By Jeff Gordinier

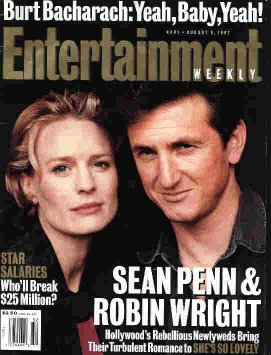

Image credits: Kurt Markus

August 8, 1997

They didn't

have guns, but she thought they did. They crept up to Robin Wright Penn's

Toyota Land Cruiser with their hands stuffed in their pockets, simulating

pistols. They ordered her to hand over the keys. "If I was alone, it would've

been less harrowing," she says. "It's like, 'Take the car, take the f---ing

house, take everything.'"

But she

wasn't. Her two children--daughter Dylan, 5, and son Hopper, 3--were still

strapped in their seats. So before surrendering the keys, the woman who

played Forrest Gump's inamorata had to persuade two carjackers to let her

kids climb out of the car.

Later that

May night in 1996, her husband, Sean Penn, marveled at his wife's composure.

(In true Southern California style, Robin's 911 call was all over the airwaves.)

"She was amazing," he says. "They played it on the news, and I heard her.

Her voice was so calm and clear about what had happened."

Hearing

Sean Penn talk about staying calm is a little like hearing the Pope deliver

a homily extolling the pleasures of Pulp Fiction. At 36, Penn has

played his share of hotheads and scumbags. A purse-snatching hooligan in

Bad

Boys. A merciless rapist in Casualties of War. A budding thief

in At Close Range. An ice-cold killer in Dead Man Walking.

And, in Carlito's Way, a lawyer. Back in the '80s, when his four-year

marriage to Madonna was snowballing into a kind of tabloid Iliad

and Penn was practicing his right hook on paparazzi, he even got to do

some research, courtesy of the Los Angeles County penal system. He spent

30 days behind bars after clocking a film extra in 1987; he had his driver's

license revoked. Thanks to these events, Sean Penn can speak with great

conviction on the forces that lead young men to commit acts of mayhem.But

when a couple of teenagers threatened his wife and kids a year ago, right

in the driveway of their Santa Monica home, Penn found himself looking

at crime and punishment from a fresh vantage point. "That was a toughie,"

he says, leaning back and taking an extra-long drag of nicotine. "There's

the death penalty as society deals with it and legislates it, and I'm against

it. But then there's each individual's rage. That got to me, that situation.

Whenever I've been on the other side of the law, as it were, I've never

conspired to do malice toward somebody, so I didn't feel like now the shoe

was on the other foot or anything like that. I just felt that I wanted

to see some serious justice done."

There are times, Penn knows, when it pays to remain calm. Usually, people expect Sean Penn to drink them under the table in some dim, sticky-floored saloon--the kind of cheap-hooch dive that his late friend Charles Bukowski, the Los Angeles writer and Olympian boozehound, used to rhapsodize about. Lots of journalists have come to Los Angeles nursing "a romantic notion of an outlaw actor," as Penn says, but today he's holding court in a dainty, lavender-scented hotel room, watching the fog burn off the Pacific.

Morning fog. Yup, it's two hours before noon, he's just dropped Dylan off at school, and the outlaw actor is itching for wild turkey. A turkey sandwich, that is. "They only have the flat grill, which is all greased with lard. Can't do that," he explains while negotiating with room service. "What about a cold turkey sandwich? That would be really swell. I'm not a breakfast eater."

Sheesh. The only law Penn is breaking is the "no smoking" policy that governs this deodorized suite. He's consuming cigarettes like airplane peanuts, and nobody's stopping him, because Penn is not the kind of guy you chastise for small vices.

So who knows what to make of this polite, law-abiding, early-rising, calorie-conscious, really swell guy masquerading as Sean Penn? Perhaps scientists have perfected the technology in Face/Off and Penn has swapped mugs with, say, Michael J. Fox? "I'm getting ready to do a movie, and I've got my kids full-time now," he murmurs by way of explanation. "A couple of years ago, Robin and I weren't together, so I would have half the week off."

