The United States' Involvement with Dokdo Island (Liancourt Rocks):

A Timeline of the Occupation and Korean War Era

The majority of information provided on this webpage was obtained from File 322: "Liancourt Rocks", from the Seoul Embassy Records, Record Group 84, the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Other sources include research by Cheong Sung-hwa, the United States Air Force Historical Research Agency, and internet media sources.

1945

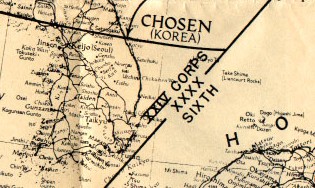

This map of the initial occupation boundaries was found among a collection of the first Instructions (SCAPINs) issued by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) in September 1945.

|

September 1945: A map generated by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) in September 1945 shows the initial

setup of the occupation boundaries of different US military commands. Dokdo is shown within the US Sixth Army's occupation zone,

and outside of the Korea-based US XXIV Corps' zone. The process by which SCAP determined these zones is unknown.

9/27/45: In an early instruction to the Government of Japan, SCAP states that Japanese should not be allowed to

approach within 12 miles of Dokdo.

1946

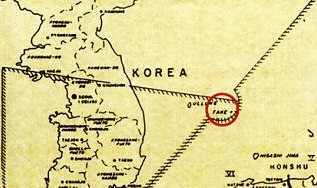

This map accompanied SCAPIN 677, which delimited the Japanese territorial sphere to

the exclusion of Dokdo, and thereby creating the ´MacArthur Line´.

|

1/29/46: SCAPIN 677 is issued. This instruction defined the territorial boundaries of Japan, explicitly excluding

Dokdo, cited as "Liancourt Rocks (Take Island)". The occupation boundaries were therefore replaced by a new boundary, the so-called ´MacArthur Line´, which placed Dokdo within the Korea-based XXIV Corps´s area of responsibility. This policy of excluding Dokdo from Japanese fishing areas and

administrative control was sustained throughout the occupation of Japan. Again, why and by what process the General Headquarters

of SCAP decided to exclude Japanese involvement with Dokdo throughout the occupation is not known for certain. It is thought that perhaps SCAP GHQ used Japanese maps published by the Imperial Army to determine that Dokdo was outside Japan´s control.

6/22/46: SCAPIN 1033 is issued. This instruction extended the allowable areas for Japanese fishing, but again

explicitly stated that Japanese were not to approach within 12 miles of Dokdo.

1947

4/16/47: According to Korean eyewitnesses, aircraft used the Dokdo islets as a bombing target on this date. This is

the earliest known account of the island used as an aerial target range.

9/16/47: SCAP issues Instruction #1778. Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo) is designated as a bombing range in this instruction

to the Japanese government. It mentions that inhabitants of "all ports on the west coast of the island of Honshu north to

the 38th parallel" in addition to Oki Island were to be notified prior to each use of the range.

It is still not clear why Japanese were warned of the use of the island when they were not allowed to be anywhere near the island, as per SCAPIN 1033. It is also not known if the occupation authorities in Korea knew about this order from SCAP, or if they had similarly warned Koreans.

The American use of Dokdo as a bombing range was part of a larger, world-wide US strategic initiative that came about with the formation of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) under the newly-minted United States Air Force in 1947. The new "Strategic Air Command Rotation Program" called for SAC bomber Groups to rotate through the Far East airbase on Okinawa on extended temporary duty deployments in an effort to keep aircrews "trained up" in operations involving forward deployments in case of war. The rotation program began at this time, and continued for decades. Dokdo was one of many islands throughout the Pacific that the US Air Force used in the late 1940s as bombing target in order to keep their pilots trained in bombing and strafing. SCAP General Headquarters evidently obliged the Air Force´s needs by officially designating the island as a bombing range.

9/23/47: A monograph entitled, Part IV of "Minor Islands Adjacent to Japan Proper; Minor Islands in the Sea of

Japan", a treatise drafted by the Japanese Foreign Ministry, is sent from the Diplomatic Section of SCAP to the US State Department in

Washington. This monograph was the Japanese argument for sovereignty over both Ullungdo and Dokdo. Copies of the monograph

were distributed to occupation authorities when the Japanese Foreign Ministry petitioned to SCAP over Japanese sovereignty concerns in

June of this year. Upon receipt of this document, the State Department noted that it would be useful for future reference in case

the disposition of the islands became an issue in a peace treaty with Japan.

In fact, the opinions

stated in the Japanese monograph seem to have had a major influence on U.S. officials in the State Department´s Office of Northeast

Asian Affairs. In particular, Directors Robert A. Feary and Kenneth T. Young Jr, and the head of the Diplomatic Section of SCAP,

William J. Sebald, would later offer opinions that were very similar to statements in this 1947 document. As it turned out, the

State Department gave a memorandum to the Korean Ambassador in Washington on August 10, 1951 which was based on soley on the information

in "Minor Islands in the Sea of Japan". The San Francisco Peace Treay was signed between Japan and the former Allied

Powers in order to formally end the Pacific War and was to be pertinent to the sovereignty of Dokdo, as the treaty would deal with the

territorial definitions of Japan and Korea. Another interesting fact about "Minor Islands in the Sea of Japan" is that the Korean government seemed not to have even known of the existence of this Japanese petition until decades later.

1948

3/25/48: In a bombing exercise that forshadows the events of the June 8, 1948 bombing incident, fourteen B-29s of the 22nd Bombardment Group flying out of Kadena Air Base on Okinawa use Dokdo as a bombing target. The bombing mission was reported in US Air Force documents as a high altitude, formation-bombing mission that achieved "excellent results". The 22nd Bombardment Group soon left Okinawa for the continental United States, being replaced by the 93d Bombardment Group, which started arriving in May 1948 for a three-month deployment to the Far East. The 93d was the first Bombardment Group to do so under the SAC Rotation Program. Although the exact bomb-load used by the fourteen B-29s in this exercise is unknown, Air Force documents show that for the month of March 1948, the 22nd Bombardment Group expended hundreds of 100-pound and 500-pound General Purpose bombs, sixty 1,000-pound bombs, and 13,900 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition. No deaths or injuries are known to have resulted from this bombing, nor is it evident that the media or public were aware of this exercise at the time.

6/8/48: Twenty-one B-29s of the US Air Force´s 93d Bombardment Group flying out of Kadena Air Base on Okinawa use Dokdo as a

bombing target, dropping seventy-six 1,000-pound AN-M-65 bombs, killing a number of Korean fishermen who were at the islets. U.S.

occupation forces in Korea issued a press release on June 17 stating that the B-29 crews could not see the Korean fishing boats at Dokdo,

and that boats were discovered only after examining photographs taken 30 minutes after the bombing. (In an interview in 2002, a former bombardier of the 93d BG stated that he had seen fishing boats through his bomb-sight while flying over the target

area during a bombing run on a small island on which he dropped bombs in the summer of 1948).

The government of the

Republic of Korea stated in 1955 that around 30 Korean fishermen were killed in this incident, while survivors have

said that many more, perhaps hundreds, died. Surviving fishermen and other residents of neighboring Ullung Island reported

that they had been unaware that the island was a designated a bombing range.

6/15/48: In a radioed message, the Commanding General of USAFIK (United States Army Forces in Korea) witholds approval for any bombing practice in the area of Dokdo until further notice. This message is sent to the Commanding Generals of the Fifth Air Force, the Far East Air Force (FEAF), and the Commander-in-Chief of the Far East (CINCFE). View document

This radio message seems to suggest that authorities in Korea (not Japan) exercised operational authority over Dokdo.

6/16/48: The U.S. Fifth Air Force replies to authorities in Korea, stating that their Headquarters is closing Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo) to all bombing practice.

6/23/48: The Korean daily, Choson Ilbo reports that US authorities have issued a statement declaring that Dokdo would no longer be used as a bombing range.

