Elisa Martinez

March 26, 2002

Advanced Composition/ Personal Profile

Dr. Niiler

Betsy's Clothes

It was the week Jackie O died. I remember because Betsy and I took a taxi from the West Side to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and we saw the building, surrounded by cameramen and news trucks and reporters. We wondered why they were there. Betsy felt tired and decided she'd go home in the same cab, so I wandered around the museum by myself. I wanted to give her plenty of time to rest and I stayed longer than I really would have liked.

The Metropolitan Museum isn't as interesting alone. I looked at everything in the gift store twice and bought myself some posters with traveler's checks. When you don't have time to see much, the gift store is almost as interesting as the museum itself, and for some reason I had tired of Tiffany windows and Eighteenth Century Oil on Canvas. I don't remember how I got back to Betsy and Lance's apartment. I suppose I caught a cab, although it's just as likely I took the bus or the subway or walked. But Betsy would have wanted me to get a cab, so I think I took a cab.

The Metropolitan Museum isn't as interesting alone. I looked at everything in the gift store twice and bought myself some posters with traveler's checks. When you don't have time to see much, the gift store is almost as interesting as the museum itself, and for some reason I had tired of Tiffany windows and Eighteenth Century Oil on Canvas. I don't remember how I got back to Betsy and Lance's apartment. I suppose I caught a cab, although it's just as likely I took the bus or the subway or walked. But Betsy would have wanted me to get a cab, so I think I took a cab.

When I got back to Betsy's, we heard on the news that Jackie was sick; her cancer had become much worse. That's why the reporters were there. They hoped to film the doctor going in or out, or perhaps catch a glimpse of Caroline or JFK, Jr. I thought it was crass, as if they were waiting for her to die, and told Betsy so. She thought so, too, but mostly she seemed sad that Jackie was sick, as if they had been friends together in a distant past. "I remember just thinking that Jacqueline Kennedy was so elegant. I saw a documentary she did about redecorating the White House. She was just such an extraordinary woman, Elisa, so poised and graceful. And such a wonderful hostess."

* * * * * *

That had been my own opinion of Betsy: extraordinary, poised, graceful. When my family first moved to New York City, she took us to Fairway, the famous Upper West Side grocery store. Betsy wheeled her son Chris' stroller through the thick crowd of shoppers with amazing dexterity. She wore old tennis shoes that day, but I learned later that whenever she walked somewhere dressed up, she would wear the same old tennis shoes and carry her dress shoes in a plastic bag. A couple of blocks before arriving wherever she was going, she'd stoop down and switch shoes. The dress shoes always matched, of course.

Betsy's blonde hair was thin, and she wore it pulled smoothly back to the nape of her neck, so that when you looked at her face, you mostly saw her eyes and her smile. Betsy was tall and willowy. Not surprisingly, she looked even taller, almost sylph-like, when she wore heels. Betsy kept her shoes in a shoe bag on the back of the bedroom door. I remember one pair, a smart little executive style in navy and white. Her shoes would have made Audrey Hepburn jealous. At least 20 pairs hung behind Betsy's door, nearly all of them heels.

Betsy bought us cinnamon raisin bagels that morning at Fairway, confessing her enjoyment of them as if it were a vice. As we left the store, she zigzagged across the NYC sidewalks, pushing Chris, passing him little bits of bagel, and weaving a fascinating tapestry of conversation. She combined reminiscence with advice and sparkly tidbits.

"Everyone goes to Fairway because their vegetables are so wonderful, but you should really go to Zabar's, too. They sell chocolate like this in chunks by the pound," pulling a block of chocolate out of her bag. "I'll take you there sometime."

"That's the building where Yoko Ono lives," pointing to a hideously gray structure guarded by black cast-metal gargoyles mounted on poles. "We'll eat in Strawberry Fields. They named it after the song, you know." I didn't, but I pretended.

We arrived at the park a few minutes later for our picnic. Betsy spread out a sheet, spider webbed with huge lavendar tie-dye patterns. We sat down on the wild designs and she began to explain, "We call these my 'un-faith clothes.' When I was expecting my first child, we didn't have money for maternity clothes. We prayed and still didn't have any money, so I finally decided to tie dye the sheets and make myself some clothes. Tie dyeing was very 'in' then." An explanatory remark.

Of course. I couldn't imagine Betsy wearing anything that wasn't "in."

She continued gently, "I miscarried later, and never made the sheets into clothes. By the time I was pregnant with Samuel, we had the money to buy my clothes. We kept the sheets... they remind us that God knows what we need better than we do." Betsy's miscarriage had been difficult to accept, but perhaps not so surprising. Her mother and sisters had all miscarried at least once. She told me it was because they'd grown up in Riverside, CA, where everyone breathes chemicals from the orange groves.