The laugh--low, stuttered, vaguely zonked--suggests that giving Sean Penn half a week off is a bit like handing Butt-head a bucket of cherry bombs. But lately Penn hasn't had time to play with matches. For the first time since the Reagan years, he's got three movies coming down the pike at once: Nick Cassavetes' She's So Lovely, a raunchy romantic fable that landed Penn the Best Actor prize at the Cannes film festival, opens Aug. 29; The Game, a twisted, psychotropic thriller from director David Fincher, the man responsible for Seven, hits Sept. 12; and U-Turn, a satire on violence from Oliver Stone, arrives Oct. 3. Penn can calm down all he wants; directors are always going to want to cast him as a head case. "Sean was shooting She's So Lovely at the time and he said, 'I don't have a lot of time to devote to coming up with this character,'" says Fincher. "I said, 'Sean, this is a guy who's charming and kind of f---ed up. It's you. You just have to show up.'"

In July, the actor who says he hates acting flew off to Australia for a fourth film--The Thin Red Line, the first movie that Terrence Malick has directed since 1978's Days of Heaven. "We've known each other for a long time," Penn says of Malick, the lyrical Texan who ducked beneath the Hollywood radar for two decades. "I drive across country a lot, so I used to visit him in Austin. He never left the movie business, in his mind; he just moved back to Texas. I don't think he was ever in the Hollywood grain."

Penn knows a thing or two about self-imposed exile. Tim Robbins, who directed him to an Oscar nomination--his first-- in 1995's Dead Man Walking, heralds him as "the best actor of my generation," but Penn keeps insisting that he doesn't want to act at all. (Unless, of course, he's wooed by the taboo-smashing auteurs behind Austin Powers. "I was on the floor with that one," he says. "If I could play his '70s American counterpart, I would do it in a flash.") For most of the '90s, he's poured his time, cash, and juice into writing and directing 1991's The Indian Runner and 1995's The Crossing Guard, two bracing indie films that fathomed issues perilously close to home--the consequences of violence and booze.

"You can't get paid $20 million for the kind of movies I want to do," he admits. "There've been a couple of times when I've gotten the offer to do the odd one that'll make the bank big forever. But you start on page one of the script, knowing what the money is, and you're praying that you're gonna find some reason to do it." He sighs. "You can't find a reason." In fact, the only thing giving Penn a hangover this morning is the box office champion of 1996. "I tried to watch Independence Day last night, because it was on cable," he says. "I thought it was a big ridiculous crock of sh--."

Truth is, Penn's flight from the mainstream is precisely what saved him from that scatological fate. While legions of his Brat Pack compadres are turning into punchlines (just try imagining Charlie Sheen as a death-row convict), the guy who played stoner saint Jeff Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High has become his class' unlikely Most Likely to Succeed--well respected, if not quite respectable. With a closet full of ubiquitous black suits, an invincible grin, and a James Dean-style swoop of hair that he trims himself, Penn can even manage to look sort of dashing. "Sean has always played a bad boy as a younger man, but now he seems to be coming of age as a bad boy as an adult, more in the mold of Mitchum and Bogart," raves Oliver Stone. "His face is sort of settling into a rugged handsomeness."

But the trip to Cannes would take 10 years. Cassavetes was dying of cirrhosis, so he and Penn tapped another against-the-grain comrade--Harold and Maude's Hal Ashby--to take over as director. Ashby developed cancer; by 1989, both he and Cassavetes were dead. Determined, Penn eventually struck out to direct the movie himself, but this time the financiers were balking at one tiny clause in his contract: Penn wanted to shoot the movie in black and white.

It

was John's son, actor-director Nick Cassavetes, who finally roused She's

So Lovely from dormancy, nailing down a $16 million budget from Miramax

and asking Sean Penn, Robin Wright, and John Travolta to star--in full

color. (The Cole Porter estate asked him to change the title.) If Cassavetes

was looking for a couple that could convey the proper degree of crazy love,

he'd come to the right place. "The beginning and the end of every day is

how Sean and Robin are getting along," Cassavetes says. "You would think,

Buddy, get over it. But if they have a bad morning, Sean's broken up about

it."

On the other

hand, if the Penns were looking for a way to snuff out speculation about

their turbulent relationship--something they're shy about dissecting in

public--it might've been smarter to star in a volcano movie.

