The War in The West

Germany and France mobilized their armies very quickly. Most of the French were sent to the northeast part of the country while the German force, the bulk of it's army, were making their way through Belgium and towards France. Austria and Russia were slower in mobilizing.

Germany was the first to attack, and would employ The Schlieffen Plan, submitted in 1905, and attack France, through Belgium. Germany demanded that Belgium allow their troops free passage to engage The French Army, that would be destroyed defending Paris. Belgium refused. Belgian soldiers, outnumbered 10 to 1 by Germans and better equipped for a war in the last century, would stand and fight. Britain had vowed to honour Belgian neutrality and this violation, coupled with a declaration of war against France, brought Britain into the conflict. Germany occupied Luxembourg and then invaded Belgium. The Belgian resistance, in and of itself, was futile but successful in two ways. First, the extra few days it took The Germans to pass through Belgium allowed France more time to mobilize. Second, and more far reaching, was a new tool of war: propaganda. Stories of German atrocities reached England and fired the spirit of the public. Germans were a menace that had to be stopped at all cost. In 1900, German troops who took part in squashing The Boxer Rebellion in China, were told to act "like Huns". The name, among others stuck and in both world wars it was common for The British to refer to Germans as "Huns". As viscous as the attack of the German army was on Belgian civilians, it was even further exaggerated in the British press. The enemy were baby killers and less than human, making them much easier to hate and to kill. Germany was the "mad dog of Europe". Speaking of dogs, in the streets of English cities, dachshunds were kicked. During the war, the modern surname for the British monarchy was changed to "Windsor" from the very Germanic "Goethe-Saxburg".

Unleashed on Belgium was the greatest war machine the

world had ever seen. Not only men but horses in the millions were recruited on

all sides. The Germans justified the violation of Belgian neutrality with a

false claim that France was about to do the same thing.

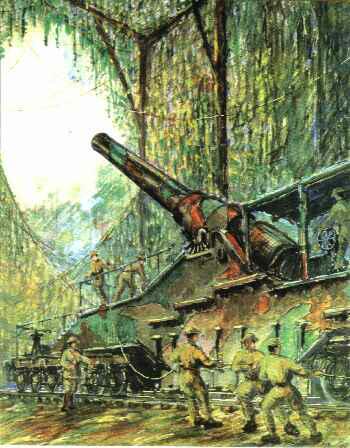

Big Bertha, the world's largest artillery gun, moved along the rails and fired shells that weighed tons. The Belgian forts which were deemed impregnable, were blasted to bits. The German command was outraged by the Belgian resistance and considered it a war crime. There were propaganda stories of German soldiers in hospital having been blinded by Belgian women and children. When the main army had marched, primarily Prussian, the occupying arm, primarily Saxons, moved in and began a campaign of terror to squash the francs-tireurs, the resistance fighters. Germany announced that 10 Belgians would be executed for each German soldier killed by civilian resistance, and they carried through with this promise. Civilians were shot including women, and children as young as 3 months old. Survivors who did not die by their gunshot wounds were bayoneted. Despite their superior numbers and superior skills, German soldiers fell in the thousands against what machine guns and other armaments the Belgians did have. The slaughter of The Great War had begun. Belgium resistance could not stop the war machine. The Belgian commander was captured, taken unconscious. "I was taken unconscious", he said. "Put that in your dispatches".

The university town of Louvain became the symbol of The Belgian Campaign. The attack began on Aug. 25th, 1914. Louvain was the home of Flemish Renaissance and Gothic art, much of it destroyed. It seemed that the triumph of Kultur would be at the expense of other cultures.

The French and British

France's Schlieffen Plan, was Plan XVII. The German gamble was that France would assume that the right wing of The German Army, moving through Belgium, was a diversion and that the real forces would be on the left striking at the heart of France. There was about a week of time between the mobilization of The French and German armies and the first battles. The French offensive began on Aug. 14th, with an attack on Sarrebourg in Lorraine. For four days the Germans, though opposing the French, fell back and the French gain was a as much as 25 miles into German territory. Chateau-Salins, Dieuze and Sarrebourg were taken by Aug. 18th. The army in Alsace took Mulhouse on the 19th. Then The German resistance began to stiffen and the French armies developed wide gaps between the armies. German heavy artillery began to inflict horrendous losses on the French and by Aug. 23rd they were in retreat. The Schlieffen plan warned against being seduced by a French weakness to attack on the left, but the temptation was too great. A German offensive began and The French, having fallen back, put up a strong defense. In fact, the left wing had been given a stronger force, at the expense of the right, than Schlieffen had called for.

