In T. Lindsey & H. O’Neill (eds.) Awas! Recent art from Indonesia. Pp. 75-84. Melbourne: Indonesian Arts Society. 1999.

On the streets of the fourth most populous nation on earth, the Suharto government cultivated a culture of fear that guaranteed the appearance of normal life (Pemberton, 1994:8). The street, as the realm of the rakyat (little people), is the ultimate space to be negotiated and fought for in the performances of power, survival, and cultural identity. The streets are where the little people sweat and toil to support the backbone of Indonesia’s economy. But their sheer numbers and potential for disrupting the performances of stability, normality, and prosperity, mean that the people must be guided. The State continually reminds the ‘little people’ that they are not yet ready to enjoy the fruits of development because they are uneducated, spontaneous, savage, and without discipline (Susanto, 1993). For their own good, and for the good of the nation, they must be controlled. Social control takes two forms, which both focus on the streets. One is coercion: the brute force of the military. The other is consent: the ideological indoctrination reinforced through monuments, slogans, banners, billboards, placards which all remind the people who is in control, and what they must do to eventually get their share.

Rakyat are central to artists’ focus also. Yet scholarly writings about art almost entirely focus on the so-called elite or high arts, the great traditions of the courts, the museums, the galleries, and five star hotel lobbies. Popular or mass art includes much of the kitsch, handicrafts, or reproductions of cultural symbols produced for the broader population and through the mass media. Folk art or the ‘little’ traditions are usually created anonymously and include functional, household items such as pottery, weavings, and children’s games, as well as masks, puppets, painting on glass, and other ‘naïve’ arts (see Fischer, 1994). Many denigrate the popular or folk traditions, as seen quite simply in the evaluative metaphors used to describe them - that is, high (and expensive) versus popular and low (and cheap). Yet intentioned interaction and borrowing between these ‘levels’ are fundamental for much of the development of modern Indonesian art. In fact, the direction of transmission is always from the ‘bottom’ to the ‘top’, from the folk to the popular to the elite, rather than the other way around (e.g. Fischer, 1994). For Indonesian artists, the search for cultural roots and identity is part of a conscious strategy of self-knowledge, which looks down to the streets for its legitimacy.

Within the periodic upheavals that have marked Indonesia’s development from colony to independent nation, and from economic tiger to a situation of unrelenting chaos and crisis, artists have asserted their social concern by borrowing from urban mass culture, specifically the street culture. Indonesian artists make their careers by condemning the immense power, wealth and greed of the elite. They reject fine art labels and the elitism and exorbitant prices of art, as they embrace the emblems of the streets: poster art, comics, installations, graffiti, street theatre, stickers, and T shirts, which are either incorporated into their work or become the end product. For artists who are really concerned for peasants and workers, street interactions become more direct through protest. Such posturings occur repeatedly in Indonesian history as a mark of concern for the desperate plight of the rakyat.

In Suharto’s Indonesia, crossing such seemingly innocent boundaries in an attempt to either ‘unite with’ or ‘speak for’ the dispossessed other was illegal. The Suharto regime maintained its order by monopolizing public discourse and imposing its brand of ‘national culture’ as a redefined version of the Javanese hierarchical order. Communication of any sort is subjected to the strictest regulations. Those who identify themselves as ‘socially aware’, seek to unite with the silent dispossessed rakyat by ‘speaking on behalf of’ them, which ironically often serves to further the distance between the ‘spokespersons’ and those spoken for. This dilemma of ‘location’ is a potent one, which requires a leap across social, political, economic, linguistic, and spatial boundaries. It often leads to tension and frustration among artists and intellectuals precisely because it involves ‘speaking for’ another, who may or may not understand, or hear, or respond (appropriately?), or even care.

