addicts haunts

Tegucigalpa Streets

By Ronald J. Morgan

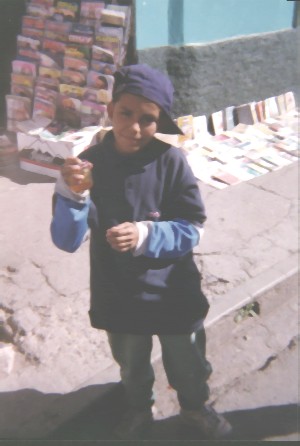

For three years the life of Charlie Reyes was

incredibly simple but dangerous.

He would awaken on the hilly, traffic congested

and black diesel smoke filled streets of Tegucigalpa

and

begin begging for money. "I would accumulate around 40

Lempiras ($2.70)," Reyes now 7, remembers. Next the

money would go for Gerber baby food jars full of shoe

solvent glue known by its trade name Resitol.

The day would be spent in the cloud of a glue

high, the eyes glazed over and unfocused. It killed

the hunger pains, erased the cold at night and made

the blows of the older kids easier to withstand.

Sooner or later every day those blows would

almost always come. "It was a very ugly life," he

says. "The big people would always beat me. There were

lots of thieves."

When the need for food would finally come Charlie

could usually get a few scraps at a Burger King. "I

never spent money on food," he stresses. The glue

demanded every cent he could accumulate.

It was six months ago that Charlie walked into

the medical clinic at the Casa Alianza center for

street children in Tegucigalpa. He was soon out of his

glue stupor and safe from the blows of street

predators. Now eyes shiny clear, Charly mixes

schooling and athletic activities with a home-type

environment at a Alianza shelter home.

But unfortunately, Charly's place on the street

has already been taken by many new arrivals. Each day

one or two new children land on the streets of

Tegucigalpa, a city of 1.5 million.

Many are collateral damage from Hurricane Mitch.

The 1998 Hurricane took 6,000 lives, left 8,000

missing and caused 1.5 million homeless. Half the

dead, missing and homeless were children, according to

a United Nations Childrens Fund (UNICEF) study.

The disaster is credited with causing a 15%

increase in children living on the streets.

Its gone up a lot," says Evelyn Esther Suazo

Lagos, coordinator of Alianza Shelter Houses. "It's

due to the death of parents, the greater poverty, the

lack of working parents and the number of families

living in shelters."

The number of children living in the streets (an

estimated 1,500 in Tegucigalpa and 5,000 nationwide)

has caused a cottage industry to form: the selling of

shoe solvent glue in poverty neighborhoods.

The glue is obtained by adults or older

adolescents for about 100 lempiras (7 U.S.) and then

resold in Gerber baby bottles for 10 lempiras (70

cents) Typically the dealer earns a 500 lempira($28

U.S.)profit on a gallon purchase. Many glue sales

areas are near market places and bridges where street

kids tend to congregate.

Some 95% of Tegucigalpa's street children are

glue users, says Casa Alianza Education Worker Misaela

Mejia. Consumption of 1 to 5 bottles of glue a day is

not unusual. The glue addicts risk chronic bronchitis,

body tremors, loss of motor functions, loss of memory,

brain seizures, blindness, damage to kidneys and

lungs,and leukemia.

Twice a day Mejia and a male co-worker visit one

of 42 areas frequented by street children in

Tegucigualpa and its sister city Comayaguela. They

provide first aid, health care information, informal

education and recreational activities.

"To live in the streets is to live a life that is

in suspension," says Mejia. The goal of Casa Alianza

is to get kids to voluntarily leave the streets and

enter one of several programs aimed at drug

rehabilitation, education and a safe sheltered life.

In one typical month six teams contacted 345

street children. Of those 85 chose to enter various

programs from emergency medical treatment, and

six-month crisis recovery stays to family

reunification and halfway house residency where

children can live until age 18.

In January a drug rehabilitation farm began

operation to provide treatment for serious addiction

patients. Crack cocaine is less evident than glue but

is making some impact, mostly among older adolescents.

"The youths that mention use of this drug are between

16-18 years old. And they are youths that usually have

gone to other countries, especially Guatemala. The

children from the streets of Tegucigalpa talk more of

glue and marijuana," says Ones Italia Garcia, head of

psychology therapy at Casa Alianza.

Most Children become street dwellers because of

family breakup,typically abuse from a step parent or

abandonment. Other children working in the streets as

vendors become enticed to runaway. The economic

pressure of Hurricane Mitch has increased this family

disintegration.

"My family life wasn't bad. I was beat at times,

but I knew how to handle it, says Marvin Matute

Martinez,15. "I got drawn to the streets by my

friends. But really they weren't my friends. They were

nothing." Matute spent age 6 to 9 on the Tegucigalpa

streets before being accepted into a shelter house

five years ago. He will be allowed to stay until age

18.

"Thank God it happened. Because I have learned a

lot about getting ahead. I'm studying now, and I'm

going to try for a profession. If I had stayed in the

streets I probably would have died. Who knows what

would have happened."

In addition to drug addiction, street children

are routinely lured into prostitution.

"Seventy to 80% of the people we see have been

involved in prostitution," says psychologist Garcia.

"The boys don't like to talk about it. But over time

it comes out."

HIV positive cases are increasingly being

identified in Alianza health screenings. In 1999 one

19-year-old woman who had been a street child and

prostitute died. Six other HIV positive youths have

been diagnosed three men and three women age 16 to 19.

One of the those, a 16-year-old girl will have a baby

in January. It is hoped, Alianza Doctor Nelson Reyes

says, that the baby will be saved from AIDS infection

by the early diagnosis. Other AIDs infected are

suspected to have died anonymously on the streets.

For girls the pressure to prostitute themselves

often is overwhelming.

"Most of the girls don't sleep on the street,"

says Educator Mejia. "Prostitution gives them money

for a room, food and drugs."

The young girls routinely produce severely

underweight babies. Other infant complications include

respiratory problems, anemia and skin infections.

Exacerbating the rough life on the streets is a

traditional disdain for street children by Honduran

Police and other sectors of society. Last year Casa

Alianza won commitment from the United Nations High

Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson to

investigate the murders of children and adolescents in

Honduras. Some 50 suspicious youth murders have

occurred in 1998. And there has been no effective

prosecution. The Honduran Human Rights Attorney

General has alleged that death squads established by

prominent Honduran businessmen were behind at least

some of the killings.

Casa Alianza cites the April 10, 1999 murder of

Alexander Obando Reyes who was shot dead by a

policeman following an argument. "The policeman opened

fired at the ground with his rifle for unknown reasons

and one of the bullets struck Obando. We identified

the policeman and obtained positive ballistic matches

for the rifle but the policeman has fled and the

Public Ministry's office has failed to issue an arrest

warrant," says Casa Alianza Attorney Rolando Quinones.

Obando, 18, had been in out of Alianza programs for

years and had recently returned to the streets in a

relapse.

The problems facing street children are

overwhelming and the assistance available meager. But

the 12-year-old Casa Alianza continues to seek

corrective measures where in the past few thought

remedies were possible.

Social workers scout for bars using underage

prostitutes and seek prosecutions. To tackle the glue

problem prosecution efforts (Beginning in 1996 selling

glue to minors became a crime under the Honduran Penal

Code) are coupled with a campaign to have shoe

manufacturers and repair shops switch from using

Resitol to nontoxic water based

glues.

One firm which went along is Fabrica Calzada

Caprisa which switched to water based glue in 1998.

Henry Rodriguez, production manager, told Casa Alianza

that the change was made both because of the physical

and psychological damage to street children using the

solvent and because of the health problems being

suffered by plant workers.

It is hoped that over time the change in

manufacturing procedures will reduce the availability

of shoe solvent glue. Alianza also wants enforced a

1989 Decree calling for all glue to have mustard oil

which makes it difficult to inhale comfortably.

Other efforts include a mom and baby shelter

program which provides training and medical care to

adolescent mothers until their baby's are five years

old.

To improve police interaction with street

children, Casa Alianza has begun training sessions for

Honduran Police. About 300 police have completed the

course. "Before they would do things to the kids like

take their glue and pour it over their head and hurt

them. Now we have more police sending kids to Casa

Alianza," says Mejia.

During a year, Casa Alianza will manage to assist

in some way about 1,300 children. But with 74% of

Honduran families ranked as poor, with most headed by

women in precarious financial situations and with 28%

of the population beginning work at the age of 12, the

streets of Tegucigalpa are expected to continue to

draw hundreds of abandoned children for some time to

come.

###

These Honduran Street Children found an

alternative to misery in a Caza Alianza shelter home. Front Row from Left, Noel Ruez, Marvin Matute Martinez, Josue David Almendarez. Second Row from Left, Miguel Antonio, Charly Reyes. Back Row from Left Evelyn Esthere Suazo Lagos, Shelter coordinator,Roger Lindersay Figueroa, educator, Aida Martinez, cook.