Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary, Hypercalcemic Type A Clinicopathological Analysis of 150 Cases

Robert H. Young, M.D., Esther Oliva, M.D., and Robert E. Scully, M.D.

From the Department of Pathology, Harvard Medical School and the James Homer Wright Pathology Laboratories or the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Robert H. Young at Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. MA 02114, U.S.A.

The clinical and pathological features of 150 cases of ovarian small cell carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type are described. The patients ranged from 9 to 43 (average 23.9) years of age. The serum calcium level was known to be elevated in 49 of the 79 patients (62%) whose preoperative calcium levels were measured. Four of these patients had symptoms of hypercalcemia, and one of them had undergone neck exploration with negative results before the ovarian tumor was discovered. At laparotomy the tumor was unilateral in 148 cases (99%). Extraovarian spread was present in approximately half the cases. The tumors ranged from 6 to 26 (average 15.3) cm in greatest dimension. Microscopic examination disclosed various patterns, the most common of which was diffuse sheets of cells punctured by variable numbers of follicle-like spaces; the tumor cells also grew in nests, cords, clusters, and singly. The follicle-like spaces, which were present in 80% of the cases, contained fluid that was almost always eosinophilic and rarely basophilic. Glands or cysts lined by mucinous epithelial cells were present in 12% of the neoplasms. The neoplastic cells were typically small and round with hyperchromatic nuclei and brisk mitotic activity. Fifty percent of the tumors, however, also had a variable component of cells with moderate to abundant amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, which sometimes contained large hyaline globules and large nuclei that were typically paler and had more prominent nucleoli than the small cells. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the epithelial nature of the tumors, as did electron microscopy, which characteristically showed abundant dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum. Five of seven tumors investigated by immunohistochemical staining for parathyroid hormone-related protein showed positive results. All 23 tumors examined by flow cytometry with interpretable results were diploid. Fourteen of 42 patients (33%) with stage IA disease for whom follow-up information is available remained well and free of disease 1-13(average 5.7) years postsurgery; 23 died of their disease, usually within 2 years; and five had recurrences but were alive at last follow-up. Almost all the patients with tumors of a stage higher than IA died of disease, but one patient with stage IIB disease who received intensive chemotherapy and radiation therapy is alive and apparently free of disease at 7 years. Features in stage IA tumors that appeared to be associated with a more favorable outcome included an age >30 years, a normal preoperative calcium determination, a tumor size < 10 cm, and an absence of large cells. The tumors in this series were frequently misinterpreted initially as a variety of other ovarian neoplasms, most commonly adult or juvenile granulosa cell tumors or a primitive germ cell tumor, but the characteristic microscopic features of the small cell carcinoma facilitate its distinction from those tumors and others with which it may be confused. Analysis of the various types of therapy in the present series suggests that a procedure that includes bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be optimal for patients with stage IA tumors. The role of adjuvant therapy is unclear. Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy for high-stage and recurrent tumors has been generally disappointing, but it has occasionally resulted in long-term survival and possible cure.

Key Words: Ovary--Small cell carcinoma--Hypercalcemia.

In 1982 the clinical and pathological features of 11 cases of a distinctive undifferentiated carcinoma of the ovary that was associated with hypercalcemia in all the cases were described (18). The tumor was designated "small cell carcinoma" because the small size of the tumor cells was in marked contrast to that of the cells in most undifferentiated carcinomas of the ovary. Fifty additional cases have been reported subsequently by others (1,9,10,17,26,31, 33,34,38,40,43,49,50,55,61,66,67), nine only in abstract form (26,33) and six with an emphasis on ultrastructural findings (43). In recent years our experience with a large number of these neoplasms has revealed several potentially confusing pathological features, including, frequently, a content of large cells with abundant cytoplasm. Also, although the tumor is associated generally with a poor prognosis, the results of therapy in some cases provide a glimmer of hope for the future. This article reports the clinicopathological features of our first 150 cases.

Although the term small cell carcinoma was chosen to designate this ovarian neoplasm, it differs markedly clinically and pathologically from the small cell carcinoma that is most common in the lung and other organs. In retrospect, the designation small cell carcinoma is not an entirely satisfactory designation for a tumor that often contains large cells, which even occasionally predominate. Nevertheless, this term describes the most characteristic and generally predominant morphologic feature of the tumor. To avoid confusion with the much more common and better known small cell carcinoma of neuroendocrine type, which is rarely primary in the ovary (22), we refer to the ovarian tumor under discussion as small cell carcinoma, hypercalcemic type and the former as small cell carcinoma, pulmonary type. We designate the occasional small cell carcinomas of the hypercalcemic type with a predominance of large cells as the large cell variant of the small cell carcinoma, hypercalcemic type.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All 150 cases, including the 11 cases from the initial report, were obtained from our consultation files (143 from R.E.S., seven from R.H.Y.); they include 15 cases that have been reported by others ( 1,9,26,34,38,40,49,52,61,67). Clinical, operative, and gross pathological data were obtained from the referring pathologists or the patients' physicians. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were examined in all the cases, and mucicarmine, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), Masson trichrome, Grimelius, and reticulum stains were also examined in some of the cases. The results of the last four special stains are given in our first article on this tumor (18), and since they do not play a role in its evaluation they are not repeated here. In 36 cases the tumors were also studied immunohistochemically, with the results of the first 15 described elsewhere (4). Flow cytometry was performed in 25 cases and electron microscopy in 19 cases, and because these results have been reported elsewhere (19,21) they will not be repeated here but will be referred to in the Discussion. Statistical analysis was performed with the use of the Fisher exact test. Freedom from recurrence was correlated with stage, age, serum calcium level, tumor size, presence or absence of a large cell component, type of initial operation, and type of adjuvant therapy. The presence or absence of a large cell component was correlated with the presence or absence of hypercalcemia.

