| en español | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

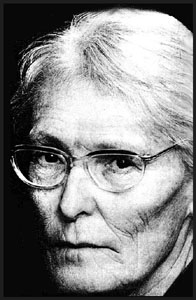

To the memory of Maria Reiche |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

PREFACE |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The

Nazca Lines are one of the greatest enigmas that the ancient world has

left for humanity, just like Stonehenge, The Giants of Pascua Island, The

Great Sphinx and different wonders of the world.

Since their discovery the enigma surrounding them has always

powerfully attracted the attention of archaeologists, mathematicians,

astronomers, UFO seekers and the curios general public.

Why and who covered kilometers of desert with straight lines,

gigantic trapezoids and what is more amazing, dozen of sophisticated

figures that can only be seen from the air?

This and other questions have promoted fantastic and audacious

theories. Scientists,

who have the highest authority on this subject, think very carefully and

with certain skepticism, where as archaeologists think that it is not

possible to answer such questions. We

understand this way of thinking because there is very poor data to make

conclusions; the Nasca Lines enigma is enticing but sometimes it is better

just to leave it without answers than to offer theories without evidence. We hope that the Epistemology of the future will allow

us to obtain the proof, as without them, the so important and gaudy Nasca

enigma will remain deeply considered by very few scientists, as most of

them prefer to walk by securer routes than risk themselves falling on

dangerous ground. If

we had followed this way of thinking, this present book would never had

seen the light. As to

surrender without a fight is easy, but doesn’t deserve our admiration.

A great enigma is a challenge for any cultivated mind…so…we are

going to decode it or at least let’s make a fool hardly attempt as it

doesn’t matter if we lose. There

are many different published theories about this astonishing monument,

probably the most famous belonging to Dr. Maria Reiche, in whose memory we

dedicate this present book. Her

interpretation links the Nasca Lines with astronomical observations and

the figures with the constellations.

This explanation undoubtedly is determined by the doctor’s

profession, Mathematics. Her

theories can be argued but it is certain that without her work the Nazca

Lines and the geoglyphics would not have survived to this day.

It is also to true that she knew the field more than anybody,

because for many years it was her home and studio. Now

the most popular version belongs to Johan Reinhard. His theory is opposed to Maria Reiche’s, as an

‘anthropological’ point of view.

According to him, the lines point to the Sacred Mountains

‘suppliers of water’ and that the entire pampas of the geoglyphics

would have been a great scenery for fertility ceremonies. There

are also a series of different theories, which present us with more less

argumented theories, but from our point of view all of them have the same

fault, as they are radical. An

author proposes an idea and sets it up against another, canceling out the

possibility of a ‘multiple interpretation’.

Is it not possible that some lines could point to the stars and

others to the mountains? And

at the same time a constellation could be a divinity? The

present book offers a spectrum of ideas and interpretations about the

Nazca Lines general monument and also to its particular parts, some of

them are ours and others come based on previous studies.

We are offering you the job my dear reader to keep and reject which

you like. The structure of

the book allows you to combine them as you will.

Even though, early in the book some appear contrasting they become

complementary and are all an important part of the topic.

Based

around four subjects, being the first about the myths, rites and cultural

heroes in Nazca. We are lead

also to the Moche culture on the Northern Peruvian coast. These two cultures shared the same ecological conditions,

similar patterns in economy and probably deep similarities in their

mythology and Cosmovision. The

mythical scenes on the Moche pottery give us abundant material to find

analogies with the Nazca geoglyphics. The

second part leads us to almost a thousand years later to the Incas.

This is the earliest age we have written texts of myths and legends

at the Spaniards chronicles. Although

the time distance between the Nazcas and the Incas looks huge,

other written evidence of the lives in the Andean world is not

available. Although we can

discover ‘Inherited characteristics’ as the Incas summarized knowledge

of previous cultures. The

third and the furthest arrives the modern Anthropology, the present-day

Peruvian society have nothing from their ancestors, but in some cases the

isolated communities give us astonishing analogies, and the expression

‘time has stopped’ is true.

