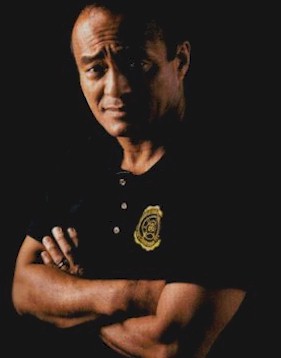

Academy of Jeet Kune Do Fighting Technology

Athens

Greece

Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Instructor

Vagelis Zorbas

World Martial Arts

Martial arts

describes bodies of codified practices or traditions of unarmed and armed

combat, often with the goal of developing both the character of the

practitioner as well as the mindful, appropriate, controlled use of bodily

force. The martial arts, due to a century of exaggerated, exotic zed

portrayals in popular media, has been inextricably bound in the Western

imagination to East Asian cultures and people, but it would be incorrect

to say the martial arts are unique to Asia. Humans have always had to

develop ways to defend themselves from attack, often without weapons, so

it would not be correct to think that unarmed combat originated from East

Asia. But what differentiates the martial arts from mere unarmed brawling

is largely this codification or standardization of practices and

traditions, many times in routines called forms (also called kata, kuen,

tao lu, or hyung), and above all, the controlled, mindful application of

force and empirical effectiveness. In this sense, boxing, fencing,

archery, and wrestling can also be considered martial arts.

Thus, the history of martial arts is both

long and universal. Martial arts likely existed in every culture, and at

all classes and levels of society, from the family unit up to small

communities, for instance, villages and even ethnic groups. One example is

tantui, a northern Chinese kicking art, often said to be practiced among

Chinese Muslims. Systems of fighting have likely been in development since

learning became transferable among humans, along with the strategies of

conflict and war.

In the West, some of the oldest written material on the subject is from

the European

1400s, and written by notable teachers like Hans Talhoffer and George Silver. Some transcripts of yet older texts have

survived, the oldest being a manuscript going by the name of I.33

and dating from the late 1200s.

In recent times, various attempts at

reviving historical martial arts have been done. One example of such historical martial arts reconstruction

is Pankration, which comes from the Greek (pan, meaning

all, kratos, meaning power or strength).

"Martial arts" was translated in

1920 in Takenobu's Japanese-English Dictionary from Japanese bu-gei or bu-jutsu that

means "the craft/accomplishment of military affairs". This definition is translated

directly from the Chinese term, wushu (Cantonese, mou seut), literally,

martial techniques, meaning all manner of Chinese martial arts.

|

Table

of contents |

|

1 Overview |

Overview

Martial Arts are, simply put, systems of

fighting. There are many styles and schools of martial arts; however, they

share a common goal - to defend oneself. Certain martial arts, such as Tai Chi Chuan may also be used to improve health and,

allegedly, the flow of 'qi'.

Not all Martial Arts were developed in Asia.

Savate,

for example, was developed as a form of Kickboxing in France.

Capoeira's

athletic movements were developed in Brazil.

Martial arts may include disciplines of striking

(i.e. Boxing,

Karate), kicking,

wrestling (Taekwondo, Kickboxing, Karate),

grappling (Judo,

Jujutsu, Wrestling), weaponry (Iaijutsu, Kendo, Kenjutsu,

Naginata-do, Jodo, Fencing), or some combination of those three (many

types of Jujutsu).

Many Asian martial arts traditions are

heavily influenced by Confucian culture. Students were traditionally

trained in a strict hierarchical system by a master instructor

("sensei" in Japanese; in Chinese "sifu", or "shifu",

lit., the master-father), who was supposed to look after your welfare, and

the student was encouraged to memorize and recite without deviation

the rules and routines of the school. Critical thinking about the

tradition was not often encouraged, merely the proper application of

techniques to controlled circumstances. In this hierarchy, those who

entered instruction before the student are considered older brothers and

sisters; those after, younger brothers and sisters. Some system of

certification is usually involved as well, where one's skills would be

tested for mastery before being allowed to study further; in some systems,

such as in kung fu, there were no certifications, only years of close

personal practice under a master, much like an apprenticeship, until the

master deemed your skills sufficient. Today, this pedagogy is rarely used.