Clinical Presentation, Findings at Laparotomy, and Initial Therapy

The patients ranged from 9 to 43 (average 23.9) years of age. The number of patients in each decade is given in Table 1. Two patients were a mother and daughter, and two were first cousins. In another case the patient's mother was reported to have died of ovarian "carcinoma" at 31 years of age, but we have been unable to review the slides of the mother's tumor. The clinical presentation is known in 124 cases. As the initial symptom 50 patients had abdominal swelling, 43 had subacute abdominal pain, two had acute abdominal pain, and eight had both abdominal swelling and pain. Four of these patients also complained of vomiting, and one had ascites with bilateral pleural effusions. Four patients had fatigue, lethargy, polydypsia, and polyuria, symptoms considered to be related to associated hypercalcemia. One of these patients had had a neck exploration for presumed parathyroid disease, with negative results, before the ovarian tumor was discovered. Two patients had fever and were found to have adnexal masses on pelvic examination. One patient complained of urinary frequency, one had rectal pressure, one had amenorrhea for 4 months followed by signs and symptoms of an acute abdominal disorder, and two had irregular menses. The tumor was found on routine pelvic examination in seven patients, three of whom were pregnant (one case) or had recently been pregnant (two cases). Two tumors were discovered at the time of cesarean section, and one was palpated during a hernia repair. One patient had manifestations related to metastases in the brain, liver, and lungs.

TABLE 1.

Number of patients per decade

(present series)

The preoperative serum calcium level, known in 79 cases, was elevated in 49 cases, including the four with clinical manifestations attributable to hypercalcemia, and was normal in 30. The exact calcium level was available in 27 of the cases with elevated levels and ranged from 11.6 to 17.6, with a median of 15 mg/dl.

At laparotomy the tumor was found to be unilateral in 148 (99%) of the cases. In five of the cases designated as unilateral the contralateral ovary was involved as part of extensive abdominal spread and therefore was not interpreted as the site of an independent primary tumor. The laterality of the ovarian tumor, known in 134 of the unilateral cases, was right in 74 cases and left in 60 cases. Seventy-five tumors (50%) appeared to be stage I (50 were stage IA [33%], one was stage IB, 24 [16%] were stage IC, eight [5%] were stage II, 65 [43%] were stage III, and two [1%] were stage IV). Careful staging was done, however, in only a minority of the cases, and therefore many of the tumors were probably understaged. The nature of the initial operation, known for 125 cases, was unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in 69 cases, total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in 45 cases, hysterectomy with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in five cases, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in four cases, and ovarian cystectomy in two cases. Because of the common presence of tumor spread, additional procedures (such as omentectomy, debulking of extra-ovarian tumor, lymph node dissection or sampling, and biopsies of peritoneal tumor) were performed in many cases. Most of the patients received chemotherapy post-surgery, and some also received radiation therapy alone or combined with chemotherapy. The anti-neoplastic agents administered most often were varying combinations of vincristine, vinblastine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and etoposide.

RESULTS

Follow-up

Follow-up information on patients who died, had a recurrent tumor, or survived without disease for > 1 year is available for 42 of the 50 patients with stage IA tumors. Fourteen of them (33%) were alive without evidence of recurrence 1-13 (average 5.7) years postsurgery. One additional patient had a reelevation of the serum calcium level 6 months after surgery and underwent hysterectomy with left salpingo-oophorectomy; no tumor was found at operation or in the resected specimen. While she was receiving a chemotherapy regimen used for small cell carcinoma of the lung, the calcium level returned to normal. One year later a second-look laparotomy gave negative results, and she was well at last follow-up 4 years after her initial presentation. Another patient treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy for recurrent tumor was alive at 45 months (Table 2, case I). Still another patient, who was found to have paraaortic lymph node metastases 5 months after surgery, was well 4 years later after receiving chemotherapy (Table 2, case 2). Two other patients were alive with recurrent tumor at the time of last follow-up 6 months and 32 months after surgery. Twenty-three patients are known to have died of their disease: 13 within 1 year, three between I and 2 years, six between 2 and 4 years, and one at 7 years and 9 months (Table 2, case 3). Most of the patients who died but survived > 1 year had recurrent tumor in the first year after presentation. The one patient with stage IB disease died of tumor 2 years and 6 months postsurgery.

Follow-up until death or for >6 months is available for 20 of the 24 patients with stage IC tumors. Eighteen died of their disease, 14 within 1 year and four I-2 years postsurgery. Two patients were alive with disease at 19 and 52 months. Follow-up is available for all eight patients with stage II disease, seven of whom died of tumor, four within a year and three between 1 and 2 years. One patient was alive and well at 7 years. Details of that patient's treatment have been reported elsewhere (9) and are summarized in Table 2 (case 4).

Follow-up until recurrence or for >3 months is available for 52 patients with stage III disease. Thirty-two of them died within a year, 12 between 1 and 2 years, and two between 30 and 72 months after operation. The last patient, who received 5,360 rad to the abdomen and pelvis postsurgery was well for 5 years, when the tumor recurred (Table 2. case 5). Recurrence developed in two additional patients 4 and 13 months postsurgery, but they were subsequently lost to follow-up. Another patient was alive with persistent tumor at 2 years (Table 2, case 6). Three patients were alive and well at 7, 9, and 30 months (Table 2, case 7) after operation. One of two patients with stage IV disease died at 11 months, and the other had extensive disease at last follow-up 6 months postsurgery.

