Genocide by Sanctions - a video illustrating conditions in Iraq by former Attorny General Ramsey Clark, made in 1997.

|

Genocide by Sanctions - a video illustrating conditions in Iraq by former Attorny General Ramsey Clark, made in 1997. |

|

"In a small grocery store in a poor area of Baghdad early one morning I watched a child of perhaps five...proudly doing a terribly important errand: he bought one egg. A tray of 30 eggs exceeds a university professor's monthly salary... As he left, the child dropped the egg. He fell to the floor, frantically trying to pick the shell, yolk and white, with his small hands, tears streaming down his face." - Felicity Arbuthnot. Appeared in What Has Been Done to Iraq? by K. Shreeram, Mid-East Realities 11/98

Table Of Contents

I. Deterioting Conditions from 1990-91

(Back to Top)

While few observers doubted the deteriorating plight of the ordinary Iraqi people, and while

Bush repeatedly emphasised that the option of further military action against Iraq was still

open, the punitive sanctions - including a (defacto if not de jure) ban on imports

of food and medicine - remained in place. WHO and UNICEF had warned of the 'catastrophe' that

would beset Iraq if sanctions were not lifted, but Washington and London remained largely oblivious

to this concern. In May 1991 the White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater repeated the familiar

refrain that 'All possible sanctions will be maintained until he [Saddam Hussein] is gone.' There

was plenty of evidence that sanctions were devastating the Iraqi people, but no evidence that

they were undermining the Ba'athist regime. The deteriorating health of the Iraqi population became increasingly obvious through the

summer of 1991, though the US and Britain - as lead players on the Security Council - seemed

reluctant to agree any relaxation in sanctions. These countries even went so far as to block

Iraq's unilateral efforts to export $1 billion-worth of oil to buy food and other essential

products, such as water purification tablets. A few states connived with Iraq to break the

UN-imposed sanctions, but Iraqi imports remained only a fraction of pre-war levels. Jordan, for

instance, was found to be trading with Iraq in violation of UN stipulations, as shown by an

Iraqi-Jordanian Joint Committee document, with minutes signed by Abdul Wahid al-Makhzumi,

adviser of the Central Bank of Iraq, and Dr Ibrahim Badran, under-secretary of the Ministry of

Industry and Trade for Jordan. IA. Iraq First Rejects then Accepts a $1.6 Billion Oil For Food Deal

(Back to Top)

On 4 February 1992 the Iraqi ambassador to the UN, Abdul Amir al-Anbari, declared that Iraq would not resume talks on possible oil sales: 'We decided that the talks were no longer useful or productive given the conditions imposed by Security Council resolution 706, which renders the production of Iraq oil a non-profitable enterprise and the Iraqi oil non-marketable.' However, by the end of March, agreement had been reached between the UN and the Iraqi authorities on the terms that would govern the resumption of Iraqi oil sales. Such agreement came too late to save many thousands of Iraqi deaths: a senior Iraqi health official, Abdul Jabbar Abdul Abbas, reported that in the first four months of 1992 the UN economic sanctions had caused nearly 41,000 deaths, including 14,000 child fatalities. And UN officials estimated ,that nearly five million children in the Middle East would spend their formitive years in deprived circumstances as a result of the Gulf crisis. On 3 September 1992 Britian ruled out any attempt to interfere with the aerial exclusion zone over southern Iraq. A few weaks later, the Harvard research team published their estimate that 46,900 children under the agve of five died in Iraq between January and August 1991 as an indirect result of the boming, the civilian uprisings and the UN economic embargo.

II. Embargo Drastically Affecting Iraq - 1992 (Back to Top)

Iraq, claiming purely humanitarian motives, made frequent requests for an easing of sanctions. Thus in November 1992, for example, Tariq Aziz visited New York to ask the UN to relax the current restrictions, but the Security Council issued a statement saying that Iraq had only partially complied with UN demands and so there could be no relaxation of sanctions. It was now clear that the comprehensive embargo was drastically affecting every aspect of Iraqi life. There were serious and worsening shortages of food, medicines and the spare parts needed to repair the national infrastructure (sewage plant, hospitals, water purification systems and the like). Before the war children were given government-supplied meals at school but this was no longer possible; and the embargo, extensive enough to cover imports of paper, meant that newspapers were reducing their number of pages and editions, and that the book trade had virtually collapsed, massively hampering education at all levels. Ian Katz, reporting for The Guardian (29 January 1993), describes how the resilient lraqi people are struggling to cope with appalling difficulties: thousands of engineers and doctors are unemployed, a pharmacist tells how she can only service a quarter of the prescriptions brought to her, a dentist describes how she cannot any longer obtain the necessary anaesthetics. And there is there is the frequent rsuggestion that the repression by Saddam's regime is a lesser evil than Iraq's constant humiliation at the hands of the West.

