NOW AND THEN

THENIn the late nineteenth century, there were seven coalmines in Atherton, three of them owned by the Fletcher Burrows Family. They were Chanters, Gibfield, and Seven Feet. The family were at that time great benefactors to the local community, and forward thinking for their time, they were the first to develop a Mines Rescue & Training Station. In between Atherton and Leigh they purpose built a small village to house their employees and it was named Howe Bridge. The village boundary began where the Fletcher Burrows built their home and named it Briarcroft Hall. It was a majestic house with tennis courts at the rear and ajoining stables. The Hall was donated in the 1920's by the family and used by the youth of the local community for recreational purposes such as tennis, table tennis and social skills. It was a great day for the village when the then Duke of York who later became King George V1 officially opened it. Opposite the Briarcroft Hall lived the local doctor and prior to the National Health Service a visit to him or indeed a home visit would be expensive. As a form of insurance to enable miners and their families pay for these services it was possible to pay by weekly installments as much as a shilling a week. It was quite common for a collector (named the doctors man) to be seen collecting the money. The Fletcher Burrows family built a number of utilities within the village, making it a self contained little community, and most things needed to keep body and soul together were easily purchased without leaving the perimeter of the village.

The village was split into two parts, disected by the main Atherton to Leigh Road. All the shops were built on the main road, and to the rear on one side was Bridge Farm owned originally by a Thomas Bridge, who was titled the farm in 1698, this supplied all the fresh milk and produce necessary for a self sufficient village. The farmer delivered the milk in the early hours of the morning, not in bottles but by filling up jugs and containers supplied by the families. Next to the farm was St. Michael and All Angels Church of England school it was built in a unique style with seven fireplaces. Each fireplace had it's own tiled motto overhead, the first fireplace is in the entrance hall, and the motto is "Manners Makyth Man". Then came the Village Club which was a drinking and social establishment. Further along were garden fronted houses which were elevated above the height of the road. In the middle of these houses was a boot, clog and shoe repairer, and in those days it was a very profitable business because all the miners and their families wore clogs. He was known locally as the clogger. Further along was a fish and chip shop, a sweet shop which also sold newspapers and two grocery shops one of them was also a bakery. Directly opposite was another elevated row of houses, known as the Promenade (prom) and in the middle was a Bathhouse which at that time was quite revolutionary. The Bathhouse was open to the public on Fridays and Saturdays but only for self hygenic purposes, not for swimming. Customers paid one old penny (in those days there were 240 pennies in a £1) for the privilege of having a luxurious bath with hot and cold running water, in a private locked cubicle. The weekday alternative was a tin bath in front of a roaring fire, or in summer in the back yard, and after a shift down the pit even that was welcome. Behind the Village Club was a row of terraced houses, overlooking a crown bowling green, hence the name Bowling Green Row. A crown bowling green has a slight hump in the middle, and is peculiar to the North of England, in contrast to a flat bowling green which is common elsewhere. Opposite the school, next to the Briarcroft Hall, (which incidentally has now been demolished due to vandal damage), was a row of terraced houses, containing three shops, a hat and glove shop, (which my Aunty Margery now lives in), a Police house and a Haberdashers selling buttons and bows. The owner of the Haberdashers doubled up as the Rent man, and when he was collecting the rent, he carried with him a hammer and nails, and if he saw any damaged fences etc. he would repair them on the spot. Any major problems would be reported to the owners, and workmen would be sent to repair such items. To the rear of these houses were several streets, Earl Street, Bridges Street, and Lilford street where three generations of my family were born. Back to back with Lilford street was Rivington Street overlooking a number of pens (allotments) these were rented out to the miners, and each pen produced its own crop of vegetables, fruit and flowers, as well as eggs and chickens. All the produce could be bought, chickens were sold, along with the proviso that the puchaser had to pluck and clean them theirselves. There were other ways of buying food and not leaving the village, for instance the fish merchant would come and sell his fish from the back of his horse and cart, a grocer and a paraffin man came, each with their horses and carts and shouting their wares. The paraffin man sold paraffin to fill the kelly lamps, which were used to stop the toilet pipes from freezing in winter, as well as candles, boot and shoe polish, cooking utensils, and ironmongery. I think the most important man to the miners was the Knocker Up, whose vital job was to act as a mobile alarm clock in the village. He carried a long pole, and for a small fee he would come in the early hours, before the first shift at the pit began, and knock on the bedroom window until someone answered his knock.

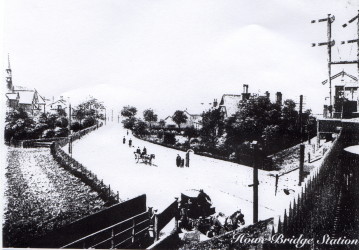

All the streets were terraced and most houses had a small garden at the front, and a small private back yard which housed the outside toilet. They where only small houses and the families tended to be large, but compared to living conditions in other areas, they were like little palaces. Every two or three years the painters and decorators employed by Fletcher Burrows came to wallpaper and paint the house interior. A choice of wallpaper was allowed, but the woodwork inside and out was always painted dark green, making the small rooms look dismal. As an incentive to keep the village looking tidy there was a yearly gardening competition, and the winner was awarded a prize. My family were not such good gardeners, so consequently they could not even say what the prize would be. The boundary of the village ended at the train station and railway bridge, and after that all the houses were privately owned. The family built in 1887 the the beautiful church of St. Michael and All Angels and it was situated a few yards under the railway bridge and just beyond the boundary. Opposite the church was another fine house owned by the Fletcher Burrows family, and this was named The Hindles, but this has subsequently been demolished. Next to The Hindles was a workyard owned by the Fletcher Burrows family, and all the parts and materials necessary for repairing the properties were stored there. The railway station was originally called Chowbent Station and it was opened in 1864 on the Eccles-Tyldesley-Wigan branch of the London and North Western Railway. Although the station was closed in 1959, the line remained in use for another decade. The bridge was totally removed after open cast mining in the area ceased in the late 1980's.

To summarize I have only covered the village as it was planned and not the people who lived their, that is a book waiting to be written, they were the heart of Howe Bridge, and what ever little they had would be shared with those who had less. Is was a noisy bustling village full of life, the sounds of the miners clogs on the cobble stones going or returning from work, and the pit whistle ending a shift. The children playing and the housewives shouting to one another as they pegged their washing out, on washing lines in the big cobble stoned backs. Steam trains steaming along the railway lines, cocks crowing and pigeons flying. I think it was a hard and earthly lifestyle and not a lot of privacy for the individual. The families were large and four sharing a bedroom was normal, in fact four sharing a bed was common, two at the top and two at the bottom. The females that worked were either Pit Brow Lasses, who worked at the pit head chipping the slate away from the coal, or they were employed in the cotton mills in Atherton. The village was almost totally male dominated and I don't think the wives had such a good deal (my opinion only). Having said that it was a very close knit community who together shared sad times as well as happy times and it was said that if you kicked one Howe Bridger, every Howe Bridger limped.

KNOCKER UP

PIT BROW LASSES

ST.MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS CHURCHNOW

ST.MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS SCHOOLWhen Howe Bridge Village was built in the 1870's to house miners employed by Fletcher Burrows, there were seven active mines in Atherton. Since the demise of the coal industry however, not only are there no longer any mines in Atherton, but neither are there any in Lancashire. Owing to this fact, the character of the village has totally changed. At one time, the only way that one could get a house in Howe Bridge was for the male member of the household to be employed in the coal mines and the female members usually worked in the local cotton mills or the nut and bolt works. By the 1950's the school leaving age was extended and young men who had previously followed their fathers down the mines had more job choices. When they got married they either lived in the local council houses, bought their own or moved away all together. The heart of the village was fragmenting. Equality arrived for the females of the village in the 1960's when the Briarcroft Hall which for half a century had been a male preserve, finally admitted girls and it became a youth club rather then a boys club. In the early 1970's the National Coal Board who had inherited the housing stock from Fletcher Burrows, renovated them and installed inside toilets and bathrooms. They managed to to this by utilizing what was previously a bedroom, making some houses only one bedroomed. The Bathhouse which at one time was of vital importance to the village, was now redundant, and was subsequently converted into a house, the Boot repairers (cloggers) was turned into a Hairdressers shop and one of the Grocers shops was transformed into a house. The uniquely designed St. Michael and All Angels school and the church of the same name still remain as does the Village Club. The Briarcroft Hall fell into disrepair, and after vandal damage it was finally demolished in the late 1990's. Bridge Farm was demolished around the early 1960's to make way for a street of privately owned Bungalows, it is named Hope Fold Avenue.

The qualification for taking possession of a house changed in the late 1970's when the National Coal Board sold the houses to the local council, and people from different job areas bagan to move into the village. At the end of the twentieth century once again the houses which are not privately owned have been modernised by Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council. This time the planners have used modern methods, for example double glazed window units but the design has tried to reflect the past as befits an architecturally listed village. There are still some families who have lived in Howe Bridge for two or three generations, and have seen a lot of change, but have their memories. Unfortunately most of tbe people who now live in the small cosy houses, with all the modern conveniences will never know the wealth of history in the village, the warmth, friendliness and complete unity of the hard working miners and their families they were built for.

click

to return to top of page

[ Sign my GuestBook ] - [ Read my GuestBook ]

[ GuestBook by TheGuestBook.com ]