In all the cases in which both the preoperative and the postoperative serum calcium levels are known, the level returned to normal after removal of the tumor. In many cases it rose again in association with recurrence of the tumor. Recurrent tumor typically involved the pelvis and abdomen in a manner characteristic of ovarian cancer in general. Parenchymal liver metastases were present in a number of cases, as was involvement of abdominal and pelvic lymph nodes. In some cases distant spread to lungs, brain, and bones was documented.

TABLE 2.

Cases with favorable response to therapy

# | Stage | Postop | after first operation |

|||||

(SCS 17909) | cisplatin, velban bleomycin | cul-de-sac, rectosigmoid serosa | chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide) + radiation therapy | |||||

abdominal wall | chemotherapy (same type) | |||||||

(SCS 15756) | cisplatin, velban | lumph nodes | cisplatin/velban, doxorubicin, vinblastine, etoposide | |||||

(SCS 13939) | tumor | chemotherapy (etoposide, cisplatin, doxorubicin) | ||||||

10mos. | radiation therapy | |||||||

2mos. | lumbar vertebrae | |||||||

(SCS 17333) | cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, vincristine, etoposide | omentectomy + paraaortic lymph nodes + radiation therapy | ||||||

(SCS 3146) | BSO | therapy | cecum | chemotherapy (adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin) | ||||

(SCS 23738) | aggressive debulking | cisplatin, doxorubicin, ifosfamide alternating with vincristine, cyclophosphamide and etoposide | ||||||

(SCS 17530) | BSO | etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, vincristine | ||||||

A&W: alive and well; AWD: alive with disease; HT: hysterectomy; LSO: left salpingo-oophorectomy; RSO: right salpingo-oophorectomy; BSO: bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Gross Pathology

The maximum dimension of the tumor in 129 cases with information available was 6-26 cm

(average 15.3 cm) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Largest diameter of ovarian tumors

(129 cases)

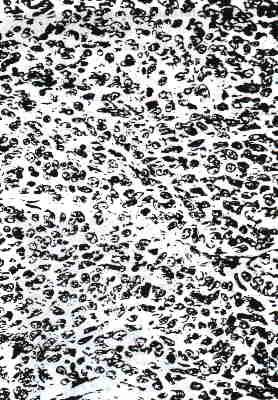

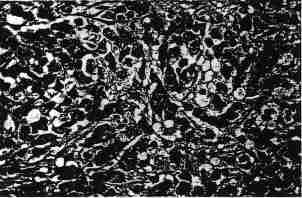

The largest recorded weight was 1,975 g. The external surface of the tumors was recorded as ruptured in 30 cases (20%), which is a minimal figure because reliable information about this feature was not available in many of the cases. The external surface was often described as lobulated or nodular, but it was smooth in many cases. The sectioned surfaces of the tumors were solid (33%) (Fig. 1) or solid with foci of cystic degeneration (67%) with the solid component usually predominating in the latter tumors; two tumors were predominantly cystic. The solid areas were described most often as tan, gray, cream-colored (Fig. 1), or combinations of these colors, but were occasionally yellow. They were frequently lobulated or nodular and were usually soft or fleshy. Occasional specimens were described as firm, granular, or friable.

FIG. 1. Sectioned surface of lobulated, fleshy tumor resembling dysgerminoma

and lymphoma, with focal hemorrhage and necrosis.

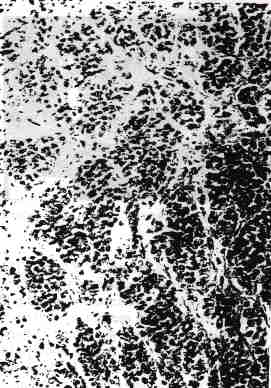

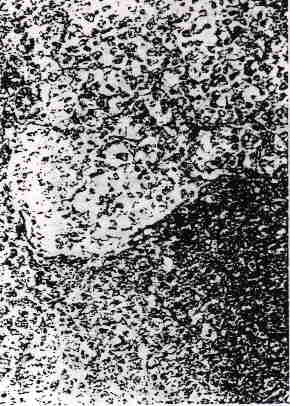

Foci of hemorrhage or necrosis or both were present in slightly over half the cases and were often extensive (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2. Sectioned surface of tumor with extensive hemorrhage and necrosis.

Microscopic Pathology

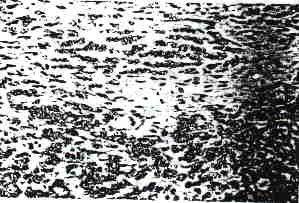

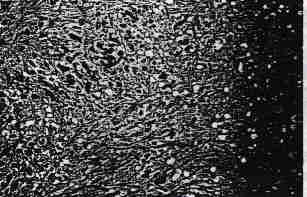

The most common microscopic pattern, which predominated in 77% of the tumors, was a diffuse growth of closely packed cells (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3. Diffuse arrangement of tumor cells with scanty cytoplasm and

small uniform nuclei, many of which have visible nucleoli.

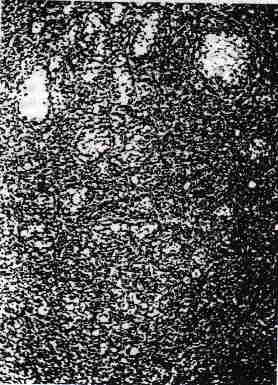

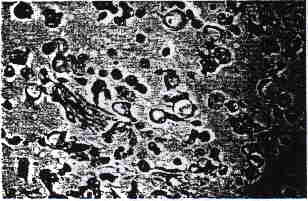

In almost all the tumors with a predominantly diffuse growth, the neoplastic cells also grew in nests (Fig. 4), cords (Fig. 5), clusters (Fig. 5), and singly, and in 23% of the tumors, admixtures of these patterns were present.

