Return to Table of Contents

"Also Sprach Zarathustra plays in the background"

The Cherokees "Great White Hope"

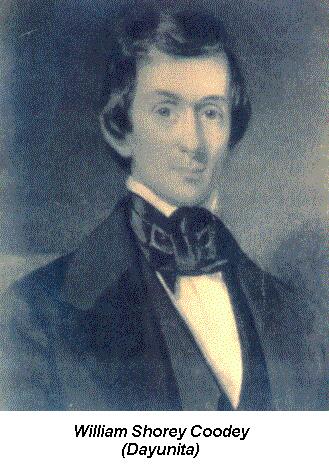

William Shorey Coodey (Dayunita)

by Lee Ross MacDonald

"Gloom hangs over the nation" read the Cherokee newspaper reporting on

the death of William Shorey Coodey, in Washington, DC, on April 16, 1849.

Their "great white hope" as he was sometimes called, was with them no more.

Gone was the hope and the glory of their beloved "Dayunita", his Cherokee

name meaning "the little beavers".

He had been born at Lookout Mountain, near the present Chattanooga,

Tennessee, in 1806, the eldest son of Jane (Jennie) Ross, who was the elder

sister of Principal Chief John Ross. John Ross had been prepared to rule

since his youth, for he was the eldest son of a first-born female, whose

mother had been a first-born female, also, and her mother another.

The first-born female of each generation had a special status, akin to

'head of the family', and the children were members of her clan, whatever

it was. So John Ross was the eldest son, with three first-born females directly

behind him. But Dayunita had four! He was like a living god from the day

of his birth.

He was not a robust child, but was more scholarly than most. The family

had a tutor for the children, and from there some were sent on for further

training at a college level. It is said that Prince William was the Cherokees'

first graduate from Princeton College. He later proved to have the finest

education in the Cherokee Nation.

In early days a Cherokee male was not considered a grown man until he

was about 25 years old (Cherokees knew those wild, young bucks!) But William

Shorey Coodey and his father were both delegates to the Constitutional Convention

in 1825. Home from his studies, Dayunita is said to have put the Constitution

together (others had been working on it for nearly ten years), but was too

young at the time to be given credit for it. That was remedied later, though,

because he is certainly given credit for the Constitution of 1839, in the

West, after the Trail of Tears.

HIS FATHER, Joseph Coodey, was from a large family believed to have come

into Virginia from Scotland. They were all good looking, well read, and one

book reported that there is hardly an old, notable family in the Old South

area who were not related to the Coodeys. That, then, is true of the white

as well as the red.

Joseph Coodey, a half-blood Cherokee, married well, into the family of

John MacDonald from Scotland. John MacDonald was one of the more popular

and prosperous traders because of his honesty (he was a member of the Masonic

Order, Scottish Rite, with their scruples and high-mindedness). He would

later become the Agent of Great Britain, and also of Spain. He saw to it

that his favorite grandson, John Ross, was given a good education for the

time, and got him off to a good start. The Cherokee training was from Charles

Renatus Hicks, who also became the mentor of William Shorey Coodey.

John Ross was married to Quatie Brown, said to be a full-blood, but she

was not. Her first marriage had been to a trader named Henley or Hensley,

and her first daughter was Susan Henley. When it came time to marry, Dayunita

chose Susan, whom he had known most of his life. Thus, Quatie was not only

his aunt-by-marriage, but his mother-in-law. The ties between the two families,

of two generations, became exceedingly strong.

WHEN THE CHANGES in the Cherokee government were being contemplated in

the late 1820's, it was decided that John Ross, being of the older generation,

would go first, and Dayunita would follow him. Under the Constitution, they

decided to call the office of President "Principal Chief", and that would

be taken by John Ross as presider over the government. But there was an uproar

about changing the old ways, with WhitePath and his followers resisting and

withdrawing.

Dayunita was sent to bring WhitePath back to the council, and in doing

so became their pipeline of information, their advisor and protector, their

"great white hope". His uncle could run the new civilian government, but

he would be the Oukah and continue the old ways, which were never abolished.

The system of heredity had changed by then to the white way, so the old ways

would continue through him.

DAYUNITA was a striking-looking man. He was slight of build, but strong

in character. He was considered to be one of the most handsome of Cherokee

men, which a miniature painting of him (now in the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa)

certainly proves. He was well educated, intelligent, studious, tactful and

conciliatory.The full-bloods put their full faith in him, and he became their

friend and ally until he died. After his death they turned to his younger

brother, Charles Ross Coodey, but Charles had not been given either the education

or the Cherokee training that his elder brother had.

Training in government began, and Dayunita served in several capacities.

Trips to Washington, D.C. with several Cherokee delegations contributed to

his education, and to his effectiveness. In Washington he made powerful friends,

who accepted him more than other natives because of his education, social

graces, and the fact that he was a practicing Mason.

Two children were born -- a boy and a girl. Life was sometimes good,

but too often disrupted by the white encroachment which never seemed to stop.

Then, when gold was discovered in the southern part of the Cherokee Nation,

the State of Georgia suddenly extended its limits to include the gold fields.

No Cherokees were allowed into the gold fields to mine their own gold, but

several books record that William Shorey Coodey was spotted in the gold fields.

Why not? He could pass for white, and in this instance evidently did, for

who would suspect a well-educated white-looking man who was attended by several

blacks?

The gold was put into a bank in Philadelphia, which at that time was

the banking center of North America. From that time onward it is never recorded

that Dayunita wanted for anything. There always seemed to be enough money

for comfortable living, travel, and later the furniture for his new home

in the West.

AFTER ANDREW JACKSON became president, Dayunita learned the true picture

not only from the treatment of the Cherokee delegations, but from his powerful

friends in Washington, DC. Without much fanfare, his mother took her family

to the "west" in 1834, before the storm could break. Dayunita took his family

with her and established a new plantation some miles east of Fort Gibson.

Then, it was back and forth for 5 years, serving the Cherokee people, and

his uncle, without ever once wavering in their right to remain in their old,

beloved country.

To prevent the forced removal of his people, Dayunita wrote letters to

the eastern newspapers which raised a furore, and made his name respected

throughout the eastern cities. Also, his letters to foreign countries caused

pressure to be put on the American government. And his friends in the Senate

protested the false treaty of 1835 so vigorously that it passed by only one

vote. But that one vote was enough.

From WashDC, 22 June 1838, he wrote three of his sisters, Maria, Louisa,

and Flora, who still lived at "Lookout": "...Cherokee business has ended,

for the present at least. Something has been gained but not all that, at

one time, so joyously expected...

"You will have seen from the papers that Gen's Scott with a military

force of six thousand troops is now in the Nation enforcing Schermerhorn's

treaty at the point of the bayonet. Several thousand Cherokees have already

been collected and are thus, no doubt, many of them on their way to the

West....Every breeze that comes up from the south is laden with the sighs

and moistened with the tears of distressed women and children. Pangs of parting

are tearing the hearts of our bravest men at this forced abandonment of their

dear lov'd country. Is it not a hard case?...the avarice and the thirsting

after....lands...and...property, of these most saintly Georgians must be

gratified - Yes, gratified at the expense of all the comforts and happiness

of the Cherokee even to the sacrifice of their lives!...Yet anxious as I

was for a removal to escape these troubles & these heart rending scenes

of expulsion by force, I can still place my hand upon my heart and say that

even my feeble voice was never raised to justify a treaty signed by unauthorized

individuals. I shall ever denounce it as villainous..."

Only a short time later he found himself the contractor for the first

wagon train to leave for the west. His account to a friend has been printed

in many books and articles. As written in "Cherokee Tragedy", page 312:

The people then started to move, and as they followed along the north

bank of Hiwassee River, their 645 wagons, 5000 horses, and large number of

oxen looked like the march of an army, regiment after regiment, the wagons

in the center, the officers along the line and the horsemen on the flanks

and at the rear.

The first attachment, led by John Benge, started toward Nashville on

October 1. William S. Coodey, its contractor, described the beginning of

the trek. He told of the caravan stretched along the road through a thick

forest. Knots of people clustered around certain wagons and lingered with

sick friends or relatives that must be left behind. The temporary huts covered

with boards and bark that had been their only shelter during the long, hot

summer were afire, sending up smoke, crackling and falling into heaps of

embers.

Dayunita wrote: "The day was bright and beautiful, but a gloomy

thoughtfulness was strongly depicted in the lineaments of every face. In

all the bustle of preparation there was a silence and stillness of the voice

that betrayed the sadness of the heart. At length the word was given to move

on". Coodey peered along the train and saw the venerable form of GoingSnake,

whose head was whitened by eighty winters and who sat astride his favorite

pony. The old chief forged ahead and led the way, followed by a company of

young men on horseback. "At this very moment a low sound of distant thunder

fell on my ear...It was noticed by several persons near me and regarded as

ominous of some future event in the west".

The next year, in WashDC, accounting to the "Ind. Bureau" for the events

of theTrail of Tears, and the murders of members of the Ridge Party, Dayunita

found himself in great trouble. He told the inquiring official that Ridge

and the others had not been murdered, but had committed suicide the minute

they signed that false treaty. He was banned from the government office for

several years.

