The Rus' were ruled by a family of princes who claimed descent from Viking raiders. These princes moved up a chain of hierarchy, ruling progressively more important cities until reaching Novgorod, later Kiev, and finally Vladimir in the 13th century. Succession was theoretically mandated by a system of inheritance, but just as often occurred through inter-city warfare.(1)

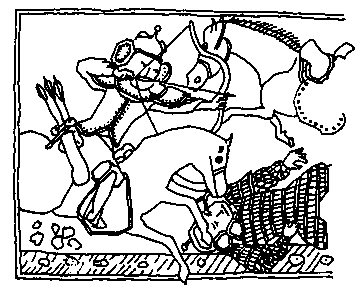

The princely household, or druzhina, included a bailiff, a master of horses, a steward, and an adjutant.(2) The druzhina provided the trained cavalry for the city. Princes drew income from taxes, tribute, court fees, and judicial fines. Most princes were wealthy and contributed to the well being of their towns through building churches, performing acts of charity, and sponsoring sumptuous feasts.

In Novgorod, a popular assembly called the veche could exercise veto power over the prince. This assembly required the prince to live outside the city. It occasionally deposed a prince and invited another to rule. Summoned by peals of the city bell, the populace came together in front of the prince's palace or St. Sophia's. Issues were decided by direct voting-the process sometimes turning into a brawl. The veche elected a town officer from among the landowners. There is debate about who comprised the veche-archaeological reconstruction of the town square indicates that there was room for only 300 people.(3) Some sources argue that the veche was an assembly only for landowners, but it may have been a representative assembly.

The town officer exercised governmental powers, operating a town hall and using an official seal, while maintaining an uneasy relationship with the prince. Some historians postulate that a similar division of power was mirrored in other Russian cities: the authority of the prince and his druzhina limited by the landowners and town assemblies.(4) Some degree of restraint was normally exercised on the prince by custom and popular opinion.(5)

Laws of the Kievan Rus' are preserved in several manuscripts called Pravda. In these documents, the penalty for murder was a heavy fine, similar to the wergild, determined by the class of the murder victim. Significantly, the death penalty was rare and imprisonment absent in Russian law.(6) Corporal punishment and torture are mentioned only once each, and then only for slaves and peasants. Trial by ordeal is mentioned briefly, in contrast to Western Europe, where torture and trial by ordeal were often part of the judicial process. Much of the written judicial code concern fines for wrongs, some very specific-cutting off a finger three grivna, cutting off a beard twelve grivna...(7) Other sections cover compensation for property damage, theft, and assault and rules of acceptable evidence. Laws protected shipwrecked merchants from their debtors. Slavery was limited by regulations in the Pravda, which on the other hand also provided for return of runaways.

Church law applied to all citizens on certain topics. The Church had its own courts, the hierarchy could level fines, impose fasts and prayers as penance, and deny communion. Religious statutes regulated marriage, limited divorce, and outlawed incest and sexual intercourse outside marriage. The statutes also protected people from slander and mandated respect for parents. These religious laws overlapped to some degree with secular laws.(8)

It is difficult to decipher the units of money mentioned in the historic record. Sources vary as to the value and meaning of the terms grivna, bela, kuna, and nogata, although a grivna has been equated with a ounce of silver. Cattle, marten skins, silver bars, and various foreign coins were all used as currency. Kievan Rus' only briefly issued its own coins.

The period of rule by the Golden Horde saw the super- imposition of Mongol rulers over the Russian Princes, who were kept in place to exert the Mongol's will. These princes were forced to conduct censuses, impose taxes and levies, and control the populace. Continuous tension resulted, punctuated by occasional rebellions. Power was concentrated in the princes, while the democratic institutions of the Kievan Rus' were gradually suppressed. This occurred less in Novgorod, where the steppe warriors were effectively kept at arms' length. The Mongol period also influenced Russian law, introducing the death penalty for many offenses and other harsh measures.(9)

(1)See Cross, throughout.

(2)Dmytryshyn, pp. 44-50.

(3)Society for Medieval Archaeology, p. 94.

(4)Vernadsky, Kievan Russia, p. 186.

(5)Ibid, p. 288.

(6)Ibid, p. 293, Kaiser and Marker, pp. 27-29.

(7)Dmytryshyn, p. 46-47.

(8)Ibid., pp. 50-54.

(9)Vernadsky, Russia and the Mongols, p. 107.