FIG. 4. Tumor cells arranged in nests.

FIG. 5. Thin cords of tumor cells and clusters of cells in a fibrous stroma.

The various patterns of growth were interrupted in 80% of the tumors by follicle-like spaces (Figs. 6 and 7), which usually contained eosinophilic fluid but were occasionally empty or, in 3% of the cases, contained basophilic fluid. The follicles were few in 41% of the cases, moderate in number in 29%, and numerous in 10%. They were most often round to oval but were sometimes irregular in shape and additionally exhibited considerable variation in size. Some were tiny (Fig. 6), but others were large and formed microcysts.

FiG. 6. Follicles of varying sizes within a densely cellular neoplasm.

FIG. 7. Two follicles lined by tumor cells with scanty cytoplasm.

Glands or cysts lined entirely or partly by mucinous epithelial cells were present in 18 tumors (12%) (Fig. 8) but were conspicuous in only three of them. In most of the cases the mucinous cells had malignant nuclear features and merged with the small cells, but in four cases glands were lined by benign-appearing mucinous cells that did not undergo transition to the neoplastic small cells.

FIG. 8. Benign-appearing mucinous epithelium (top left) associated with large cell variant of small cell car-cinoma.

Many cells contain intracytoplasmic globules that were eosinophilic.

In three of the cases with mucinous epithelium some of the mucinous cells were of the signet-ring cell type (Fig. 9). The mucinous nature of these cells was confirmed by appropriate special stains in several cases (Fig. 10). In one case there was focal squamous metaplasia of the mucinous epithelium.

FIG. 9. Signet-ring cells with eccentric nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm in a sea of mucin.

FIG. 10. Two glands lined by tumor cells, some of

which have mucicarminophilic cytoplasm (mucicarmine stain).

The most characteristic cell of the neoplasm, present in all but two cases and predominant in most of them, was small and rounded and had scanty cytoplasm (Fig. 3). In 12% of the cases, there were minor foci in which the small cells were spindle shaped (Fig. 11), and in a few such cases, closely packed spindle cells surrounded nests of rounded cells, resulting in a biphasic appearance. The small tumor cells typically had round to oval nuclei that varied minimally in size and shape and were moderately hyperchromatic; in some cases the nuclei of the small cells were swollen and clear. Small nucleoli were often observed (Fig. 3), but prominent nucleoli were rare in the small cells. Small numbers of multinucleated giant cells were present in one case. Numerous mitotic figures were present in all the cases but varied in number from field to field. The count in the stage IA tumors ranged from 16 to 50 per 10 high-power fields.

FIG. 11. Prominent spindle-cell pattern.

Fifty percent of the tumors had a component of varying extent characterized by cells with moderate to abundant amounts of lightly to 'deeply eosinophil-ic cytoplasm (Figs. 12 and 13), which often had a hyaline appearance. This component was minor in 25% of the tumors, moderately abundant in 16%, and prominent, usually being the most conspicuous cell type, in 12%. In two tumors only large cells were present. Large, typically pale eosinophilic in-tracytoplasmic hyaline globules were present in ~60% of the tumors with large cells (Fig. 13) and were usually associated with eccentric displacement of the nuclei (Fig. 8). The nuclei of the large cells were larger and paler than those of the small cells and occasionally were very large and vesicular or clear; they often contained single prominent nucleoli (Fig. 12).

FIG. 12. Large cell variant of small cell carcinoma. The tumor cells have

abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and central nuclei,

many of which have prominent nucleoli.

FIG. 13. Large cell variant of small cell carcinoma. Many of the cells

have eosinophilic cytoplasmic globules. A few cells have eccentric nuclei.

In 15 tumors, cells with clear cyto-plasm were present (Fig. 14); they were minor in 11 of the cases and moderately abundant in four of them. Brightly eosinophilic hyaline bodies were present in a few cases, but they were never numerous.

FIG. 14. Focus of tumor in which the neoplastic cells

have an abundant pale to clear cytoplasm.

The tumors typically had a minor amount of fibrous stroma, but the stroma was moderate in quantity in 17% of the tumors (Fig. 5) and was prominent in 4% (Fig. 15). It was usually composed of relatively acellular fibrous tissue, but in 21% of the cases it was locally or in some cases extensively edematous or myxoid (Fig. 15). An edematous or myxoid stroma appeared to be more common in areas where the tumor cells had abundant cyto-plasm. Exceptionally, the stroma was desmoplas-tic. Vascular-space invasion was frequently observed at the periphery of the tumors and was striking in some of them. Most of the tumors exhibited at least focal necrosis, which was often associated with hemorrhage. In some cases the necrosis and hemorrhage were extensive.

Thirty-three of 36 tumors were immunoreactive for one or more cytokeratins, most consistently for CAM 5.2 (4). Sixteen of 28 tumors were immunoreactive for vimentin, eight of 25 tumors for epithelial membrane antigen, 11 of 19 for neuron-specific enolase, five of seven for parathyroid hormone-related protein (40), four of nine for chromogranin A, and one of 14 for parathyroid hormone (PAB)(4). Twenty-one of 21 tumors, 15 of 15 tumors, and four of four tumors showed negative results on tests for S100, B72.3, and desmin, respectively.