The Indonesian state regarded culture as one of the areas requiring their direct and indirect guidance, and took extensive measures to make sure anything cultural did not appear to be ‘political’. Censorship, stringent authorization requirements, and surveillance are the necessary prerogatives of the state in the name of well-being and national development, on the grounds that people are not yet mature enough to handle freedom of thought and expression (Wright, 1994:161). Thus, the state aims its messages at the streets, the preferred canvas for reaching the public. The state’s version of the social realist poster is presented as huge billboards, towering over the little people and showing them what they need to know. Billboards in red and white (the national colors) insist the populace use good and correct Indonesian, limit the size of their families, pay their taxes, and obey the demands of the Authority. Images of the glorified peasant reaping an abundant harvest, the perfect family with their happy, plump, educated children, cultural diversity and unity, the benevolent kindness of the military, and other rewards for compliance with the state’s development and security policies present the population with promises for the future – if they play their roles correctly. The state’s hold over the people is a hold over their streets, where alternative voices presented in public places are silenced, white-washed, and made orderly.

The people verify their compliance to the State’s authority through the proliferation of their own signs. One such sign is the gapura (entrance portals), found at all intersections leading into villages and kampungs. The portal style is derived from Javanese antiquity, but the message is Suharto-style nationalism. These mini-monuments, with their prescriptive symbols of the state and its ideology, attest to a community-wide acceptance of the order so central to the state’s rhetoric (Lindsey, 1993). For the state’s beautiful kampung competitions, the gapura will be covered in brightly colored scenes of the revolution. But elaboration equals acquiescence to an ideology, not necessarily prosperity. Each city too must have a motto with little connection to reality sprouting across its hill tops and intersections, often in gapura style, one more of the many symbols of acquiescence required to fill public spaces.

As central as the streets are to every day life, they are off-limits for any but these most mundane of uses. The only legal exception occurs once every five years, over the four week period that erupts into a huge street spectacle: the national election campaign. But again, it is how the people use the streets that is more interesting than the election. Under the incongruous banner, the "Festival of Democracy", Suharto would run unopposed, and his Golkar party would be guaranteed 70% of the vote. In May 1998 the might of the masses reclaimed their sovereignty over the streets when they overthrew the dictator – but not his system of control. Reclaiming the streets does not mean abandoning the discourses of submission, however, and pro-reformation graffiti reflects the images and styles of the state, as idealistic slogans. In Yogyakarta, as in most cities, the pre-election street art rejected the main instrument of state control: the military (ABRI), but not the hierarchy and its systematic inequality.

The first so-called free and fair elections in 45 years were held on 7 June 1999 as expert after expert predicted riots and mass destruction. The need for state control over the ‘spontaneous and savage’ people was obviously supported by these new elites as they too expressed their fears of an ‘uncontrolled’ masses. But the lure of the streets and the pleasure it offered were more important than scholars realize. Despite the doomsday prophecies, there were carnivals as the people flocked to their streets in whatever means they could afford – private cars, rented city buses or trucks, on scooters, and on foot. Without the tamperings of political elites, people power revealed its true colors – red for Megawati Soekarnoputri’s PDI-P party. But despite the reformation, campaigns are little more than street-based entertainment and few of the parties revealed a platform, a direction, or any real differences beyond basic symbolism. Red for Mega’s PDI-P, Blue and white for Amien Rais’ Pan Party, and green for the Islamic parties. But red has always been the favorite among the young, which is clearly seen in their props, make-up, costumes, and flags some of which featured rock groups. Yet, prior to the reformation, this simple deviation from the campaign rules would not have occurred.

Indonesian young people do not need the election alone to make use of the street for its performance possibilities. An increasing number go to great lengths to break away from the imposed normality of everyday life. As elsewhere, many youths have turned again to rock music for their street fashions. School boys wear make-up at night with the recognized costumes of underground music fans. Others turn to punk or gothic styles featuring tattoos, body piercing, Mohawks, and other emblems of difference, their bodies becoming both canvas and portable gallery. These must be admired as extremely bold statements of non-conformity in a nation which periodically ordered its military to shoot to kill anyone with a tattoo.