This first part of the book is based around a central concept the

notion of fertility, which in the inhospitable Nazca land should be of

vital importance. The

second part of the book the astronomical interpretations are placed

together, they object the

first half of the book, as the astronomy in the ancient societies did not

exist as a free and independent science, it rather was a part of their

mythic Cosmo vision. The star

movement’s studies were necessary for the calendar creation, which were

used as a rule for the agrarian circle, so the stars were in strict

relation with the earth’s life and the astronomy with the fertility

concept. The

last part introduces us the enigmatic Shaman, the ancient cultures wise

man, medicine-man, magician, priest.

He was probably the creator of the Nazca Lines wonder and the

guardian of its secrets. Here

we inquire into the Shamans most powerful instrument, The Hallucinogenic

plants, and its possible role in the geoglyphics creation.

I must publicly thank Dr. Carl Sagan who helped me to find

resemblances between the magic world of the Shaman and the Quantum theory

discoveries like ‘Uncertainty Principle’ or ‘Parallel Universe’. Also finding a new explanation for the UFO phenomenon, which

is nowadays closely linked with Nasca? I

honestly confess that in many cases I’ve let my imagination lead me more

than the facts (basically because the absent of the latter’s). Let’s not forget that imagination is the best weapon when

we invade unknown territory. Remember!

Einstein left us with the harangue: “Imagination

is more than knowledge”, even though the latter would be indispensable

for scientist rigor…SO…TO ARMS, MY DEAR READER! A real great battle

awaits for us…

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INDICE

LA ESPIRAL: VIAJE AL INFINITO

FUENTES DE ILUSTRACIONES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chapter 1 WHEN THE GODS MAKE LOVE

Nazca, February 25th 2001 - 04:08 a.m.

The trucks came to a boistorous stop in the small town of Pangaravi, at Luis Bueno's doorstep, the engineer who had invited the "Nazca lines decoded" task force to be a part of the Yunza celebration. Equipment, provisions, and other things were shuffled at flashlight's glow. Following a deserved rest which stretched almost until noon, we got together in the room they had prepared for us at the fair. I was startled to find a tree "planted" at the centre of a wide yard. In it hanged all sorts of small gifts of different sorts, like so many fruits. You could see notes, baskets full of tempting products, especially for the ladies, it reminded me of a christmas tree, only gigantic and with the presents way up there, out of reach. All of sudden, a band broke the routine with a melody from the Ayacucho and Apurimac region, in the Peruvian sierra. Several groups of people were dancing in ritual manner, surrounding, approaching and receding from the Yunza tree.

Lucho grabbed us by the hand, pulling us in a snake-like dance, and converted us in the newest members of this mysterious brotherhood. Followingly, all the groups joined hands to form a great round which girated to the sound of the trumpets and the drums that surrendered the tree. The couple who had organised the celebration were dressed up as hummingbirds, with and axe in hand, pulled out of the round to approach the tree, and proceeded to hit the tree as if they intended to chop it down. Afterwards, while dancing in a more ceremonial manner, they passed the axe down to another couple, dressed as monkeys, who repeated the same exotic snake movement to their own style, only to hit once again with the axe, slightly shaking the cup full of riches. This raucous commotion unraveled beneath an incandescent desert sun, which concluded at the end of an infinite horizon from which poured thousands of magical tones of red and screaming yellows blurred in the sky over Nazca. I do not remember in which of the dances, but it was already at night, a "paracas" wind suddenly broke the already worn down trunk, and the tree fell over the iguana men. Women, men, children and elderlies, all threw themselves to storm the tree and the unfortunate "iguanas", fighting over the spoils, and the fiesta came to an end. The fox couple, who held the axe at that moment, turned pale knowing they would be in charge of the celebration next year, even as they smiled knowing that everyone of us would participate in it.

As I tried to understand the meaning behind the Yunza feast, I learned that it came from the Ayacucho region, very likely from Wari roots. (23) From the date (the rain season) and the type of ceremony, we can derive the disturbing interrogation, just what did the Andean men have to reap the fruits symbolised as gifts...In order to further the investigations, I pointed my dusty steps towards the Rafael Larco Herrera Museum, where inside the "erotic room" of an excellent exhibit, one can appreciate one of the most commented upon scenes of Mochica art, on ceramics, which depicts sexual copulation between a mythical being (the primordial snake belt) and a woman (Fig.1). On one side can be seen the mythical dog and iguana; an anthropomorphical bird is pouring a liquid over the lovers. This scene has already been analysed by Anne Marie Hocquenghem.