FIG. 15. Small clusters of cells and single cells dispersed in a

prominent myxoid stroma within large cell variant of small cell carcinoma.

Analysis of Prognostic Factors

The stage of the disease was a powerful prognostic indicator. Fourteen of 42 patients (33%) with stage IA tumors were alive without recurrence 1-13 years postsurgery. In contrast, only two of 20 (10%) patients with stage IC disease and four of 62 (6.5%) patients with stages II, III, and IV disease were free of recurrence at last follow-up (p = 0.0009).

To determine whether any other clinical or pathological features of small cell carcinomas might be prognostically important, the presence or absence of a number of them was correlated with recurrence on follow-up of >1 year's duration in patients with stage IA tumors. Table 4, which combines our cases with those in the literature, shows that six of the 10 patients >30 years of age with stage IA tumors (60%) survived without recurrence, in contrast to only eight of the 35 who were <30 years of age (23%) and only one of the 13 who were <20 years of age (8%) (p = 0.12). Of the patients who had pre-operative calcium determinations, four of the six patients with normal levels (67%) were alive without recurrence in contrast to only three of the 10 patients with elevated levels (30%) (p = 0.30). This trend did not appear to be related to the size of the tumor since in both the recurrence and nonrecurrence groups of patients the tumors that were unassociated with hypercalcemia were slightly larger than those complicated by hypercalcemia.

An additional finding in the series as a whole that confirmed the lack of relationship of tumor bulk to hypercalcemia was the almost identical frequency of hypercalcemia in stages I, II, and III cases. There was a suggestion that small size of the tumor in the stage IA group was related to a good prognosis. All three patients with tumors <10 cm in greatest diameter survived without recurrence, in contrast to only three of the 11 patients with tumors 10-14 cm in diameter and only five of the 17 patients with larger tumors (p = 0.09). Only five of the 18 patients with tumors containing large cells (28%) survived without recurrence in contrast to 11 of the 22 patients whose tumors contained no large cells (50%) (p = 0.20). The average mitotic count was almost identical in the tumors of the patients with and without recurrence.

TABLE 4.

Age by decade of patients with stage IA tumors with and without recurrence*

patients | recurrence | recurrence |

There was a trend for a better outcome after a more extensive operation for stage IA tumors. Of the 14 patients who had an operation that included bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy eight (57%) survived without recurrence in contrast to only five of the 21 patients who had a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (23%) (p = 0.075). Of the 17 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, including one who also received radiation therapy, six (35%) survived without recurrence in contrast to five of the 18 patients who received no adjuvant therapy (28%) (p = 0.72). Of the five patients who received radiation therapy (including two who also received chemotherapy) four, including the three who received only radiation therapy, survived without recurrence (p = 0.035).

The only long-term survivor without recurrence whose case is reported in the literature but is not included in our series is a patient with a stage IB tumor, who remained well 58 months postsurgery (50). After operation she received three cycles of chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin, bleomycin, and vinblastine. One patient with a stage IA tumor (16) had a massive recurrence in the broad ligament. After it was removed she received chlorambucil and 5,000 rad delivered to the pelvis. She died 10 years later in an accident and is not known to have had tumor recurrence in the interim.

DISCUSSION

During the 1970s one of us (R.E.S.) collected in a consultation practice 11 examples of an undifferentiated ovarian carcinoma with distinctive histological features and an associated elevation of the serum calcium level in the absence of evidence of bony metastases. One of these cases had been reported as an undifferentiated carcinoma (52). Review of the literature at that time disclosed reports of three additional cases of the same tumor (16,30). At the time of the identification of these tumors as small cell carcinomas, they accounted for half of the known cases of ovarian tumors associated with hypercalcemia. Our subsequent more extensive experience with this tumor has confirmed the three major distinctive clinical features, an occurrence in young women, the presence of hypercalcemia in most of the cases in which the calcium level has been measured before surgery, and a high degree of malignancy. Although the characteristic histologi-cal features of the small cell carcinoma are similar to those originally described, several additional findings have been made, most notably, the frequent presence of large cells with abundant eosin-ophilic cytoplasm and the occasional presence of mucinous elements. Small cell carcinoma occurs in premenopausal women, most of whom are in the reproductive age group. The average age of the patients in the present series of 150 patients was 23.9 years, in the reported cases was 24.5 years, and in the combined group was 24.0 years. The oldest patient whose case has been reported under the designation of small cell carcinoma was 55 years old, but it is questionable whether her tumor was a carcinoma of the type we are reporting (1). The youngest patient in the present series was a 9-year-old girl, whose case was reported in detail elsewhere (40). The age distribution according to decade in our series is presented in Table 1.

The clinical presentation almost always has been similar to that of patients with ovarian cancer in general; in the present series, symptoms related to hypercalcemia were present in only four patients, one of whom underwent an unnecessary neck exploration because of the hypercalcemia and the initial failure to detect an ovarian mass. A similar case has been reported (16). Tumors with only small cells were associated with hypercalcemia in 70% of the cases in contrast to 57% for tumors with a large cell component, although this difference is not statistically significant. Small cell carcinoma has accounted for ~60% of the known cases of ovarian tumors associated with hypercalcemia (Table 5). In addition to the 49 cases in our series, there are 13 other reported cases with hypercalcemia (1,10,17, 26,30,61,66,67).

TABLE 5.

