While scientific progress in the past two centuries has enriched our understanding of and command over the natural world at a near inconceivable pace, it has simultaneously contrived in Western man a near-hegemonic biological positivist conception of ourselves and of our ultimate purpose in this universe -- one that offers none of the timeless consolations afforded us by the mythologies and religions of prior times. Moreover, all this vaunted progress should, according to the implications of the Enlightenment, have made us a kindler, gentler, and more humane species. Yet, the events of this past century -- World Wars and atomic bombs, ethnic cleansings and the Holocaust -- indicate that, while better nutrition may have made our bodies taller and our lives longer, we seem only to have become nastier and more brutish. (As T.S. Eliot, Modernity's poet, aptly put it, "Between the idea and the reality falls the Shadow.")

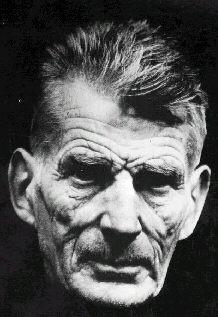

Like the writings of his philsophical and literary predecessors (Friedrich Nietzche and Franz Kafka), his artistic contemporaries in the French existentialist school (Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre), and his most direct aesthetic descendant (Tom Stoppard), Samuel Beckett's works explore this crisis of meaning in the Western world. Throughout his essays, poems, and plays, Beckett combines the existentialism of his adopted home country of France with the innate Irish gift for combating despair with biting humor and sheer absurdity.

The best example of Beckett's unique variant of existentialism is his most famous play, Waiting for Godot. The story follows the actions, or non-actions, of two men -- Vladimir and Estragon -- as they incessantly wait for the promised arrival of one Mr. Godot. The two friends bide the time talking, playing games, and becoming increasingly more frenetic about the tardiness of their appointment, until the very purpose of their waiting, or even of their existence, becomes one of crushing magnitude.

No questions are answered, and no fears assuaged, by the conclusion of the play. On the contrary, the absurdity of Vladimir and Estragon's conversations grows increasingly more like thin, fragile ice over a bottomless chasm. Simultaneously hilarious and utterly chilling in its depiction of man's defenses against the void, Waiting for Godot richly deserves the acclaim it has received around the world.

The Samuel Beckett Endpage at UC-Santa Barbara

Beckett, Samuel (1906-1989), Irish-born poet, novelist, and leading

dramatist of the theater of the absurd. Beckett won the 1969 Nobel Prize

for literature. In his novels and plays alike, Beckett focused on the

wretchedness of living in an attempt to expose the essence of the human

condition, which he ultimately reduced to the solitary self, or to nothingness.

His influence on subsequent dramatists, particularly those who followed him

in the so-called absurdist tradition, was significant, and the impact of

his prose works was considerable.

Beckett was born in Foxrock, near Dublin. After attending a middle-class

Protestant school in the north of Ireland, he entered Trinity College, Dublin,

where he earned an A.B. in Romance languages (1927) and later an M.A. (1931).

Between degrees, he spent two years teaching in Paris. At the same time he

continued his study of French philosopher René Descartes and wrote

his critical essay Proust (1931), which laid the philosophical foundation

for his life and literary work. Significantly, he also became acquainted

with Irish novelist and poet James Joyce.

From 1932 to 1937 Beckett wrote, traveled frequently, and held various

jobs. His income was supplemented by an annuity from his father, whose death

in 1933 shocked him profoundly. In 1937 Beckett settled permanently in Paris,

except during World War II (1939-1945), when, as a member of the Resistance,

he fled the Nazi secret police, known as the Gestapo. In unoccupied southern

France, Beckett used his evenings to write the novel Watt (not published

until 1953).

Back in Paris after the war, Beckett created four major works: his trilogy

Molloy (1951; translated 1955); Malone meurt (1951; Malone Dies, 1956), and

L'innominable (1953; The Unnamable, 1958), novels that Beckett considered

his greatest achievement; and the play, En attendant Godot (1952; Waiting

for Godot, 1956), which most critics regard as his masterpiece. Other major

works include the plays Fin de partie (1957; Endgame, 1958), Krapp's Last

Tape (1959), Happy Days (1961), Play (1964), Not I (1973), That Time (1976),

and Footfall (1976); the narrative prose works Murphy (1938; translated 1957),

and Comme c'est (1961; How It Is, 1964); and the verse collections Whoroscope

(1930) and Echo's Bones (1935). The Collected Works of Samuel Beckett (22

vol.) was published in 1977. In 1995 Eleutheria: A Play in Three Acts was

published.

Beckett's bizarre world is explored in novels, short stories, poetry, and scripts for radio, television, and film. But he is best known for his work in the theatre. His most famous play, Waiting For Godot, opened at a tiny theatre in Paris in 1953 and went on to become one of the most important dramatic works in this century. The strange atmosphere of Godot, in which two tramps wait on what appears to be a desolate road for a man who never arrives, conditioned audiences to following works like Endgame, Happy Days, and Krapp's Last Tape.

Beckett's drama is most closely associated with the Theatre of the Absurd. He employs a minimalistic approach, stripping the stage of unnecessary spectacle and characters. Tragedy and comedy collide in a bleak illustration of the human condition and the absurdity of existence. In this way, each work, from the lengthy productions (Godot, Endgame) to the very brief (Ohio Impromptu, Catastrophe) to the despairing mologues (Rockaby, A Piece of Monologue), serves as a metaphor for existence and an entertaining philosophical discussion. Although Beckett dissociated himself from the post World War II French existentialists, his works cover much of the same ground and ask similar questions.

-S.