6/24/48: The Commanding General of USAFIK, Major General William F. Dean writes to CINCFE asking for a complete halt to all bombing off the East Coast of Korea, including Dokdo. He argues that Dokdo is a vital fishing ground for the Korean nation, and that it is the "principal source of livelihood for 16,000 fishermen and their families living on Ullung Do and nearby islands who own or operate 456 boats in this area." He adds that Dokdo is essential in producing enough seafood to meet the nutritional requirements of Korea. View document

6/29/48: Lieutenanat General John R. Hodge of USAFIK writes to CINCFE, concurring with General Dean´s decision, stating: "It is highly desirable that this area be available to Korean fishermen. Favorable action will do much to counteract the unfavorable conditions created by the recent bombing."

8/5/48: The Office of the Political Advisor of SCAP receives a document, the subject being a "Request for Arrangement

of Lands Between Korea and Japan" from the "Patriotic Old Men´s Association" of Seoul, Korea. The petition was

an attempt at explaining Korea´s sovereignty over Ullungdo, Dokdo (cited as "Docksum"), the fictitious island of

"Parangdo", and Tsushima Island. Although supposedly from a private organization, the petition followed ROK President Syngman

Rhee (Yi Seung-man)´s thinking regarding disputes with Japan.

The petition was the only

explanation of Korea´s claim to sovereignty over Dokdo that was available to U.S authorities until the beginning of the

negotiations for the San Francisco Peace Treaty. While it did attempt to explain the irregularities of Japan´s supposed

incorporation of Dokdo in 1905, the argument for Dokdo was included with an angry demand for Korean sovereignty over Tsushima and

concerns over (what turned out to be) an imaginary island named "Parangdo". The petition´s seeming lack of

seriousness and its vengeful tone (harking back to the punitive reparations of the Versailles Treaty of 1919), in addition to the fact

that it had come from a private organization and was not a direct policy statement from the ROK Government, had most likely jaundiced

American views towards the Korean argument for sovereignty over Dokdo. It is at least quite clear that this Korean petition (view document) was not at all as influential to U.S. decision-makers as was the Japanese Foreign Ministry´s 1947 monograph.

9/13/48: The Fifth Air Force writes its monthly update on bombing and gunnery ranges, noting that "Liancourt Rocks Bombing and Gunnery Range" (Dokdo) has been closed permanently by the Commanding General, Far East Air Forces. View document

1949

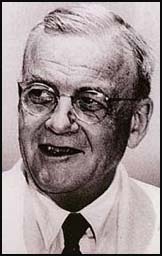

The Head of the Diplomatic Section of SCAP, William J. Sebald (center) enjoys some

conversation with Consultant to the U.S. Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles (left) and Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida at a

reception in Tokyo on January 31, 1951. Sebald made statements supporting Japan´s claim to Dokdo, but played down any American

stance on the issue by 1954.

|

11/14/49: The Acting Political Advisor in Japan, William J. Sebald sends a note to Consultant to the U.S. Secretary of

State John Foster Dulles about American security concerns in regards to the territorial provisions of the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

In it, he states that Japan´s claim to Dokdo is "old and appears valid", adding that "security considerations

might render the provision of weather and radar stations on these islands a matter of interest to the United States".

Sebald´s views on Dokdo´s sovereignty influenced the U.S. Secretary of

State John Foster Dulles´ opinions in his negotiations with the Koreans over Dokdo in 1951. As the San Francisco Peace

Treaty was largely a creation of John Foster Dulles, his views shaped the final draft of the Peace Treaty. (However, as we will

see, Sebald would later [in 1954] deny any U.S. recognition of Japanese ownership of Dokdo). It is interesting to note that

American interests with regard to Dokdo in 1949 mirrored Japan´s interest in Dokdo in 1905, in that both nations wanted to use the

islets in a military capacity. This might also help explain Sebald´s view that Dokdo was a Japanese island, as he might have

thought that Japan was willing to turn the islets into a military facility for use by U.S. forces. See early U.S. State Department views concerning Dokdo.

1951

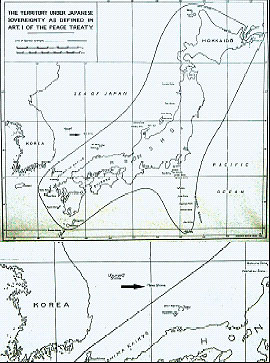

During the peace treaty negotiations, the British Commonwealth proposed the exact

delimitation of Japan´s territorial sphere by latitude and longitude in order to avoid territorial disputes, as depicted in this

April 7, 1951 map that the British sent to the U.S. State Department. Dokdo was placed outside of Japan´s territorial

sphere. However, the American opinion that Japan should not be "fenced in" prevailed, resulting in decades of conflict

over Dokdo between Korea and Japan.

|

3/12/51: The British Foreign Ministry informs the United States of its views on the peace treaty with Japan. The

British, after consulting with the Commonwealth nations (Australia, Canada, New Zealand), proposed that Japanese territory be defined as

the four main Japanese islands and a few adjacent minor islands, as suggested in the Potsdam Declaration. The British proposal (as

suggested by New Zealand) was to have Japanese territory and territorial waters be defined by an exact delimitation in latitude and

longitude. The British Commonwealth nations were concerned about territorial disputes with Japan, and insisted on this item.

The U.S. State Department later dissuaded the British of this idea.

If the British proposal had actually been adopted in the final draft of the peace treaty, it could very

well have prevented the territorial dispute over Dokdo between Korea and Japan. It is quite certain, considering the placement of

Dokdo in a map drawn up by the British team and sent to the Americans on April 7, that this proposal would have placed Dokdo outside of

Japan´s territorial sphere.

5/3/51: After meeting in conference, British and U.S. negotiators arrive at a joint draft of the peace treaty. In

regards to territorial definitions of Japan, the U.S. team succeeded in persuading the British to drop their idea of delimiting Japanese

territory by latitude and longitude, as such a plan would have "psychological disadvantages of seeming to fence Japan in by a

continuous line around Japan." Instead, the U.S. got the joint draft to define Korean territory in the East Sea/Sea

of Japan as Chejudo (Quelpart), Kommundo (Port Hamilton), and Ullungdo (Dagelet). Thus, the 1947 Japanese petition for ownership

of Ullungdo was denied by the Americans; however, Dokdo was not included in (or excluded from) any territorial definition of Korea or

Japan in the final draft of the San Francisco Peace Treaty (signed on September 8, 1951, and went into effect in April 1952). The

U.S. State Department thus effectively obviated the previous five years of American policy set by the SCAP Government Section that

explicitly excluded Dokdo from the Japanese territorial sphere.

Although the British Foreign Ministry did not know that both Korea and Japan claimed Dokdo, the American

State Department did know of the competing claims, after having received petitions for the ownership of Dokdo by both countries

(in 1947 and 1948). The eventual result of the wording of Article 2(a) in the peace treaty was that Japan would later claim that

all islands in the East Sea/Sea of Japan that were not specifically mentioned in the definition of Korean territory (such as Dokdo) could

be considered Japanese. The Koreans would later make a rather pertinent and obvious objection to this interpretation by pointing out that this meant that numerous other Korean islands in the same area (Maemuldo, Hongdo, Yokjido, Kojedo, etc) would also belong to Japan, as these islands were also not mentioned in Article 2(a). The U.S. State Department´s reasoning for eventually leaving Dokdo out of the final draft of the peace treaty was probably influenced by the fact that the Department could not get its view of the issue rectified with the British Commonwealth nations´ opinions, and most certainly because of a growing understanding of the intractability of the situation in regards to Korea and Japan. The Americans might have intentionally

left Dokdo´s territorial status obscure, hoping that the Koreans and Japanese could later settle the issue on bilateral terms,

thereby leaving the U.S. out of any potential dispute.

However, by not accepting the British proposal, and by shying away from defining Dokdo´s ownership, the Americans helped

create further discord in the relations between Korea and Japan for decades to come.

6/20/51: In a letter to the Korean Prime Minister Chang Myun, Deputy Army Commander Lieutenant General John B. Coulter

requested the use of "the Liancourt Rocks Bombing Range" on behalf of the U.S. Air Force. The letter promises that the

military authorities will provide a "15 days advance notice and to clear the area of any personnel or boats." On July 1st, the

Korean Prime Minister´s office approved the request, after disclosing it to the ROK Ministries of Defense and Home Affairs.

In January 1953, the Counselor of the U.S. Embassy in Korea, E. Allan Lightner Jr, was surprised when he

found this letter in the embassy´s files; especially after just learning that the State Department had supposedly revealed an

understanding of Japan´s sovereignty to Dokdo in August 1951. He noted in a letter to Major General Thomas W. Herren, that

"we in the Embassy were unaware of the fact that our military authorities had ever requested and obtained authorization from the

Koreans for the use of this island as a bombing range." View document

7/6/51: SCAP reasserts Dokdo´s status as a bombing range in SCAP Instruction #2160. This new order for the

Japanese government provided for warnings to be given to essentially the same populations on the Japanese west coast as had the earlier

SCAPIN, #1778. There is no provision in this instruction for warnings to be given to Korean populations.

It is possible that although Koreans were not mentioned in this SCAPIN, the assurances given to the Korean

government in General Coulter´s letter just weeks before seemingly provided the same warnings to Koreans. However, a bombing

incident that took place a year later in September 1952 seemes to bring General Coulter´s assurances into question. With the

issuance of this SCAP instruction to the Japanese following so closely after General Coulter´s letter to the Koreans, it seems the

U.S military, by appealing to both countries, was hedging its bets as to which country would have eventual control over Dokdo..

John Foster Dulles, Consultant to the U.S. Secretary of State (1951-1952) and later

Secretary of State (1953-1959).

|

7/9/51: Consultant to the Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, and special assistant to the Director of the Office of

Northeast Asian Affairs, Robert A. Fearey, meet with ROK Ambassador to the U.S., Yang Yu-chan. Dulles hands Yang the latest draft

of the peace treaty. After reviewing it, the Korean government noticed that the draft did not include certain Korean demands (such

as the preservation of the ´MacArthur Line´, war reparations from Japan, and Korean sovereignty over Tshushima). In

addition, the draft failed to include Dokdo and "Parangdo" in the definition of Korean territory. On July 17, the ROK

Foreign Minister, Pyun Yung-tai, withdrew the Korean demand for Tsushima.

7/13/51: A State Department geographer at the Office of Intelligence and Research, S.W. Boggs, replies to a inquiry from

Robert A. Fearey about territories that might be in contention between Japan and other countries after the signing of the peace treaty.

In regards to the islands in the East Sea/Sea of Japan, Boggs suggests that "Liancourt Rocks"(Dokdo) could be included in

the peace treaty, and that it might be "advisable to name the territories specifically in the draft treaty, in some such form as

the following (Article 2): (a) Japan, recognizing the independence of Korea, renounces all right, title and claim to Korea, including the

islands of Quelpart, Port Hamilton, Dagelet, and Liancourt Rocks". A few days later on July 16, Boggs writes to Fearey on

the same subject, stating that "[i]t should be noted that while there is a Korean name for Dagelet, none exists for the Liancourt

Rocks and they are not shown in maps made in Korea".

This correspondence shows evidence that the U.S. State Department was looking into (and was aware of)

potential future disputes arising from the wording of the then current draft of the peace treaty. More interestingly, it shows

just how influential the Japanese Foreign Ministry´s 1947 monograph "Minor Islands in the Sea of Japan" was to American

planners, for the very wording of S.W. Boggs´ July 16 letter to Fearey matches almost verbatim the wording of the Japanese

monograph.

7/19/51: Ambassador Yang again meets with John Foster Dulles and asks that the treaty be written to include Dokdo and

"Parangdo", asserting that both islands were Korean territory before the Japanese Annexation of Korea. Dulles tells Yang

that if his assertion is true, it would be no problem to include these islands in the treaty´s definition of Korea.

8/7/51: The State Department cables the American Ambassador to Korea, John Muccio, to inform him that the Department could

not locate Dokdo or "Parangdo" on any maps.

8/8/51: The U.S. Embassy in Korea replies to the State Department with the exact location of Dokdo (37 Degrees 15 Minutes

North, 131 Degrees 53 Minutes East), and includes in the cable a request from the ROK Foreign Minister to withdraw the Korean demand for

the ficticious "Parangdo".

The Korean government evidently withdrew its demand for "Parangdo" after realizing, at long last,

that the island did not exist(!) The "Parangdo" fiasco is an example of how ineffectively ROK President Syngman Rhee (Yi

Seung-man) presented his country´s demands in the negotiations for the peace treaty. The Rhee administration´s

unrealistic demands for Tsushima and "Parangdo" and its failure to prepare a well-documented study on the Korean case for

sovereignty over Dokdo (one sufficient to counter the claims in the Japanese Foreign Ministry´s 1947 monograph) had most likely

influenced the American decision to not include Dokdo in the definition of Korea in Article 2(a) of the peace treaty.

As Assistant Secretary of State in 1951, Dean Rusk wrote the memorandum of August 10,

1951 to the Korean Ambassador in Washington. Rusk later became Secretary of State from 1961-1969.

|

8/10/51: In response to their request for inclusion of Dokdo in the definition of Korea, Assistant Secretary of State Dean

Rusk sends a memorandum to the Korean government which states that the United States would not recognize the Korean ownership of Dokdo in

the peace treaty. It is interesting to note that the wording of Rusk´s explanation in this memo matches almost

exactly the wording of the Japanese Foreign Ministry´s 1947 monograph, "Minor Islands in the Sea of Japan":

As regards the island of Tokdo...this normally uninhabited rock formation was according to our information never treated as part

of Korea and, since about 1905, has been under the jurisdiction of the Oki islands Branch Office of Shimane Prefecture of Japan.

The island does not appear to ever have been claimed by Korea.

This statement again reiterates the failure of the ROK Government to provide a well-researched and complete

history of Korea´s ownership of Dokdo to the U.S. State Department during these negotiations. It is also a testament to the

influence that the Japanese treatise, "Minor Islands in the Sea of Japan" had on American planners. Although the now

infamous August 10, 1951 memorandum may be seen by some as the U.S. recognition of Japan´s claim to Dokdo, the final draft of the

peace treaty still did not reflect any U.S. position regarding Dokdo, as the islets were not mentioned at all in the treaty. In

fact, evidence suggests that the Americans never informed the Japanese Government of the existence of this memorandum and the position

stated in it. The reasoning for all of this has never been explained. It seems that the Americans were attempting to

(quickly) remove themselves from the territorial dispute over Dokdo by stopping the Korean demand dead in its tracks via the August 10

statement, but at the same time not telling the Japanese about it, and by avoiding mention of the islets in the final draft of the peace

treaty. Therefore, the real purpose of the U.S. State Department´s August 10, 1951 memorandum is open to interpretation.

Was the memorandum to serve more of an instrumental purpose in helping the U.S. get out of the dispute, or was it really a

straightforward policy decision (and if it was, why weren't the Japanese told about it)? Later statements from American officials

seem to support both interpretations, with the Americans tending to increasingly distance themselves from support for

Japan´s claim as the signing of the 1954 US-ROK Security Treaty came closer.

9/8/51: The San Francisco Peace Treaty between the former Allied Powers and Japan is signed by forty-eight nations.

The treaty´s article concerning Korean territory states: "Japan renounces all rights, titles and claims to Korea (including

Quelpart, Port Hamilton and Dagelet)", with no mention of Dokdo. Probably because many of the demands that his government had

made during the negotiations were not adopted in the treaty, Syngman Rhee did not send a representative to observe the proceedings.

The treaty would not be ratified by the United States Senate until April 1952.

It is important to note that Korea was not a signatory to the peace treaty, due to British concerns about

the Soviet Union´s non-recognition of the Republic of Korea (the Soviets eventually declined to sign the treaty), and to the poor

relations between the governments of Britain (under Prime Minister Clement Atlee) and the ROK (under Syngman Rhee). There were

also other reasons Korea was not a signatory: In the July 9 meeting during the negotiations, Secretary of State Dulles had told

Ambassador Yang that only those nations that were at war with Japan and had signed the UN Declaration of January 1942 would be able to

sign the peace treaty. In addition, Syngman Rhee´s Korean Provisional Government had never been formally recognized by the

Allied Powers during the war. In the end, it is important to note that the peace treaty can be viewed as a document that was a

product of the then emerging Cold War. This treaty, which was meant to settle the Pacific War with Japan and end the American

occupation, had instead become a treaty to tie Japan to the U.S. sphere of influence and control in order to counteract the Soviet Union

and Communist China. The Americans also wanted to maintain relations with the ROK. This need by the U.S., and the Korean

Government´s failure during the negotiations, are the very likely reasons why the treaty avoided mention of Dokdo.

Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Korea (1951-

1953), Pyun Yung-tai.

He is shown here appearing on a US television-interview program in December 1952.

|

10/3/51: The U.S. Embassy in Korea cables a copy of a letter to the State Department from ROK Foreign Minister, Pyun Yung

-tai, concerning the Korean claim to Dokdo. In the letter, Pyun based Korea´s claim largely on the basis of SCAPIN #677 of

January 29, 1946. He also stated that Korea has "substantial documented evidence" of its claim. In the memo that

accompanied Pyun´s letter, the Embassy told the Department that they believed that the Koreans "did not possess a

compilation of such ´evidence´ at this time" and that "it appears doubtful that such information will be

forthcoming".

The Embassy´s open disregard for the Korean Government´s claims are quite

evident in this letter, as is the Korean Government´s failure to secure and produce the existing evidence that could properly

exhibit Korea´s claim to Dokdo.

1952

5/4/52: The U.S. Fifth Air Force replies to a request that the ROK Government sent through its air force liason for

information on Dokdo´s status as a bombing range. The request was sent on April 25, at the behest of residents of Ullung

Island, who were concerned about the safety of fishing at the islets in the wake of the bombing incident that had taken place almost four

years previously on June 8, 1948. The reply from Fifth Air Force Headquarters, essentially stated that there had been no

prohibition on fishing around Dokdo, and that the island was not a Far East Air Force bombing range.

This reply from the Fifth Air Force is at odds with the fact that the U.S. military had requested and

received permission from the Korean Government to use Dokdo as a bombing range in June 1951. Additionally, there is no known

evidence to prove that either the Korean Government or the U.S. military had rescinded the use of the islets as a bombing range up to May

1952.

7/26/52: The "United States-Japan Joint Committee", comprised of U.S. and Japanese officials responsible for

implementing Japanese-American security arrangements, selects Dokdo as a "military facility" for use by American forces in Japan.

This was done in accordance with the "Administrative Agreement under Article III of the Security Treaty between the United

States of America and Japan". The Japanese Foreign Ministry also issues Resolution Number 34, which designated Dokdo as a

bombing range. According to a dispatch from the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, the area around Dokdo was declared a danger area and posted

out-of-bounds on a 24-hour, 7-day a week basis, with this information then disseminated throughout the Far East Command and to its

subordinate commands. There are no records or evidence to suggest that Korean military or civillian authorities were made aware of

this danger area around Dokdo.

Now that the occupation of Japan was over, it seems the U.S. military sought the Japanese out to take

governmental action (like SCAP had done during the occupation) to make Dokdo an ´official´ bombing range for American and

United Nations forces during the Korean War. Again, it is fairly evident from the available documentation that neither the Korean

government nor the American Embassy in Korea were made aware of the Joint Committee´s decision at the time. It seems that

American decision-makers were trying to get what they wanted (a bombing range) from the Japanese, and did not want to rattle the Koreans

over it.

9/15/52: The leader of an exploration group at Dokdo, Hong Chong-in, and his crew see an "unmistakably

American" mono-propellor aircraft make a circuit around Dokdo and drop four bombs on the islets, which sends the party scurrying

for shelter but causes no injuries. Five days later, Mr. Hong cables the ROK Minister of Commerce and Industry and the Naval Chief

of Staff, from whom he had received permission to travel to Dokdo by boat, after the request was given the go-ahead by the United Nations

Naval Commander in Pusan on September 7. In the cable, he demands that the naval leaders "establish an effective liasion

with the Air Force authorities" regarding this safety issue.

It is clear in this incident, which took place less than two months after the announcement of the Japanese

Foreign Ministry´s resolution Number 34, that the United Nations Naval Commander in Pusan (an American), was not aware that the

island was a designated bombing range and had been placed off-limits. Such an occurrence would seem to prove that authorities in Korea

(whether Korean or American) were neither involved in, nor even informed of the decision made by the Joint Committee.

Although not causing any deaths or injuries like the 1948 bombing had, this 1952 bombing incident at Dokdo had caused great concern in

Korea over the territorial sovereignty of the island, and really established the Dokdo issue in the Korean public consciousness.

The Korean press gave it a good deal of coverage, and the incident set events in motion that would result in the end of the

island´s use as a bombing range six months later.

10/3/52: Writing on behalf of Ambassador to Japan, Robert Murphy, the First Secretary of the American Embassy in Tokyo,

John M. Steeves, writes Despatch No. 659 entitled, "Koreans on Liancourt Rocks", concerning the September 15 bombing incident,

which he calls "a minor incident which may achieve larger proportions in the near future". In it he states that

while the reassertion of the danger area around Dokdo should "suffice to prevent the complicity of any American or UN Commanders

in any further expeditions to the rocks which might result in injury or death to Koreans", the Korean government would not be

able to dissuade its fishermen from sailing there. He further suggests that, as such, any other incidents caused by the U.S. might

"bring the Korean efforts to recapture these islands into more prominent play, and may involve the United States unhappily in the

implications of that effort."

This informational despatch explains some of the concerns that American Embassy staff in Tokyo had

regarding the U.S. military´s continued use of Dokdo as a bombing range. What is also interesting about this letter is that

Steeves provides a short history on the sovereignty of Dokdo as follows:

The history of these rocks has been reviewed more than once by the Department, and does not need extensive recounting here.

The rocks, which are fertile seal breeding grounds, were at one time part of the Kingdom of Korea. They were, of

course, annexed together with the remaining territory of Korea when Japan extended its Empire over the former Korean State.

The statement, which says that the State Department has reviewed the history of Dokdo and that the islets were once a part of Korea, is a

direct contradiction to the statement made in Dean Rusk´s August 10 memorandum to the Korean Ambassador in Washington. The

history of Dokdo related in this October 3 despatch really begs the question(s): From where did the American Embassy in Tokyo get

their information, and what can account for the differences in the statements made in this despatch and those made in the August 10

memorandum? The implication here is that if the State Department had reviewed the history of Dokdo more than once, and that the

conclusion of those reviews was that the islets had once been a part of the Kingdom of Korea, then the Americans had an understanding of

Dokdo that was quite divergent from their policy of not recognizing the Korean claim.

E. Allan Lightner, Jr. Lightner was the Charge d´Affaires (ad interim)

of the American Embassy in Korea in 1952-1953.

|

10/16/52: The ad interim Charge d´Affaires of the American Embassy in Korea, E. Allan Lightner, Jr., writes a letter

entitled, "Use of Disputed Territory (Tokto Island) as a Live Bombing Area",to the American Ambassador to Japan, Robert Murphy,

and sends copies of this letter to the Director of Northeast Asian Affairs, Kenneth T. Young, and General Herren, Commanding General of

the Korean Communications Zone. In the letter, Lightner recognizes that "the decision to use this isolated pile of rocks as a

bombing target was made in Tokyo" and that there are "potentially explosive political implications".

Therefore, he suggests that the military might want to "lay off this particular island".

Like the October 3 letter from the Embassy in Tokyo, this letter shows just how disconcerting the bombing

incident had become for the American Embassy staffs. Their urgency in retracting the U.S. from any involvement in Dokdo, and the

potential consequences, is palpable here. It is also important to note that the governments of Japan and Korea were, at the time,

in the preliminary stages of talks over the resumption of diplomatic relations, and that the Americans were afraid that this incident

might shatter the already difficult Korean-Japanese relationship.

September 1952: In an undated letter, the Commanding General of the Far East Command, General Mark W. Clark, sends a reply

to E. Allan Lightner, Jr´s letter of October 16. In it, the General relates that he has initiated an investigation of the

bombing incident and will provide information that is suitable to be given to the ROK Foreign Ministry.

This letter marks the beginning of the American effort at damage control over this incident, which had

resulted in a great deal of press coverage in Korea at the time. This letter also raises the question: If the military

thought that Dokdo was a ´facility of the Japanese Government´ (as agreed to by the United States-Japan Joint Committee on

July 26 in Tokyo), then why would the commander of the Far East Command feel it necessary to provide information on this incident to the

Korean Government? It seems that the Americans did not want the Koreans to know about the decision that was made by the Joint

Committee in Japan. Interestingly, a note was attached to the front of this letter to Lightner. The hand-written note was by the

Director of the Political Section, Mr. R.H. Bushner, who wrote:

"Let´s not get in an uproar over this -B"

Bushner was either alluding to the potential political problems involved, or perhaps he was suggesting to the diplomats that they avoid

blaming the military too harshly.

10/20/52: The Air Attache of the American Embassy in Taegu sends a report to R.H. Bushner of the Political Section.

In this report, the Air Attache states that he had just visited 5th Air Force headquarters, and although they would not admit that it was

a 5th Air Force plane that bombed Dokdo on September 15, they did make assurances that orders had been given to the effect that

"further bombing of the island would not be conducted."

This is the first known statement on

the discontinuance of Dokdo´s use as a bombing range.

11/10/52: The ROK Ministry of Foreign Affairs sends a formal note verbale to the American Embassy in Pusan. In this

Note, the Ministry asks for "any detailed information" that the Embassy might have on the September 15 bombing incident at

Dokdo, an island that they state "is a part of the territory of the Republic of Korea." They further request that

the Embassy "take necessary steps in order to prevent recurrence of such incident."

Kenneth T. Young, Jr. was the Director of Northeast Asian Affairs in 1951. He

is pictured here as U.S. Ambassador to Thailand in 1964 (right).

|

11/14/52: The State Department´s Director of Northeast Asian Affairs, Kenneth T. Young, Jr., writes a letter to

Charge d'Affaires, E. Allan Lightner Jr., of the American Embassy in Korea. In this letter, Young tells Lightner that he has read

Tokyo´s despatch of October 3, and Lightner´s letter of October 16. Referring to the August 10 memorandum, he tells

Lightner that "[i]t appears that the Department has taken the position that these rocks belong to Japan and has so informed the

Korean Ambassador in Washington". Young explains that during the peace treaty negotiations, the Secretary of State

told the Korean Ambassador that the "United States could not concur" to the Korean request to include Dokdo in Article 2

(a) of the treaty, since "according to [the Secretary of State´s] information" the islets were never a part of

Korea, or claimed by Korea, but were under the jurisdiction of Shimane Prefecture, Japan. Young then goes on to say that it is

"therefore justified" that the Joint Committee designated Dokdo as a facility of the Japanese Government. He also

plays down the Korean claim based on SCAPIN 677 of January 1946, stating that this was an instruction "which suspended

Japanese administration of various island areas, including Takeshima (Liancourt Rocks), [but] did not preclude Japan from exercising

sovereignty over this area permanently." To further back up his statements, Young adds that SCAPIN 1778 afforded

notification of the use of the bombing range to only Japanese residents of Oki Island and Western Honshu.

This letter is the strongest case yet made for the view that the August 10 memorandum was a policy

statement of the State Department. However, what cannot be made clear is why, at the very time that this letter was written, the

Americans were reacting to Korean Government concerns and had ceased the bombing of Dokdo because of those concerns. If the U.S.

policy towards Dokdo was that the islets were not Korean territory (according to the August 10 memorandum and the peace treaty) and were

considered a facility of the Japanese Government by the Joint Committee, then why didn´t the Americans stand by their policy and

inform (or re-inform) the Koreans of U.S. decisions? It seems the Americans were less inclined to support the Japanese claim to

sovereignty to Dokdo if it meant that doing so would cause problems in the Korean-Japanese (or Korean-U.S.) relationship.

Essentially, the American policy was that the U.S. would maintain their ostensible (and rather weak) view of Japanese sovereignty over

Dokdo in order to use the area as bombing range, but only until the Koreans found out about it, and then quickly pull out of the dispute

by discontinuing the bombing of the islets. As we will see later, the Japanese were not very happy about the American

retraction from the Joint Committee´s decision.

Another observation that can be made from this letter is that Young did not counter the assertion made in the October 3 despatch that

stated that the Department reviewed the issue many times before and had concluded that Dokdo was once a part of the Kingdom of Korea.

He only repeated statements made by Dean Rusk on August 10. This again begs the question: Why there were two

radically different understandings of the sovereignty of Dokdo in State Department documents? One possible reason is that the

State Department eventually came to know of Korea´s historical connection to Dokdo, but the Department made the deliberate choice

to view the Japanese claim more favorably, placing more credence in Imperial Japan´s ´formal incorporation´ of the

islets in 1905. Other, possibly more important factors, may have been the warmer relations the Americans had with the Japanese

vis-a-vis the Koreans in this period, the efforts made by the Japanese Foreign Ministry combined with the failures of the ROK Foreign

Ministry during the peace treaty negotiations, and of course, the military´s need for a bombing range in the East Sea/Sea of Japan.

Any of these might have influenced the Americans to give a more favorable view to the Japanese claim at this time. As was

stated earlier, the Americans were to pull back from supporting Japan´s claim by 1954, probably because it no longer served

American interests.

11/26/52: The Office of the Secretary of State sends a telegram to the American Embassy in Korea. The Department

writes that they agree with Lightner´s assertion that the U.S. "should not become involved in any territorial dispute

arising from [a] Korean claim to Dok-do Island." In this telegram, the Department gives the Embassy instructions on the

wording of their response to the ROK Foreign Ministry´s letter of November 10. The letter goes on to tell the Embassy to

include the following statement in the final paragraph: "The U.S. Government´s understanding of [the] territorial status

[of] this island was stated in Assistant Secretary Dean Rusk´s Note to Ambassador Yang dated August 10, 1951." The

Department also tells Lightner the reasoning for this:

"Such a statement would merely reiterate previous U.S. views, would withdraw U.S. from [the] dispute, and might have

[the] desirable result in discouraging [the] ROK from intruding [this] gratuitous issue in [the] already difficult Jap[anese]-Korean

Negotiations".

This telegram highlights the pragmatic funtion that the August 10 memorandum served in American dealings with

the Koreans on the Dokdo issue. Here again, it is clear that the Americans were trying to stop the Korean demand for Dokdo dead in

its tracks, fearing the Koreans would introduce the Dokdo issue in the on-going negotiations on the normalization of relations between

Korea and Japan.

11/27/52: Writing on behalf of General Clark, Lt. General Doyle O. Hickey of the Headquarters of the Far East Command

(FEC) writes to E. Allan Lightner of the American Embassy in Korea with information on the status of the investigation of the September

15 bombing incident. Hickey states that as more than two months have passed, it is impossible to determine if the incident was

caused by a plane under their command, and that there are no records of any air units having requested the use of Dokdo as a bombing

target at that time. The letter adds that "our staff is making preparations to dispense with the use of Liancourt Rocks as

a bombing range and upon suspension, the Republic of Korea as well as other interested agencies will be notified."

12/4/52: The Charge d'Affaires of the American Embassy in Korea, E. Allan Lightner, replies to the letter of November 14

from Kenneth T. Young, Director of the Office of Northeast Asian Affairs of the State Department. Lightner writes that the

American Embassy staff in Korea were not aware of the August 10 memorandum. He also states that the Embassy staff in Korea knew

that Article 2(a) of the peace treaty did not address Dokdo. However, Lightner goes on to say that they "had no inkling

that [the] decision constituted a rejection of the Korean claim. Well, now we know and we are glad to have the information as we

have been operating on the basis of a wrong assumption for a long time."

This letter shows that not only were the Japanese Government not informed of the existence of the August 10

memorandum, neither was the American Embassy in Korea. If the August 10 memorandum were truly a policy statement, it seems quite

strange that the State Department did not want to share this policy with practically any of the interested parties other than the ROK

Foreign Ministry. Again, Dean Rusk´s August 10 statement seems to have been made only to get the Koreans to back off from

their claim, thereby keeping the issue out of Korean-Japanese relations.

1953

1/5/53: Counselor of American Embassy in Tokyo, William T. Turner, writes to E. Allan Lightner of the American Embassy in

Korea. Turner relates that effective December 18, 1952, the use of Dokdo as a bombing range had been discontinued. He

states that a new bombing range has been substituted for Dokdo by the Commander in Chief of the Far East (CINCFE). The new

coordinates are given as 37°15´ North, 131°52´ East (empty sea space directy East of Ullungdo). Turner asks

Lightner to request General Herren to communicate this information to the Korean Government.

General Thomas W. Herren, Commanding General of the Korean Communications

Zone.

|

1/20/53: The Commanding General of the Korean Communications Zone, Major General Thomas W. Herren, informs the Korean

Government of the decision to discontinue the use of Dokdo as a bombing range, and of the new area that has been substituted for Dokdo.

3/3/53: The American Ambassador to Korea, Ellis O. Briggs, sends a telegram to the State Department about a statement made

on February 27 by the ROK Defense Minister. The Defense Minister was quoted in the Korean press as saying that the Commander of

the Far East Air Force (FEAF), General Otto Paul Weyland, sent the ROK Defense Ministry a letter promising that no further bombing of

Dokdo would take place; with the Minister implying that this letter was essentially a U.S. Government recognition of Korean sovereignty

over Dokdo. The Embassy reports that the Japanese have read this and consider the ROK Defense Minister´s statement very

significant, and that Japanese Foreign Ministry sources say that they will introduce this topic in the agenda during upcoming talks

between the Korean and Japanese Governments. The Embassy also relays to the Department their hope that "any future

communications to ROK Govt relating to Dokdo...would be transmitted through [the] Embassy so that there can be no possible misconception

as to [the] US position, which as we understand it is that this Island [is] not...subject [to] Korean jurisdiction." The

Embassy also tells that it fears that this new dispute will deteriorate the relations between Korea and Japan, and that they believe the

ROK Government has probably distorted the meaning of any such note from General Weyland to suit its own purposes.

The State Department would later look into the allegation that Weyland wrote such a letter and would

conclude (by March 12) that he did not do so, nor was any such letter sent to the ROK Defense Ministry. A notable fact here was

that it seems the Embassy in Tokyo was upset by the confusing way in which the U.S. Government was handling the Dokdo issue. On

the one hand, the Americans cut a (secret) deal with the Japanese for a bombing range at the islets and then, when the Koreans found out,

the Americans sent assurances to the ROK Government that they would immediately discontinue the bombing. The report on the alleged

"Weyland letter" only heightened their concern about this confusing policy.

The ROK Defense Ministry alleged that General Otto Paul Weyland sent their office a

letter that promised that Dokdo would no longer be used as a bombing range.

|

3/5/53: American Ambassador to Japan, Robert Murphy, cables the State Department with new information on the Japanese

reaction to the news that Dokdo would no longer be used as a bombing range. That day, the Japanese Foreign Office contacted the

Embassy to confirm Weyland´s reported statement on Dokdo and wanted to know "why [the] Japanese Government [was] not

formally notified through [the] joint committee if [the] Islands [were] no longer used as [a] military facility." They

also told the Embassy that the Governor of Shimane Prefecture was now in Tokyo looking for answers to this question, as fishermen from

his prefecture would have taken advantage of the rescission of the islets´ status as a bombing range. The Japanese Foreign

Office also related their belief that the U.S recognized Japanese sovereignty over Dokdo, and stated that they "might find it

necessary to ask that [the] United States clarify its views on the subject." Murphy also tells the Department that

FEAF Headquarters can find no record of any letter from Weyland to the ROK Government on the subject, and that they would consider

issuing a public denial of the letter. He also admits, that while the Japanese have now been informed orally, the Far East Command

(FEC) indeed did not notify the Japanese Government through the Joint Committee that the islets would no longer be used as a

military facility. Murphy ends the telegram by relating the following concern:

"Once Weyland denial and formal notification through [the] joint committee [is] obtained [the] Japanese presumably will use

these to back up [a] firm new assertion of sovereignty over [the] Islands, [and have] probably authorized dispatch [of] fishing and other

vessels to [the] Area. ROK reaction can be anticipated.".

Again, it is clear that the U.S. did not relate the opinion that was stated in the August 10, 1951 memorandum

to the Japanese Government, since the Japanese felt the need for a clarification of the American stance on the Dokdo issue. What

also can be seen here is the fact that the FEC did not even take the time to formally notify Japan of the rescission through the Joint

Committee. This is a good indicator that the Americans were keenly aware of the repercussions of the September 15, 1952 bombing,

and were trying to distance themselves as quickly as possible from any potential trouble resulting from the incident.

3/17/53: The American Ambassador to Japan, Robert Murphy, sends a telegram to the State Department to notify the Department

that the Japanese Government were notified orally (not formally) in a meeting of the Joint Committee that Dokdo would no longer be used

as a bombing range. He also states that the American Embassy told the Japanese in a similar fashion that there was no evidence of

General Weyland´s letter, and that there was no official American statement recognizing the Korean claim to Dokdo. Murphy

also felt confident that the Japanese were "satisfied with [the] oral statements" so far, and that no formal written

notification would be probably be necessary for either the denial of Weyland´s letter or for the discontinuance of Dokdo as a

military facility.

It seems the Americans were interested in making sure that they made no formal written statements on these

issues, which could be used as justifications by either the Koreans or the Japanese for their respective arguments for sovereignty over

Dokdo. The State Department seems to have issued a full retreat here.

7/14/53: The new American Ambassador to Japan, John M. Allison, cables the State Department notifying them of a new

incident that took place at Dokdo on July 12. Allison relates the particulars of the incident that he received from Japanese

sources. On the morning of July 12, a 450-ton Japanese MSB patrol vessel, the ´Hekura´ approached within close

proximity of the Dokdo islets and encountered Korean fishing vessels and police armed with automatic weapons. The Japanese

reported that 3 Koreans and their police chief came aboard the Hekura and told the Japanese that the islets were Korean territory and

that the Japanese vessel should proceed to Ullungdo and report to Korean authorities there. After the Koreans went ashore, the

evidently frightened crew of the Hekura proceeded to steer their ship out of the area by going around the islets before returning to

their base at ´Maizuru´, when "[s]uddenly [the] vessel was subjected to fire from shore by carbines and/or light

machine guns; of 40-odd shots, 2 hit [the Hekura]."

Allison goes on to say that the Japanese Foreign Office delivered two notes verbale to the Korean Mission in Tokyo on July 13; one

protesting the incident and demanding that the Koreans withdraw from Dokdo immediately, the other, a previously-prepared explanation to

the Koreans on Japan´s sovereignty to the islets. Allison also reports that the incident had become a major news story in

Japan, with the Jiji Shimpo suggesting that the Government of Japan should mobilize the Japanese ´Self-Defense

Forces´, while the Yomiuri quoted a source that said that the Government was going to request American assistance or submit

the case to the Hague Tribunal. Despite his observation that "Diet members of all parties [are] extremely sensitive to

´acts of aggression´ against Japan by Korea", Allison states that Foreign Office desk officers told him that the

Japanese Government is not contemplating any of the actions reported in the media, but that they were only studying the possibility of

taking the issue to the Hague.

Korean volunteer forces, led by Korean War hero Hong Soon-chil, had been stationed at Dokdo since April 20.

This endeavor was sponsored by the Rhee regime, who armed the volunteer guards with various automatic and crew-served weapons,

including mortars. The Japanese Government had already complained about this Korean deployment to Dokdo prior to the July 12

incident, asserting the supposed "solemn fact that Take-shima has always been a part of Japanese territory throughout its long

history." In their July 13 note verbale to the Korean Mission in Tokyo, the Japanese Government cited various

ancient precedents for Japanese sovereignty over Dokdo, including responses to assertions the Korean Mission made in notes verbale

to the Japanese on February 12, 1952 and June 26, 1953, that cited recent developments within the previous eight years. The

Japanese respond, stating that the limitations placed on Japan in SCAPINs 677 and 1033 were removed by a memorandum to the Japanese

Government on April 25, 1952 (three days before the San Francisco Peace Treaty went into effect). They also mention Article 2(a)

of the peace treaty, which did not mention Dokdo as a Korean territory, and include the exclusion of Dokdo from the designated manouver

grounds for U.S. forces in March, which they state was "doubtlessly...based upon the fact that the island is a part of the

Japanese territory." It is interesting to note that in their vigorous objection to the Korean claim to Dokdo, the Japanese did

not mention any clearly-worded American opinion on Dokdo, such as the one stated in the August 10, 1951 memorandum to the Korean

Ambassador to the U.S. Again, it is very clear that the Americans did not provide the Japanese with any such formal statement

regarding the U.S. view towards the sovereignty of Dokdo.

7/21/53: The American Embassy in Tokyo sends translations of the Japanese notes verbale to the American Embassy in

Korea. The Tokyo Embassy relates their belief that "there is every reason to believe that as in the past the Japanese

protests will be summarily rejected [by the Koreans]", and includes the following summary of comments that Korean Mission

Couselor Yu Tae-ha made on July 15 to an officer of the Japanese Foreign Office:

"[Yu] told the drafting officer that the incident was clearly the fault of the Japanese, that the Japanese historical

arguments was ´ridiculous´, and that the island was unquestionalby Korean territory; he believed that the ´fuss´

over the incident was largely the result of agitation by Diet members from Shimane Prefecture who are after [Japanese Foreign Minister]

OKAZAKI´s scalp, and indicated that the [Japanese] Foreign office protest, which was designed primarily to stave off Opposition

criticism at home, would not be taken very seriously by the Republic of Korea."

9/28/53: The American Ambassador in Seoul, Ellis O. Briggs, sends the State Department copies of "The Korean

Government´s Refutation of the Japanese Government´s Views Concerning Dokdo (´Takeshima´) Dated July 13,

1953" which the Korean Mission released in Tokyo on September 9. The Korean publication was a response to the Japanese note of July

13. The Embassy writes that the publication "may be of some use as a summary of the Korean evidence for their sovereignty

[over Dokdo]."

The Korean statement that was released on September 9 advanced ancient historical claims to Dokdo and

referred to SCAPIN 677 and General Weyland´s note to the ROK Government on February 27, 1953 to further explain the Korean claim.

The statement also asserted that the omission of Dokdo from Article 2(a) of the peace treaty does not affect Korea´s claim

to sovereignty. The Korean publication makes a rather interesting observation about Article 2(a):

"[T]he Japanese Government says that the article does not specify that Dokdo is a part of the Korean territory like Chejudo

(Quelpart), Kumundo (Port Hamilton) and Ulneungdo (Dagelet). However, the enumeration of these three islands is by no means

intended to exclude other hundreds of islands on the Korean coasts from Korea´s possession. If Japan´s interpretation

on this matter were followed, hundreds of islets off the western and southern coasts of Korea besides those three islands would not

belong to Korea, but to Japan. If Japan, with such arguments, really asserts that ´Takeshima constitutes a part of Japanese

territory´, is the Japanese Government going to claim territorial ownership over all the islands off the coasts of Korea except the

three islands of Cheju, Kumun and Ulneung?"

12/9/53: Secretary of State John Foster Dulles cables the American Embassy in Tokyo with views on how to handle the growing

Japanese concerns regarding Dokdo (See Document). He opens the telegram with the following paragraph:

"[The] Department [is] aware of peace treaty determinations and US administrative decisions which would lead [the] Japanese

[to] expect us to act in their [favor] in any dispute with [the] ROK over [the] sovereignty [of] Takeshima. However to [the]

best of our knowledge [a] formal statement [of the] US position to [the] ROK in [the] Rusk note [of] August 10, 1951 has not...been

communicated [to the] Japanese. [The] Department believes [that it] may be advisable or necessary at sometime [to] inform

[the] Japanese Government [regarding the] US position on Takeshima. [The] Difficulty [at] this point is [the] question of timing

as we do not...wish to add another issue to [the] already difficult ROK-Japan negotiations or involve ourselves further than necessary in

their controversies, especialy in light [of] many current issues [that are] pending with [the] ROK."

Dulles goes on to state that despite the U.S. view of the peace treaty and the actions of the Joint Committee, "it does

not...necessarily follow [that the] US [is] automatically responsible for settling or intervening in Japan´s international

disputes, territorial or otherwise, arising from the peace treaty. [The] US view re Takeshima [is] simply that of one of many

signatories to [the] treaty." He says that the U.S. is not obligated to "protect Japan" from Korean

"pretensions" to Dokdo, and that such an idea "cannot...be considered as [a] legitimate claim for US action under [the

U.S.-Japan] security treaty." Dulles then draws a parallel to the Soviet occupation of the Habomais (islands off the coast

of Hokkaido) which the U.S. publicly declared are Japanese territory. Here, this "far more serious threat to both [the]

U.S. and Japan" does not obligate the U.S. to take action against the Russians, and the Japanese themselves would not expect this

to be the American obligation under the security agreement. Dulles also shares his fear that the Japanese would learn that,

actually, "[The] security treaty represents no...legal commitment on [the] part [of the] US." He also notes that

"Japan should understand [that the] benefits [of the] security treaty should not...be dissipated on issues susceptible [to]

judicial settlement." Dulles then closes the message with the instruction that the U.S. should not get involved in the

dispute over Dokdo, and that "no action on our part [is] required", but if the issue is brought up to the U.S. again, the

American line should be that the Koreans and the Japanese should take the issue before the ICJ [International Court of Justice].

The statements made in this telegram show just how weak U.S. support for the Japanese claim to Dokdo really

was. The Americans were just as worried about Japanese "pretensions" to Dokdo as they were about Korean ones. It

is clear that the State Department was not so willing to explicitly support the Japanese claim at any time, but particularly in

late 1953 when doing so could get in the way of the "many current issues" underway between the U.S. and the ROK, namely

the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty that was to be signed the following year. While just short of a complete abandonment of the

Japanese claim, this telegram definitely shows the Americans to be washing their hands of the Dokdo issue.

1954

6/5/54: The American Embassy in Korea cables the State Department to report on an incident that took place at Dokdo on May

23 and 24. According to Korean news accounts, an armed patrol boat flying the Japanese flag sailed past the islets. The

next day, around 200 Korean fishermen witnessed an aircraft machine-gun strafe Dokdo and fly away in the direction of Shimonoseki.

The aircraft was "determined to be Japanese after intensive investigation by ROK authorities", and at least one witness

was reported to have seen "Japanese markings on [the] plane."

6/26/54: John M. Allison cables the American Embassy in Korea to report on a United Press story from June 17 that quoted an

announcement by the ROK Home Minister that a ROK Coast Guard unit is to be stationed at Dokdo and permanent installations are to be

built. The Ambassador relates that the Japanese Foreign Office approached the Embassy asking if the story was true, and that the

Japanese felt that "permanent ROK occupation would ´Alter [the] whole situation´."

6/29/54: The American Ambassador in Korea, Ellis O. Briggs, asks the U.S. Naval Attache in Pusan for "any

information you can obtain discreetly" to confirm the recent press stories about Korean Coast Guard deployment and permanent

installations at Dokdo.

8/11/54: The Naval Attache in Pusan reports to the Embassy in Seoul:

"Naval Advisory Group advises ROK CNO [Chief of Naval Operations] visit 8 July Ullungdo Island (Utsuryoto) 37 degrees 27

minutes north 130 degrees 50 minutes east. Second time underway ROK ship as CNO. Stated purpose in connection hydro-electric

generator station there. Believe could be connection Tokto Island trouble. Will advise."

8/20/54: The ROK Foreign Office delivers a note to the American Embassy in Seoul stating that the ROK has established and

commenced the lighting of a lighthouse on the northeast point of Dokdo, "its territory in the eastern sea of Korea", on

August 10. The Ministry asks that this information be transmitted to U.S. Government authorities so that the new lighthouse may be

noted on American charts.

It is interesting to note that the lighthouse became operable on the third anniversary of the issuance of

Assistant Secretary of State Dean Rusk´s memorandum to the Korean Ambassador in Washington on August 10, 1951.

Perhaps the Koreans had deliberately chosen this date as a sort of message to the Americans?

8/24/54: The American Ambassador in Tokyo, John M. Allison, cables the State Department on some issues raised by the

Korean´s establishment of a lighthouse on Dokdo. Allison relates to the Department that the Japanese are "apparently

not...yet aware" that the Koreans have built a lighthouse on Dokdo, but that when they do find out, the Japanese Government,

media, and citizenry "would regard [the] establishment [of] permanent ROK installations [on] Takeshima as [an] extremely serious

matter."

Allison perceives two major problems for the U.S:

"(a) What to say to the Japanese when they ´bring the matter to our attention´; (b) what action if any we take on

[the] ROK Foreign Office note."

In regards to (a), he states that the Japanese Foreign Office has approached the Embassy on a number of occasions asking for information

on ROK activities at Dokdo, and that they at the Embassy have always stated that the Embassy "´has no information´ on

the matter", despite the fact that they indeed did know about it. Allison believes that it is not wise to

"affect ignorance any further [as the] Japanese will hardly believe [that the] lighthouse could have been built without US

knowledge" and that keeping up this stance will surely make the Japanese think that the U.S. was somehow involved. He

believes that the only course is to tell the Japanese that the U.S. had indeed been informed of the lighthouse, but not that the U.S. had

any prior knowledge of it.

In regards to (b), Allison thinks that the U.S. should re-inform the Koreans of "our interpretation of [the] JPT [Japanese Peace

Treaty]...or else ignore [the] note altogether and assume [the] risk that [the] ROKs will interpret silence as consent."

He believes that the Koreans should at least be told that the U.S. does not recognize or acquiesce to the ROK claim to Dokdo.

Allison goes on to wonder whether the "time has not...come to make US position on Takeshima clear." While

acknowleging that it would not be wise to get involved in the dispute while the islets were an "unoccupied no-man´s

land", he states that he believes that the "ROK fait accompli changes [the] picture" and that U.S. silence

on the issue may make the Koreans think that the U.S. is "acquiescing in [the] ROKs forceful assumption of sovereignty over [the]

island--which as both [the] ROK and Japan know (even though [the] latter [were] never officially informed) constitutes [a] violation [of

the] terms [of the] JPT as interpreted by [the] US." Despite this, Allison recognizes that this probably is not an option

that the State Department would consider (due to the ongoing Yang-Iguchi talks), and suggests that alternatively, the Japanese could be

told to simply add their concern about Dokdo to other concerns at the next ROK-Japan conference. He also thinks that the U.S.

could suggest to the Japanese to take the issue to the ICJ.

In the end, the Ambassador´s suggestion that the U.S. formally inform both parties of the

official American view never materialized. The ROK´s stationing of the Coast Guards at Dokdo did not force the

U.S. hand in any backing of the Japanese claim. As we will see, the Americans settled instead on suggesting to the Japanese that

they take the territorial dispute to the ICJ; a suggestion that they later downplayed as hurtful to Korean-Japanese relations.

8/24/54: On the same day as the message above, John Allison cables the State Department with news that the Japanese Foreign

office has made an inquiry at the Embassy about a press story that already came out about the lighthouse. He states that the

Embassy did receive notice of the lighthouse from the ROK, and that the Embassy was, at this time, "seeking confirmation and

further details." Allison also reports that the Japanese told him that the day before, on August 23, a Japanese MSA patrol boat

was "subjected to heavy fire from Takeshima shore." The Japanese told him that they would file a protest, but that they

would keep the protest confidential, unless the Koreans announced it.

8/25/54: The American Embassy in Korea cables the State Department about the Embassy´s views regarding the

ramifications of the recent Korean actions at Dokdo. The Embassy states that a public announcement of the official U.S. position

on Dokdo would be unwise at a time when the Yang-Iguchi talks are underway and a possible reopening of the ROK-Japan negotiations could

take place. Like Allison, the Korean Embassy also believes that an oral statement be made to the Koreans to the effect that the

U.S. "deplore[s] their taking unilateral action while status [of the] island [is] under dispute" so that the Koreans will

not "interpret silence as consent." They also believe that adding this issue to the negotiation agenda between

Korea and Japan would reduce the chances that the talks succeed, but that it is probably unavoidable. Again, they suggest that the

U.S. make oral statements to both sides that the issue "be discussed in bilateral talks and that in [the] meantime no action of

[a] provocative nature be taken by either side", although the Embassy admits that bilateral talks are unlikely to resolve the

issue. They also suggest caution on this issue as the Korean Government has not been very successful in its dealings with

Washington:

"In considering possible courses of action on this question we should recognize that Pres RHEE and ROK Govt are not...in [a]

receptive mood for further public setbacks. [The] General impression in Korea [is] of relative lack of concrete success by RHEE in

his U.S. visit coupled with [the] effects of recent redeployment announcements [and] are not [a] happy framework in which to take up

[the] issue of Tokto. ...it is important therefore that we seek to avoid publicity on [this] question and merely set record

straight in factual terms as regards U.S. Govt position in manner suggested above."

8/26/54: The State Department cables the Embassies in Seoul and Tokyo with instructions on how to handle the current

situation regarding Dokdo. The Department tells the Embassies that a statement of the official U.S. position is

"innapropriate at this time", and that the Department is planning to "inform [the] ROK that [the] U.S. cannot

consider ROK action as affecting US position [on the] issue [of] sovereignty over Liancourt, which [is] now [the] subject of

controversy between ROK and Japan, but that [the] US will inform appropriate US authorities [that the] lighthouse [has been]

constructed on [the] island by [the] ROK." The Department also instructs the Embassies to notify the Governments of Korea

and Japan that the U.S. will issue a formal reply to the ROK regarding their announcement of the lighthouse, and tells the Embassy in

Seoul to tell the ROK Foreign Office that the "US deplores [the] reported ROK use of force [in] connection [with]

Liancourt..."

9/27/54: The American Embassy in Tokyo informs the State Department about a visit from an official of the Japanese Foreign

Office. The Embassy reports that on this day, the Japanese official came by to inquire about possible reactions to a Japanese

proposal to submit the Dokdo dispute to the ICJ. The Embassy notes that the official "wondered also if [the] US

couldn´t try to ´persuade´ [the] ROK to accept [the] proposal." The Embassy relates the fact that the

Japanese Foreign Office has issued the ICJ proposal to all of the foreign missions in Tokyo in an effort to appeal to world opinion,

while they do not place much hope in the ROK accepting the idea. The Japanese also report that they have entertained the idea of

submitting their problem to the United Nations (Security Council), although it is not yet being seriously considered.

9/29/54: The State Department cables the American Embassies in Taipei and Seoul with its ideas on persuading the Koreans to

negotiate with the Japanese on the Dokdo issue. He mentions ROK president Rhee´ recent visit to Washington, and that

"US efforts to modify RHEE´s general attitude toward Japan during his Washington visit were unavailing." This

being the case, the Department states that Taiwan may play a role:

"In view [of] RHEE´s emotional conviction [that the] US [is] discriminating against Korea in favor [of] Japan and [the]

generally unfavorable Korean attitude toward US-Japan cooperation, [the] Department believes [that a] US attempt [to] exert influence on

Korea would do more harm than good. [The] Department continues [to] consider Chinese intercession most effective as China [is] in

[the] position of [an] objective third party which while sharing Korean feeling of greivious injury at [the] hands of [the] former enemy

has nevertheless adopted Governmental policy of reason and realism."

11/16/54: The First and Third Secretaries, Mr. Tanaka and Mr. Matsuoka of the Japanese Embassy in Washington D.C. meet with

State Department Officials at the U.S. State Department on the evening of November 16 to discuss the Japanese proposal to refer the Dokdo

issue to the Security Council. Mr. Tanaka begins by explaining that the Government of Japan is considering taking their problem

with the Koreans before the United Nations Security Council in order to gain a recommendation from the Council that the issue be taken to

the ICJ. Tanaka states that Japan felt this necessary as the Koreans refused the September 25 Japanese suggestion of ICJ

arbitration in a note verbale on October 28. He says that his government feels the need to take this further step due to

domestic pressures in Japan and that a recommendation by the Security Council would garner world opinion in Japan´s favor, by

showing that Japan was willing to submit to the third-party arbitration and the ROK was not. Mr. Tanaka then asks "whether

the United States would vote in the SC in favor of referral of the issue to the ICJ."

Eric Stein of the State Department replies that it would be possible for Japan to take the issue before the Security Council under

Article 35, paragraph 2 of the UN Charter, citing the Corfu Channel case between Britain and Albania, in which Albania had done so, but