have to ask the deal breaker, the question

that send the star out of the room or into an unintelligible rant peppered

with pithy words life craft, misunderstood and bogus. And with Norton,

that question would be Does being the actor's actor of your generation

mean you get to be the asshole's asshole as well? So before addressing

the "Are you difficult?" question with Norton, I wait until the BMW is

safely parked. "So how would you respond to the notion that you're an overreached?"

I ask, figuring this will put a quick end to my Sony microcassette recorder.

"Someone who has a hard time respecting the boundaries between actor and

director, actor and screenwriter, actor and producer?" It's dark enough

now for Norton's face to be illuminated by the eerie night-vision orange

of the dashboard, and he doesn't bother to bullshit, nor does he get ticked

off. Instead, he answers the charge directly and succinctly. "I'm

incapable of engaging as an actor on something without engaging as a dramatist.

And when you work with great people, they not only accept it, they welcome

it. But when you work with insecure people, it's a problem." The

implication is perhaps to Tony Kay, the director of American History X,

a film for which Norton received an Oscar nomination for Best Actor but

a film whose director still refers to Norton as a "narcissistic asshole

person." Norton was not the TV-commercial director's first choice for the

role of Derek Vinyard, a reformed skinhead who watches rage destroy his

family. But Kaye, a first-time director, quickly came around and welcomed

Norton's contributions to David McKenna's script. "He was a brilliant guy

to work with," says Kaye, "and he would have won the Oscar for American

History X if he hadn't fucked me over in the editing process." The two

worked well together during the shoot and for most of post production.

Their collaboration went off the rails, however, after Kaye took more than

a year to edit the movie (most rookie directors get four months) and the

studio sent Norton into the editing room to work alongside (and coax a

final cut out of) Kaye. By the summer of 1998, when Norton went off to

make Fight Club, New Line Cinema decided to take the movie away from Kaye,

and the director retaliated with the Dadaist stunt of placing full-page

ads in the Hollywood trade papers, addressed to New Line executives, quoting

Albert Einstein, Abraham Lincoln and John Lennon (Everybody's hustlin'

for a buck and a dime / I'll scratch your back and you knife mine). Norton

was caught in the crossfire, with Kaye making him out to be a patrician

brat by erroneously whining to Vanity Fair, "His grandfather invented the

ice cream cone!" On Fight Club, the legend of Edward the Difficult grew

when stories made the rounds about his clashing with director David Fincher,

regarding details as small as whether his character would wear Stan Smith

or Chuck Taylor sneakers. "He's a daunting proposition because you're taking

on a collaborator," says Fincher of Norton. "You

retain the connection. You look to these people in everything you're doing.

You draw inspiration from them; you still end up sharing things,"

he adds, cementing this brief moment of mutual vulnerability that plays

out against the backdrop of rush-hour traffic. In order to spend more time

with his dying mother, Norton was one of the few actors of his generation

who didn't go off to war in 1997 - he passed on the opportunity to work

with Steven Spielberg in Saving Private Ryan and Terrence Malick in The

Thin Red Line. The following year, he dedicated his directorial debut,

Keeping the Faith, to Robin Norton, because his interest in making it had

to with his mother's fondness for romantic comedies as it did with producing,

directing and starring in something he cowrote with his best friend. As

an illustration of the "conversation continuing," he adds that as a kid

he would often watch a movie and then break it down by genre with his English-teacher

mom, so "a lifetime of discussions with her informed doing that movie."