As Suharto was approaching the end of his reign in 1998, Indonesians turned to posters, banners and graffiti to an extent that was reminiscent of the election campaigns. On all major intersections and roads, and all round campuses, the people had their say by raising the red flag with the circled R. Kampung walls were suddenly full of anti-Suharto sentiments in spraypainted letters. Some were polite: nuwun mundur mbah (we beg you to step down please grandfather) while others were less so: Go to hell ABRI (the Indonesian military). This enthusiastic use of graffiti was a logical extension to the previous appropriations of urban iconography and a celebration of the new freedom of the streets.

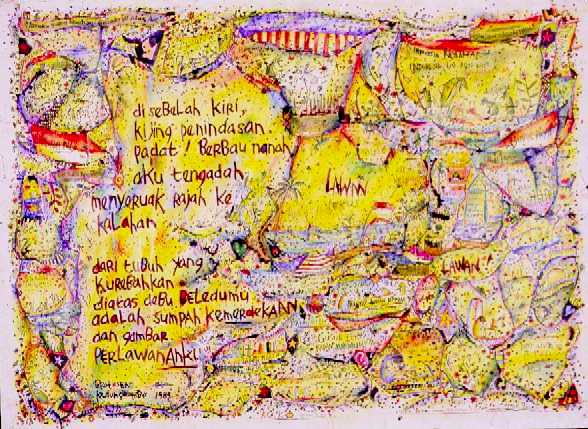

Kedong Ombo series by Athonk

‘Socially aware’ art from the late 1980s to the present is characterized by its direct link to urban street culture. One of the early Yogya artists to actively appropriated icons of popular culture was Athonk, through his colored pen and ink series of drawings called Kedung Ombo (1989-1994). In defense of the victims of this early land rights issue, which to this date has yet to be resolved, Athonk drew cartoon figures busily involved in various aspects of life: farming, fighting, eating, falling in love, being hungry, fishing, travelling, using a computer, protesting, abusing power, and talking rubbish, "bla, bla, bla, bla", all located within their own frames. Just like the comics from which he drew his inspiration, each of the mosaic-like panels contains Indonesian, Javanese and a few English words: words of oppression, words of acquiescence, words of resistance. This series also features the poetry of Brotoseno:

On the left

Crowded with the tombstones of oppression

And the stench of pus

I gaze up through the scars of defeat.

With my body

that I throw down upon your dust

I pledge my oath of freedom

And this picture of my resistance.

In 1992, the Indonesian Art Institute hosted a Student Arts Festival and featured a Visual and Experimental Arts Exhibition. Athonk entered three of these drawings. Come opening day, the committee had removed his drawings and hid them under sheets. Their reason was that the opening would be attended by government officials and military officers. When Athonk discovered his artwork was banned, he hung his drawings on the billboard in front of the entrance to the gallery as an act of protest. The censorship from within the academy points to the fear of artistic expression and clarity that existed within the art community itself. Yet a local journalist showed how clarity was strongly desired in the arts:

"....as far as experimentalism goes we can only truly understand Athonk’s Kedung Ombo. The other works....who knows?"

‘Socially aware’ art demonstrates its link to the streets through the intensity, effectiveness, and clarity of words and their role in the experience of politics, society and change. As previous generations had done, young artists, who have matured and even thrived under an oppressive regime, have responded to the challenges of surveillance and suppression through rejecting the boundaries between university-educated student and ignorant masses. Yet again, we find the artist striving to give expression to a ‘purely Indonesian’ people’s art, which they interpret as reflecting concern for the working classes. Thus, they appropriate icons of urban mass culture: comics, posters, stickers, T-shirts, and materials associated with rural poverty: soil, hay, bricks, and caping (conical bamboo hats worn by farmers). As a further ‘unifying’ strategy, many hang their artwork on gallery walls with tacks, rather than in frames and under glass. A growing number of these new artists will soon abandon the gallery altogether and exhibit on the streets, such as Athonk was forced to do after the gallery rejected him.

Other pre-reformation artists, such as S. Teddy D. present abstract figures of heads, blank, empty, yellow, and weighed down by words. The painting entitled ‘Export’ shows how manufacturing is essential for the development of the nation, and thus, the masses are required to devote all their resources and energy toward that one goal. Human figures are all emaciated, but the symbol Teddy most frequently repeats is the empty head, the psychological state required for survival. If people were to delve too deeply into their own realities, they would surely become insane.

Tony Volunteero’s work is mainly drawings on cardboard. His style of drawing is quick, cluttered, certainly not elegant, but it always demands the viewer search through its intricate forms to locate the story it tells. In these narratives of life, people appear caught in interactions which are both varied and complex, crude and very abrupt. Symbolism is ripe here and viewers must search their own understandings of reality to decipher who the faceless crowd is and why they are bound up as one. They are guarded by headless military figures; they hold aloft a masturbating officer; a fat man speaks shit into their wide open mouths; images of destruction and brain-washing, with the faceless still ignored by the king. A cartoon dog says, "You are a communist" in Javanese. This is the true history of Suharto’s Indonesia, presented through meanings or symbols no Indonesian would misunderstand.

PKI Kowe by Tony Volunteero

Yogyakarta: Post reformasi art

Since the reformation, groups of artists have returned to nationalist concerns for art that is ‘socially aware’ and proud of its roots in the revolution and poverty. With the streets now increasingly ‘liberated’ artists make use of this domain of the people to communicate directly to them. Street art movements aim to create ‘inclusivity’, while they ‘speak for’ the masses. Recent installations on the main street of Yogyakarta use symbolism any Indonesian would immediately recognize: the bamboo runcing (spear) with bloodied tip reminds the elderly of their battle for independence from the Dutch. The bird cage carries the question: is your soul already dead? The military boot symbolizes oppression while it carries the slogan "I protect the people". Others are less obvious to ordinary Indonesians who tell me they appreciate the efforts but don’t understand.

Currently very active on the streets of Yogyakarta, two groups of artists in staunch competition with each other have revived the social realist poster with its glorified proletariat themes and slogans. They reject the elitism of galleries by using the streets as a direct route to the masses. Yet, in certain ways, these efforts at creating a wholly inclusive art are reproducing Suharto’s approaches. They too are pedantic and ideological, idealistic not realistic. What is worse, they are divisive; how can they construct ‘inclusivity’ in the streets, when they cannot amongst themselves? Yet, in this era of freedom, both have reached out for social realism, which is associated with the banned communist party, and thus remains the one discourse still illegal in the reformation era.

Since Suharto resigned on May 21 1998, the streets were freed for artists and activists to show their ‘inclusivity’ with the rakyat in their own domain. A flier reveals what these changes mean to the art community:

Now that the door of change is open, it is necessary for cultural movements to communicate to the public with the goal of developing awareness and changing morality. Art is the child of culture and our participation is required in the articulation of these movements. Compared with other arts, the medium of visual arts is significant because it can be appreciated directly and for the long term. Because of this, it is our intention that we can expand freedom, sensitivity, and responsibility, which can finally roll into a "new culture" which preserves a larger portion for morality and humanity (Aksi Seni Rupa Publik, information flier, 1998).

Thus, artists expressed their ‘inclusivity’ with the rakyat through location; that is, they were urged to mix with the people right on the streets. Inclusivity is further expressed through shared victimization. Artists, intellectuals, and rakyat alike demand a new moral and humane culture, with more freedom, sensitivity, and responsibility, than that which created the crises. The artists also specifically ‘speak to’ the people by teaching them how to take full advantage of the newly gained openness, where it should go, and how to get there – are these instances of ‘inclusivity’ or ‘speaking for’?

With so much concern for the rakyat in Indonesian art circles, I’d like to take a moment to seriously ponder what this means. To spur investigation, here are some quotes from reviews of exhibitions:

It is about time artists developed a more realistic connection with society by giving voice to a more critical style and vision. In this modern day, visual arts are no longer an expression of a social reality. Artists are still enjoying the ‘ecstasy’ of self-satisfaction (Surabaya Post, 16 December 1996).

