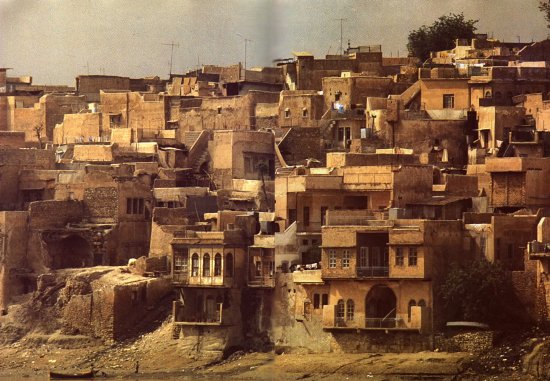

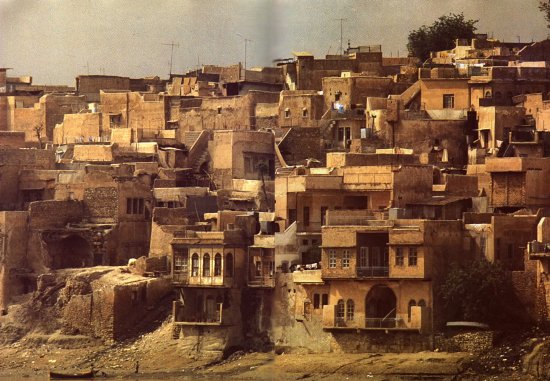

Houses in Old Mosul

(click to enlarge)

Mosul

The following is a description of Mosul as recollected by Gavin Young from his book "IRAQ Land of Two Rivers."

'There is nothing worth a Man's sight in Moussul, the place being only considerable for the great concourse of Merchants.. .' So wrote the French nobleman and traveler, J. B. Tavernier, in 1638. He added sourly, 'Only two scurvy Inns in Moussul'- and went off and grumpily pitched his tent in the Great Marketplace.

Harsh words for what is now Iraq's third largest city and sometimes described as the Pearl of the North. Tavernier reported that south of Mosul, 'we shot off our Muskets often in the night to scare the Lions'. So lack of sleep may have put him in bad humor. There are no lions there now- more's the pity. All you see on your way from Hatra to Mosul, past the spa of Hammam Ali and (a few kilometres east) the ruined Assyrian city of Assur, is a spreading greenness and, if it is the spring festival of Nawruz, the women of the north skipping about the fields in their holiday dresses of every vivid color from turquoise to orange. But Mosul seldom impressed foreign visitors very favorably in those days of the Turkish Empire. In the seventeenth century its walls were said to be imposing, but they encircled deplorably seedy buildings and filthy streets. The manufacture of the famous cloth that came from here and was called 'muslin' (mosalin) after the name Mosul, had nearly disappeared. Things were very unsettled. There was a garrison of about three thousand Janissaries and cavalry, but this was hardly enough to curb the marauding Kurdish tribes and Bedu, or the aggressive Yazidis of the Jebel Sinjar further north. On top of this troubling insecurity, the people of the Mosul region were regularly plagued by droughts and locusts.

Houses in Old Mosul (click to enlarge) |

Today your first sight of Mosul from the south is still a bit disappointing: the buildings are modern and have a utilitarian look, Yet, nearer, you can cheer up. You begin to see better things: the river and the comiche and the old houses that still stand on the water's edge, and the parks. Also you can see minarets and church spires and domes above the rooftops. Mosul improves the closer you get to it.

An early nineteenth-century visitor, J. S. Buckingham, thought the people looked interesting:

'In the people of Mosul, I thought I could observe a cast of countenance, sufficiently peculiar to mark them as a race nearly allied to, and long settled and intermixed with each other. The shape of the face is rounder than that of either Arabs or Turks . . '

Many of the people of Mosul and its environs are Assyrians. Though they are not the Assyrians of old these modern Assyrians may easily have traces of ancient Assyrian blood in their veins. They came originally from the Jebel-the mountains of the north-west- and they speak Aramaic together, the language that superceded Ancient Assyrian and was the lingua franca of the Persian Empire. (Naturally, everybody in Mosul, as anywhere else in Iraq, also speaks the first language of their country, Arabic. )

Buckingham wrote that in Mosul 'the Christians are estimated: of Chaldeans of both descriptions, one of which differs little from the Catholics, there are thought to be a thousand families; of Syrians, five hundred'. The population as a whole was 'thought by the people of the place to exceed a hundred thousand; but I should think.. . that it was even less than half that number'. That doesn't sound much of a population for a seemingly flourishing .city. For by 1800 Mosul contained a foreign resident population that included French Carmelites (French and Italian religious orders were well represented), Greek bankers and Venetian merchants. British officers of the East India Company passed through on their way from India to London on leave. Tartar dispatched riders galloped their stocky horses northwards, carrying diplomatic mail to Istanbul; camels transported ordinary mail through Mosul and Aleppo to the Mediterranean. From Basra in the deep south boats brought satin and velvet from France, English cloth, German metal goods, glass from Vienna and Bohemia, and sugar from America.