French armies now moved in to

engage The German Army in Belgium. Not knowing that the left wing was no

diversion but contained the bulk of the invading force, Plan XVII was useless.

Joffre, the French commander, called for an offensive by this time joined with

The British Expitionary Force, commanded by Sir John French.

To The French, the battle was known as The Sambre; To The British, Mons.

Despite repeated offensives by Joffre's armies, it was The Germans that

advanced. As in the South, The French army was soon in retreat in The North.

The BEF consisted of four infantry and one cavalry divisions. Despite it's

size, the BEF was purely a professional army. Many soldiers had experience with

entrenchments used in The Boer War. The British armies were ordered to hold the

Mons-Conde canal, and dug themselves in. When The Germans attacked, the British

resistance was fierce and totally unexpected. The fighting left both sides

exhausted. But, because of the French losses at The Sambre, both armies were

ordered to retreat.

During the next two weeks, the allied armies would fall back all the way to the outskirts of Paris. The retreat was at such a brisk pace that soldiers would fall asleep as soon as they stopped marching. By September 3rd, The German right wing was actually sitting 40 miles east of Paris. The BEF was sitting southeast of Paris. For many historians, including Barbara Tuchman, the war was ultimately decided when The German armies pulled back thus allowing a French counter strike at The Marne. To others it is The Battle of The Marne itself which lead to the trenches and the end of the war of movement.

The Marne

On September 4th, it was 35 days after mobilization. The Schlieffen Plan called for a decisive battle in the west by the 40th day, before The Russian Army could launch an offensive. German commander Moltke (the younger) called for the left wing to stand pat while the right wing advanced. Unfortunately, this was Schlieffen turned on his head - the original goal was for exactly the opposite to happen with the left wing driving The French into the right wing.

As the German armies on the left halted, Joffre decided that it was time for an allied offensive. Unfortunately, when both French and English units encountered Germans where they were not expected to be, this set off the battle a day sooner than anticipated, on September 5th instead of the 6th. The French were now going to attempt an encirclement of The Germans.

Unlike his eventual replacement, Haigg, French could not bear casualties and it took visits from Kitchener, his commander at home, and Joffre himself to convince him to bring the BEF into the battle. Ironically French could speak very little French. The BEF had fallen too far back to join the main offensive, and The French were beaten back badly with each thrust forward. This is when every available French soldier was rushed to the front and involved the use of taxi cabs - an heroic image that has lived on ever since. Due to the pressure, the German right wing was pushed northward.

Eventually, seeing no victory being imminent, The entire German army retreated to points that could be fortified and defended. Moltke advised The Kaiser: "Sire - We have just lost the war". Wilhelm fired him.

The last open engagements on The Western Front during the entire war, occurred in the Autumn months and have become known as "The Race to the Sea". The culmination was the first battle of Ypres. First Ypres became known in Germany as Kindermod bei Ypern (the slaughter of the innocents at Ypres). 25,000 students who had volunteered in August were dead. But the toll was equally appalling on both sides. The BEF was obliterated, and French losses were just as severe.

By Christmas, a million soldiers were dead on The Western Front alone.

The War in The East

Meanwhile, in the east, Germany had sent only a small portion of its army to engage The Russians, as the goal was a quick defeat of France before turning the full attack on Russia. The Russian army was huge, but it was slow to mobilize and it was poorly lead - the two commanders of the army were not even on speaking terms! The Russians were poorly equipped and some went into battle without even rifles. Still, at first they were able to hold their own against The Germans. A decisive battle was fought at Tannenburg with a big German victory - their greatest of the war.Although it was only a small German force they were far more advanced than The Russians. The Russians had the far greater numbers, but they were mowed down by German shells. Almost a quarter of a million Russians were killed at Tannenburg. Czar Nicholas's repsonse was that to sacrifice so many for Russia's allies, was an honour.

The focus of the war, and site of the major battles, would be in the west - phase two of The Schlieffen Plan could not be implemented because phase one had utterly failed in the west. Germany's greatest fear - a prolonged war on two fronts, was realized.