The ensuing debate listed the themes modern artists were dealing with, although insufficiently. These are: politics, economics, social relations, and culture which are realized through life’s main influences such as religion, economic inequality, the State and its institutions, ideology, militarism, the supremacy of technology or through more individual structures such as the dominance of masculinity over femininity, affiliation, ethnicity/race, mythology and culture (ibid).

This explanation of ‘life’s influences’ is remarkably revealing in terms of identifying how deeply art is supposed to be embedded in politics and in precisely what direction and where artists or socially aware intellectuals need to be focussing their attention at this time in history. Those who take part in the critical discussion of the visual arts blame censorship and Suharto’s sociopolitical control mechanisms as the root of the problem. As critics’ discussions reveal, artists are expected to focus on the more pressing needs of society rather than an introspective, individualized gaze. Critics are literally demanding a more direct involvement between artists and the sad realities of the streets, despite the legal implications.

What about these post-reformasi debates? For the last several months, local experts have held seminar after seminar to discuss this role of art in politics and politics in art, now that the reformasi has arrived and the fears and restrictions on political content are gone. Yet, Indonesian art, according to many critics and artists themselves, seems to have lost its direction precisely because of the lack of a clear political statement. It would seem from the news reports that a great deal indeed is expected from artists:

Artists are still traumatized by the previous regime and its political taboos. Yet the merging of art and political themes is broadly considered the only road to a truly inclusive and fair Indonesian identity (KR, 18 Mei 1999).

Are Indonesians aware of the way they have been exploited for years for political purposes, asks Drs. Tulus Warsito. Political domination of the art world was achieved through enforced regulations which were extremely harmful to the artist and the art. From black-listings to the intensely complicated system of authorization required for exhibition, artists are struggling now to free themselves from the restraints that severely hampered the freedom to create (KR, 5 Mei 1999).

Finally, the intellectual distance between artists, their own work, and the rakyat is also brought into focus in a statement that not only scorns artistic ability and purpose, but the ignorance of society as well:

Even if artists were able to clarify their own visions, there still exists a controversy in a society that has no understanding of the meanings and symbols used in contemporary art (KR, 22 April 1999).

In a society protected by what Dwi Marianto calls "state criminalism – the defensiveness and paranoia of the political elite and the way they attempt to close off critical discourse" (Dwi Marianto, 1999:33), it should not be surprising that Indonesian artists are obsessed with people politics. Politics meant speaking out against injustice and was based on a deep and meaningful contact with the little people, a romanticized link to ‘the truth, or soul, of society’. Yet it may be important here to clarify the meaning of the word politics without forgetting the imposing context of surveillance, control, authorization, and censorship all designed to maintain the appearance of a normalized order. This order is based on enforcing the highly stratified nature of society, which is by no means recognized as part of the problem. Thus, ‘politics’ is anything that highlights the positioning of the rakyat in the social hierarchy and contests the way people in power go too far in abusing their rights over those who are lower in the social order. Yet, few contest the paternalism or the necessity of caring for, speaking for, or maintaining order among the rakyat. Despite a supposed intimacy with the rakyat (as made clearly obvious through populist imagery and symbolism), many artists and activists still believe that the rakyat are indeed ignorant and spontaneous, and thus, in need of protection.

All of this places Indonesian artists in an impossible dilemma. ‘Real art’ must criticize the blatant inequality of government policy as it defends the dispossessed rakyat by speaking for them. It must advocate for the rakyat by respecting their world and teaching others to respect it. It most certainly may not exclude them, either in vision or location. Artists must strive to break down the social, economic, and political boundaries that separate people by presenting art works that are clearly understood by all, and by exhibiting them in locations that are not exclusive. Is this the key to a ‘truly inclusive and fair Indonesian identity’? Since the reformasi, social and political themes in art are flourishing. Yet, does any of it reach the goals argued by critics and artists? Are such goals even attainable?