Among the thousands of *moche* jars, all painted with perfect technique and a wild imagination, certain scenes return over and again. Past research has shown that these scenes hold a special importance in the mythology. Ours is one of them. Its most complete version was published by Carrion Cachot in 1959. In it one can also see two women in a house on the side. They also appear to be waiting for the mythical being's visit. A crucial detail of this scene can be observed on another piece of pottery within the same Larco Herrera museum.(Fig.2): a tree sprouts from the couple, in whose branches laden with fruit can be seen various monkeys. This detail leads us to a concept of utmost importance to all the agricultures of the world: the idea of soil fertilization.

In order to understand its meaning, I opted this time to point my dusty feet towards the Biblioteca Nacional (National Library), where I undertook to review the chroniclers' books, as they had recompiled folk versions of Andean myths and rituals about copulation between mythical beings and women. Molina tells us in 1575 that a woman, a sister or daughter of the Inca, sacrificed to the sun, played the role of the sun's woman. We can also associate to this what Guaman Poma explains about the month of September, when was held a great ceremony to the moon (coya raymi), because the moon (who is the sun's wife) gets together with the sun during that month. During the festivities, the principal women "treat the men" (Molina 1943).

As one reads Francisco de Avila, in his collection of Huarochiri myths, I stumbled upon a myth that I consider essential to this study, since it is directly related to the Nazca lines: it tells us about the beautiful Chuquisuso of the *ayllu* Cupara and the *huaca* Pariacaca: "In those days, there lived a beautiful woman in the village about which we speak. Her name was Chuquisuso. One day, she was watering her corn field, crying. She was crying because what little water there was did not suffice to wet the scorched earth. At this moment Pariacaca came down and tapped the *bocatoma* of the little lagoon with his cape. The woman wept with increased pain as she saw the water disappear. Pariacaca found her in this state, and asked her: 'Sister, why are you suffering?'. And she replied: 'My corn field is dying from thirst'. 'Do not suffer' Pariacaca told her. 'I will make it so that a lot of water will come from the lagoon of your people in the heights, but you must agree to sleep with me first'. 'Make the water come, first. Once my corn field is watered, I will sleep with you', she replied. 'Very well', Pariacaca accepted. And he made it so that a lot of water came. The woman was so happy she watered all the fields, not just her own. And once she was done watering the seedlings, Pariacaca told her 'Now let us go sleep'. 'Not just now, the day after tomorrow', she told him. And since Pariacaca loved her dearly, he promised her everything, because he wanted to sleep with her. 'I will convert these fields into watered land, with water coming from the river', he told her. 'First do these works, and then I will sleep with you', she replied. 'Very well', was Pariacaca's answer, and he accepted". (25) "In those days, the yunca villages had a very little aqueduct to water their lands, it came out of a gorge named Cocochalla, a little above San Lorenzo. Pariacaca converted this aqueduct in a wide irrigation canal, with abundant water, and had it reach up to the Huaracupara men's small farms. The pumas, the foxes. The snakes, all classes of birds, sweeped the aqueduct's bottom, they were the ones that built it. And in order to do the work, all the animals got organised: Who is going to oversee the field work, who has to go in front?', they asked. And everybody wanted to be the guides. 'Pick me first', 'Me', they demanded. The fox won. 'I am the *curaca*, I will go ahead', he said. And he began the work, at the head of the other animals. The fox supervised the works, the others followed him. And when the work reached just above San Lorenzo, high in the mountain, a partridge suddenly flew away. It jumped, crying out: 'Pisc, Pisc!' The fox was startled, 'Huac!', he cried out, as he fell and stumbled down. The other animals became furious and had the snake come up. They said that if the fox had not fallen down, the aqueduct would have followed a higher path, instead of going a little downwards, as was the case. One can still see where the fox fell down because that is where the water comes out from.

Once the aqueduct was completed, Pariacaca told the woman: 'Let's go sleep'. But to this she replied: 'Let us go up to the high precipices; there we will sleep'. And so it went. They slept on a precipice named Yanaccacca. And when they had already slept together the woman told Pariacaca: 'Let us go anywhere, the both of us.' 'Let's go', he replied. And he took the woman to the *bocatoma* of the Cocochalla aqueduct. When they reached the site, the woman named Chuquisuso said: 'I will stay on the edge of this aqueduct', and she immediately froze into a rock. Pariacaca lead on upwards, and kept walking towards the summit. We shall discuss this later. In the *bocatoma* of the lagoon, just over the aqueduct, is a woman of frozen stone: she is the one that was called Chuquisuso'. (Avila 1966, *cursivas nuestras*). (26) ...Do you notice how Pariacaca builds the aqueducts with the help of pumas, snakes, and all classes of birds, guided by a fox, who "sweeped" the aqueducts? All of them are drawn as geoglyphics in Nazca. This drama fits very closely to the reality of the desert, with the problems of obtaining water and irrigating the cultivated fields.

Dr. Maria Reiche proved that the technique most used to construct the geoglyphics was that of the "sweeping" (removing the rocks from the surface). The legendary tale of the animals getting together to 'sweep' the aqueducts and choosing the fox evokes the possibilty that the Nazca geoglyphics could be a kind of plan for the project of irrigation aqueducts for which all the animals were present, including the fox, of course. (Fig.3) We will back this thesis with a quote from Johan Reinhard: "There, we found that each line that radiated from a mount ended up crossing one of the irrigation channels, at points where the latter changed direction". The religious or ritual character of the geoglyphics appears to be verified by the presence of a central place of cult (the mount) which connects to key places in the irrigation system through the lines. Was it in Nazca as some kind of eternal memory of the myth of Pariacaca, or as the ideal place to practice the rite of such mythological epic...?

The discovery of the Pariacaca and Chuquisuso myth leads us to seriously reconsider the studies made by David Johnson over the last five years, backed by the National Geographic Society and the University of Massachusetts. Maybe he was received with a certain scepticism because he arrived rigged with a metal wand that blindly pointed him sources of underground water (the radiesthesis method), as is usually the case with this sort of things, although in another domain it provoked interest. According to Johnson's theory, the geoglyphics are at least partly a map of the underground *acuiferos* that feed the filtering galleries of Nazca. The geographic faults that abound in the area, thanks to the movements of the Nazca geological plate, act as 'tubes' through which the water enters the valleys by the sides, perpendicular to the rivers flow. Johnson remarked that the ancient aqueducts and archeological sites are linked to these sources of underground water, and not to surface water.

The ancient inhabitants of Nazca, Johnson tells us, knew how to detect and use these *acuiferos*, possibly through the same radiesthesis method, and that they indicated their location by drawing geoglyphics in the ground. "More complete studies carried out in the four valleys of the Nazca hydrographic basin came to the same conclusion: the Nazca lines clearly describe the source and flow of the *acuiferos*. They constitute an open book in the scenery that provides the area's inhabitants, ancient and actual alike, with the solution to their problems with water...Following two years of research in Nazca, I am convinced that the ancient dwellers accurately detected the area's *acuiferos*. It is very likely that they, too, found them using the metallic wand (radiesthesis). They studied the zone's geology and associated its geological features with the sources of underground water clearly marked with a variety of geoglyphs...Although this theory may well not apply to all the lines, it does correspond to many of them". (Johnson 199..)

In this '*acuiferos* map', different types of geometric lines and figures would have different meanings: "For example, we find trapezoidal quadrilaterals directly above the faults, and the base of the *trapeziums* defines the width of the fault area capable of providing (28) water in concentrated flow. The triangles, or arrows, point to the areas where the faults cross mountain peaks or summits" (Proulx, Johnson and Mabee 2001). The lines have multiple interpretations; for example, they can outline the edges of the *acuiferos*, or connect other important symbols together. One interesting though less supported explanation refers to the animal figures. Johnson supposes that they are the 'names' of the acuiferos, and that their size reflects the importance of the respective underground streams (Personal Communication).