The West, for the most part, continued to pay little attention to the privations brought to the Iraqi people by the seemingly permanent sanctions. Hugh Stephens, the co-ordinator for the unofficial British Commission of Inquiry for the International War Crimes Tribunal, noted (in The Independent, 15 February 1993): 'Iraq is inhabited not only by its president, but by 18 million people who, in systematic contravention of Article 54 of the 1977 Geneva Protocols, are being subjected to hunger as a means of war, are being deprived of essential medical supplies and are facing the destruction of services essential to civilian life.' There were few signs that the bulk of the Iraqi people were blaming such privations on Saddam.

III. MAI 1993 Report(January and February) (Back to Top)

The various aid agencies and UN-linked bodies continued to report the 'devastating impact of sanctions that had no justification in law or natural justice. To most independent observers the defacto (if not de jure) blocking of shipments of foodstuffs and medical supplies to an increasingly desperate population had nothing to do with alleged Iraqi violations of UN resolutions and everything to do with Washington's strategic and economic calculations in the context of Gulf oil. Now no-one had an excuse for not acknowledging the impact of the US-contrived sanctions. For example, the charity Medical Aid for Iraq (MAI), struggling to supply medicines and medical equipment to Iraqi hospitals, was publishing regular reports. One of these (relating to the delivery of medical supplies during January and February 1993) recorded the impression of MAI aid workers that the medical situation had worsened since the last visit (May 1992); and the observation that 'as always, it has been the children who have been hit the hardest'. The deteriorating situation was plain enough:

The need in the hospitals is greater, with basic supplies such as cotton wool, dressings and soap being in desperately short supply... Shortages of milk powder, cannulae, antibiotics and syringes have been a problem since the Gulf War... now a lack of insulin has become a major problem · .. As a result children with diabetes are arriving at hospitals in comas and dying... foods containing protein are too expensive to buy. The result is an ever increasing number of children with kwashiorkor... In every hospital visited the children's wards were full of malnourished children, many of whom also have chest infections or gastroenteritis. Everyone seemed to know someone who had died recently due to lack of food or medicines.

By any medical or health index a mounting disaster was afflicting the entire country. The growing number of malnourished pregnant women was resulting in an increasing number of premature births. Asthmatic children were dying because the supplies of salbutamol had long since been exhausted. In some hospitals, with syringes and cannulae being reused, there were no protein foods and no antiseptics. At the time of the MAI visit Dr Saad A1 Tibowi, the director of the Samawa Children's and Obstetrics Hospital in southern Iraq, had given his own blood three times in the previous week· The situation was the same in all the hospitals visited: in Karbala Children's Hospital, Nassiriya Children' s and Obstetrics Hospital, Kut General Hospital, Basra Teaching Hospital, the Baghdad Medical City Children's Hospital, the Alwiyah Children's Hospital , and others. Shortages of staff and supplies, a growing incidence of kwashiorkor and other nutritional deficiency diseases, a growing incidence of typhoid, the highest recorded incidence of measles and mumps (with all 'childhood diseases potentially fatal because immunity is low due to malnutrition), a growing incidence of rickets, diarrhoea, hepatitus A, polio and diptheria, children dying of the blood disease thalassaemia because the hospitals had run out of the drug desferal, a growing incidence of marasmus - all brought about by UN sanctions in violation of the Geneva Convention·

IIIA. Harvard Expert for UNICEF Reports on Iraq (June 1993) (Back to Top)

On 22 June 1993 Shibib al-Maliki, Iraq's Justice Minister, told the UN World Human Rights Conference in Vienna that the United Nations was violating human rights by retaining sanctions: 'The people of Iraq suffer today from shortages of food, medicine and medical requirements... the blockade is causing thousands of lives to be lost among women and the elderly.' At the same time reports were appearing (The Independent, 24 June 1993) of a report prepared by Dr Eric Hoskins, a Harvard expert on public health, for the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF) on the health situation in Iraq. A 32-page 'preliminary draft' claimed to identify 'the impact of war and sanctions on Iraqi women and children'. It stated: 'Nearly three years of economic sanctions have created circumstances in Iraq where the majority of the civilian population are now living in poverty... by most accounts, the greatest threat to the health and well-being of the Iraqi people remains the difficult economic conditions created by nearly three years of internationally mandated sanctions and by the infrastructural damage wrought by the 1991 military conflict.' The conclusion to the executive summary includes the comment: ' . . . politically motivated sanctions (which are by definition imposed to create hardship) cannot be implemented in a manner which spares the vulnerable.' UNICEF, alarmed at the obvious political import of the report, decided to shelve it (Hoskins: 'I think I produced a good document').