Ovarian tumors associated with hypercalcemia*

arising from dermoid cyst | ||

endometrioid carcinoma | ||

Ovarian tumors of other types reported to have this association are listed in Table 5 (2,5,8,11-14, 24,25,27-29,32,35,36,39,44,45-48,51,52,56-57,60,62-64,68). Dysgerminoma is the only one of these tumors that typically occurs in an age group similar to that of patients with small cell carcinoma. Accordingly, although the frequency with which hypercalcemia is associated with various ovarian tumors is difficult to establish from analysis of a consultation series and isolated case reports in the literature, a small cell carcinoma is a serious diagnostic consideration in a patient between 9 and 45 years of age with otherwise unexplained hypercalcemia. The pelvis should be investigated in every young woman with unexplained hypercalcemia to avoid overlooking an ovarian cancer.

Since accrual of cases for this study was completed, we have seen three small cell carcinomas of the hypercalcemic type from three sisters; one of them is case 3 in the series of Peccatori et al. (50). This finding is notable because two of the patients in the present series were cousins (also included in the series of Ulbright et al. [67]), and two others were a mother and daughter. These occurrences indicate that this rare tumor is familial in some cases.

At the time of laparotomy, small cell carcinoma is almost invariably unilateral. The contralateral ovary is occasionally involved as part of abdominal spread of the tumor, but there were only two cases in our series in which there were bilateral primary tumors, and one similar case has been reported (50). Remarkably, all three sisters that we saw with this tumor had bilateral tumors. Extensive spread beyond the ovary is present in approximately half of the cases at the time of presentation.

On gross examination the primary tumors are usually large, predominantly solid, soft, and tan-gray to creamy white and often contain areas of necrosis and hemorrhage, which may be extensive. The tumor may closely resemble a dysgerminoma or malignant lymphoma on gross inspection. Cystic degeneration is common, but only two of our tumors were predominantly cystic. One tumor in the literature, however, was a unilocular cyst (31).

The differential diagnosis of ovarian small cell carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type includes numerous other tumors that occur in young women. The tumor is often confused with either adult granulosa cell tumor (AGCT) or, particularly in cases with a Significant component of large cells, juvenile granulosa cell tumor (JGCT) (69). An association with hypercalcemia provides strong evidence against the diagnosis of both forms of GCT, which have not been reported to have this association. Conversely, estrogenic manifestations, which have not been associated with small cell carcinoma, favor a GCT. At laparotomy, spread beyond the ovary, which is present in 50% of cases of small cell carcinoma, is much less common with either form of GCT. The typical fleshy, tan to white appearance and the frequently extensive necrosis of small cell carcinoma would be unusual for either type of GCT. The diagnosis, however, must be made on the distinctive microscopic features of the tumors. The nuclear features of small cell carcinoma do not suggest the diagnosis of an AGCT, which, in contrast to the former, has pale, often grooved nuclei. Moreover, the mitotic activity in small call carcinoma exceeds that of the great majority of AGCTs. The presence in some small cell carcinomas of mucinous epithelium argues strongly against the diagnosis of either form of GCT, although one AGCT associated with mucinous epithelium has been reported (54). Finally, various distinctive patterns of AGCT, including the formation of Call-Exner bodies, are not seen in small cell carcinoma.

The young age at which small cell carcinoma occurs, its very common content of follicle-like structures, and the presence in many cases of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm may lead to the misdiagnosis of a JGCT. Most small cell carcinomas, however, have a major component and in almost all the cases at least a minor component of cells with scanty cytoplasm, which are not a feature of most JGCTs. In addition, the cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm that are present in JGCT and in small cell carcinoma typically differ in appearance. In small cell carcinoma the nuclei are frequently eccentric with hyaline globules in the cyto-plasm, whereas the nuclei are typically central in JGCT, and cytoplasmic globules are rare.

A small cell carcinoma, with an extensive diffuse pattern, may simulate closely malignant lymphoma. The presence of follicle-like structures is highly characteristic of small cell carcinoma and an unusual feature of malignant lymphomas. Most important, the cytologic features of the neoplastic cells are not similar to those of any type of malignant lymphoma. Immunohistochemical staining is helpful in the differential diagnosis in difficult cases, but it is rarely necessary if careful attention is devoted to the histological and cytological features of the tumor.

Because of the young age of the patients and the highly malignant appearance of the tumors, the diagnosis of a primitive germ cell tumor, specifically dysgerminoma, embryonal carcinoma, or yolk sac tumor, is often considered by pathologists not familiar with the distinctive features of small cell carcinoma. The cells of small cell carcinoma, however, do not have the characteristic clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm of the dysgerminoma cell or the lymphocytic infiltration of the stroma of that neoplasm. The extremely rare embryonal carcinoma almost always has glandular and papillary patterns, which are not features of small cell carcinoma. Yolk sac tumor has a variety of characteristic patterns, including reticular and papillary, which are not a feature of small cell carcinoma, and it is rare in yolk sac tumors to have a diffuse growth of small cells with scanty cytoplasm (79). Although the large cell variant of small cell carcinoma often contains ill-defined pink intracytoplasmic globules, it occasionally contains brightly eosinophilic hyaline bodies similar to those seen in many yolk sac tumors, but such structures are nonspecific diagnostically and occur occasionally in many ovarian tumors (6,79).