Aveni discovered that the lines and trapezoidal quadrilaterals are oriented in close relationship with the direction in which the water current flows. Smart. Most of them run parallel or perpendicularly to the river current. Katarina Schrieber suggested that the trapezes located on the edge of the pampa point to the slopes leading to the river, indicating 'paths to the water'. Rossel Castro, in 1977, offered: "In the Nazca galleries were found, inside the sewers or 'underground tanks', a jug or pot magnificently decorated of a classical type, or a gobelet of gold standing as an idol of the god of the waters: 'The Otter'. These galeries are found to be in intimate connection with the geometrical figures outlined on the surface of the ground where the galeries originate...On the mounts of these figures, I also found remains of the Nazca civilisation. For all these reasons, the filtering galeries in that area, being the culmination of a long process, belong to the 'classical Nazca', between the years 330 B.C. and 500 D.C.".

In 1968, researchers Craig and Psuty discovered six lines running from a mount while analysing aerial photos of the Pisco river's right margin. Every one of them "cuts" transversally one of the main irrigation canals, where the latter change direction. The authors arrived to the conclusion that it was, more than sheer chance, because the lines could be related to the measurements for the construction of the irrigation system. (29) In 1947, H. Horkhermer told us that the geoglyphs' elaboration is due to various generations of dwellers, and explained that stripes several kilometers in length were not necessary for astronomical ends, since short lines would have attained the same objective of establishing the exit or the vanishing point of a star; moreover, many lines point to the North or South, where you never see the golden star. For his part, Sidonius, in 1968, expressed that he could not imagine that they were only interested in the study of calendar science; much less if such gigantic and laborious work was neither practical nor useful.

Between 1967 and 68, The Astrophysical Observatory of the Smithsonian Institute sent six expeditions to Nazca , under the direction of G.S. Hawkings who declared that out of the 186 directions studied, only 39 coincided with the extremes of the sun, the moon, and the most shining stars, and that the 80% remained without an explanation. After having looked for all the astronomical possibilities with the help of a computer, he concluded that the geoglyphics as a whole cannot be said to be of an astronomical nature. He adds :"The lines are useless to observe the exit of a star, as they are invisible at night...We could not find lamps or remains of bonfires to point out the trails. Furthermore, gleaming blazes would only obscure the star's weak appearance".

"There is, however, an interesting exception. The number of lines oriented towards the sunrise and sunset at the end of October and the middle of February is 50% higher than what you would expect from a totally random distribution. The dates mentioned maintain a close connection with the cycle of the water's avenues. The first rains in the mountain usually fall between October and November. Traditional farmers look for Nature's signals during October to assess future precipitations. Towards mid-February, the water in the rivers reaches its higher levels" (Makowski 2000).

In 1974, Maria Reiche declared: "Moon lines are more common than Sun lines". G. Petersen contributes: "On the coastline, the Moon and the fertilizing power of water are connected, which is depicted on the ceramics as if it was pouring water over the earth. Among the Chimu, the Moon deity carries jugs full of water", and Josue Lancho, the Nazca professor well versed in its history, found various lines that end up in the water sources.

The filtering galleries were of utmost importance, because they produced more than twenty percent of the water necessity, even as the river dried out some months of the year. It consists in a work of similar magnitude to that of the lines: almost 6 000 m. of filtering galleries and 11 000 m. of canals must have required an extraordinary push, given that it was built in open ravines up to 10 m. deep. Once the stone and wood was set, the ravines needed to be filled with the same volume of excavated earth. Although they only had primitive tools, the galleries were brilliantly finished, as even today, after 1 100 years, they water over four thousand acres of land.

In 1980, G. Petersen expressed the following: "From the hydrological point of view, it is noteworthy that the Cahuachi II (Nazca), interpreted the galleries and channels towards which the water table filtered, like underground springs, and thus as key points for all sacrifices to the water deity. This concept endures until now, given that farmers to this day call the filtering galleries Puquios, a quechua word meaning spring and source. Since there are no other town with pre-columbian age filtering galleries that we know of, we can consider Cahuachi II to be the only place on all the Peruvian coast where this cult would have been practiced".

The analysis carried out by Dorn to put a date on the lines was repeated with the stones taken from the roofs of some of the undergound aqueducts. The date obtained is 550 D.C. approximately, which proves that they really were built during Nazca times. Another detail: the maps of the ancient populations show that during the early stages of the Nazca culture, people only lived on the higher part of the river, where there is water all year round. But as time went by, new populations appeared down the river, where water is scarce, and where their existence would be impossible without artificial irrigation through the aqueducts. All this data shows that the filtering galleries were built by the ancient Nazcas.

Alberto Rossel Castro, the local priest, propsed a very audacious hypothesis, according to which the geoglyphics plain was the area cultivated anciently; the 'plazas' or trapeces were really farmland, and the lines, the plan for the irrigation galleries for these fields. The Rossel Castro version was rejected for being too 'extremist', but recently arqueologists found several 'sweeped fields' or 'models' near the edge of the pampa, cleaned up spaces that look just like real cultivation fields. Helaine Silverman thinks that these 'symbolic fields' could be the prototype which led to the whole geoglyphics tradition.

It is curious that Paul Kosok, the astronomical theory's famous author, would have taken the lines for irrigation canals when he first saw them from a plane, or that Maria Reiche, a relentless defender of the astronomical thesis, according to "Die Welt", No. 89 published April the 27th 1979, during a conference titled: "Origin and Meaning of the Nazca drawings", stated "that the drawings in the plains of Nazca were built with an agricultural purpose"...(?). For this and the reasons previously discussed, we could infer that more than astronomical, the lines were in fact connected to the water that came to Nazca through the irrigation canals, as a great majority of the lines seem to indicate.

According to Anthropologist Frank Salomon's interpretation of the Huarochiri myth, the descent of water from the mountains, as well as the rain, both have strong sexual connotations in which that from 'above' (the sky and the mountains) represent the masculine part, while the earth is the feminine part. In Nazca we find another myth which symbolizes a relationship between deities of different genders: (32) "Illa-kata was the lord of the heights. Tunga, the lord of the coast, became his friend and brought him presents of gold, gems, cotton blankets and ceramics. Tunga was deceiving Illa-kata's wife, having her believe that he had been sent by the ocean god who fertilized the fields and produced animals. He convinced her that she could leave behind thunder's bad temper, the cold nights, and the thick clouds. They eloped while Illa-kata was asleep, making a run for the sea. Upon waking up, Illa-kata realised that his woman had gone, and he called her with a thunderclap. She heard it and understood that it would reach them and so pleaded with Tunga to let her die on the spot. Tunga, however, covered her with corn meal from his valleys, in order to disguise her. Afterwards, when the heat of the sun made it impossible for Illa-kata to pursue his search, Tunga thought about going back to her side. Later on, Illa-kata dropped by, but he didn't recognize his wife, and he went back to his hills, where in his anger, he caused great earthquakes with the intent to destroy the lesser hills. His wife became trapped under the rocks and so too Tunga was transformed in a hill just as he was about to make it to the sea." (Reinhard 1998)

Although this myth does not illustrate directly a sexual relationship because of its tragic end, deep down we can understand the occult meaning of fertilization. Thus, the coast god tries to steal the mountain range's fertility. The inclement droughts they always had to face, combined to the sea gods' influence, all must have contributed to the creation of such drama.

Myth isn't only a story, it also serves a practical purpose, ordering society in its everyday labour. The latter justifies the agricultural calendar, essential to survive in the hostility of the desert. In Andean cosmovision, the water is the ancestors' blood that they let run so that men may live. The latter, in turn, must carry out rites that are repeated over and over, in accordance with the appearance and disappearance of certain constellations. They must organize in precise moments of the agricultural year's progress, for example, with the purpose of cleaning the (33) irrigation channels, or other important moments in the crop cycles, or even hunting. This succession of seasonal rituals is rather similar and uniform all across the Andes. (Ossio 1978)

Even today is celebrated a modern version of the Fertility Rite called Yarga Aspiy, in the Ayacucho region. It is the feast of the water in the irrigation canals, considered to be an act of purification. In the village of Chuschi, water is thought to be a masculine element which comes down to fertilize the earth. At the time of the September equinox, a ritual act of copulation is performed: the Wamanis, who live in the summits that dominate the village and see over its destiny, come down along the canals while a young and "purified" bride, personifying the earth, climbs up to meet them. In the village of Huarochiri, under the pretext of the same fiesta, the ancestor Huari is represented by an actor laden with feathers going down along the canals while a young girl climbs up from the cultivated fields to meet him (Isbell 1978; Dumézil y Duviols 1974-76). The natives explain that the earth "opens up" before the equinox during "dangerous" days and that it is fertile by the time of the Spring equinox (Isbell 1976).

Going back to the beginning of this chapter in order to analyse more closely the Mochica scenes of the union of the ancestor and the woman, we can observe the presence of the mythical characters and elements: the huaca, the woman, the hombrecillos, human remains, the women who may represent various *ayllus* waiting to 'be watered' or fertilized by the huaca (who would be the source of water), the zoomorphic helpers, among them the iguana and the dog. There is also the container out of which a bird is pouring a liquid, which could be taken to be the announcement of the rain season, but definitely demonstrates that the condition for its appearance would be the sexual relation between the god and the woman.

Anne Marie Hocquenghem correctly interprets the hombrecillos as the woman's family, and the human remains as the confirmation that the women (34) were indeed sacrificed to the ancestor, although she cannot find any interpretation for the pot in which 'something' is prepared (Fig.1). Because of the ritual character of the scenes, I will suggest that the preparation is possibly psychoactive plants, which could have played an important part, especially in these rituals, because of their power to put us in contact with mythical worlds ordinarily invisible to us.

As we move on to the next figure, we can see that from the union of both beings sprouts a tree with fruits and monkeys (Fig.2), it is easy to understand that it is the expression of the result of the union between the ancestor and the woman: abundance, the result of combining water with earth. It would refer to the initial act of fertilization of the agricultural year, essential to the world's reproduction.

The Moche and Nazca cultures, in addition to being contemporary, given that we may already have them share many cultural elements, such as the social structure, mythology, basic concepts and technology; they also lived in very similar ecological environments (desert coast), which would determine identical modes of production for both societies. We can add to that their geographic proximity which allowed for a fluid communication, the same one that I guessed in a strange parallelism of their cosmovision. (Walter Alva: Personal Communication). So that it may be justified to state that their cultural expressions were very similar (although each with its own personality), their agricultural calendar as well as the ritual must have been the same, since they both had to wait for the rain in the Andes. Accordingly, through the concept that the Moches gave to the tree, we could find the meaning for the tree-shaped geoglyphic in Nazca.

There is one detail of utmost importance: there are geoglyphics on the North coast, just like in Nazca. "Paul Kosok, thanks to whose work the geoglyphics have become famous, became aware that similar shapes can be found scattered in the Central Andes all the way to the Lambayeque valley" (Makowski 2000). Silva Santistevan corroborates: "...with similar techniques there are various additional figures...maybe the most typical is that of the "Condor" which corresponds to a model of *falconidé* represented in the Paraca-Nécropolis fabrics; it is done in haut-relief and it recalls another famous "Condor of Oyotun", at the limits of Lambayeque and Cajamarca".

Thus, it can be understood that the act of sacred copulation would be represented in the Nazca desert, in symbolic form from the presence of a gigantic tree 45 meters long, known as 'the Huarango' which for all previously expressed connotations, appears to be the "tree of life", accompanied by an iguana, the mythical iguana (Fig.4). I must add that the tree in Nazca appears with five visible roots, a strange occurrence whose meaning we will clarify in the chapter "Life is a game".

If we ponder these facts a little, we will realise that this myth must have given way, within the village, to a ritual carried out in the hope that the god would find the virgin to his taste, and that his sexual intoxication would somehow spread to the sky, out of which the rains come and germinate the 'tree' which they had succeeded in cultivating in perfect community with all the animals (who had fought the desert as well). "And following this time, from the Llantapa mountain sprouted a tree called Pullao who picked up a fight with the other mountain named Huicho. Pullao was like a gigantic arch, and upon it the monkeys, the birds, the caqui, and all the birds had taken refuge." (Avila 1966) And never again did they suffer from hunger nor can be heard whimpers of pain and sorrow on the earth.

copyright - Colin Turcotte - This version, all rights reserved - August 2006 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

BIBLIOGRAFIA |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| For more information about the distribution of the book: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| nazca_decoded@yahoo.com | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| nazca2001@latinmail.com |