A report (No 237, July 1993), produced by the joint FAO/WFP 'crop and food supply assessment mission' to Iraq, noted that 'pre-famine' conditions were being created: '... the nutritional status of the population continues to deteriorate at an alarming rate... large numbers Have now food ntakes lower than those of the population of African countries.' Then - two years prior to writing this update - the Mission urged 'the most urgent response from the international community to seek a solution to this crisis'. It seems that Washington is still prepared to do nothing to relieve the unremitting misery of the Iraqi people·

One irony was that the Kurds in northern Iraq, supposedly protected by the United Nations, continued to suffer under the imposition of sanctions. Thus reports (August 1993) highlighted the plight of Kurds dying in hospitals with no access to drugs. The 22-year-old Runak Kamal, admitted to Arbil Hospital, died 10 days after graduating top of her class at Arbil University: there were no drugs for the minor infection that ended her life. Dr Chalak Barzingi, of the 400-bed hospital, commented that cholera was expected and that 'we have no intravenous fluids'. This was not, he declared, 'medicine in the 20th century'. At the same time Simon Mollison, of the Save the Children charity, noted the 'collapsing situation' (The Independent on Sunday, London, 22 August 1993).

On 1 September Tariq Aziz, the Iraqi deputy prime minister, appealed yet again for the UN Security Council to lift the sanctions against Iraq - to no effect. Now it was being reported that more than 300,000 Iraqis had died as a result of medical shortages caused by the UN blockade . The Iraqi health minister, Umeed Madhat Mubarak, announced that 4000 children under five were dying each month, compared with 700 a month before the Gulf War; with deaths of people over five having risen from 1800 to 6500 a month: 'There are so many infectious diseases now which we have managed to eradicate. Now we are detecting a large amount of polio and cholera. We are now seeing so many newly detected cases of serious infectious diseases which are not just caused by the lack of medical equipment and drugs but also by general sanitation conditions.' Nearly 1000 cases of cholera, wiped out before 1990, had so far been reported in 1993.

IIIB. 1993 MAI Report (September and October) (Back to Top)

A new MAI report (for the period September and October 1993) noted rocketing food prices, the growing incidence of malnourished children, diarrhoea and gastroenteritis that were 'rife', the block on medical literature to Iraq, the continuing sharp deterioration of the health facilities , many more cases of aplastic anaemia (associated with chemical pollution), and an increase in cancers, especially leukaemia, among the children. One cited example among many was a cancer ward (in the Baghdad Medical City Children's Hospital) 'full of dying children because of a lack of basic antibiotics and cytotoxic drugs'. At the same time there was an unprecedented upsurge of referrals of children with cancer. Similarly there were many more cases of meningitis.

The tubing for resuscitaires in the City Children's Hospital were 'black with dirt, because of the shortage of cleaning and disinfecting fluids'. The labour ward was dirty ('there is little soap or disinfectant'). There were no sheets, and so women were forced to give birth 'on hard plastic tables'. The last working blood gas machine in the hospital had broken and there were no spare parts: so children could 'no longer be ventilated'.

The same sorts of problems existed in all the hospitals visited. Frequently there was no oxygen for emergencies as there were no spare parts to repair the cylinders. In one hospital supplies of catgut and silk had been exhausted: after one emergency caesarian section a woman 'had to be left open on the operating table for several hours while a member of staff went to fetch thread from another hospital'. The MAI workers saw a child dying from hydrocephaly: the intracranial shunts that would have saved his life were unobtainable. The conditions described for Najaf Children's and Obstetrics Hospital obtained throughout the Iraqi medical system:

Aplastic anaemia, usually rarely seen, is now relatively common. The hospital is also seeing an increase in premature births and congenital abnormalities ... There are many more children with leukaemia... Infections are a major problem... The hospital was short of salbutamol, and had no vitamin D injection to treat rickets... The obstetric department needs gloves, anaesthetics, muscle relaxant and catgut. They have sometimes been unable to perform emergency caesarian sections. The labour ward is very dirty, due to a lack of cleaning solutions and disinfectants... Babies cannot be ventilated; there is no blood gas machine. Many are left to die..'

