What is Blanziflor et Helena?

What is Blanziflor et Helena? This question occurred to me during a rehearsal one evening of the Dallas Symphony Chorus. We had gotten to the point of really wrapping ourselves around the music and were going full tilt through the piece de capo al fin. At this particular point in the score, utmost choral energy is brought to bear on this anthem before the music returns to the quieter opening statement. Although this occasion was not my first encounter with Orff's Carmina Burana, this seemed the opportune time to satisfy my curiosity about the work - to become immersed in the verse, so to speak. Being enough of a Medieval historian and linguist, I was further intrigued by the verse, its origins and language. So here is an interpolation of what I already knew and what I found out.

After 1000 A.D., the flame that the Church had kept alive through so many years of harsh struggle burst into a fire of learning. Man didn't simply emerge cautiously from the season of destruction and decay following the collapse of the Roman Empire. He leapt. There occurred an expansion of the human spirit that has occurred only two or three times in recorded history. It was an age of intense intellectual activity, of creative energy and artistic genius, of great passion, spiritual and corporeal. This was the month of April in the year of Western European Civilization.

Certainly over all was the Church. For centuries, it had been the repository for civilization. Now it came into the full realization of its powers, bringing to society organization out of chaos and human charity out of cruel barbarity.

It is difficult in our age to relate to the idea of the Church held by Medieval man. It was his mother and father: it cared for his soul and looked after his physical needs. It provided him with inspired visions of heaven by means of its vaulting and colorful cathedrals.

Not only that, the Church was a relatively democratic institution. Any man from any walk of life had the opportunity to rise to the top by intelligence, skill, ability and hard work. Having money and a powerful family didn't hurt either. Therefore nearly all men of intellect or with connections joined its ranks. As its language was Latin, it was international in scope and appeal. It owed allegiance to no nation and no one was hampered by his native tongue. Everyman would not have comprehended our idea of nationhood: He did not belong to a nation, he belonged to the Church.

Of course, not everyone who set their sights on an

ecclesiastical career in the Church had either the staying power or the connections

necessary to realize any high ambitions. However, although the remuneration was barely of

subsistence level, even the lower ranks of clergy enjoyed privileges not given to those

outside the vows of holy orders: There was freedom from secular taxes, exemption from

military service, freedom from trial in a secular court -- for any reason, and freedom from

the death penalty. On the other hand, anyone who struck a cleric was himself subject to

the death penalty. So, as Peter Cook might put it: "I'd rather be a cleric than a

peasant."

Top

What, you say, does all this have to do with Carmina Burana?

There existed a sub-society of errant intellectuals, literate and foot-loose, relying on hand-outs, tutoring and odd jobs for their living. Some were students, who had not yet or only recently completed their education, traveling from university to university or from university to home and back again. There were clerics who, without influence or money to obtain an office or preferment and lacking importance, were left free to wander. Others, too difficult to live with in a communal environment, were ousted from their monasteries by their brothers. In this soup were the reprobate or runaway clerics who used the tonsure as a protection and abandoned themselves to wandering. (There was a Medieval penchant for travel -- no easy undertaking -- which expressed itself also in pilgrimages, Crusades and trade routes.)

It was always easier to get a handout at an estate, abbey or inn if you could be entertaining. As you drank your host's wine, you made up songs and music relying on your classical knowledge and profane wit, for the longer you kept your host entertained the more times your cup could be emptied and filled again. And if your poetry and songs were particularly moving, funny or ribald you might even be awarded a cloak or vest before your departure.

In adversity, there exists camaraderie, so these wandering verse-makers, known generally as goliards, formed a pseudo-guild they could belong to (there was also a Medieval penchant for the masses to group together in anonymity). Manuscripts obviously existed of such songs belonging to individual members of this group of wandering poets, the quality of work varying from obvious student versing to genuine poetic efforts.

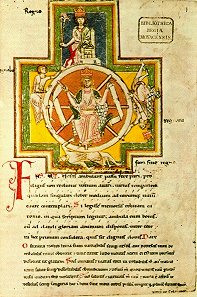

Some of these songs and poems were compiled into a manuscript around 1250. Scholars have identified about two or three hands who shared in the work, recording and illustrating selections that must have brought a moment's diversion to a few people. They were indeed meant to be sung; however, except for some diacritical markings over the text, the music for these verses has been lost. As monasteries were the normal keepers of various books, the manuscript known as Carmina Burana wound up in a monastery in northern Europe. Of course, it could not be kept with the sacred library; so it was put with the indexed books and secular manuscripts where it was found and brought back to life in the early 1800s.