ONCE AGAIN, at Fort Gibson on business, as recorded in a Chronicles of

Oklahoma article, he became so outraged at an army officer who was making

insulting remarks about "savages" and such, that he slapped the officer.

Of course he was immediately arrested. The account says that within the hour

his mother, about six miles away, heard about it. This was Jane Ross, mind

you, wealthy sister of Principal Chief John Ross. It is written that she

strapped on her gun, got on her horse, and rode headlong for the fort. There,

she challenged the commanding officer and demanded the release of her son,

which she promptly got. The commander, reporting on the incident, wrote "You

would have released him, too, if you had seen that little woman riding for

the fort like a thunder storm, with a tornado behind her!"

ONN ONE TRIP HOME from Wash. D.C., Dayunita learned that his only son

had been kicked by a horse, and had died. The next year he returned home

to find that his wife, Susan, had died. In despair, he rode, in the dead

of winter, past Fort Gibson to the Arkansas River. There he looked across

the river to a shelf of rocks with ice covering them. Too depressed to remain

in his old home, he gave it to a niece and built another plantation on the

west side of the river. He called it "Frozen Rock".

His daughter was enrolled in Peropsco Female Institute in Maryland. But

in 1842 he took a new wife, a distant cousin, the young daughter of the merchant,

Richard Fields. The parents thought that there was too much difference in

their ages, but Elizabeth Pack Fields and Dayunita eloped in his carriage

which took them to "Hunter's Home" in Park Hill. There, at the home of his

cousin and her husband, the two were married in a private ceremony by the

Reverend Stephen Foreman.

Their honeymoon trip, on the way back to the Congress in Washington,

DC, took them to New York City and Philadelphia. There they purchased rosewood

and mahogany furniture for their new home at Frozen Rock. Also a piano. The

house would become one of the leading social centers for the Cherokee Nation.

It was built out of double walnut logs, cut from trees on the property,

and polished on both sides. During the Civil War a Colonel Charles DeMorse,

of the Texas 29th, wrote from Coodey's Creek in the Cherokee Nation. His

letter was published in the Clarksville, Texas, Standard:

"...the deserted residence at Frozen Rock is a lovely place. The house

of six rooms, well fitted with furniture -- numerous out houses attached,

is about 50 yards from the margin of a high bank, over looking the Arkansas;

at this point is a stately stream, and makes a graceful bend at the right

in full view of the portico of the house. Before the house the surface of

the ground is rounding, sloping to the edge of thebank --then a steep descent

to the river.Before the house at regular distances are black walnut, the

black locusts, native here, and of large size, some large catalfias in bloom,

cherry trees and Pear trees. At the left a garden in which are some hollyhawks

and other simple flowers, and to the left of that a large orchard of Apples

in full bearing, but small yet. In the rear is the handsomest walnut and

Locust Grove, of large tall trees, interspersed with slippery Elm, that I

have ever seen: look like a park. On the right are out-buildings and fields,

and a lane with a winding path descending to the river, on the one side of

which is a spring. It is a very beautiful place.

"At the left of it, a quarter of a mile, is another residence. Both are

settled by brothers named Coodey, one of whom is now here, and lives near

Kiamitia. The name Frozen Rock is derived from a porus slate bank of the

river, between the two houses, from which the water exuds, and in the winter

time presents an unbroken surface of ice..."

IN THE EARLY 1840's a new combined Cherokee government began to

function.William Shorey Coodey was elected to be the Senator from the Canadian

district on the west side of the Arkansas River. There, he was elected President

of the Senate. As such, he was Acting Principal Chief in 1846 during the

absence of the Principal Chief and also the Assistant Principal Chief.

SEVERAL MORE TRIPS to WashDC became necessary, as he was trusted by the

Ross Cherokee faction and also by the Old Settlers, as he and his mothers'

family had become members there in 1834. When he was alone he stayed at a

leading boarding house or hotel, but when his wife was with him his friend,

Daniel Webster, insisted that they stay in his home.

During one of these visits, Daniel Webster spoke of how the Cherokee

Nation had changed, and he was explained that because of WhitePath and his

fullblood followers the old ways had not gone away, but only underground.

"But now they have no king!" Daniel Webster said.

"Sure they do," Dayunita said. "You're looking at him."

It is said that Daniel Webster blanched white, reached out his arm to

his Cherokee friend and said, "My dear friend, don't ever let anybody in

this city know that, but me! If you do, you might not live till morning!"

IN 1845, A GROUP met at Frozen Rock for a "mammoth Christmas Party" on

December 26th, and the next day Dayunita left with them for Texas. It was

an important visit to make peace with the Comanches. But the trip and the

cold winter proved too much, and Dayunita returned home before the final

negotiations.