IV. Conditions Worsen in 1994 with Commerical Interests Provoking Pressure to Ease Sanctions (Back to Top)

By 1994 it was clear that any consensus in the so-called international community regarding UN sanctions on Iraq was breaking down. In the Security Council France and Russia were increasingly uneasy about the blockade, not obviously for any humanitarian reason but because they saw commercial advantage in a relaxation of the sanctions regime. Turkey, not a Council member but a strategically important NATO state, was also urging a change in sanctions policy; in particular because Ankara feared the creation of an independent Kurdistan in nothern Iraq that could only serve to strenghten the dissident Kurdish minority in Turkey. Thus Douglas Hurd, the British Foreign Secretary, went to Ankara on 18 January 1994 to tell the Turkish leaders that sanctions must be maintained. At the same time a mission sponsored by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies was collecting further evidence about the plight of the Iraqi people.

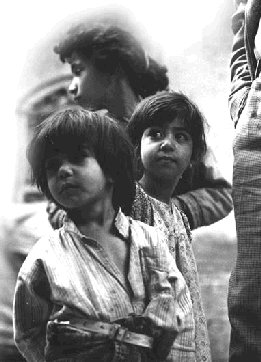

Doctors attempted in vain to save this Iraqi child who died from complications of

malnutrtion.

Doctors attempted in vain to save this Iraqi child who died from complications of

malnutrtion.

|

The new report made dismal if, by now, familiar reading. This publication's Executive Summary includes the observations:

The shortage of food in Iraq, the deterioration of the health care system and the hyper inflation has impoverished the majority of the Iraqi population...

The government rationing system provides only half of the pre-war caloric ration. Most families cannot afford the other 50%. Animal proteins are missing in most diets.

The nutritional status of children has been badly affected. Marasmus and kwashiorkor are on the increase.

Provision of safe water and sanitation are badly affected by lack of chemicals , spare parts and maintenance for pumps and generators... The deterioration of the environmental conditions is also reflected in the emergence of diseases once thought to have been eradicated, such as malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, tuberculosis.

Shortage of drugs, disposables, laboratory agents, maintenance and spare parts have reduced significantly the capacity of the health care facilities to diagnose and to provide adequate treatment.

The magnitidue of the needs to be addressed is far beyond the resources of all the aid organizations combined.

IVA. MAI 1994 Report (March) (Back to Top)

A mother tending her sick child

A mother tending her sick child

(Click to Enlarge) |

In mid-March 1994, as the Security Council moved to its routine renewal of the sanctions regime, Russia again proposed that the oil embargo be lifted. Baghdad had complied with UN weapons-monitoring demands and now Moscow wanted 'a positive decision' on the embargo question to 'allow us to begin recovering Iraqi debts' (one estimate suggested that Baghdad owed Russia £4 billion, a debt incurred for Soviet-era arms purchases). Britain and the United States predictably resisted the Russian proposals. Said one British official: 'Our view is that the Iraqis respond to a tough line and they have started co-operating because of that line. The argument that we should respond and show flexibility is specious because that isn't what has secured the positive result so far.' Now British sources were expressing irritation with France for allowing the Total and Elf Aquitaine oil companies to hold talks in Iraq about possible future investments. This, reckoned London, was an unhelpful signal to Saddam at a time when firmness was needed. On 18 March the Security Council yet again renewed the punitive sanctions: in existence, so far, for well over three years. A further MAI report (for the period 3-22 April 1994) provided yet more evidence of the worsening plight of the Iraqi people. MAI workers 'were particularly struck by the sharp deterioration of the health provision within Baghdad'; children with diabetes, epilepsy and asthma, for example, were not receiving medication; at the Karbala Children's Hospital conditions had 'worsened considerably'; at the Samawa Children's and Obstetric Hospital conditions were 'deteriorating'; the Children's Hospital in Baghdad had 'no painkillers of any kind'; and so on and so forth. As London and Washington were keen to emphasise, it was important to be firm with Iraq.

An Iraqi mother holds her sick baby.

(Click to Enlarge)

An Iraqi mother holds her sick baby.

(Click to Enlarge)

|

Now it was being reported (The Guardian, 9 May 1994) that medical journals sent to Iraqi hospitals and doctors were being impounded by British Customs and the Post Office as a breach of UN sanctions, despite repeated government assertions that medical -related supplies were exempt. Thus copies of the British Medical Journal requested by Iraqi specialists were being returned by the Post Office to the British Medical Association, even when paid for by British residents in Iraq. Dr Stella Lowry, head of the BMA's international department, had reportedly told an Iraqi doctor working in London that commercial mail, including medical journals, was being blocked. George Galloway, a Labour Member of Parliament, wrote to Prime Minister John Major to denounce this policy as a 'flagrant and disgraceful breach of UN Resolution 661: the ban on exports to Iraq does not include supplies intended strictly for medical purposes'. On 17 May the United States and Britain again withstood the mounting pressure within the Security Council for a relaxation of the sanctions regime.

In August France and Russia were again reportedly urging the Council to ease sanctions in acknowledgement of Iraq's co-operation with the UN weapons inspectors. There were moreover perceived advantages in dealing with Saddam Hussein if no realistic successor could be identified . Said one French diplomat: 'It is a case of better the devil you know.' Washington and Paris had , diplomats claimed, exchanged angry messages over the sanctions issue. Russia, supporting the French line, had reportedly reached agreement with Baghdad on the reconstruction of the Iraqi oil fields: according to sources in Russia's foreign trade ministry the work would involve £1.5 billion of contracts for three Iraqi oil fields. Moscow was also said to be supporting a controversial Turkish plan to flush a disused oil pipeline in preparation for a resumption of Iraqi oil exports. On 28 August 1994, at a joint press conference in the Jordanian capital Amman, President Suleiman Demirel of Turkey and King Hussein of Jordan called for an easing of the UN sanctions against Iraq. Now it was being reported (The Daily Telegraph, 29 August 1994) that various other countries - including Germany, Pakistan and Egypt - were also supporting a relaxation in the sanctions regime. Britain and the United States, with support from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, continued to resist any such move. In late September Baghdad announced that the already totally inadequate rations of cheap flour, rice and cooking oil had been reduced by a half.

IVB. 1994 MAI Report (October) (Back to Top)

A fly crawls on the face of 19-month-old Ahiam Fazel, one of the many

malnourished youngsters at Al Mansour Hospital.

A fly crawls on the face of 19-month-old Ahiam Fazel, one of the many

malnourished youngsters at Al Mansour Hospital.

(Click to Enlarge) |

An MAI report (for October 1994) confirmed further deterioration in the condition of the Iraqi people: 'The situation has deteriorated sharply in the six months since MAI' s last visit.., The major concern of most Iraqis is the question of how to feed their families . . . A severe deterioration is detectable in all the hospitals visited by MAI... further deterioration had been hard to imagine . . . Basic medicines and equipment are missing, while the numbers of sick and realnourished children continue to rise. The result is a deepening crisis which affects not only the present, but also the future... ' On 13 October, as part of a new package of measures negotiated by Russia, Iraq agreed to recognise Kuwait. The Russian foreign minister Andrei Kozyrev then proposed, in view of this development, that sanctions on Iraq be lifted in six months' time. But the United States and Britain continued to resist any change in the sanctions regime. Said Sir David Hannay, Britain's UN ambassador: 'One thing, however, is clear and that is the continued presence of Saddam Hussein as president of Iraq makes these questions [concerning a possible Iraqi threat to its neighbours] too difficult to answer satisfactorily.' Now, far from moving to ease the punishment of the Iraqi people, Washington was threatening the prospect of further military action against Iraq (The Guardian, 18 October 1994). The overthrow of Saddaam was now the explicit USFUK condition, without any justification in UN resolutions or international law, for the easing of sanctions.

V. 1995 Review of Sanctions saw no change in UN (or should I say US) Policy (Back to Top)

On 12 January 1995 the United States, at the Security Council's regular 60-day review of the sanctions regime, was reportedly standing firm against any relaxation in the Council's punitive posture on Iraq. Now there were some signs that Britain was 'more reluctant... to acquiesce in a widening rift with France and Russia over policy towards Saddam Hussein' (The Guardian, 12 January 1995). Tariq Aziz, Iraq's deputy prime minister, was continuing to insist that sanctions should be lifted: 'Iraq has implemented the major requirements which were set in the UN resolutions. According to the letter and spirit of the... resolutions, the Security Council has to act positively towards Iraq.' In response, Madeleine Albright, US ambassador to the United Nations, was circulating data and photographs purporting to show that Iraq had kept items of military equipment stolen from Kuwait. France and Russia had struggled to secure a statement acknowledging Iraq's co-operation with the UN special commission destroying and monitoring Baghdad's weapons of mass destruction. Britain was seemingly 'prepared for the first time to accept such a statement and is sharply aware of the mounting international pressure over sanctions.' When Washington refused to budge, Britain characteristically and supinely fell in line: sanctions would remain. Now UN sources were admitting that Iraq could only be persuaded to continue co-operating with the United Nations if Baghdad saw 'some light at the end of the sanctions tunnel'. Washington had barely acknowledged Iraq's important initiative in offering a formal recognition of the territory and sovereignty of Kuwait: Saddam - and by implication the Iraqi people - would be granted no relief until a 'long-term pattern of compliance' had been demonstrated. How long is long-term?

Now there was growing acknowledgement that the sanctions could not be maintained for ever. As a new 60-day review of sanctions approached, Madeleine Albright was finding it necessary to pressure various countries with Security Council seats at that time - Oman, the Czech Republic, Italy, Argentina and Honduras - to fall in line: Washington was finding it increasingly uncomfortable to use its veto (to prevent the lifting of sanctions) in an increasingly unsympathetic Council atmosphere. Said one UN official: 'Everyone is starting to look beyond the March review because there is the expectation that soon we will be entering a new phase.' In the event the United States and Britain stood 'shoulder to shoulder' (Albright) in resisting any change to the sanctions regime, with a British Foreign Office spokesman commenting that the leopard had 'not changed its spots'; it was 'pressure' that had 'got us to where we are now and it needs to be maintained'.

The review of sanctions by the Security Council in March 1995 saw no change in UN policy.

The toll of dying children in Iraqi hospitals would continue to mount. The holocaust would go on.

VI. 1979 - 1999, UNICEF Countrywide Child and Maternal Mortality Survey

(Back to Top)

The purpose of the 1999 Iraq Child and Maternal

Mortality Survey is to measure the levels and trends of child

mortality over the past 20 years (1979-1999).

Child mortality is a critical measure of the

well being of children. Immediately after the

gulf conflict an International Study Team carried

out an extensive Iraq-wide mortality and

nutrition survey. The findings from this survey

showed a three-fold increase in under-five

mortality from before the conflict to the first half

of 1991. However, since 1991 there has been no

countrywide child mortality survey, and the

subsequent mortality level has been the source of

considerable speculation over the last few years.

Recent malnutrition surveys in Iraq have

shown that the adverse underweight level of

under-five children has increased two-fold since

1991. Since an increase in malnutrition is

usually associated with increased child

mortality, it is likely that mortality has also

increased. Infant mortality rate (IMR)

the probability of dying between birth and exact age one year

Under-five mortality rate (U5MR)

the probability of dying between birth and exact age five

| Year | U5MR | IMR |

| 1960 | 171 | 117 |

| 1970 | 127 | 90 |

| 1980 | 83 | 63 |

| 1990 | 50 | 40 |

| 1995 | 117 | 98 |

| 1998 | 125 | 103 |

The Survey found that both the infant mortality rate (IMR) and the under-five mortality rate (U5MR) consistently show a major increase in mortality over the 10 years preceding the survey (1989-99). More specifically the results show that IMR has increased from 47 deaths per 1000 live births for the period 1984-89, to 108 deaths per 1000 live births for the period 1994-99. U5MR has increased over the same time period from 56 deaths per 1000 live births to 131 deaths per 1000 live births. These mortality results show a more than two-fold increase over a ten year time span.

Although the rate of maternal mortality may appear low at 1 per 2,000 women-years of exposure, the proportion of maternal deaths (31percent) shows that maternal mortality is a leading cause of deaths in the last ten years among women of reproductive age.

"We are on the point of no return in Iraq. More and more people spend their whole day struggling to find food for survival. The social fabric of the nation is disintegrating. People have exhausted their ability to cope." - Dieter Hannush UN World Food Program Emergency Support Officer

This appalling situation was not the result of natural disaster. Instead it represented a US-contrived genocide, a silent holocaust, perpetrated via the mechanism of a UN blockade in violation of the Geneva Convention (Protocol 1, Article 54: 'Starvation of civilians as a method of warfare is prohibited'). This is the stark face of US strategy as Washington refuses to pay its UN dues ($1.4 billion owing - 1996 estimate) but continues to manipulate the Security Council in the interest of US foreign policy.

Articles

see article index