Talking about the genre of romantic comedy with Norton, it's easy to see

how he could never be satisfied simply being an actor for hire. His literary

sensibility crops up as we talk about how tough it is to figure out new

obstacles to keep the hero and heroine apart now that we live in a supposedly

classless society (and Woody Allen has all but exhausted neuroses as barriers

to true love). So when his pal Stuart Blumberg pitched him the premise

of a priest and a rabbi falling in love with the same girl - a movie equal

parts The Philadelphia Story and Bridget Loves Bernie - Norton liked the

idea of religion as the obstacle. Part of the allure in working with Blumberg,

he says, was collaborating with a guy he had shared his first apartment

with in New York, a guy with whom he's been a loser - eating pizza and

watching Withnail & I over and over. From their tiny brownstone apartment

on West 78th Street, Norton and Blumberg conspired to break into the big

time: writing spec episodes for TV shows, penning a Naked Gun-esque comedy

about an inept superhero called Stupid Man. And the two Yalies were poised

to write what they were sure was going to be their golden ticket into the

Dream Factory - a spec script about Mata Hari - when Norton auditioned

for the Primal Fear role. Says Blumberg when we chat on the phone about

how quickly went from geek to gorgeous: "Just to show you how naive I was

when he got the part, I remember saying, 'OK, we're still going to write

Mata Hari?' And he's like, 'Sure.' So it didn't really sink in until he

got the Woody Allen movie and we went to Michael's Pub during the shoot

and he introduced me to Woody, who was playing there with his band." As

fond as Blumberg is of his writing partner, he has heard about the actor's

reputation for being difficult. "It's a function of being unable to hold

back when he sees something that could be working at a different, higher

level," he says, trying to put the behavior in context. There is always

a point in an interview where you have to ask the deal breaker, the question

that send the star out of the room or into an unintelligible rant peppered

with pithy words life craft, misunderstood and bogus. And with Norton,

that question would be Does being the actor's actor of your generation

mean you get to be the asshole's asshole as well? So before addressing

the "Are you difficult?" question with Norton, I wait until the BMW is

safely parked. "So how would you respond to the notion that you're an overreached?"

I ask, figuring this will put a quick end to my Sony microcassette recorder.

"Someone who has a hard time respecting the boundaries between actor and

director, actor and screenwriter, actor and producer?" It's dark enough

now for Norton's face to be illuminated by the eerie night-vision orange

of the dashboard, and he doesn't bother to bullshit, nor does he get ticked

off. Instead, he answers the charge directly and succinctly. "I'm

incapable of engaging as an actor on something without engaging as a dramatist.

And when you work with great people, they not only accept it, they welcome

it. But when you work with insecure people, it's a problem." The

implication is perhaps to Tony Kay, the director of American History X,

a film for which Norton received an Oscar nomination for Best Actor but

a film whose director still refers to Norton as a "narcissistic asshole

person." Norton was not the TV-commercial director's first choice for the

role of Derek Vinyard, a reformed skinhead who watches rage destroy his

family. But Kaye, a first-time director, quickly came around and welcomed

Norton's contributions to David McKenna's script. "He was a brilliant guy

to work with," says Kaye, "and he would have won the Oscar for American

History X if he hadn't fucked me over in the editing process." The two

worked well together during the shoot and for most of post production.

Their collaboration went off the rails, however, after Kaye took more than

a year to edit the movie (most rookie directors get four months) and the

studio sent Norton into the editing room to work alongside (and coax a

final cut out of) Kaye. By the summer of 1998, when Norton went off to

make Fight Club, New Line Cinema decided to take the movie away from Kaye,

and the director retaliated with the Dadaist stunt of placing full-page

ads in the Hollywood trade papers, addressed to New Line executives, quoting

Albert Einstein, Abraham Lincoln and John Lennon (Everybody's hustlin'

for a buck and a dime / I'll scratch your back and you knife mine). Norton

was caught in the crossfire, with Kaye making him out to be a patrician

brat by erroneously whining to Vanity Fair, "His grandfather invented the

ice cream cone!" On Fight Club, the legend of Edward the Difficult grew

when stories made the rounds about his clashing with director David Fincher,

regarding details as small as whether his character would wear Stan Smith

or Chuck Taylor sneakers. "He's a daunting proposition because you're taking

on a collaborator," says Fincher of Norton.  The

director and the actor ended the production as friends, though. "No one

could have played that part except for Edward. I think it's probably easy

to read him the wrong way because he's still so new and because he's somebody

to be reckoned with." As he steps out of the X5 and into the Fototeka gallery,

Norton exhibits nearly the same attention to detail in choosing a photograph

as he does in choosing a role (or a character's footwear). On the ride

over, he mentioned that he has violated his criteria (great script plus

great director) only one time since he's been able to exercise free will

over his career. And that one time is his next movie, The Score. Working

with two titans of their respective generations - Robert De Niro and Marlon

Brando - was an offer he could not refuse. "Two Corleones," I blurt out.

"You've got the matched set: Young Vito and Old Vito." "I'd

do this one for the poster," he says, sounding more like film buff

than film star until the database in my head scrolls to the more than $6

million he was paid for movie. Curious to know whether the shoot lived

up to the ex-waiter's daydreams, I ask about the first day the three bad

boys had a scene together. Norton admits to allowing himself a brief moment

to stare in awe as the camera rolled. Then, as Norton said his line, Brando

dribbled designer water down the front of his shirt. And when Norton turned

to De Niro for a reaction, he caught De Niro catnapping on his feet. In

lieu of a lengthy conversations about Stella Adler, Brando further endeared

himself to Norton through practical jokes. A favorite prank involved a

high-tech whoopee cushion that would make six different fart sounds depending

on how the Wild One manipulated the remote control. "Marlon

would always figure out where Bob was going to be sitting in a scene, and

he would hide it somewhere near him," remembers Norton. "And

he would wait until Bob got warmed up in the third or fourth take and then

start firing it off while we were trying to be cool-thief serious."