The different styles of Asian martial arts

are sometimes divided into two major groups. There are the hard

styles like Karate

and Kickboxing which favour an aggressive offense, usually

involving striking, in order to quickly defeat an opponent. On the other

hand, there are the so-called soft styles like Judo

or Aikido

which center upon turning an opponent's force against themselves.

It is now difficult, in modern societies, to

gauge the actual effectiveness of martial arts, but among the most popular

ways of doing so throughout the Americas is through sport martial arts

tournaments, exhibitions, and competitions. These types of competitions

usually pit practitioners of one or many traditions against each other in

two areas of practice: forms and sparring. The forms section involves the

performance and interpretation of routines, either traditional or recently

invented, both unarmed and armed, judged by a panel of master-level

judges, who may or may not be of the same martial art. The sparring

section in sport martial arts usually involves a point-based system of

light to medium-contact sparring in a marked-off area where both

competitors are protected by foam padding; certain targets are prohibited,

such as face and groin, and certain techniques may be also prohibited.

Points are awarded to competitors on the solid landing of one technique.

Again, master-level judges start and stop the match, award points, and

resolve disputes. After a set number of points are scored or when the time

set for the match expires (for example, three minutes or five points), and

elimination matches occur until there is only one winner. These matches

may also be sorted by gender, weight class, level of expertise and even

age.

On the subject of competition, martial

artists vary wildly. Some arts, such as Boxing

and Muay Thai train solely for full contact matches,

whereas others like Aikido

and Krav Maga actively spurn such competitions. Some

schools believe that competition breeds better and more efficient

practitioners; others believe that the rules under which competition takes

place have removed the combat effectiveness of martial arts or encourage a

kind of practice which focuses on winning trophies, rather than the more

traditional focus, in East Asian cultures, of developing the Confucian

person, which eschews showing off (see Confucius, also Renaissance Man.)

As part of the response to sport martial

arts, new forms of competition are being held such as the Ultimate

Fighting Champions in the U.S. or Pancrase in Japan

which are also known as mixed martial arts or MMA events. While the

financial success or failure of these events is not well-known, it is

interesting to note that certain systems do indeed tend to dominate these

so-called full contact or freestyle competitions, and these styles often

are the financial sponsors of these competitions, which tends to cast

suspicion on the validity of such outcomes. Supporters of those styles

which win time and again make the statement that this proves the

real-world self defense effectiveness of their art, but it is all too easy

to manipulate the results to work in one's favor.

Some advocates of freestyle or full contact

justify their sport that in actual hand-to-hand combat the only thing that

matters is defeating the enemy. In actual combat, these advocates claim,

stylistic differences or the counting of points scored are moot. If the

primary objective in competition is to score points on your opponent, this

is not a martial art but a sport. The logical conclusion of this viewpoint

is that there is no such thing as a competition with rules, only

gladiatorial affairs resulting in death, disability, or rendering

unconscious of one or more of the participants. While this type of contest

-- for instance, the Chinese leitai-style contest, where the opponent is

not considered completely defeated until thrown off the stage -- has

traditionally been the manner in which martial arts are proven, there are

few events that maintain this attitude today.

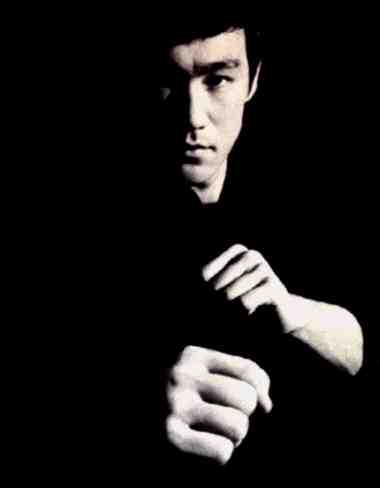

Bruce Lee, the American-born, Hong Kong-bred martial

artist and actor, was among the first in the United States, and perhaps

the most influential theorist-practitioner in martial arts history to

challenge many conservative ideas within martial arts, specifically,

combat effectiveness vs. blind recitation of forms, the fear of non-Asians

using their own art against them, and certain fundamentalist aspects of

martial arts. Although he favored the Southern Chinese art of Wing Chun, he was well-versed in a number of other

Chinese martial traditions. Arriving in the Seattle area in the 1960s, he

soon encountered styles of other martial arts, such as those practiced by

established communities of post-Internment Japanese Americans and Filipino Americans in

the Pacific Northwest. As an undergraduate philosophy student at the

University of Washington, and after graduation, he began to teach kung fu to non-Chinese. At some point, he began to

realize that even as martial arts maintained bodies of techniques,

uncritical maintenance of traditions, and rote recitation of forms

strangled combat effectiveness and dynamic response in the practice of

unarmed combat. Couching his language in Taoism

(also Daoism),

but with a kind of hard pragmatism, he sought to create a mental framework

-- "no style as style" -- focused solely on the improvement of

unarmed combat. This attitude absorbed influences from all martial arts --

Filipino armed and unarmed techniques, European and Japanese grappling,

wrestling, and fencing techniques, Korean kicking techniques, Chinese

close range hand techniques -- and were evaluated for their effectiveness.

With his untimely death however in 1973, he was unable to develop and

articulate his philosophy further, but, what he had already developed has

since been built upon by his students and colleagues and developed,

ironically, into a new style, which Lee himself named "jeet kune

do" (Cantonese, lit. way of the intercepting fist). To resolve this

contradiction, practitioners, and more specifically, teachers of jeet kune

do often maintain that what they practice is not a style or a tradition,

but concepts. Whatever the case may be, Bruce Lee left an indelible legacy

in the history of the martial arts, which has forever changed how the

martial arts are thought about and practiced.

Asian Martial Arts

- Borneo

- Burma

- China all Chinese martial arts called Kung Fu, Wushu, Ch'uan Fa or Kuntao

- Internal styles: see Nei chia

- Hsing Yi (Hsing I)

- Pakua Chuan

- Tai Chi Chuan

- Ba Gua

- External, Shaolin Quan, and combination styles:

- Black Crane Kung Fu

- Black Tiger Kung Fu

- Chin Na

- Choy Lay Fut

- Dragon Kung Fu

- Five Ancestors Kung Fu

- Go-ti Boxing

- Hung Gar

- Leopard Kung Fu

- Monkey Kung Fu

- Northern Praying

Mantis

- Pak Mei (White

Eyebrow)

- Shuai Jiao

- Snake Kung Fu

- Southern Praying

Mantis

- San Da

- San Shou

- Tiger Kung Fu

- Wing Chun

- Wing Tsun

- White Crane

- Indonesia

- Japan

- Aikido

- Aiki

Jutsu

- Bojutsu

- Bujutsu

- Dschiu Dschitsu

- Jiu Jitsu

- Jodo

- Judo

- Ju

Jitsu

- Karate

- Kenpo

- Kendo

- Kenjutsu

- Kobudo

- Kyokushin

Kai

- Kyudo

- Naginata-do

- Ninjutsu

- Ninpo

- Shintaido

- Shorinji kempo

- Sumo

- Taijutsu

- Taido

- Tanto Jutsu

- Tegumi

- Korea

- Gjogsul

- Hapkido

- Hwarang Do

- Kuk Sool Won

- Kumdo

- Soo Bahk Do

- Taekyon

- Taekwondo

- Tang Shou Dao

- Tang Soo Do

- Yudo

- Yusul

- Malaysia

- Mongolia

- Mongolian wrestling

- Thailand

- Philippines (Filipino Martial Arts or FMA)

- Arnis (see Eskrima)

- Balintawak

- Buno

- Cadena de Mano

- Combat Judo

- Doble Olisi

- Dumog

- Eskrido

- Eskrima

- Eskrima De Campo

- Espada y daga

- Estoca

- Estocado

- Filipino

Kuntao

- Gokusa

- Kadena

de Mano

- Kali

(see Eskrima)