Within hours of Suharto’s resignation, an exhibition with the English language title "50 Years of Human Rights: Messages from Distortion" was organized and finally held on 18 November 1998 in Yogyakarta. Pamphlets with translations of the international convention on human rights were distributed to all who came. The images, installations and performances shocked Indonesian audiences who are not accustomed to public nudity, explicit images of torture, murder, or reminders of their own fears. The comments I heard from the audience were "saru!" (obscene) and "waton aneh" (flagrantly, even unnecessarily, shocking), hence, the performances and exhibitions were not really considered art. In a society well trained to keep its eyes shut, people do not want to see artworks which represent the violence that threatens a middle class lifestyle, which promote a glorified peasant lifestyle that is foreign to them, or which attempt to impose a kind of middle-class guilt. Indonesians "mistrust the idea of becoming successful or well known by trading on society’s problems" (Effendy, 1999:31).

Despite public distrust, the reformasi bandwagon is now overloaded with artists making statements about politics and violence through repetitive visual idioms. These idioms, often symbols of the 1945-9 battle for independence, images from any of the various massacres, social, political, economic or environmental disasters, or the silent stress these all cause, show the link between the conceptualization of national and local problems through objects which are now taking on the characteristics of pop art or localized kitsch. Artists attest to their social concerns through appropriating the objects of the streets in what Bourdieu called strategies of condescension. Repetition has drained these images of their impact. Described as consumption without essence, Moelyono (pers. comm., 1999) argues that these repetitive symbols are evidence of an extremely narrow understanding of the words most often used: freedom and equality. There is, he claims, an abusive visual hegemony among artists which has weakened the power of words and images. As a result, the previously ‘marginal’ have now become the mainstream. Thus, there is an inherent irony and even a dead-end frustration in this search for an inclusivity or a ‘fair’ national identity in visual art. Artists consume and reproduce experiences which they may or may not have understood, and which they long for and reject simultaneously (i.e., first-hand experiences of poverty, violence, etc.). Once an art form becomes accepted by the mainstream system it attempts to reject, it is no longer radical. With local and particularly international galleries and collectors now looking specifically for reformasi art, the critical focus artworks direct at the contemporary Indonesian environment is proof of their falling into the commodification trap (Suryatmoko, 1999). The problem is far deeper than whether or not an artist has ‘sold out’. As a great Javanese humanitarian (Romo Mangun) had said, "Indonesia is certainly weak in its love of truth, rationality, and fairness" (Bernas, 5 January, 1998).

Through this essay, I have tried to show that the streets of Indonesia are very consciously used as a space for negotiating meaning and as a source for its legitimacy in understanding local theories of identity. Power elites and artists vie for a voice with a people that both are highly dependent upon for their own legitimacy. Yet both further see the rakyat as needing their guidance. Like the so-called reformasi elites who sustain Suharto’s fear of the people and their potential for savagery, artists too claim a unity that looks all too much like paternal inequality. Thus, the rakyat, their streets, and artists’ representations of them, present vibrant insights into the directions and constructions of identity and meaning in Indonesia’s so-called reformation.

Laine Berman

Centre for Cross Cultural Research, ANU, 1999

Bibliography

Dwi Marianto. 1999. "Bored with polite language", Artlink Vol.19(3)p.33-5.

Effendy, Rifky & Damon Moon. 1999. "Fashion for civil disturbance", Artlink Vol.19(3)p.30-2.

Fischer, Joseph. 1994. The folk art of Java. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Lindsey, Timothy. 1993. In, Hooker, V (ed.) Culture and society in new order Indonesia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Pemberton, John. 1994. On the subject of "Java". Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Suryatmoko, Joned. 1999. "Verbalisme carut-marut dan komodifikasi seni". Bulaksumur. No.29/VIII:p. 20.

Budi Susanto, 1993. Peristiwa Yogya 1992 : siasat politik massa rakyat kota. Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

Wright, Astri. 1994. Soul, spirit, and mountain : preoccupations of contemporary Indonesian painters. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.