|

Authored by Lawrence E Holder, MD, Clinical Professor of Radiology, University of Maryland School of Medicine; Consulting Staff, Department of Radiology, Baltimore Veterans Affairs Medical Center I. INTRODUCTION Background: Although controversy continues regarding the term, definition, and process of diagnosis, the presence of sympathetically maintained pain is accepted as an etiology for, or at least as a significant component of, many regional pain problems. Pathophysiology: Many biomechanical factors have been considered, beginning with tissue injury as an initial inciting event, with substance P, histamine, and prostaglandins all possibly involved. Other possible etiologies include vasodilatation, shunting, and regional hypoxia associated with nociceptor stimulation, as well as the role of alpha-adrenergic receptors in maintaining and controlling thermoregulatory modulation. Segmental involvement of 1,2, or 3 rays in the hand has been reported infrequently, according to Kline and Holder, and bilateral involvement is rare to nonexistent. In the lower extremity (most often foot and ankle), a less well-defined clinical pattern also is associated with a similar spectrum of pathophysiologic speculations. In the knee, potentially sympathetically related postoperative and posttraumatic signs and symptoms have been ascribed to RSD or other neuroregulatory processes but with less accepted clinical or diagnostic standards of reference. More recently, the term complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) has been introduced to encompass a variety of chronic pain syndromes, with RSD labeled as type I. All sympathetically maintained pain syndromes (SMPS) may not be RSD. In the lower extremity (most often foot and ankle), a less well-defined clinical pattern also is associated with a similar spectrum of pathophysiologic speculations. In the knee, potentially sympathetically related postoperative and posttraumatic signs and symptoms have been ascribed to RSD or other neuroregulatory processes but with less accepted clinical or diagnostic standards of reference. More recently, the term complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) has been introduced to encompass a variety of chronic pain syndromes, with RSD labeled as type I. All sympathetically maintained pain syndromes (SMPS) may not be RSD. Frequency: *In the US: The incidence of RSD following trauma is difficult to estimate, since the literature is replete with studies in which clinical criteria for the diagnosis of RSD vary dramatically, with many often equating unexplained pain to RSD. For example, upper extremity RSD, as understood and treated by hand surgeons, is described differently than lower extremity RSD diagnosed by rheumatologists or hip RSD described by obstetricians. Some authors suggest that 8-10% of patients with fracture develop RSD, but in the author's experience, the frequency is much lower. Mortality/Morbidity: Most RSD patients recover completely over time. Uncommonly, the syndrome progresses to the point of incapacitation and a "claw hand" is observed. Sex: In the upper extremity, the author's experience demonstrates a clear female preponderance, especially in patients presenting to the orthopedic surgeon. Age: Patients younger than 50 years predominate. In the upper extremity, orthopedic surgeons see children only rarely. Rheumatologists, who generally use less strict criteria for diagnosis, report a slightly higher frequency of involvement in children. Similarly, pediatricians report a moderate frequency of lower extremity neurovascular or neuroregulatory disease in children that has been termed RSD. In these children, a bone scan pattern often reveals marked decreased tracer uptake on delayed images compared to increased uptake in adults; therefore, this may represent a different condition, such as pseudodystrophy. Anatomy: RSD involving the hand, wrist, shoulder, ankle, and foot has been established, with diffuse involvement of adjacent carpals or tarsals, metacarpals or metatarsals, phalanges, and, frequently, the distal forearm or leg. Rarely, segmental involvement of 1, 2, or 3 rays of the hand is observed. Involvement of the knee, although described, is less well documented and along with focal pain conditions in the hip (often interchangeably termed RSD or transient osteoporosis) may be a different process. Clinical Details: Radiologists and orthopedic surgeons usually agree to define RSD (as stated by Schutzer) as an "excessive or exaggerated response to an injury of an extremity, manifested by four somewhat constant characteristics: (1) intense or unduly prolonged pain, (2) vasomotor disturbances, (3) delayed functional recovery, and (4) various associated trophic changes." The key feature is pain, which often is the initial presenting symptom. Various clinical schemas have been proposed that relate stages of disease to signs and symptoms and the time elapsed since the inciting event. One example of staging by Rosenthal and Wortmann is as follows: *Stage 1 - Duration of weeks to months. The limb has nonfocal pain, swelling with associated joint stiffness and decreased range of motion, and increased skin temperature. *Stage 2 - Duration of 3-6 months. Pain continues but decreases over time. Swelling evolves into thickening of the dermis and fascia. Early signs of atrophy and osteoporosis become evident, and the extremity becomes cooler. *Stage 3 - Atrophic stage. Pain continues and atrophy is exacerbated by continued decreased range of motion and increased joint stiffness. The extremity is cooler with decreased vascularity. Preferred Examination: Nonimaging diagnostic testing II. DIFFERENTIALS: Osteoarthritis,

