Case study of shifting cultivation

Papua New Guinea

A case study of shifting cultivation in a traditional economy: the Kaluli

There are very few areas in Papua New Guinea where an agricultural system,

such as we have described here, still operates. Once widespread, this system

is now restricted to remote areas where European influence is slight. One

group of people who still operate such a system are the Kaluli who live on

the Papuan Plateau in the Southern Highlands Province of Papua.

An important source of food is sago which is made from the palms which grow

naturally in the swampy areas near the water courses. In addition, the Kalui

maintain gardens in which they grow bananas, sweet potatoes, taro, sugar cane,

and green, leafy vegetables. Besides these traditional crops, a few introduced

crops such as tomatoes, corn, pumpkins, pineapples and pawpaws are also grown.

The Kaluli have two different methods of making their gardens.

Level areas within the forest are cleared and planted in the manner described

above. The main crops in these gardens are the root crops-sweet potatoes and

taro-and other quick-maturing crops such as sugar cane and a plant related

to sugar cane, pit-pit.(The flowering head of the pit-pit is the part which

is boiled and eaten.) These gardens are occasionally weeded before they mature

in less than a year.

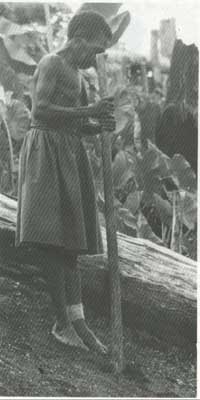

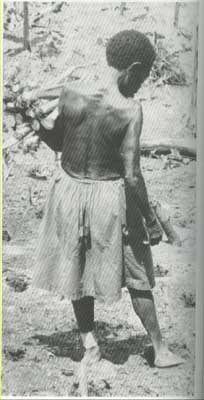

A different technique is used for growing bananas, breadfruit and pandanus,

all of which are planted in gardens made on the steep slopes of ridges. The

planting material is placed in holes made with a digging stick under the forest

cover. After the newly planted shoots have struck, the forest canopy is felled

over the plants, which then grow up through the tangle of fallen leaves and

timber. The bananas are ready for harvesting in about twelve months and continue

to bear for at most another twelve months, the pandanus and breadfruit take

several years before they commence to bear.

This gardening system may appear to be strange but, in fact, it is an efficient

system well adapted to the physical environment in which the Kaluli live.

The soils on the slopes are shallow; the rainfall is not only high-over 5000mm

annually-but it falls in storms of high intensity. Under these circumstances,

any ash from burning would be washed away with the exposed surface soil before

the planted crop could provide sufficient cover to prevent rapid erosion.

By felling the trees on top of the crop, the leaves and twigs of the fallen

trees form a protective cover for the soil and, as they rot slowly, some humus

is added to the soil. The felling of the timber destroys only a few plants

because the branches tend to hold the trunk and main branches clear of the

ground.

The 1400 Kaluli people occupy an area of about 700 square kilometers. There

are about 20 groups each of about 70 people who occupy a communal house which,

isolated in the forest, is usually 5 to 8 kilometres distant from that of

adjoining groups.

Because the Kaluli shift their gardens every few years, they constantly relocate

their communal house. As the producing banana gardens near exhaustion, the

men decide upon the location of their new gardens. The site chosen depends

upon the availability of suitable gardening lands and the proximity of stands

of sago. A new house is built and gardens are made before the old house is

abandoned, When the old gardens are exhausted, the shift is made and a new

pattern of movements between house, gardens, forest and sago swamps is established.

It is apparent that, given these constant shifts of residence and the irregular

nature of contact with outsiders, networks of communications and nodes do

not develop. In 1964 an airstrip was built in the area and a mission post

was established. In 1966 an aid post was built and these formed the nucleus

of a small settlement. For a time, the Kaluli tended to concentrate around

the mission and the aid post, and some planted gardens. However, in little

more than a year, the Kaluli had moved away to seek garden lands in the forest

where they could re-establish their accustomed patterns of gardening.