- Kombatan

- Kuntao

- Kuntaw

- Kuntaw

Lima-Lima

- LAMECO Escrima

- Mano Mano

- Modern

Arnis

- Panandata

- Pananjakman

- Panantukan

- Pangamot

- Pangamut

- Pekiti

Tirsia Kali

- Sagasa

- Sikaran

- Suntukan

- Tat Kun Tao

- India

- But Marma Atti

- Gatka

- Kalaripayatu

- Kalari

Payit

- mallak-rida

- malla-yuddha

- niyuddha-kride

- Silambam

Nillaikalakki

- Vajra

Mushti

- Vietnam

- Cuong

Nhu

- Quan

Khi Dao

- Viet Vo Dao

- Vo Vi Nam

European Martial Arts

·

- Boxing

- ESDO

- Fencing

- Glima

- Historical fencing

- Jogo do Pau

- Leonese fighting

- Pankration

- Schwingen

- Wrestling

- England

- Cornish Wrestling

- Cumberland wrestling

- Llap-goch

- Lutte Breton

- Purring

- Westmoreland wrestling

- France

- Boxe Francaise

- Chausson

- Chausson Marseilles

- Lutte

Parisien

- Savate

- Savate-Danse

du Rue

- Germany

- Anti Terror Kampf

- Gojutedo

- Individual Fighting Concepts Mallepree

- Kenjukate

- MilNaKaDo

- Stockfechten

- Ireland

- Bata

- Collar and Elbow

- Israel

- Haganah system

- Krav Maga

- Krav Maga Maor

- Wu Wei Kung Fu

- Italy

- Caestus

- Graeco-Roman wrestling

- Scherma di daga

- Netherlands

- Amsterdams

Vechten

- Russia

- Agni

Kempo

- Armeiskii

rukopashnyi boi

- Boevoi Gopak

- Buza

- Cambo

- Combo

- Draka

- Kolo

- Kulachnoi

Boya

- ROSS

- Rukopaschnij Boj

- Russky Stil

- Russian Boxing

- Sambo (Sombo)

- Samoz

- Skobar

- Slada

- Slawjano-Goritzkaja

Borba

- Spas

- Systema

- Systema

Kadochnikowa

- UNIBOS

- Velesova Borba

- Vyhlyst

- Wjun

- Scottland

- Greenoch

- Spain

- Uzbekistan

Middle East

- Iran

- Koshti

- Wu

Wei Kung Fu

Africa

- Angola

- Capoeira d'Angola

- Egypt

- Egyptian stick fencing

- Guinee

- Kenya

- Massaļ

- Senegal

- Sudan

- Nuba fighting

- OtherAfrican Martial Arts==

- Canarian fighting

- Zulu stick fighting

- Kalindi Lyi

South American Martial Arts

North American Martial Arts

- USA

- All Style Karate

- American Combat Judo

- American Combat Sambo

- American Kempo Karate

- American Kenpo also see

Ed Parker

- Anarchist Simple Street Fighting

- Pacific Archipelago

Combatives

- Choi Kwang-Do

- Chu Fen Do

- Combat Submission Wrestling

- Dog Brothers Martial

Arts

- Dos Manos System (this

is NOT Dos Manos!)

- Full Contact Karate

- Jailhouse Rock

- Jeet Kune Do

- Jeet Kune Do Concepts

- Kickboxing

- Kajukenbo

- Marine Corps LINE

Combat System

- Natural Spirit

- Progressive Fighting

System

- SCARS

- Shoot Fighting

- Taebo

- World War Two Combatives

Misc

·

- All-Style-Do Karate

- Bajawah Boxing

- Catch-As-Catch-Can

- Combat Bujutsu

- Combat Hapkido

- Combat Ju Jutsu

- Combat Karate

- Defendo

- Defendu

- Eskimo Fighting

- Gun Kata

- Inoui Fighting

- JKD Real Combat

- Jukado

- Kalimasada

- Kali

Sikaran

- La

Lutte

- Lima

Lama

- Progressive Self

Defence System

- Savasu

- Silek

- Sport

Karate

- Street Sambo

- Taekido

- Taibo

- Thaikido

- Tidju Boxing

- Wing Kido Kai

Martial Arts Weapons

- Arnis sticks

- bow and arrow

- Yumi (Japanese longbow)

- Knife

- Nunchaku

- Quarterstaff

- Rapier

- Spear

- Sword

- Bokken or bokuto (Japanese wooden swords)

- Bolo

- Broadsword

- Iaito

- Kampilan

- Shinai (Japanese bamboo sword)

- 3 Sectional Staff

- Chain Whip