To see whether Norton was up to his old tricks on The Score. I ask whether

he was merely an actor for hire. He explains that he transformed the script

so that burglary became a metaphor for acting - with Brando's thief representing

raw talent, De Niro's character combining talent with very disciplined

career choices and Norton's character being "a young guy trying to make

his bones." Reached in the editing room, The Score's director Frank Oz,

acknowledged that while it was a contentious shoot, there was, to quote

David Selznick, only one "madman at the helm," meaning Frank Oz. He welcomed

what he describes as Norton's tremendous involvement in his character's

development and some contributions to the overall shape of the piece, but

he noted that there were many writers who worked on the script at different

stages of the game, among them Lem Dobbs (The Limey), Ebbe Roe Smith (Falling

Down) and Kario Salem (HBO's The Rat Pack). Adds the director, "Edward

didn't want to play the Tom Cruise character in The Color of Money. He

didn't want to be the smart-aleck punk who thought he knew everything.

He wanted his character to be at the same level as Bob's character professionally."

(Amateur psychiatrists, feel free to discuss this at home.) Norton may

no longer be a smart-aleck punk. As he sifts through various black-and-white

photographs that A.H. Buchman snapped in Mexico during the early '40s,

I think back to a conversation earlier in the day, when he conceded that

part of growing up for him has been coming to grips with his meddlesome

nature. He suggests that an example of this maturation process is his decision

to pass on the lead in MGM's upcoming adaptation of the World War II novel

Hart's War. After reading the script, he feared he would not be able to

act in the movie without donning his screenwriter cap and getting in people's

faces, so he walked away from the opportunity to work again with Primal

Fear director Gregory Hoblit. Instead, he chose to strap on a foam-rubber

rhino suit in Danny DeVito's next directorial outing, Death to Smoochy.

"It's a script that I wouldn't change a word of.

I can show up, be an actor and then go home at night and not obsess,"

he says. At 31, Norton is showing other signs of maturity. He talks about

Sean Penn and Warren Beatty as examples of two actor-directors who are

compass points by which he would like to chart his own career. And as the

conversation drifts from these two legendary Hollywood rogues to his romantic

life, he clams up on the grounds that it's rude to offer up the affections

of a woman for tabloid fodder. He also worries that the more the general

public knows about him, the harder it will be for him to vanish into the

roles he plays. Still, during our time together, he's been dropping more

hints about his feelings for Hayek than Hansel and Gretel had crumbs. Even

though his black book once included Courtney Love, Drew Barrymore, and

Tara Reid, he seems genuinely enamored of the woman he's dated for well

over a year. And he grows slightly animated whenever he talks about a recent

trip to Mexico, The

director and the actor ended the production as friends, though. "No one

could have played that part except for Edward. I think it's probably easy

to read him the wrong way because he's still so new and because he's somebody

to be reckoned with." As he steps out of the X5 and into the Fototeka gallery,

Norton exhibits nearly the same attention to detail in choosing a photograph

as he does in choosing a role (or a character's footwear). On the ride

over, he mentioned that he has violated his criteria (great script plus

great director) only one time since he's been able to exercise free will

over his career. And that one time is his next movie, The Score. Working

with two titans of their respective generations - Robert De Niro and Marlon

Brando - was an offer he could not refuse. "Two Corleones," I blurt out.

"You've got the matched set: Young Vito and Old Vito." "I'd

do this one for the poster," he says, sounding more like film buff

than film star until the database in my head scrolls to the more than $6

million he was paid for movie. Curious to know whether the shoot lived

up to the ex-waiter's daydreams, I ask about the first day the three bad

boys had a scene together. Norton admits to allowing himself a brief moment

to stare in awe as the camera rolled. Then, as Norton said his line, Brando

dribbled designer water down the front of his shirt. And when Norton turned

to De Niro for a reaction, he caught De Niro catnapping on his feet. In

lieu of a lengthy conversations about Stella Adler, Brando further endeared

himself to Norton through practical jokes. A favorite prank involved a

high-tech whoopee cushion that would make six different fart sounds depending

on how the Wild One manipulated the remote control. "Marlon

would always figure out where Bob was going to be sitting in a scene, and

he would hide it somewhere near him," remembers Norton. "And

he would wait until Bob got warmed up in the third or fourth take and then

start firing it off while we were trying to be cool-thief serious."

