I came across this article as I was surfing the net one day. It explains the Phenomenon most people refer to as Christian Rap.

Rappers Are Raising Their Churches' Roofs

NY Times ^ | September 13, 2004 | JOHN LELAND

Posted on 09/13/2004 7:56:18 PM PDT by neverdem

At Christ Tabernacle Church in Glendale, Queens, on a recent Friday night,

Adam Durso, the church's youth pastor, raised a microphone in exaltation. "Yo,

God is so ill," he shouted, using a hip-hop term of praise.

It was more than two hours into the weekly service, and neither the pastor

nor his congregation, a multiracial group of about 350 teenagers and

adults, was ready to quit. The D.J. played a hip-hop beat, and shouts

of praise

rose from the pews. "Come on," Mr. Durso encouraged, "tear

the roof off this place in praise to God."

Eleven years after the Rev. Calvin O. Butts III of the Abyssinian Baptist

Church in Harlem ran a steamroller over rap CD's, in what has come to

symbolize the antagonism between hip-hop and the church, the two worlds

seem to be

inching closer together. The singer R. Kelly and the rapper Mase, who

left the music business for five years to become a minister, have new

hit albums

filled with gospel messages, and one of this summer's most popular songs

was "Jesus Walks," an overtly Christian rap by Kanye West.

From the church side, a growing number of ministries are adopting both

the rhythms and the bluntness of hip-hop culture. Mr. Butts remains critical

of some rap music, but younger ministers like Mr. Durso are using its

attitudes and beats to spread the gospel. In the New York area alone,

at least 150

churches or ministries use hip-hop in some form, said Kim Stewart, a

booking agent for Christian rappers. These include many storefront churches

or

campus ministries, she said.

"

Hip-hop is the language and the cry of this generation," said Mr.

Durso, 27, who mixes guest rappers and videos with conservative evangelical

preaching in his Friday services, which are called Aftershock. The results

are part revival meeting, part Friday night out.

"

In today's terms, the apostle Paul would be living in the projects saying,

'Grace and peace to you, a'ight,' instead of 'amen,' " Mr. Durso said,

using the hip-hop contraction for all right. "Don't get stuck on the

word 'amen.' 'Amen' just meant 'I agree.' Well so does 'a'ight' to this

hip-hop culture." The sometimes bumpy rapprochement between the

church and Christian hip-hop reflects changes in both. Instead of meeting

in the

middle, each is adapting to the rougher norms of commercial rap.

Christian rappers, who once presented themselves as squeaky clean alternatives

to their secular peers, are increasingly spinning graphic tales of

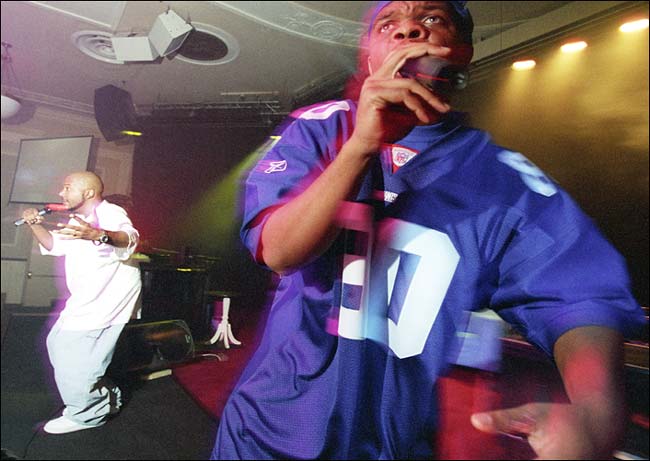

urban life, with little aroma of church sanctimony. Corey Red and Precise,

a New York duo that performed at Aftershock, rhymed about their pasts

as

drug dealers, lacing their rhymes with sexual frankness and references

to gunplay. Strutting the stage in a do-rag and football jersey, Corey

Red rapped, "I put the heat to your knot," pointing a finger

to his head like a gun, even as he talked about being saved.

For churches, making peace with hip-hop is a matter of survival, said

Ralph Watkins, who teaches African-American culture and religion at

Augusta State

University in Georgia. "Mainline churches have identified hip-hop

culture as an enemy, and that's their problem," he said. "If

you walked in to 90 percent of your mainline churches who have not embraced

this culture, you're going to find an absence of young people."

He added that even at its crudest, hip-hop flourished by telling truths

that churches ignored. "The church really doesn't want to hear the

true stories," he said. "They want the made-up stories, 'I

was broke on Thursday and God came and I got paid on Friday, ain't he

all right,

he's an on-time God.' Well, sometimes God don't come on Friday. Hip-hop

says, that's the deal. So I'll start selling weed or selling crack, because

that's the only choice I had. And that's where the church can't embrace

the honesty of what hip-hop tries to get us to understand and deal with."

In "Jesus Walks," Kanye West cites a comparable unwillingness

on the part of the rap business to address matters of faith. He rhymes, "They

say you can rap about anything except for Jesus/ That means guns, sex,

lies, videotapes/ But if I talk about God, my record won't get played,

huh?"