Primary Other Problems to be Considered: III. X-RAYS Findings: Osteoporosis, although found in as many as 60% of patients with upper extremity RSD, is not specific, often representing changes of disuse secondary to the pain associated with RSD. Occasionally, soft tissue swelling or diffuse soft tissue atrophy may be seen; these are nonspecific findings. IV. MRI Findings: MRI changes in established RSD rarely have been evaluated, and as with studies using other modalities, the definition of RSD has varied considerably. In one study by Schweitzer et al involving the lower extremity (n=35), soft tissue thickening with and without contrast enhancement (n=31) was demonstrated without any marrow changes, while in another study of the upper extremity (n=17) by Koch et al, no marrow changes and only inconsistent soft tissue or muscle signal changes were seen. In the hand, Sintzoff et al used MRI to detect what was believed to be bone marrow edema and then equated bone marrow edema to RSD. MRI thus is not an established technique in the imaging evaluation of RSD. V. ULTRASOUND Findings: A single-power Doppler study by Nazarian et al involving the lower extremities suggested increased flow without side-to-side asymmetry in patients with RSD. Ultrasound thus is not an established technique in the imaging evaluation of RSD. VI. NUCLEAR MEDICINE Findings: Three-phase RNBI is performed primarily because the differential diagnosis often includes infection or other lesions for which information about the perfusion to the extremity (phase I) or relative vascularity of the extremity (phase II) is helpful. For regional RSD of the hand or foot, the hallmark on the radionuclide angiogram (RNA; phase I) is diffuse increased perfusion to the entire extremity, including the distal forearm or leg and, occasionally, reaching the shoulder or hip, even when the inciting lesion is distal. Similar diffuse increased vascularity, manifested by diffuse increased tracer accumulation on blood pool or tissue-phase images (phase II) is seen. On these images, juxta-articular accentuation may be seen. RNA findings are abnormal in approximately 40% of patients and blood pool findings in approximately 50%, most often in clinical stage I or II of the disease. Delayed images demonstrate diffuse increased tracer throughout the hand or foot, including the wrist or ankle, with juxta-articular accentuation and, often, proximal uptake involving the forearm or leg and, occasionally, the shoulder and arm or hip and femur. Activity in the hands or feet usually is more prominent proximally than distally, but the amount of abnormal tracer uptake has not been correlated with clinical severity. Quantification occasionally has been helpful but is not used routinely. Degree of Confidence: In the lower extremity, patients with severe infection, especially if underlying diabetes mellitus is present, may demonstrate diffuse increased delayed image tracer uptake on RNBI performed to diagnose osteomyelitis. This is not usually a diagnostic issue clinically. VII. INTERVENTION Intervention: Radiologic intervention is not available. VIII. PICTURES Caption: Picture 1. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the hand. Delayed image palmar view reveals increased tracer diffusely involving the entire right wrist, metacarpals, and phalanges, with juxta-articular accentuation. Relatively less increased uptake is observed distally, but all areas are involved. The dot of increased activity distal to the third ray is a hot marker indicating the right side.

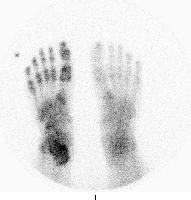

Picture Type: Photo Caption: Picture 2. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the foot. Delayed image plantar view reveals increased tracer uptake diffusely involving the lowermost right leg, ankle, tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges. Uptake is less distally than proximally, but all areas are involved. The dot of increased activity distal to fifth toe is a hot marker indicating the right side.

Picture Type: Photo IX. BIBLIOGRAPHY Amadio PC, Mackinnon SE, Merritt WH, et al: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome: consensus report of an ad hoc committee of the American Association for Hand Surgery on the definition of reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991 Feb; 87(2): 371-5[Medline]. Driessens M: Infrequent presentations of reflex sympathetic dystrophy and pseudodystrophy. Hand Clin 1997 Aug; 13(3): 413-22[Medline]. Fournier RS, Holder LE: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: diagnostic controversies. Semin Nucl Med 1998 Jan; 28(1): 116-23[Medline]. Holder LE, Mackinnon SE: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy in the hands: clinical and scintigraphic criteria. Radiology 1984 Aug; 152(2): 517-22[Medline]. Holder LE, Cole LA, Myerson MS: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy in the foot: clinical and scintigraphic criteria. Radiology 1992 Aug; 184(2): 531-5[Medline]. Kline SC, Holder LE: Segmental reflex sympathetic dystrophy: clinical and scintigraphic criteria. J Hand Surg [Am] 1993 Sep; 18(5): 853-9[Medline]. Koch E, Hofer HO, Sialer G, et al: Failure of MR imaging to detect reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the extremities. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991 Jan; 156(1): 113-5[Medline]. Mackinnon SE, Holder LE: The use of three-phase radionuclide bone scanning in the diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J Hand Surg [Am] 1984 Jul; 9(4): 556-63[Medline]. Nath RK, Mackinnon SE, Stelnicki E: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. The controversy continues. Clin Plast Surg 1996 Jul; 23(3): 435-46[Medline]. Nazarian LN, Schweitzer ME, Mandel S, et al: Increased soft-tissue blood flow in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the lower extremity revealed by power Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998 Nov; 171(5): 1245-50[Medline]. Poncelet C, Perdu M, Levy-Weil F, et al: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy in pregnancy: nine cases and a review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999 Sep; 86(1): 55-63[Medline]. Rosenthal AK, Wortmann RL: Diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Compr Ther 1991 Jun; 17(6): 46-50[Medline]. Schiepers C: Clinical value of dynamic bone and vascular scintigraphy in diagnosing reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the upper extremity. Hand Clin 1997 Aug; 13(3): 423-9[Medline]. Schutzer SF, Gossling HR: The treatment of reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984 Apr; 66(4): 625-9[Medline]. Schweitzer ME, Mandel S, Schwartzman RJ, et al: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy revisited: MR imaging findings before and after infusion of contrast material. Radiology 1995 Apr; 195(1): 211-4[Medline]. Sintzoff S, Sintzoff S, Stallenberg B, Matos C: Imaging in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Hand Clin 1997 Aug; 13(3): 431-42[Medline]. Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, Goris RJ: Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet 1993 Oct 23; 342(8878): 1012-6[Medline]. Wesselmann U, Raja SN: Pain: nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy and causalgia. Anesthesiol Clin North America 1997; 15: 407-27. Wong GY, Wilson PR: Classification of complex regional pain syndromes. New concepts. Hand Clin 1997 Aug; 13(3): 319-25[Medline].

|