Once, from Philadelpha where he had attended an abolitionist meeting,

he wrote his uncle, John Ross, with the advice that it would be advisable

for Cherokees to "stay out of it". He wisely write: "Our silence was the

better and indeed only proper course".

He had become a slave-owner, himself, from accident and necessity. Several

books report that on one trip to WashDC, along with his wife, they had boarded

a steamship at their own private dock, Frozen Rock (which was used by the

whole community). On board was a negro slave woman along with her six children.

Fearing that when they got to New Orleans they would be sold separately,

the black woman appealed to Elizabeth to buy them all. Her heart going out

in sympathy, Elizabeth appealed to Dayunita to buy them, and he did. For

$1,500 cash! (about 45,000 dollars today). According to Theda Purdue in "Slavery

and Cherokee Society" it was not too unusual for a black to appeal to a Cherokee

to buy them, as Cherokees were usually much kinder to them than any white

master.

In New Orleans Dayunita put them on a steamboat going upriver to be delivered

to Frozen Rock (after all, he knew all the ship captains). Then he and his

young wife continued to Washington City.

Another story is told about one of his blacks named Rabbit. Rabbit was

elderly and wouldn't work, so Dayunita agreed to allow him and his wife to

sell cider and gingerbreak to travelers who forded the river on Coodey's

property and to charge a fee for directing strangers across the river which

was full of eddies and suction holes.Dayunita's only remaining daughter,

Ella Flora Coodey Robinson, told her great-grandson, the present Oukah: "Once

when father was home Rabbit came to the house with an offer to buy his freedom.

Father said OK, how much do you think you are worth? The old black man said

two bits". Then she shook her head and said, "We never did get the two bits!"

IT WAS ON ANOTHER trip toWashDC, some years later, as the Cherokee delegate

to Congress, in 1849, that he died. In January, his daughter had come to

Washington City from Maryland, to see him. While there she took sick and

died. They buried her in the Congressional Cemetery.She was only 17.

Dayunita was ill, also. Four months later he also died, his wife in

continuous attendance, along with their son and young daughter. He was buried

in the Congressional Cemetery, beside his beloved elder daughter, Henrietta.

Among his pall-bearers were Senators John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and his

special friend, Daniel Webster.

A friend wrote from Washington City, April 17th: "My dear....."

I have been confined to my room and bed almost all the time since you

left, and have just got up and gone to my window to see the funeral procession

of our friend Coodey. He died yesterday morning, having gradually grown worse

since you saw him.

Much respect has been paid to his remains. A large procession of Masons,

dressed in their Regalia, the officers of the Ind. office, and numerous friends

followed in the funeral procession which was headed by the "Marine Band"

ordered to attend by the Secretary of the Navy....he was buried in the

Congressional Burying Ground by the side of his Daughter. Few men have died

here who were more respected than was Mr. Coodey..."

From WashDC, a reporter for the Baltimore Sun reported:

"William S. Coodey, a distinguished citizen of the Nation of the Cherokee,

died here yesterday, and was buried this afternoon with every testimonial

of respect and regard. His remains were attended to the grave by the Masonic

Lodges, as well as by many of the most respectable of our townsmen and visitors

from elsewhere. Mr. Coodey was a well educated and well principled person,

and has held high and honorable employments from his nation, both in their

councils at home and as a delegate here. He was much esteemed, and will be

much regretted."

Later, on May 21, 1849, the Cherokee Advocate published:

WILLIAM SHOREY COODEY

In the last number, we announced the death of our distinguished and lamented

fellow citizen, Mr. William Shorey Coodey. Since then full particulars have

been received of this melancholy event, which, though not unexpected, has

caused an expression of universal regret throughout the country, and is deeply

deplored, as it has deprived the Cherokee Nation, while yet in the meridian

of his life, of one of its most able and patriotic citizens.

Mr. Coodey was about forty-three years of age, and nephew to Mr. John

Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokees. He was born in the Cherokee country,

East of the Mississippi, and resided there until 1834, when he removed and

settled in the country now occupied by the Cherokees, where he lived up to

the time of his death, which, as before stated, took place in the city of

Washington, at half past 6 o'clock, A.M, Sunday, the 16th day of April.

Mr. Coodey was no ordinary man -- Possessed of a strong mind, a quick

perception, great logical and conversational powers, extensive reading, a

memory never at fault, a demeanor strikingly expressive but always dignified,

and a physical courage equal to any emergency; he was calculated to adorn

whatever position, public, or private, might be assigned him..."

Gloom, indeed, hung over the nation. The beloved one was gone.

The End.

Return to Table of Contents