Raw, romantic, and tempestuous, She's So Lovely is bound to get everyone guessing about the nature of their marriage; if the two of them have a hard time seeing the parallels, well, they're probably the only ones:

Robin: "I didn't even think about it, did you? The depths of it? It just sort of..."

Sean: "No, there were things that--of course, you'd suddenly hit upon something that was paralleling an incident on that day."

Robin: "Oh, yeah."

Sean: "Something that felt very... Well, your frame of reference would have a kind of incident that its foremost version had to do with...our own..."

Robin: "Your psyche would remember having been there. With us."

Sean: "Yeah. Yeah."

On the other hand, Penn refers to their most severe period of separation as "a nightmare." In 1993 the Malibu fires reduced his mansion to ash; he soon rolled an aluminum Airstream Sovereign trailer onto the blackened land and moved into it, alone. He was seen courting Elle Macpherson and Jewel; by the fall of 1995 he was telling journalists that Wright had dumped him, that they might never see each other again. ("I don't think it's good to do an interview and be drinking," Penn chuckles now.) Then, on April 27, 1996, Wright changed her surname to Penn. "Tradition," she says. "I love that. Get married, take the man's name." "Being married? Yeah, it's great," Sean says. "Marriage ain't easy, but it's great most of the time. I love Robin. I've always loved her."

Wait. Take a moment to ask about this improbable leap--from excommunication to matrimony in six months flat--and Penn answers with an epigram from Ralph Waldo Emerson: "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds."

He offers another maxim, one attributed to Joni Mitchell. "I don't like monotony," he says. "But this aids me in the area of romance, and it's something you can think about: 'If you want the same same every day, f--- somebody new. If you want endless diversity, stay with the same one.'"

Which leads, finally, to one word: "Belief."

"I like to believe that love is a reciprocal thing, that it can't really be felt, truly, by one," Penn says. "That on a romantic level, if you feel it about somebody and it's pure, it means that they do too. And if you keep believing that, they come around."

Sounds a lot like irrational obsession.

"Well,"

he says, "I think life's an irrational obsession."

ROBIN

WRIGHT PENN IS SITTING just three blocks from their old house in Santa

Monica--the site of the carjacking--when a homeless woman shuffles up to

a Starbucks on the corner, exhausted, heaped in hillocks of gray rags.

"That woman has been on the street since--Jesus, 12 years now. I remember

seeing her when I first moved to Santa Monica," Wright muses. "And she

won't ask for money. Some days, she doesn't take it if you just offer it.

She has a pride."

Wright recognizes

the woman, but the morning crowd at Starbucks takes little notice of Wright.

Up close, it makes absolute sense that Rob Reiner chose the actress to

play the object of worship in 1987's The Princess Bride; suddenly,

her husband's "irrational obsession" seems completely sane. Wright is blond,

high-cheekboned, classically beautiful, with a face that's as delicate

and refined as Sean Penn's is scarred and meaty.But she doesn't attract

a single shoulder-tapping, ballpoint-pushing, lemur-eyed fan. "I wouldn't

like that fame," she says. "I like being able to sit right here. I mean,

Sean gets that a lot. It would drive me nuts."

If a low profile

is a high priority, she's on the right track. Over the years Wright has

turned down flashy, star-minting roles in The Firm, Jurassic

Park, and Batman Forever in favor of quiet, pint-size fare like

Moll

Flanders and The Playboys. Her choices, she concedes, have led

much of the industry to reach a pretty widespread conclusion about Robin

Wright Penn. "They think I don't want to work," she sighs. "That's not

true. I'm just waiting for the right thing--and trying to be a mom and

have a husband who does the same thing."

And now, just as Hollywood prepares to embrace the Penns, the Penns are getting ready to leave. Sick of Los Angeles and shaken by last year's carjacking (even though the perps were arrested and put behind bars), they're packing up for a small town north of San Francisco, a place where, as Wright puts it, "the phone will not ring as much because not as many people will have the number."

"There's not a lot of room to be inspired by anything here," Penn explains.

In other words, there are times when it pays to remain calm--even if Penn's definition of calm isn't quite the picture of small-town serenity. "As Bukowski used to say, just hide out for four days," he says. "Pull down the drapes. Don't even think. Don't read. Just be there for four days with the drapes down. You come outside, you feel 100 percent stronger."