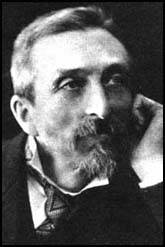

Charles Booth (1840 - 1916)

|

The village of Thringstone has a special claim to fame in its association

with the Rt Hon Charles Booth PC (1840 - 1916) of Gracedieu Manor, the great

philanthropist and pioneer of social research, whose tomb and beautiful epitaph

can be found on the north side of Saint Andrews

churchyard.

Mr Booth was a shipping line owner whose revolutionary inquiry into the

conditions of the London working class and tireless campaign for the

introduction of old age pensions helped lay the foundations of the modern

welfare state.

He was born at Liverpool on 30 March 1840, the third son of Charles Booth and

Emily Fletcher. Charles Booth Snr was a wealthy corn merchant who, in 1860,

left to each of his five children the sum of £20,000. In 1862, the young

Charles combined his fortune with that of his eldest brother Alfred, investing

it in the construction of two steamships, the Augustine and the

Jerome, with the aim of building up a fleet to carry merchandise to and

fro across the Atlantic. From this relatively modest enterprise grew the Booth

Steamship Company, a huge concern which gained interests in many parts of the

world, especially in the Amazon River trade of South America, and of which

Charles was Chairman until 1912. The construction of the great harbour of

Manaus in Brazil occurred as a result of the Booth enterprise.

In 1871, Charles married Mary Macaulay of London, one of the distinguished

Macaulay family, whose grandfather, Zachary, had been instrumental in bringing

about the abolition of slavery and whose uncle was the great historian, Lord

Thomas Babbington Macaulay.

With a station in life so far removed from the perspectives of the working

poor, one might wonder just how it was that Booth came to divert so much of his

energy and resources into the arena of social questions and, moreover, how this

giant figure came to be buried within the humble confines of Thringstone

churchyard.

Charles Booth always seems to have had an inherent concern for the welfare of

working men and as a young man he became a Radical and campaigned for the

Liberal Party in Liverpool. But he quickly became disillusioned by the fray of

local politics and found that his efforts to bring about change through these

channels were of little effect. Thereafter, Booth was never a keen partisan to

any political ideology and remained independent in his actions. However, it was

while campaigning for the Radical cause in the General Election of 1865 that

Charles made house to house visits in the Toxteth slums. Here he encountered

ignorance, poverty and squalor on a scale he had never before imagined and

which deeply shocked him.

Like many other better off Victorians, Charles had hitherto been unaware of the

terrible living conditions suffered by so many of the working class. An early

writer on the subject of poverty, Henry Mayhew, once described the poor as 'a

large body of persons of whom the public has less knowledge than the most

distant tribes of the earth'. More affluent citizens were able to ignore

poverty close to home because of the segregated 'zoning' of many British

cities, a physical distance between the poor and the better off

There were those who were anxious to play down the problem of pauperism,

fearing that an acknowledgment of such would fan the flame of revolution and

overturn the social order. Many blamed the poor themselves for their misfortune

and saw poverty as a consequence of their own fecklessness and personal

inadequacies. In any case, very little had ever been written about poverty and

with so many contradictory views being aired about the nature and extent of

poverty in England at that time, Booth sought to discover an accurate picture

of existence among the working masses of London, using statistical methods of

study.

In 1886, he launched his monumental inquiry, a survey to which he was dedicated

without intermission for the next seventeen years. The results of his

investigations were published in seventeen volumes between 1889 and 1903,

entitled "Life and Labour of the People in London".

The years of painstaking work necessary to compile this survey involved not

only Booth, but also a large body of assistants, including his wife's cousin,

Beatrice Potter (later Mrs Sydney Webb) and Mary Booth revised and corrected

it. Booth's granddaughter, Belinda Norman-Butler, estimated that the inquiry

must have incurred a personal expense to Charles well in excess of

£40,000. Called by 'The Times' the grimmest book of its generation, the

survey revealed that approximately one third of London families lived in abject

poverty, on about £1 per week or less, and a successive inquiry by Seebohm

Rowntree in York produced similar conclusions.

The efforts of Booth and Rowntree provided irrefutable evidence of the enormity

and wretchedness of poverty in England and were sufficient to end argument on

the subject. Booth believed that if given help people would improve themselves

and recommended major state intervention to this end. He saw the need for

better wages and educational opportunity as a fundamental urgency and

campaigned vigorously for the introduction of old age pensions. One of his

papers, 'Pauperism: A Picture. Endowment of Old Age: An Argument' (1891), was

based in part on studies carried out into the conditions of the poor in Ashby

de la Zouch. Charles remained undeterred in his campaign for state pensions,

despite frequent attacks of ridicule from many of his peers. One described his

proposition to be 'so Utopian that it did not provide food for serious

discussion'.

