Eventually, the series of mysteries -- 11 full-weekend events and a special dinner-only case -- ran the same gamut as the original stories, from hideous murder to plots that turned out to involve no crime at all. In fact, some of the weekends at the onset did not even involve a case, and began with Holmes and Watson arriving at the Villa simply for a "rest," although the action always would heat up within a few hours -- again, in keeping with the original Conan Doyle stories.

For that reason, Sherwood said, he was reluctant to advertise the events as "murder-mystery weekends," because in many cases there was no murder, or even the suggestion of one.

"That was one of the cliches of this genre that we wanted to avoid," Sherwood said. "Another was that a 'mystery weekend' was a fun-and-games sort of frivolity. Naturally, we regarded it as an entertainment, but for us -- and for most of our guests -- it was a downright serious diversion that meant making a personal effort, something like going rock-climbing. The payoff was stretching some muscles one normally doesn't get a chance to flex, in this case cerebral."

Sherwood said that led him to create storylines for the mysteries that visitors wouldn't expect -- plots that provided subtle clues within blatant ones, and plots within plots -- sometimes forcing guests to put themselves at the forefront of their adventure and compel them to take action on their own.

"Some of them adopted disguises, or they would deceive other visitors by creating distractions," Sherwood said. "At times, the entire group of guests would end up out in the cemetery in the middle of the night, confronting a suspect. Or we might enter a building in the village surreptitiously. Other times, just two or three people had figured out what to do, while the others were completely in the dark. Then I would allow those two or three to lead the others to the places where they'd discovered the information.

"Certainly there were rules that they had to follow, but there was room for a lot of inventiveness within those rules. Some of them took the cue and created real adventures for themselves, by surreptitiously following suspects, doing their own surveillance work, crawling under the gazebo without anyone seeing them or by breaking and entering certain rooms -- only if Holmes gave his permission, of course."

Fortunately, Conan Doyle gave Holmes a commanding personality that Sherwood wielded cautiously. It was difficult at times to portray the character accurately without offending some sensitivities.

"I had a standard line when I praised one of the female guests. I would say, 'That was extremely well thought-out -- for a woman.' It was utterly in keeping for a Victorian man to say, particularly one who took such a dim view of women, as Conan Doyle drew him. Every time, the woman to whom I was speaking would take it in the humorous vein in which it was intended. But on one occasion, one of the other women who overheard me didn't care for it -- and told me so at rather heated length. After awhile, I suggested to her that, 'I cannot be anything other than what I am.' I'm not certain that she realized that she was trying to change the mind of a fictional character."

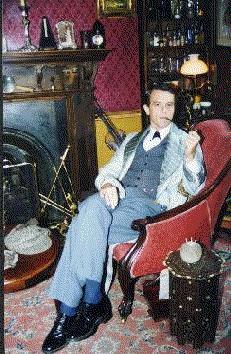

The decision to allow Sherwood's Holmes to smoke in a non-smoking establishment proved to be the stepping-stone to a blistering line that Sherwood would repeat most often in the years ahead. On almost every visit to the Villa, Holmes would be approached by a novice guest who would admonish, "There's no smoking here, Sherlock." The response typically was a withering glare and an icy answer: "Is that so? You may address me as 'Mr. Holmes.' "

221B Baker Street - Visit the Sherlock Holmes Museum in London

Go to John Sherwood's performance credits.

Since April 1997, we have had this many visitors: