track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

track 1. Honeysuckle Rose: track 2. Blue Turning Grey Over You: track 3. I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby And My Baby's Crazy 'Bout Me: track 4. Squeeze Me: track 5. Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now: track 6. All That Meat And No Potatoes: track 7. I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling: track 8. (What Did I Do To Be So) track 9. Ain't Misbehavin':

|

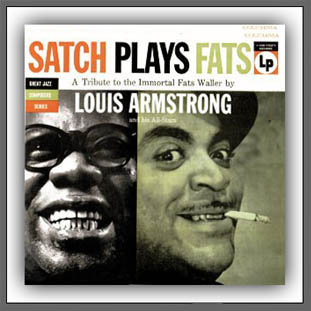

Satch Plays Fats

Louis Armstrong & His All-Stars

Columbia Records LP Photography - Art Maillet

trumpet - Louis Armstrong

producer - Tommy Rockwell

|

| Humphrey Lyttelton's Original 1955 LP Liner Notes... | |

|

________There can be few performers in the history of music who have, both during and after their lifetime, attracted myths as readily as Louis Armstrong (bio). The myth makers were at it fifty years ago when, as a schoolboy, I used to snap up every new release by Louis Armstrong and his big band and marvel at the beauty and majesty of the trumpet playing in numbers as diverse as "Struttin' With Some Barbecue" and "Yours And Mine".

________"...ah yes..." the reviewers would say, "....but this is a mere shadow of the Louis of the twenties. Now he's playing to the gallery, whereas the Hot Fives and Sevens were pure art...".

________Well, history's verdict has been "Fiddlesticks!" If, for the sake of argument, we leave on one side the seventeen days, spread over three years, which it took to record the entire output of the Hot Fives and Sevens, ________Ancillary to the myth of Louis Armstrong's decline was one which claimed that, under pressure of commercialism and in the interests of an easy life, he "...gave up improvising...". Once again, history comes down heavily against this view. The testimony of contemporaries, of Louis Armstrong himself, and of those alternative versions of early Louis Armstrong that exist (the Hot Seven titles "S.O.L. Blues" and "Gully Low Blues", in fact two versions of the same piece, are a prime example) show that his favored method was always to establish a basic pattern for each tune to which variations would be added as time went by and circumstances altered. There was a time, he used to say, when as a young man he would "...play all those notes like the boppers do today...". But the injunction of his precursor and mentor, King Oliver, to "...just stick to that lead..." clearly made a deep impression. ________During one of Louis Armstrong's visits to Britain in the late fifties, I attended a lecture given by Mezz Mezzrow at The Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. At question time, someone raised the point about Louis Armstrong playing exactly the same night after night, year after year. Mezz Mezzrow, always a ready champion of Louis Armstrong and a judge of some perception, came back strongly. ________"...people who say that don't really listen..." he said "...sometimes the variations will be in the phrasing rather than the notes, but those solos are always changing, depending on the tempo, the atmosphere, or who's playing with him at the time...".

________There is a further point to be made which is relevant to this collection. Supposing the solos had never changed in any way perceptible to the human ear? The early jazz writers who enshrined "improvisation" as a criterion in the definition of jazz very soon found themselves hoist with own petard. Where to put performances such as Duke Ellington's "Rockin' In Rhythm", with its set clarinet solo and written ensembles? Indeed, how did arranged or composed music qualify at all, even when the end result sounded like jazz and nothing else? Duke Ellington himself came up with the best answer years later when he said "..I can never understand why this thing that people call jazz should take precedence over ME!.." But rather than scrap the awkward category altogether, the pundits preferred to modify it by admitting set music that "retained the air of spontaneity". ________By this criterion, "Satch Plays Fats" was always wonderful jazz. While others have said that, during The All-Stars period of the fifties and sixties, the constant touring with two shows a night led inevitably to jaded, routine performances, I have found myself marvelling at the sustained intensity and verve with which the most familiar material was attacked. I never heard a version of "Black And Blue" that failed to move, ________There are imperfections, of course. "All That Meat And No Potatoes" was one of Fats Waller's (bio) most off-hand concoctions, a jingle that almost defies Louis Armstrong's noted capacity for making bricks without straw! Velma Middleton, bless her, was not the greatest of singers, nor was she helped here by having most of the songs seemingly pitched well below her natural range. And it was always apparent that, by the mid-fifties, Barney Bigard's batteries were running flat and needed a change of scenery to recharge them. It would be quite understandable if he felt overwhelmed by the combination of Trummy Young's boisterousness (bio) and the enthusiasm which it clearly kindled in Louis's playing! ________It is also implicit in a collection which includes alternative takes that there will be flaws that prompted the remake in the first place, though these often turn out after the event to be negligible. In sorting out what is fresh material and what was on the original album, complication arises from the fact that there was obviously cross-splicing on some numbers -- for example, the final master-take of "Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now" must have been a veritable patchwork quilt of adhesive tape!

1) Honeysuckle Rose:

2) Blue Turning Grey Over You:

3) I'm Crazy About My Baby & My Baby's Crazy About Me:

4) Squeeze Me:

5) Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now:

6) All That Meat & No Potatoes

9) Ain't Misbehavin': | |

|

| |

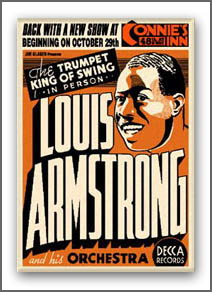

Louis Armstrong: a bio... _____Louis Armstrong was born on August 4, 1901, in New Orleans. He is considered the most important improviser in jazz, and he taught the world to swing. Louis Armstrong, fondly known as "Satchmo" (which is short for "Satchelmouth" referring to the size of his mouth) or "Pops", had a sense of humour, natural and unassuming manner, and positive disposition that made everyone around him feel good. With his infectious, wide grin and instantly recognizable gravelly voice, he won the hearts of people everywhere. He had an exciting and innovative style of playing that musicians imitate to this day. Throughout his career, Louis Armstrong spread the language of jazz around the world, serving as an international ambassador of swing. His profound impact on the music of the 20th century continues into the 21st century. _____Louis Armstrong was born on August 4, 1901, in New Orleans. He is considered the most important improviser in jazz, and he taught the world to swing. Louis Armstrong, fondly known as "Satchmo" (which is short for "Satchelmouth" referring to the size of his mouth) or "Pops", had a sense of humour, natural and unassuming manner, and positive disposition that made everyone around him feel good. With his infectious, wide grin and instantly recognizable gravelly voice, he won the hearts of people everywhere. He had an exciting and innovative style of playing that musicians imitate to this day. Throughout his career, Louis Armstrong spread the language of jazz around the world, serving as an international ambassador of swing. His profound impact on the music of the 20th century continues into the 21st century._____Armstrong grew up in a poor family in a rough section of New Orleans. He started working at a very young age to support his family, singing on street corners for pennies, working on a junk wagon, cleaning graves for tips, and selling coal. His travels around the city introduced him to all kinds of music, from the blues played in the Storyville honky tonks to the brass bands accompanying the New Orleans parades and funerals. The music that surrounded him was a great source of inspiration. _____A born musician, Louis Armstrong had already demonstrated his singing talents on the streets of the city and eventually taught himself to play the cornet. He received his first formal music instruction in the Colored Waif's Home for Boys, where he was allegedly confined for a year and a half as punishment for firing blanks into the air on New Year's Eve. As the young Louis Armstrong began to perform with pick-up bands in small clubs and play funerals and parades around town, he captured the attention and respect of some of the older established musicians of New Orleans. Joe "King" Oliver, a member of Kid Ory's band and one of the finest trumpet players around, became Louis Armstrong's mentor. _____When Joe "King" Oliver moved to Chicago, Louis Armstrong took his place in Kid Ory's band, a leading group in New Orleans at the time. A year later, he was hired to work on riverboats that traveled the Mississippi. This experience enabled him to play with many prominent jazz musicians and to further develop his skills, learning to read music and undertaking the responsibilities of a professional gig. In 1922, Joe "King" Oliver invited Louis Armstrong to Chicago to play second cornet in his Creole Jazz Band. _____In 1925, Louis Armstrong returned to Chicago and made his first recordings as a band leader with his Hot Five (and later his Hot Seven). From 1925 to 1928 he continued a rigorous schedule of performing and recording, which included "Heebie Jeebies", the tune that introduced scat singing to a wide audience and "West End Blues", one of the most famous recordings in early jazz. During this period, his playing steadily improved, and his traveling and recording activities introduced his music to more and more people. In 1929, Louis Armstrong returned to New York City and made his first Broadway appearance. His 1929 recording of "Ain't Misbehavin' " introduced the use of a pop song as material for jazz interpretation, helping set the stage for the popular acceptance of jazz that would follow. During the next year, he performed in several U.S. states, including California, where he made his first film and radio appearances. In 1931, he first recorded "When It's Sleepytime Down South", the tune that became his theme song. In 1932, he toured England for three months, and during the next few years, continued his extensive domestic and international tours, including a lengthy stay in Paris. When Louis Armstrong returned to the U.S. in 1935, Joe Glaser became his manager. Not only did Joe Glaser free Louis Armstrong from the managerial battles and legal difficulties of the past few years, he remained his manager for the duration of his career and helped transform Louis Armstrong into an international star. _____Under Joe Glaser's management, Louis Armstrong performed in films, on the radio, and in the best theaters, dance halls, and nightclubs. _____Throughout the 1950s and 60s, he continued to appear in popular films and made numerous international tours, earning him the title "Ambassador Satch". During a trip to West Africa, Louis Armstrong was greeted by more than one hundred thousand people. In the early 1960's, he continued to record, including two albums with Duke Ellington and the hit "Hello Dolly", which reached number one on the Billboard charts. Louis Armstrong performed regularly until recurring health problems gradually curtailed his trumpet playing and singing. _____Even in the last year of his life, he traveled to London twice, appeared on more than a dozen television shows, and performed at the Newport Jazz Festival to celebrate his 70th birthday. Up until a few days before his death, on July 6, 1971, he was setting up band rehearsals in preparation to perform for his beloved public. | |

|

| |

Fats Waller: a bio...

bottle of gin nearby, his eyebrows raised, his derby askew and a cigarette dangling from his wide, cockeyed smile. He always let you know that there was at least one more joke inside the one he had just told. bottle of gin nearby, his eyebrows raised, his derby askew and a cigarette dangling from his wide, cockeyed smile. He always let you know that there was at least one more joke inside the one he had just told._____Thomas Wright Waller grew up in the exciting musical atmosphere of Harlem in the teens and '20s. His parents were deeply religious, and Fats Waller started out playing the organ in the Abyssinian Baptist Church and studying classical piano technique. He also began working with Harlem stride-piano masters like James P. Johnson and Willie "The Lion" Smith, although his father insisted that jazz was "music from the devil's workshop". Soon he was accompanying the silent pictures at the Lincoln Theater on 135th Street and making his reputation at uptown rent parties - those all-night affairs so fondly remembered in "The Joint Is Jumpin' ". _____When he was still in his early 20s Fats Waller began his collaboration with lyricist Andy Razaf; they scored their first success in 1928 with "Keep Shufflin' ". The next year was miraculous: Fats Waller - only 25 years old - and Andy Razaf wrote the score for the Broadway hit "Hot Chocolates" (which included "Ain't Misbehavin' " and "Black and Blue") as well as "Honeysuckle Rose", "I've Got a Feeling I'm Falling" (lyric credited to Billy Rose) and a host of other distinguished tunes. It was in that same year that Fats Waller signed a contract with Victor, the company for whom he performed until the recording ban of World War II. Fats Waller's records, which began with "T'Ain't Nobody's Biz-ness If I Do" in 1922, spread his fame across the United States and around the world. It seemed that he could make any tune sound entertaining. The finale of the Broadway show "Ain't Misbehavin' ", in fact, is made up of some of the songs written by others that Fats Waller made hits. _____Fats Waller also widened his audience by appearing regularly on WLW in Cincinnati, a radio station which at that time could be heard throughout the country. It was there, in 1932 and 1933, that he formed the band known simply as _____Fats Waller's musicianship was highly regarded, especially in Europe, where jazz was probably taken more seriously than in the United States. His overseas tours in 1938 and 1939 were triumphs, and in 1942 he gave a jazz concert at Carnegie Hall. And he never lost his love for the classics - his organ performances of Bach are legendary. The success of Fats Waller's records, movies, radio appearances and tours made him one of the first American superstars. Fats Waller was as generous as he was overindulging, and stories of his bigheartedness and high-living abound. He consumed enormous quantities of food and liquor. He bought instruments for down-and-out musicians, loaned money to friends without being asked and treated himself to a | |

|

| |

Trummy Young: a bio...

Growing up in Washington, Trummy Young was originally a trumpeter, but by the time he debuted in 1928 he had switched to trombone. Extending the range and power of his instrument, Trummy Young was a major asset to Earl Hines' orchestra during 1933-1937 and really became a major influence in jazz while with Jimmy Lunceford (1937-1943). Growing up in Washington, Trummy Young was originally a trumpeter, but by the time he debuted in 1928 he had switched to trombone. Extending the range and power of his instrument, Trummy Young was a major asset to Earl Hines' orchestra during 1933-1937 and really became a major influence in jazz while with Jimmy Lunceford (1937-1943)._____Trummy Young was a modern swing stylist with an open mind who fit in well with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie on a Clyde Hart-led session in 1945, and with Jazz at the Philharmonic. It was therefore a surprise when he joined The Louis Armstrong All-Stars in 1952 and stayed a dozen years. Trummy Young was a good foil for Louis Armstrong (most memorably on their 1954 recording of "St. Louis Blues"), but he simplified his style due to his love for the trumpeter. In 1964, Trummy Young quit the road to settle in Hawaii, occasionally emerging for jazz parties and special appearances. He died in San Jose, California on September 10th, 1984. (from Scott Yanow) | |

|

| |

OnLinerNotes - JAZZ | |

|

|

we find Louis in the twenties doing much the same as he has done since, entertaining the people with bravura performances and, according to Lil Hardin Armstrong, practicing top G's at home so as not to disappoint those who came to hear "The World's Greatest Trumpet Player".