Small cell carcinomas may be confused with diverse other small cell malignant tumors that occasionally affect the ovaries of young women. These tumors include primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) (3,37), primary (37) and metastatic neuroblastomas (72), metastatic round cell sarcomas (75,76), and intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor (70). Rarely, follicle-like structures may be seen in primary or metastatic neuroblastomas and in PNETs, enhancing their resemblance to small cell carcinoma. However, the presence of so-called Homer Wright rosettes and bands of neurofilaments in neuroblastomas and the presence of true rosettes in PNETs usually facilitate the diagnosis. Also, primary neuroectodermal tumors are often associated with teratomatous elements, in contrast to small cell carcinoma. Finally, the distinctive immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of PNET and small cell carcinoma differ. We have seen one case of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma and one case of Ewing's sarcoma metastatic to the ovary in which initial consideration was given to the diagnosis of a small cell carcinoma (76). In such cases clinical features almost invariably enable one to make the correct diagnosis, although rarely the primary site of a metastatic tumor is not known by the pathologist, increasing the likelihood of an error.

Malignant melanoma metastatic to the ovary is rarely composed of small cells with scanty cytoplasm forming follicle-like spaces, leading to a misdiagnosis of small cell carcinoma (65,77). The history of a primary malignant melanoma and immunohistochemical staining of the ovarian tumor for S-100 protein and HMB-45 are important in establishing the diagnosis in these cases. Immunohistochemical staining was also decisive in one unre-ported case we saw of primary malignant melanoma of the ovary that contained small cells and follicle-like spaces.

A recently described small cell tumor that may affect the ovary and be confused with small cell carcinoma is intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT). All three examples of prominent ovarian involvement by this neoplasm occurred during adolescence (70). The ovarian involvement was bilateral in two of the three cases, in contrast to the rarity of bilaterality of small cell carcinoma. Although small cell carcinoma may have an insular pattern, it is generally absent or only focal, whereas in DSRCT, discrete nests of tumor cells are characteristic. Additionally, DSRCT lacks follicles and typically has a prominent desmoplastic stroma, which is either absent or only focal in small cell carcinoma. If any difficulty in the distinction of DSRCT and hypercalcemic small cell carcinoma remains on the basis of the examination of routinely stained sections, immunohistochemical examination should be diagnostic, because staining of the DSRCT for desmin is not a known feature of small cell carcinoma. Although experience with staining of DSRCT for desmin is limited to six cases--two in the literature (38) and four in this series--all of them gave negative results.

Finally, small cell carcinomas of the pulmonary type primary in the lung (74) or occasionally in other sites (22,71) may metastasize to the ovary, and tumors of this type may also be primary in the ovary (22). Indeed, some authors have interpreted small cell carcinoma of the ovary that is usually associated with hypercalcemia in young women as small cell carcinoma of the pulmonary type (1). Although the staining of some of our small cell carcinomas of the hypercalcemic type for chromogranin A might seem to support this contention, it is of note that two of five Sertoli cell tumors studied by Aguirre et al. (4) also stained for chromogranin. In the rare cases of ovarian metastasis of small cell carcinomas of the pulmonary type (23), the clinical findings, including age of the patient and demonstration of an extraovarian primary tumor, are often helpful, but if the tumor presents as an ovarian mass without knowledge of a primary tumor and has the follicle-like spaces seen in metastatic tumors of many types (78), the pathologist may misdiagnose primary small cell carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type. Most small cell carcinomas of the pulmonary type, whether primary or metastatic, however, occur in an older age group than does small cell carcinoma associated with hypercalcemia. Other differences between the two forms of primary ovarian small cell carcinoma have been discussed in detail elsewhere (22).

The cell lineage of small cell carcinoma remains uncertain. Ultrastructural (19,43) and immunohistochemical investigations (4) have so far failed to uncover any specific feature to identify the cell type of this tumor. The most consistent and striking ultrastructural finding has been the presence of abundant dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum with the formation of large vesicles filled with homogeneous, granular (proteinacious) material of variable density (19,43). A prominent ultrastructural finding in the large cell variant of small cell carcinoma is the presence of frequently prominent microfilaments, which are often paranuclear, sometimes forming striking whorls in cases in which the cells have globular cytoplasm on hematoxylin and eosin examination (1,19,38,67). In one series of six small cell car-cinomas, three of them contained "scattered" structures that were interpreted as being dense core granules of the neuroendocrine type (1). The illustrations provided are not convincing, however, and these structures could be primary or secondary lysosomes (59). A few structures interpreted as dense core granules were also described in one case in an abstract (26).

Most ovarian cancers are of surface-epithelial, germ-cell, or sex-cord origin, and the small cell carcinoma may belong in one of these three categories. Since carcinomas of surface-epithelial origin reach their peak age incidence after menopause and are uncommon before the age of 40 years, it is unlikely that small cell carcinomas belong in that category. Additionally, in our experience with >1,000 surface-epithelial carcinomas, we have not seen a pattern resembling that of small cell carcinoma. The presence of mucinous epithelium in 12% of our small cell carcinomas and in as many as 37% of the cases in another report (26) raises the possibility of an association with mucinous tumors with foci of anaplastic carcinoma (53), but the tumors of the latter type have not contained areas resembling typical small cell carcinoma. Also, mucinous epithelium may be found in tumors of germ cell origin, heterologous Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors (73), and surface-epithelial carcinomas. Surface-epithelial carcinomas of the ovary differ immunohistochemically from small cell carcinoma inasmuch as the former have been reported to be almost uniformly reactive for epithelial membrane antigen, whereas only one-third of our small cell carcinomas stained for this antigen.

Primitive germ cell tumors occur in an age group that is generally similar to that of small cell carcinomas, although the former are encountered much more frequently than small cell carcinoma during the first decade. A germ cell nature of small cell carcinoma has recently been proposed on the basis of finding areas resembling it in a single testicular germ cell tumor (67). An argument against such an interpretation, however, is the absence of other evidence of germ cell neoplasia in association with small cell carcinoma of the ovary and our failure to observe areas of small cell carcinoma in examination of >600 malignant ovarian tumors of germ cell type.

The age distribution of small cell carcinoma suggests a sex cord cell origin. However, a highly malignant form of JGCT seems unlikely because JGCT occurs much more commonly in the first decade (69). The various patterns that may be seen in small cell carcinoma, including follicular, cord-like, insular, and diffuse, may be seen in AGCTs. Immunohistochemical study of these neoplasms, however, has shown striking differences between small cell carcinoma and GCTs, particularly those of the adult type. Staining for cytokeratin is seen in both tumors but is encountered more frequently in small cell carcinoma, and when found in GCTs it is present in a greater number of the neoplastic cells. Epithelial membrane antigen is found in one-third of small cell carcinomas, but it is absent from GCTs. Vimentin is usually present in GCTs but is seen in only ~55% of small cell carcinomas. There are also contrasting results in the staining of these two neoplasms for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase. The presence of mucinous epithelium in these neoplasms is inconsistent with a GCT, if the one unusual reported example with mucinous epithelium (54) is excluded. Finally, we have not seen areas resembling small cell carcinoma in either granulosa or Sertoli cell tumors.

A variety of investigations have been performed to identify the nature of the substance secreted by ovarian small carcinoma that results in hypercalcemia. In several cases in which the serum parathormone level has been measured, it has been negative (16,18,30). A parathormone-like substance was found in one case (10). In another case, attempts to recover parathormone or parathormone-like substance from the tumor were unsuccessful (18). In one of the cases included in the present series, Aguirre et al. (4) found that rare tumor cells stained weakly with an antibody against parathormone, a staining pattern that was considered nonspecific. Abelet et al. (1) found strong immunoreactivity for parathormone in three of six cases, but McMahon and Hart (43) were unable to establish parathyroid hormone immunoreactivity with the use of a different polyclonal antibody reagent on six small cell carcinomas. Most recently, investigations have been performed to ascertain the possible role of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) (20,41) in the genesis of the hypercalcemia in these cases. Using immunocytochemistry, Burton et al. (15) found PTHrP throughout the cytoplasm of most tumor cells in one case of small cell carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type, and Matias-Guiu and colleagues (42) found that five of seven tumors included in the present series were immunoreactive for PTHrP. The normal levels of serum calcium in two of these cases, however, cast some doubt on the role of PTHrP in causing the hypercalcemia in these cases. Moreover, this substance is apparently widely distributed among normal tissues and neoplasms (20).

The optimal therapy of small cell carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type remains unclear because inadequate staging is common and there were a variety of therapeutic approaches in many of the cases analyzed in this report. Obviously, like any other ovarian cancer, small cell carcinoma should be staged carefully.

Despite the deficiencies in some of the data in the present series, there is suggestive evidence that some forms of therapy may be superior to others. Although the rate of bilaterality of this tumor is extremely low at the time of presentation, those patients with stage IA tumors who were treated by an operation that included bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy fared considerably better than those treated by unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, although the difference in survival and recurrence did not reach the significance level of 0.05. There was no clear-cut evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy improved the prognosis in the stage IA cases, although the variety of regimens used made it difficult to evaluate individual regimens. Although only five patients received adjuvant radiation therapy, the four survivors in that group suggest that it may have a role in the adjuvant therapy of this tumor. Patients who received radiation had a significantly better outcome (p = 0.035).

Despite occasional striking temporary responses to therapy, the treatment of recurrent tumors and tumors higher than stage I has been generally disappointing. However, cases 4, 5, 6, and 7 in Table 2, and one case in the literature in which the patient lived, apparently disease free, for 10 years after radiation therapy and chlorambucil treatment for recurrent tumor (16), indicate that some patients with recurrent or high-stage disease respond well to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both. The overall experience with radiation therapy in both stage IA and higher stage cases suggests that this form of therapy may have a greater role in the treatment of small cell carcinoma than it does for surface epithelial cancers of the ovary. Since the serum calcium level typically rises when the small cell carcinoma recurs, it can be used as a marker in monitoring the course of the disease. It may even be a useful marker in those cases in which the serum calcium level was not elevated initially, as we have seen recently a small cell carcinoma, not included in this series, in which the calcium level was initially normal and became elevated as the first manifestation of recurrence.

Acknowledgements: Because of space constraints we will not list the numerous pathologists and clinicians who helped us by providing material and information on these cases, but we would like to express our thanks to them here. We specifically acknowledge those who provided detailed information for the cases summarized in Table 2: J.H. Habermann, M.D., Joplin, Missouri, and Herbert J. Schmidt, Kansas City, Missouri (case 1); Arno A. Roscher, M.D., Granada Hills, California, and Carole Hurvitz, M.D., Los Angeles, California (case 2); John C. Merenkov, M.D., Elmhurst, Illinois, and Thomas E. Dolan, M.D., Des Plaines, Illinois (case 3); Nancy Lammert, M.D., and Guy Benrubi, M.D., Jacksonville, Florida (case 4); George B. McAdams, M.D., Hartford, Connecticut (Case 5); T. Sohotra, M.D., and Malcolm Idelson, M.D., Poughkeepsie, New York (Case 6); and Elvio G. Silva, M.D., Houston, Texas (Case 7). Dr. Thomas Abbott of Salt Lake City, Utah, kindly obtained further information on the first reported patient with this tumor (16). Finally, we are grateful to Dr. Philip B. Clement for his critical review of the text and to Dr. Judith Ferry for her help with statistical analysis.

Note added in proof: We have recently seen a tumor of this type in a seven-year-old girl.