Betsy once showed me how to set out the coffee and cookies for refreshments after church. She said she wanted me to know how to do it in case she wasn't there. Betsy had purchased tablecloths and thick plastic to cover them. She brought her own silver plated coffee service, a wedding gift, to use each Sunday evening. Betsy told me, "Silver plate is nice, but when you get married, you should really ask for pewter. It always looks wonderful and never wears out." She showed me how she always arranged the plastic spoons, staggering them up and down and alternating pink with burgundy. The spoons matched the tablecloth, of course.

* * * * * *

Six years later, during the week that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis died, I went back to New York to stay with Betsy and Lance and the boys for a while. Betsy was sick, and needed someone to fix the boys' lunches and pick them up from school. She was on a special diet, so I went to Fairway and bought apples and carrots for her several times a week. Every morning I fed carrots into the juice machine by the pound, discarding the sweet bright orange pulp, pouring the juice into a glass. Every morning she drank it, washing down handfuls of pills. She bought a mango at Fairway one day when we'd gone together and we ate it that same morning, sitting at the kitchen table talking seriously about something I can't remember. I know it was serious, but all I remember is the mango and how much she enjoyed it. Betsy called Chris in to let him suck the seed even though it was messy.

Betsy also needed help with some projects she didn't have the energy to complete. I stamped and addressed 300 Christmas cards, even though it was only May. I put all of her sons' children's books in order. Betsy's books outnumbered her Christmas cards, and she organized them with a complicated color system, using little stickers on the spines of the books.

"The Bible stories are red, and the books about machines are blue. The classics and fairy tales are green, and the books about animals are dark green..."

I wondered if the system would last long with a ten-year-old and an eight year-old in the house, but Betsy was sure it would work. Someone had told her when she was an Esteé Lauder executive that a fisherman's tackle box made a wonderful storage case for makeup, so Betsy used one. And when she had sons, she kept their Legos in the same sort of tackle box, arranging the blocks in little spaces by shape and color.

Besty and I went shopping during this time. Her illness made going out a chore, but she window shopped with me one day on Columbus Avenue, the 5th Avenue of the Upper West Side. We visited all my favorite stores: Putumayo, Express, and the Gap. At the Gap, Betsy found an adorable straw hat with a scarf and a matching skirt. The skirt was made of some sort of filmy navy fabric with white vines and flowers trailing over it. The hat really clinched the outfit, though. Betsy put the hat on, looked in the mirror, and made me try it on, too.

"It isn't quite your style, is it?" she asked. I'm not sure why, but I think she was relieved that the hat which looked good on her, didn't look as good on me. "I really can't afford to get these now, but aren't they wonderful? And you have to buy the scarf with the hat; it doesn't look right without it. Of course, then you have to buy the skirt, too, so you have something to wear it with." She finished, laughing, and we left the store. Whenever Betsy laughed, her face glowed with a shy pale light nearly eclipsed by her brilliant smile.

Betsy told Lance about the hat and scarf and skirt that night. "I was going to buy them, but..." Her voice trailed off leaving an empty space.

"Well, why didn't you?" asked Lance.

"I'm not going to be here much longer, and I thought it seemed like a lot to spend," replied Betsy, almost apologetically.

Lance turned to look at her, a strange sharpness in his eyes. He spoke with a tone of voice I had never heard before and have never heard since, as if the sound were coming from far away, deep down in some constricted hole.

"I want you to go back to the store and buy them." I sensed Lance's urgency. Betsy must have too, because she went back the next day to buy the hat, scarf and skirt. She brought them home and tried on the hat for Lance.

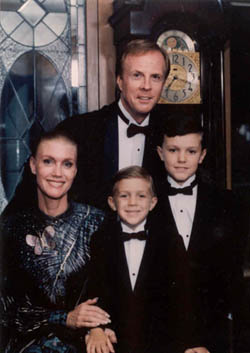

"It makes you look ten years younger." Lance smiled, the artist in him coolly appraising Betsy's chic flair and the hat which set it off, the husband admiring his wife's serene beauty. Lance appreciated serenity. They ate by candlelight every night because, according to him, "it makes the boys calm down for dinner."

Betsy was pleased, too. I put the hat on, and they agreed, "It doesn't look the same on you."

"Actually," Lance decided finally, "the problem is, it makes you look ten years younger, too."

I was eighteen. But Betsy was in her forties and the hat really did look good on her.