Who was the audience for these poems?

|

|

There was the ecclesiastical lord. The average person who

had realized some of his ambitions looked upon the Church as a career rather than a

calling. And, although he embarked on a career of high spiritual attainment, he wasn't a

killjoy. (It is illuminating to consider that the three most widely read books in Western

Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries were The Romance of the Rose, The

Golden Legend, and Reynard the Fox. Comic images frequently appeared as well

in the illuminated pages of holy manuscripts.) He may have been pious but he was not dead.

In fact, celibacy was more or less haphazardly practiced, generally being encouraged but

not strictly enforced by the Church. So there were priests and clerics who could openly

appreciate a woman's charms and many who were indeed married. He could entertain guests,

enjoy a joke, take part in a roundelay, and appreciate aves to desirable women. In fact,

the ecclesiastical lord was in most part expected to take in travelers, see to their

needs, and provide them something to eat and drink. And if they paid him in turn by

singing a ditty or two, well, how merry an evening that might be.

There were secular lords who were also grateful for an evening's entertainment. And of course there were fellow travelers who might encounter each other at a way station, exchange poems, stories and music, drink together, dice together and perhaps persuade the innkeeper to save his soul by a little charity. |

What was of interest to this audience?

There are spring songs, pastorals and songs of youth, love and women (for example, in CB, #4 and #5). Who could concentrate on serious matters when the earth was coming back to life in the Spring? What hearty scholar could remain by his pot of ink upon hearing or forget a young maid's plea, "Quid tu facis, domine? Veni mecum ludere?" (What are you doing master? Come and play with me.) The love described in these poems doesn't always lead to fulfillment. There are tender lyrics of unrequited love (#7, #16) and some lamenting the faithlessness of women. Some are true love lyrics that drew upon classical poets and mythology as well as contemporary stories of love for their inspiration. There are no considerations of morality or responsibility. The women are not idealized visions and for the most part (except for the German student's naive lyrical dream of romancing Eleanor of Aquitaine CB #10) are of humble origins, flesh and blood, not too young nor too old; not promiscuous but then not too virtuous either. A note written at the back of a vocabulary book sums up the spirit of these poems: "And I wish that all times were April and May, and every month renew all fruits again. And every day fleurs de lis and gillyflower and violets and roses wherever one goes, and woods in leaf and they to love each other with a sure heart and true, and to everyone his pleasure and a gay heart."

Of course, other matters sometimes occupied the minds of these poets. There are drinking songs (CB #14), confessions of what it's really like to be on the open road and susceptible to the fortunes of fate (CB #1, #11). Humorous songs were always well received. Although the conceit is not to modem tastes, the "swan song" (CB #12) must have been pretty funny. And parody. A lyric that poked fun at a mutual acquaintance through parody would always find a ready audience. These were leveled not at the Church, but at the abuses of some of its members. The parody/drinking song of the Abbot of "Sugarcake" (CB #13) who succumbs to dice and gives fair warning to his opponents surely must have drawn a knowing nod from a sympathetic and good natured prelate, who may have known the object of the satire. There were parodies of hymns and sacred rites which the authors knew so well and take-offs on religious subjects such as "The Gospel of the Silver Mark," "The Mass of the Topers," and "A Prayer Book for Roisterers."

The Church Finally Cracks Down

The type of verse characterized by the Carmina belongs to an ephemeral moment in time. They reflect the earthiness of a particular class closely allied to university and church although not really a part of either. They are spontaneous expressions of unreflective and wanton youth and without the stuff of great literature. They mirror an age but do not transcend its origins. The Church, ever vigilant over instincts out of control, was really quite patient for over 200 years with these outpourings. Besides, it's one thing to acknowledge among colleagues the shortcomings of one's own; it's quite another to have the barbs of truth clothed in ribald lyrics and bubbling all over Paris.

Although edicts, largely ignored, were issued from time to time, an edict with teeth was issued in 1281 by the Council of Salzburg. It described the adherents of this verse as going "about in public naked; they lie in bake ovens, frequent taverns, games, harlots; earning their bread by their vices and cling with obstinacy to their sect." The Council decreed that any cleric (read also student) who composed or sung licentious or impious songs would lose his clerical rank and privileges. However, this decree may have been like a strong gust of wind on a house of cards, since by 1250 the age of the wandering verse was over. The effect of the 1281 edict was that those who clung to their way of life and verse making sank to the level of jongleurs. The lyrics fell out of literature and into doggerel. The final blow came at the end of the 13th century when Dante chose Italian for his literary undertaking. Vernacular became art and drama and Latin retreated to the monastery.

By the Way

Oh, by the way, about Blanziflor et Helena. This love lyric

(CB #24)

addressed to a maiden starts with praise parodying a hymn to the Virgin and bestows upon

her the graces of famous mythical and classical epitomes of beauty and love --

"Blanziflor (Blanche Fleur) et Helena, Venus generosa." Woman at once becomes

the goddess of carnal pleasure and the mother of God, but that's another

story.