Before Christianity, the Rus' worshipped many gods, spirits and natural

forces. We know about the Pagan Gods from chronicles compiled by Christian

monks, archaeological finds, and persistent folk beliefs recorded centuries

later.

Before Christianity, the Rus' worshipped many gods, spirits and natural

forces. We know about the Pagan Gods from chronicles compiled by Christian

monks, archaeological finds, and persistent folk beliefs recorded centuries

later.

Before Christianity, the Rus' worshipped many gods, spirits and natural

forces. We know about the Pagan Gods from chronicles compiled by Christian

monks, archaeological finds, and persistent folk beliefs recorded centuries

later.

Before Christianity, the Rus' worshipped many gods, spirits and natural

forces. We know about the Pagan Gods from chronicles compiled by Christian

monks, archaeological finds, and persistent folk beliefs recorded centuries

later.

Beyond the Slavic Gods were a matrix of nature spirits and other elemental forces. Scholars are still sifting through folk tales, chronicles, artwork, rituals, and songs to decode the complex ancient Slavic world view.(1) This matrix was the ground onto which the Greek Orthodox church was grafted, and it is essential to understanding the Russian character.

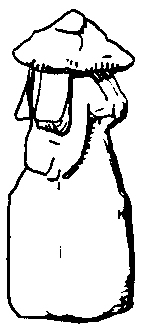

Ancient Russians found the natural world full of life; they venerated trees

and rivers and considered them inhabited by female entities. Indeed, trees

were decorated with offerings through the 19th century.(2) Ancestor

worship-revering deceased relatives as household gods-was another aspect of

their belief. A carved house spirit often stood near the stove.(3)

Offerings of bread, curds, and mead continued to be made to this house

spirit until at least the 12th century.(4) In later times, a corner of the

house was reserved for an icon, which may have represented an evolution of

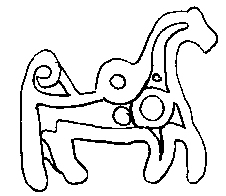

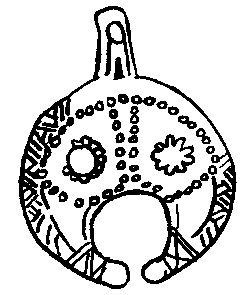

this practice. Amulets unearthed at Novgorod hint at powerful beliefs: moon

symbols, horses with jingles, a Medusa with an incantation, and a bone

inscribed with a dragon, and a circle with nine rays, probably representing

the sun.(5)

Ancient Russians found the natural world full of life; they venerated trees

and rivers and considered them inhabited by female entities. Indeed, trees

were decorated with offerings through the 19th century.(2) Ancestor

worship-revering deceased relatives as household gods-was another aspect of

their belief. A carved house spirit often stood near the stove.(3)

Offerings of bread, curds, and mead continued to be made to this house

spirit until at least the 12th century.(4) In later times, a corner of the

house was reserved for an icon, which may have represented an evolution of

this practice. Amulets unearthed at Novgorod hint at powerful beliefs: moon

symbols, horses with jingles, a Medusa with an incantation, and a bone

inscribed with a dragon, and a circle with nine rays, probably representing

the sun.(5)

Goddess worship, to the degree that it existed, was deeply hidden. The only female deity in the pagan Russian pantheon was Mokosh. She has been identified with "the mother goddess" embodying the mysteries of farming, motherhood, and the earth.(6) She emerges in veneration of the Madonna, Russian folk tales, and the phrase "Mother Russia."(7) Aspects of a paleolithic tripartite goddess may perhaps be seen in Russian folklore: the witch-crone Baba Yaga; the fertile and maternal spring, Golden Baba; and the various tales of maidens-seductive mermaids and forest and river spirits-Rusalka, Kupalia, and Koleda.(8)

Ancient beliefs included a calendar of rituals honoring agricultural and human life cycles. Winter celebrations included mummers, revelers in animal masks, ritual transvestitism, and noisy antics. Late winter featured festive sledding as a courtship and fertility ritual. With spring came dances and the decoration of birch trees. The summer solstice was greeted with bonfires, baths, and immolation of straw and flax effigies. Varied ceremonies cycled throughout the year: certain days to sing special songs, brew beer, initiate spinning, embroider, and so on. The festivals are documented, but imperfectly understood. They continued throughout the period, especially in rural areas, despite protests and attempts at suppression by the church. In short, in Russia as elswhere, conversion was a long, gradual process and many of Russia's neighbors, including the Finns, Lithuanians, Kumans, and Turks remained pagan for centuries thereafter.

(1)Brumfield.

(2)Vernadsky, Kievan Russia, p. 49.

(3)Society for Medieval Archaeology, p. 98.

(4)Vernadsky, Kievan Russia, p. 49.

(5)Thompson, p. 10.

(6)Cross, p. 38, footnote 55; and p. 93 footnote 80.

(7)Brumfield.

(8)Cross, p. 116 (980).

(9)Ibid, p. 93.

(10)Thompson, p. 3-4.

(11)Ibid, p. 10.

(12)Cross, p. 65 (904).

(13)Vernadsky, Kievan Russia, p. 50-52.

(14)For a more complete discussion see Chennault and Hubbs.

(15)Brumfield p. 62.