There are more Christians, proportionately, in Mosul than in any other Iraqi city. That has long been the case. Their villages cover the low hills to the north of the city and their monasteries crouch like indestructible sanctuaries high up on sheer mountain-sides. One of Mosul's troubles in the past was the unending feuding between the Christian sects and the important Christian families in the city, although that has long since given way to completely peaceful co-existence.

Naturally, as elsewhere, the city was the ball in the long drawn out game of political and military tennis between Turks and Persians. The tournament reached something of a new height of drama as far as Mosul was concerned in 1743 during the famous siege of the city by Nadir Shah. His army had already reduced Kirkuk and Quesanjak which, like numerous other towns of their size, were then independent or semi-independent. Now the Persians moved on Mosul.

The defense of Mosul was brilliantly organized by Haji Husain Pasha, who made sure that every wall was reinforced and every granary filled. Loopholes were punched through the walls and trenches dug by the time the great Nadir Shah launched his men at twelve points. His two hundred cannons 'darkened the sky by day, lighting it at night as with meteors'. Many defenders were killed; the walls were breached. The Persians burrowed under the walls and then tried to blow them up: they tottered and sagged but failed to collapse: the attack was held. And in the end Nadir Shah had to give up. The story comes to a pleasant conclusion with Nadir Shah sending emissaries with presents for Haj i Husain who responded by sending him the finest Arab mare. Whereupon Nadir Shah left the bruised walls of Mosul, mounted the mare and rode away.

Mosul is lucky to have had plenty of building materials close at hand: there was never any shortage of lime, stone and timber. A visitor to Mosul in the 1920s rightly commented that 'standing in Nineveh Street, bordered by solid, well-designed houses, their windows protected by grills, their archways and facings of marble, it is easy to imagine oneself in Italy'- a flattering remark, but Mosul today has such charm. So have its inhabitants.

Wandering about the center of the city you will find no shortage of willing guides. You need someone to help you in the tortuous but romantic backstreets of the old part of Mosul. Its ancient churches are often hidden and their entrances in thick wails are not easy to find. Some of them have suffered from overmuch restoration. The oldest church- Chamoun al Safa-dates from the thirteenth century and has a most devious approach. It also has a deep underground courtyard and a cemetery between high walls containing some ornate tombstones of Moslawi merchants. The Syrian Orthodox Church- Ma Toma (St, Thomas)- is another one with a deceptive It stands solidly but almost undetectable behind enormously thick walls and is lavishly, even gaudily, decorated.

Inside dozens of bulbs produce a blaze of electric light. The altar-cross the altar-steps are nearly as bright as a film-set. There are painted in Arabic, an old Bible in Syriac on a lectern and a lime-green with dark blue borders. And, on one wall, a small illuminated and lass-fronted pigeon-hole in which are displayed the relics of St. Thomas above your head complicated chandeliers dazzle the eye. Luckily, the church equipped with electric fans and modern heaters. Mosul's summers are hot and the winter evenings bitterly cold.

Across the broad cemetery at the back is the high stone wall with round windows of the Syrian Catholic Church. And in the cemetery itself, among other graves, the graves of two airmen stand out: one of them died in the time of the monarchy, so his wings are topped by a crown; the other followed during the present republic and his wings therefore support the symbol of a flaming sun. There are other churches in Mosul. And, of course, there are mosques. The oldest mosque is the Al Kabir, the Great Mosque, built in 172. It was built by Nur-ad-Din esh Shahid; ibn Battuta found a marble fountain there and a mihrab (the niche that indicates the direction of Mecca) with a Kufic inscripti6n. Next door is a fine brick minaret that leans like the Tower of Pisa. It is all that is left of an Ommayad mosque AD 640.

Mosul needs to be wandered about in. There are old houses here of beauty. The markets are particularly interesting not simply for themselves alone but for the mixture of types who jostle there - Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians and Turcomans.

Claudius Rich mentions the public sports of the region in the early nineteenth century: wrestling, and dog: and partridge-fights. ('The best partridges must be taken in the nest, and trained up. On that day are to fight, they are kept hungry. In the summer they must be taken to mountains, otherwise they lose their spirit . . .'). Partridge fighting to have died out. But it is certainly true that in the boiling summer even the people of Mosul tend to lose their spirits in the heat- and, fighting partridges of old, they too take to the mountains. Mosul is a center for the tourist resorts of northern Iraq.

Bibliography: