These books can be purchased aboard the ship.

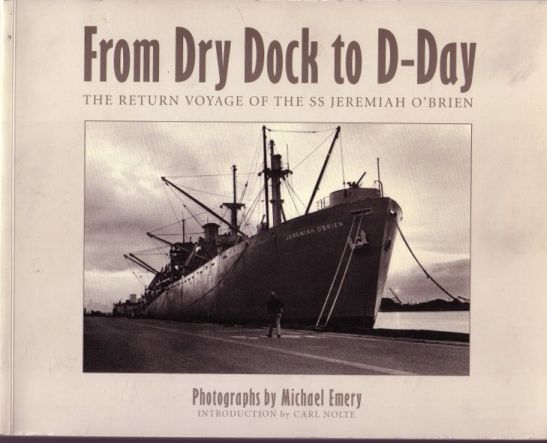

From Dry Dock to D-Day By Michael Emery Lens Boy Press, P.O. Box 460098, San Francisco, CA 94146-0098; 124 pages; $23.95 paperback

____________________________________________________

It was just last spring that Northern California readers thrilled to the incredible voyage of the SS Jeremiah O'Brien through dispatches sent from ship's deck by Chronicle reporter Carl Nolte.

Now, thanks to the stark immediacy of San Francisco photographer Michael Emery's black-and- white pictures, along with a stirring introduction by Nolte, we can get our sea legs as the old ship rocks underneath us in ``From Dry Dock to D-Day,'' Emery's photographic record of the O'Brien's five-month odyssey from San Francisco to France and back.

One of the first pictures gazes up at the O'Brien's giant underbelly from the perspective of Admiral Thomas Patterson, who saved the ship from destruction (``sometimes by losing the orders (to destroy it), sometimes by `hiding' the ship,'' as Nolte explains).

Looking at this photo, it's impossible not to feel awed by the O'Brien's story: Of the 2,751 Liberty ships constructed during World War II -- each one hastily built ``to be expendable, good for a single voyage, or five years at the outside,'' Nolte reminds us -- only the O'Brien survived for a half-century, and not just as part of the old mothball fleet in Suisun Bay or as a tourist attraction in San Francisco.

Of the 5,000 ships that landed at Normandy on D-Day, the O'Brien was the only vessel to return on the same day 50 years later. That it was sailed on its return voyage by a crew whose ages ranged from about 70 to 90 still sends chills up the spine.

``A lot of people said it could never be done,'' Nolte writes. ``The aged ship would crack, the engine would fail, it would be too much for the old men and they would die. `You better bring some body bags,' was the word on the waterfront.''

And yet an up-front photo of oiler Richard Hill cooling off under a light rain (temperatures in the boiler rooms could climb to 140 degrees, Emery tells us) while Patterson checks the ship's bearings seems to tell it all.

Emery, who earned his passage by working as a deckhand (as did Nolte), has the gift of turning up everywhere, apparently unnoticed, to snap intense, deeply personal shots of faces, events, conversations and moods.

Moments of gaiety (``The Three Messmen'' singing ``Happy Birthday'' on a ship-to-shore call to a fellow crewman's 101-year-old mother-in-law) mix with rare occasions of privacy (Pat McCafferty, one of only three stewards, takes a break from ``serving 57 people three meals a day, seven days a week, for over five months'').

Routine anxiety (fireman Edgar Lingenfeld worries over the starboard boiler) mixes as well with routine claustrophobia (going to sleep in ``the racks'' looks about as much fun as getting an MRI).

It's perhaps because of an apparent absence of color in the midst of so much fog and drizzle, of iron-gray water viewed from steel-gray decks under cast-iron skies, that Emery's photos seem more immediate and authentic in black and white than they might have in color.

A CLINTON HANDSHAKE

Even as the Queen of England sails by, or President Clinton shakes hands with crew members, that grainy feel of old newspaper clippings, wartime vigilance and pure machine maintenance give these photos an urgency that belies their still-life scenes.

Faces soon begin to look like those of old friends, and when the crew dresses in uniform to march in a commemorative parade in Cherboug, France, in June 1994, we feel like cheering.

12/20/94 San Francisco Chronicle. All Rights Reserved, All Unauthorized Duplication Prohibitted.

Here, delightfully, we go again with the veteran crew of the World War II Liberty ship the Jeremiah O'Brien, steaming along on its historic voyage from San Francisco to Normandy for the 50th anniversary of D-Day.

Other books have described this incredible 18,000-mile voyage, but chief mate and maritime historian Walter Jaffee, author of the official Jeremiah O'Brien bio, ``The Last Liberty,'' provides the definitive ``trip of a lifetime'' story here. His first-person narrative brings us right on board to watch sailors -- average age 70 -- prepare for the big day, swap World War II stories and grapple with such seemingly mundane operations as changing a lightbulb.

``Not just any light bulb, but the range light, at the top of the tallest mast on the ship,'' Jaffee writes. ``Normally, a boatswain's chair is rigged and one of the sailors is hoisted up. But since we were in a Naval ship yard with cranes at every pier, it was thought the simplest thing would be to get the British Navy to lift a sailor up to the light fixture in a large bucket designed to carry people.''

Of course, nothing is simple on a 50-year-old ship that was designed to last a fraction of that time, and Jaffee lovingly presents the full details of every aspect of the journey from President Clinton's visit to beer breaks in the No. 4 hatch.

7/9/95 San Francisco Chronicle All Rights Reserved, All Unauthorized Duplication Prohibitted.

By Floyd Beaver

The Last Liberty by Walter W. Jaffee Glencannon Press P.O. Box 341, Palo Alto, Calif. 94302; 474 pages; $29.95

Had he done no more than write the story of the SS Jeremiah O'Brien - the ship that's sailing to Europe for the 50th Anniversary of D-Day - Walter W. Jaffee would have earned the appreciation of all who remember the old World War II Liberty ships (and the gratitude of those too young to remember) for the thorough and often artful way he has constructed this ship's biography.

Liberty ships were first built at the start of World War II, when German submarines were sinking Allied merchant ships faster than they could be built. Starting with a brief history of the Revolutionary War hero for whom the O'Brien was named. Jaffee recounts the history of this particular ship, from its frantic origins and wartime voyaging through the end of the war, when it was left to rot in Suisun Bay's Reserve Fleet.

For ship and World War II buffs there are pages of specifications and operating procedures, including photo copies of documents in what could be eye-glazing excess for casual readers; but are decently concentrated aft, where they do not get in th way.

Viking Customs

Jaffee drops in intriguing bits about the sea and ships in general, such as the Viking custom of crushing living slaves under the launching rollers of their ships "as an invocation to the great destruction forces of the sea" and the curious fact that the direction in which a steel ship is pointed during its construction affects its magnetic field and thus its steering compass throughout its life.

The selection of an existing British design and traditional engines simplified the problems of construction and operating with hurriedly trained landsmen, as Jaffee shows. Still, the Liberty ship program remains one of the major triumphs of the American war effort. Once in production, these 441 foot ships were produced in only 52 days, on average.

The fact that the O'brien, a product of such emergency wartime labor, is still up to a 25,000 mile voyage to the landing beaches of Normandy a half-century later, is telling evidence of American ship-building quality even under crises conditions.

Of equal interest is the way the O'Brien's voyages are detailed in terms of the daily life of the crew, right down to lists of the lowliest wiper, ordinary seaman or Navy gunner. Since Liberty ships were identical combinations of interchangeable parts, the O'brien's story also reflects that of thousands of others. (Of the more than 2,700 Liberty ships built, only 200 were lost to enemy action.)

Survivors' Memories

Salted liberally throughout the text are survivors' memories, wisely left in their own, often unschooled words, presented with telling poignancy and almost poetic eloquence. One sailor describes looking down into the engine room of a ship that was deliberately sunk off the Normandy beaches to serve as a breakwater for other vessels.

"Water was just lapping around the tops of the great cylinders of gloom below. The engine room was full of sound, not great sound, but the tiny sounds of unseen movement in the water below: faint gurgles and bubblings and occasional plops, last dying murmurs where for years there had been the steady thud, thud, thud of massive machinery..."

Old photography of surprising quality contributes a strong sense of intimacy with the crew and the times, and Jaffee does a good job explaining how the O'Brien was saved from the ship-breakers through the dedicated efforts of a few people. As the title notes, the ship is the last of its kind.

Within the limits of its field, this is an important work, amply researched and ably written. It is worth reading by sailor and armchair traveler alike.

May 3, 1994 San Francisco Chronicle. All Rights Reserved, All Unauthorized Duplication Prohibitted.

Go to Jeremiah O'Brien home page