Mr. West, the son of a Christian marriage counselor, said that when

his father heard the song, he said, " 'Maybe you missed your calling.'

I said, 'No, maybe this is my calling.' I reach more people than any

one pastor can."

He likened "Jesus Walks" not to church teaching but to his secular

songs, which celebrate the high life without moralizing. "I don't

tell anyone they have to do this or that. I never said, 'You better have

your Louis Vuittons on or something's going happen to you.' I just

said, 'This is what I want.' Same with Jesus."

The resistance that many churches have shown to hip-hop culture resembles

previous battles over gospel music or drums in church, said Alton Pollard

III, the director of black church studies at the Candler School of

Theology at Emory University in Atlanta.

"

This is just the latest version" of the battle, he said. "It's

about the continuing need for new expressions of what it means to be

human, and the church oftentimes is not able to keep up, whether we're

talking

about jazz, the blues, soul or gospel music."

But unlike gospel and soul, "hip-hop didn't start in the church," said

Phil Jackson, a youth pastor who last year started a hip-hop ministry

called The House in one of Chicago's poorest neighborhoods.

" So there still exists some antagonism. But for this generation, the only

way to make the gospel relevant to them is through hip-hop. In my neighborhood

we don't need another church on Sunday morning. We need something to

speak to young people."

Corey Red and Precise, who call their style hardcore gospel, are emblems

of the uneasy crossover. Corey Red, whose surname is Sullivan, rejected

the church as a teenager, turning to hip-hop and small-timecrime. "I

didn't know anybody Christian my age," he said. "The ones I did

know, there was so much religiosity that we wouldn't be able to talk. That

turned me off." When he was stabbed in a street confrontation

and critically injured, he said, he felt Jesus in a way that he never

had

in church.

"

It took God to visit me outside the four walls" of the church, he

said. "That's why I love the Lord, because he came into the street

and met me where I was. Even though the people inside the four walls

wrote me off, like 'He's finished, he's not going to see 25 years old.' "

The experience put him at odds with both his secular and his Christian

peers, he said. Even now, he uses the word "religion" as a pejorative

and sees his faith as tangential to the business of churches. "I'm

not Christian by following the institutionalized religion of Christianity," he

said. "I'm Christian like what the word really means, a follower

of Christ."

He and Precise occupy a precarious niche, recording for Life Music,

a Christian label started by Derek Ferguson, the chief financial

officer of Bad Boy

Entertainment, Sean Combs's company. Bad Boy stars who rap about

sex and material excess earn instant fortunes, but Corey Red and

Precise

say they

struggle to make ends meet. Unlike Christian rock bands, Christian

rappers

are rarely played on religious radio stationsand get little support

from churches or the music industry.

Mr. Ferguson said he struggles to justify the music of some Bad

Boy acts. But their Christian alternatives, he acknowledged, can

barely

support

a small business.

"

The church has these soldiers at their disposal," said Precise, whose

real name is Robert Young. "But a lot of brothers, after a night

of risking their life, they can't even keep their lights on in their

house.

We're here for the church. But any army poorly funded is going to struggle."

At Crossover Community Church in Tampa, Fla., Tommy Kyllonen has

built a thriving ministry around hip-hop and runs an annual festival

of Christian

rap. Like Christ Tabernacle, Mr. Kyllonen's church is loosely affiliated

with the Assemblies of God denomination.

Mr. Kyllonen, 31, who raps under the name Urban D., teaches pastors

around the country to use hip-hop in their ministries. With the

success of Kanye

West, he said, churches and the music industry are looking at the

potential reach of Christian hip-hop.

But if churches simply add a D.J. or a little slang to their services,

the audience will not be fooled, he said.

"

Hip-hop is the hook that might draw them in, but what keeps them is building

a relationship with God and with other people that are here,'' he said. "Because

if they don't have that, and that doesn't become authentic, we would

just be another place to come hang out, like a club. A club gets old

after a

while. Then there's a new club that opens up down the street that the

music is better, they got a better D.J., that's where everyone's going

now. The

difference with us is that spiritual aspect."

At Aftershock, the crowd lingered long after the beats went silent.

A plexiglas's box onstage brimmed with items that people had

turned in at

previous services,

including secular CD's, pornography and gang insignia.

Leamon Richardson and Richard Dauphin, who arrived well before

the doors opened, embodied the complicated messages of holy hip-hop.

Both are rappers.

Mr. Richardson, 19, who lives in the South Bronx, called himself

a "walking

testimony," and wore a T-shirt celebrating 50 Cent, a secular

rapper who rhymes about dealing drugs and killing people.

Because of the shirt, Mr. Richardson said, "You might see me and have

a bad perception." But he added: "I don't take nothing from

50 Cent because he's not talking about anything godly. I pray for him."

Mr. Dauphin said that people who cannot understand this apparent

contradiction are blind to the prophetic powers of hip-hop. "We're street disciples," he

said. "You can be the greatest preacher in the world and not reach

the street. That's where we're at."