In 1904, Booth was appointed a member of the Privy Council by the Prime

Minister, Arthur Balfour, and his influence was instrumental in the passing of

the Old Age Pensions of 1908, though Booth criticised this Act for granting

pensions not to all, but only to those whose incomes fell below a certain

level. In February 1910, the Labour Party, then in its infancy, presented Booth

with an illuminated address in the House of Commons, 'To you more than any

other man' they wrote, 'this first instalment of justice to the aged is due'.

Other recognition of his work came from the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge

and Liverpool, which awarded him honorary degrees, and at Liverpool a

professorship of Social Science was subsequently established in his name.

|

The arrival of Charles and Mary Booth at Gracedieu occurred quite by chance.

The family had been living with Mary's father in London and were anxious to

find a suitable country residence, located somewhere between London and

Liverpool, where Booth's main interests lay

In the spring of 1886, Charles took his two eldest children on a short vacation

to the Midlands with the object of visiting some of the areas cathedrals and

also looking out for a potential family residence. The trip included a casual

visit to Gracedieu Manor, which was then in a rather deplorable condition, but

Charles and his children were instantly captivated by its woodland setting.

'The ground is picturesquely broken', wrote Mary Booth in 1918, 'divided into

hill and dale, covert and open space, and traversed by a winding rushing brook,

so that it affords a great variety of beauty'

Charles made an instant decision to take on the lease of the manor from the De

Lisle family, leaving to his wife the considerable task of making the place

habitable. This was to be his home until his death some thirty years later, and

up until shortly before he died his daily routine almost always included a

ramble through Gracedieu Wood

|

During the earlier years, Charles's relentless commitments to the inquiry and

to his business interests meant that he was frequently absent from Gracedieu,

sometimes for long periods, but when increased leisure time became available to

him, he became an active participant in the life of the district. The Coalville

historian, 'Lavengro', wrote, "he made the manor a focal point for the

social life of the district and became - in fact, if not in name - the Squire

of Thringstone". The village was to benefit immensely in its development

and welfare as a result of Charles and Mary Booth's constant acts of kindness

and generosity.

Examples of their charity seem too many to enumerate here, and doubtless the

Booths would have made untold other acts of personal kindness in complete

anonymity. Of their deeds, the founding of present day Community Centre

is best known, and it is hoped to put together a detailed history of the centre

in the near future. Other examples of the Booths' charity seem to have been

forgotten with the passage of time, though I would like to mention several here

on account of their particular interest.

In 1898, Charles was instrumental in the founding of the Whitwick and

Thringstone District Nursing Association, apparently in response to an outbreak

of typhoid fever in Cademan Street, Whitwick. No doubt the Whitwick Colliery

Disaster of the same year had also served as an influential factor. Mr Booth

contributed £50 annually to this organisation (of which he was president),

in addition to other donations made by Mrs Booth for special purposes, though

at the Annual General Meeting held in June 1902, the committee moved that Mr

Booth's subscription should be reduced to £10 per annum in order to

encourage the association to become self-supporting. The Coalville Times of

13th June 1902 reported that "Mr Booth considered that the request was

unique in the history of the world!".

In March 1908, it was reported that through the generosity of Mr and Mrs Booth,

a Lady District Visitor had been appointed and had taken up residence in the

vicinity. According to the late Mr Frederick Sykes (1907 - 76) of Thringstone,

who was once under groom and chauffeur at the manor, the Booths had also

provided Dr J C Burkitt of Whitwick with a motor car. Mr Sykes explained

(tongue firmly in cheek) that the car had been given because Mrs Booth's family

were "always having babies", the doctor having sped previously to the

manor on horseback!

In January 1907, Mr Charles Booth Jnr, in the absence of his father, officially

opened the Whitwick and District Gymnasium and School of Arms. This was built

by Mr Booth on Silver Street, 'to provide physical exercises combined with

drill and rifle practice for boys and young men. Mr Booth also bore the expense

of a caretaker and instructor, one Sergeant Major Turnbull RE, and in November

1909 he also provided a shooting range in an adjacent field. Members could buy

seven rounds of ammunition for a penny. The gymnasium, which later doubled up

as the Arcadia Dance Hall, was sold into private hands after the First World

War and is now divided into three private houses (numbers 6a to 6c Silver

Street).

In 1914, Mary Booth built 'The Meadows' on Loughborough Road, Thringstone.

Originally known as 'Saint Andrews' Home', this was a large white house used as

a convalescent home for women and girls from London, and run from Mrs Booth's

private income. This later became the home of Charles Booth Jnr and then a

country retreat for Lt Col Tom Booth, the eldest son, before eventually being

sold off by the family. Regrettably, as with so many local buildings of

historic and aesthetic value, this was demolished in 1989, having fallen into a

state of disrepair. It is perhaps at least some measure of consolation that a

large modern nursing home has since been built on this site and which retains

the title, "The Meadows"

Another, more enduring instigation was the founding of Gracedieu Park Cricket

Club by Charles in 1887. For many years, matches were played in the manor

grounds and Lavengro records that these were sometimes followed by 'sumptuous

feeds at the manor', which were remembered for years afterwards by local

people. The Cricket Club is now based in a field to the rear of the Bulls Head.