To see whether Norton was up to his old tricks on The Score. I ask whether

he was merely an actor for hire. He explains that he transformed the script

so that burglary became a metaphor for acting - with Brando's thief representing

raw talent, De Niro's character combining talent with very disciplined

career choices and Norton's character being "a young guy trying to make

his bones." Reached in the editing room, The Score's director Frank Oz,

acknowledged that while it was a contentious shoot, there was, to quote

David Selznick, only one "madman at the helm," meaning Frank Oz. He welcomed

what he describes as Norton's tremendous involvement in his character's

development and some contributions to the overall shape of the piece, but

he noted that there were many writers who worked on the script at different

stages of the game, among them Lem Dobbs (The Limey), Ebbe Roe Smith (Falling

Down) and Kario Salem (HBO's The Rat Pack). Adds the director, "Edward

didn't want to play the Tom Cruise character in The Color of Money. He

didn't want to be the smart-aleck punk who thought he knew everything.

He wanted his character to be at the same level as Bob's character professionally."

(Amateur psychiatrists, feel free to discuss this at home.) Norton may

no longer be a smart-aleck punk. As he sifts through various black-and-white

photographs that A.H. Buchman snapped in Mexico during the early '40s,

I think back to a conversation earlier in the day, when he conceded that

part of growing up for him has been coming to grips with his meddlesome

nature. He suggests that an example of this maturation process is his decision

to pass on the lead in MGM's upcoming adaptation of the World War II novel

Hart's War. After reading the script, he feared he would not be able to

act in the movie without donning his screenwriter cap and getting in people's

faces, so he walked away from the opportunity to work again with Primal

Fear director Gregory Hoblit. Instead, he chose to strap on a foam-rubber

rhino suit in Danny DeVito's next directorial outing, Death to Smoochy.

"It's a script that I wouldn't change a word of.

I can show up, be an actor and then go home at night and not obsess,"

he says. At 31, Norton is showing other signs of maturity. He talks about

Sean Penn and Warren Beatty as examples of two actor-directors who are

compass points by which he would like to chart his own career. And as the

conversation drifts from these two legendary Hollywood rogues to his romantic

life, he clams up on the grounds that it's rude to offer up the affections

of a woman for tabloid fodder. He also worries that the more the general

public knows about him, the harder it will be for him to vanish into the

roles he plays. Still, during our time together, he's been dropping more

hints about his feelings for Hayek than Hansel and Gretel had crumbs. Even

though his black book once included Courtney Love, Drew Barrymore, and

Tara Reid, he seems genuinely enamored of the woman he's dated for well

over a year. And he grows slightly animated whenever he talks about a recent

trip to Mexico,  where

he traveled around the country with Hayek. For someone who fancies himself

a New Yorker, he seems happy about spending more time in Los Angeles, presumably

to be closer to her. This winter he will do a cameo as Nelson Rockefeller

in a Frida Kahlo biopic Hayek is starring in. For that reason, perhaps,

the photograph he settles on to purchase is telling. The black-and-white

image captures Diego Rivera in the very moment that inspiration flashes

from his eyes to his brush. And I can't help but wonder if this is bound

for Norton's inamorata. If he were my buddy, this is the moment I would

churlishly blurt out, "What's the subtext here? Are you saying, 'I want

to be the Diego to your Frida?'" But I keep my greasy journalist mouth

buttoned up, electing to respect his request for privacy. Besides, the

article may end up alongside the other clippings his old high school teacher

Andrea Almand posts about Ed ("he was just Ed then") on here bulletin board

to motivate her students. And as far as her more prurient charges are concerned,

the secret to the Edward Norton mystique should already be clear. Study

hard, be good to your friends, raise hell for your artistic choices and

you too may end up courtside at the Lakers in the company of a beautiful

and talented woman. where

he traveled around the country with Hayek. For someone who fancies himself

a New Yorker, he seems happy about spending more time in Los Angeles, presumably

to be closer to her. This winter he will do a cameo as Nelson Rockefeller

in a Frida Kahlo biopic Hayek is starring in. For that reason, perhaps,

the photograph he settles on to purchase is telling. The black-and-white

image captures Diego Rivera in the very moment that inspiration flashes

from his eyes to his brush. And I can't help but wonder if this is bound

for Norton's inamorata. If he were my buddy, this is the moment I would

churlishly blurt out, "What's the subtext here? Are you saying, 'I want

to be the Diego to your Frida?'" But I keep my greasy journalist mouth

buttoned up, electing to respect his request for privacy. Besides, the

article may end up alongside the other clippings his old high school teacher

Andrea Almand posts about Ed ("he was just Ed then") on here bulletin board

to motivate her students. And as far as her more prurient charges are concerned,

the secret to the Edward Norton mystique should already be clear. Study

hard, be good to your friends, raise hell for your artistic choices and

you too may end up courtside at the Lakers in the company of a beautiful

and talented woman.

By John Brodie

|

Copyright © 2000-2001 Edward Norton Online website. All rights reserved.