we find Louis in the twenties doing much the same as he has done since, entertaining the people with bravura performances and, according to Lil Hardin Armstrong, practicing top G's at home so as not to disappoint those who came to hear "The World's Greatest Trumpet Player". even though it had been in the Louis Armstrong repertoire for years. And the alternative takes (or bits of takes) that we are offered in this album reinforce the impression of a happy, relaxed party rather than an extra chore squeezed into an already overcrowded schedule.

even though it had been in the Louis Armstrong repertoire for years. And the alternative takes (or bits of takes) that we are offered in this album reinforce the impression of a happy, relaxed party rather than an extra chore squeezed into an already overcrowded schedule. coped with tunes of a repetitive symmetrical structure by varying the phrasing in the most subtle way while at the same time continuing to "play that lead!". Trummy Young is at his mellowest here, reminding us that the most pervasive of his influence had always been Louis Armstrong.

coped with tunes of a repetitive symmetrical structure by varying the phrasing in the most subtle way while at the same time continuing to "play that lead!". Trummy Young is at his mellowest here, reminding us that the most pervasive of his influence had always been Louis Armstrong.

As a member of Joe "King" Oliver's band, Louis Armstrong began his lifetime of touring and recording. In 1924, he moved on to New York City to play with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra at the Roseland Ballroom. Louis Armstrong continued his touring and recording activities with Fletcher Henderson's group and also made recordings with Sidney Bechet, Ma Rainey, and Bessie Smith.

As a member of Joe "King" Oliver's band, Louis Armstrong began his lifetime of touring and recording. In 1924, he moved on to New York City to play with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra at the Roseland Ballroom. Louis Armstrong continued his touring and recording activities with Fletcher Henderson's group and also made recordings with Sidney Bechet, Ma Rainey, and Bessie Smith. He worked with big bands, playing music of an increasingly commercial nature as well as small groups that showcased his singing of popular songs. In 1942, Louis Armstrong married Lucille Wilson, a dancer at the Cotton Club where his band had a running engagement. The following year, they purchased a home in Corona, Queens, where they lived for the rest of their lives. In 1947, Louis Armstrong formed a small ensemble called the All-Stars, a group of extraordinary players whose success revitalized mainstream jazz.

He worked with big bands, playing music of an increasingly commercial nature as well as small groups that showcased his singing of popular songs. In 1942, Louis Armstrong married Lucille Wilson, a dancer at the Cotton Club where his band had a running engagement. The following year, they purchased a home in Corona, Queens, where they lived for the rest of their lives. In 1947, Louis Armstrong formed a small ensemble called the All-Stars, a group of extraordinary players whose success revitalized mainstream jazz. Rhythm, with which he achieved his greatest success. With some changes in personnel, the group appeared in three feature films - "Hooray for Love", "The King of Burlesque" and "Stormy Weather" -- and numerous short subjects.

Rhythm, with which he achieved his greatest success. With some changes in personnel, the group appeared in three feature films - "Hooray for Love", "The King of Burlesque" and "Stormy Weather" -- and numerous short subjects. $10,000 Lincoln automobile. Often, however, his alimony troubles would leave him broke and in jail, writing songs for Tin Pan Alley publishers in exchange for bail money. The party that was Fats Waller's life ended suddenly, when he died of pneumonia aboard the Santa Fe Chief in 1943. As a musician, Fats Waller raised the art of stride piano (cleverly defined in "Handful of Keys") to its highest level and in so doing became one of the originators of swing music. He was probably the greatest combination of musician and comedian that America has ever produced. As a composer, pianist and singer, he wove comedy and music together so well that his songs are as fresh and funny today as they were 50 years ago. In another time and place Fats Waller might never have become a comedian and might have been the classical artist his parents - and perhaps he himself - wanted him to be. Listening to the joy and laughter of "Ain't Misbehavin' " though, we can revel in his genius and say right along with him, "...One never knows, do one?...". (from

$10,000 Lincoln automobile. Often, however, his alimony troubles would leave him broke and in jail, writing songs for Tin Pan Alley publishers in exchange for bail money. The party that was Fats Waller's life ended suddenly, when he died of pneumonia aboard the Santa Fe Chief in 1943. As a musician, Fats Waller raised the art of stride piano (cleverly defined in "Handful of Keys") to its highest level and in so doing became one of the originators of swing music. He was probably the greatest combination of musician and comedian that America has ever produced. As a composer, pianist and singer, he wove comedy and music together so well that his songs are as fresh and funny today as they were 50 years ago. In another time and place Fats Waller might never have become a comedian and might have been the classical artist his parents - and perhaps he himself - wanted him to be. Listening to the joy and laughter of "Ain't Misbehavin' " though, we can revel in his genius and say right along with him, "...One never knows, do one?...". (from