Sadly, Mrs Booth's one last wish of kindness to the people of the district was

denied. In January 1938 (a year before her death) she wrote to her daughter,

Meg, "Mr de Lisle has absolutely turned down my request to buy the wood

( for the benefit of the people of Leicestershire). I am very, very

disappointed". It is remembered that the Booths established primrose and

rhododendron valleys in the wood, which were tended every day by two elderly

gentlemen from Golden Row, Whitwick.

Charles Booth passed away on Thursday, 23rd November 1916 at Gracedieu aged

seventy-six years. In a lengthy obituary, the Coalville Times recorded: 'The

body, enclosed in a plain oak coffin, was removed from Gracedieu Manor on

Sunday morning and placed in the church on the chancel steps under a small

guard of the Whitwick and Thringstone Volunteer Training Corps'. Here, the body

rested for several hours prior to the service, while outside an enormous and

magnificent collection of floral tributes mounted to form 'a bank of bloom'

near the simple ivy-lined earth grave.

In her memoirs, Mary Booth wrote , Charles '...was buried in the churchyard of

the little church at Thringstone that he was accustomed to attend, and where

two of his daughters were married. Those of his relatives and friends who were

able to come quite filled the small building, and there was but little room

left for the villagers who loved him. But they assembled in the churchyard,

where altogether sang the hymn, "O God, our help" at the grave side'.

In 1920, a tablet designed by Sir Charles Nicholson was unveiled to Mr Booth's

memory in the crypt of Saint Paul's Cathedral, London. The

Reverend C Shrewsbury , Vicar of Thringstone,

accompanied members of the Booth family at the unveiling ceremony, which was

performed by Sir Austen Chamberlain, then Chancellor of the Exchequer. Booth

was a great admirer of Saint Pauls and had presented the Cathedral with a copy

of Holman Hunt's most famous painting, "The Light of the World" in

1904. The painting cost Booth £1,000, and an additional £5,000 to

send it on a world tour. Lady Holman Hunt was among the mourners at Thringstone

Church on the occasion of Charles Booth's funeral.

Mary survived her husband by more than twenty years and died on 25th September

1939 aged ninety two years. It is said that news of the outbreak of war was

kept from her. She was laid to rest with her husband and their simple, flat

white marble tombstone reads:

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

CHARLES BOOTH,

BORN AT LIVERPOOL 30 MARCH 1840,

DIED AT GRACEDIEU 23 NOVEMBER 1916.

DURING MANY YEARS, HE DEVOTED

THE LEISURE OF AN ARDUOUS LIFE

TO A STUDY OF THE CONDITION

OF THE POOR IN LONDON.

HE DILIGENTLY SOUGHT FOR

A FOUNDATION ON WHICH REMEDIES

COULD BE SECURELY BASED:

AND HE LIVED TO SEE THE

FULFILMENT OF A PART OF HIS HOPES,

IN THE LIGHTENING OF THE BURTHEN

OF OLD AGE AND POVERTY.

TO THOSE WHO LIVED UNDER

HIS IMMEDIATE INFLUENCE,

HE BROUGHT UNFAILING HELP

AND JOY : HE LEAVES THEM

A PRECIOUS EXAMPLE.

REJOICE IN THE LORD ALWAY:

AND AGAIN I SAY REJOICE. PHIL IV.4.

AND OF HIS WIFE

MARY CATHERINE

DAUGHTER OF

CHARLES ZACHARY MACAULAY,

BORN AT BRISTOL 4 NOVEMBER 1847,

DIED AT GRACEDIEU 25 SEPTEMBER 1939.

TRANSCRIPT OF CHARLES BOOTH'S MEMORIAL TABLET IN SAINT PAUL'S CATHEDRAL, LONDON

CHARLES BOOTH

MERCHANT SHIPOWNER

MEMBER OF HIS MAJESTY'S MOST

HONOURABLE PRIVY COUNCIL

BORN 1840 DIED 1916

Throughout his life having at heart

the welfare of his fellow citizens and

believing that exact knowledge of

realities is the foundation of all reform,

he devoted himself to the examination

and statement of the social, industrial

and religious condition of the people

of London. Those who knew him loved

him and drew inspiration from the

energy of his leadership and the

originality of his mind.

IN FAITH HOPE AND LOVE

THEY DEDICATE THIS TABLET TO HIS MEMORY.

EXPECTANS RESURRECTIONEM

MORTUORUM.

|

Click here for detailed photographs of Charles Booth's tomb

Above information taken from, "Saint Andrews, Thringstone: Its Fabric,

Its Ministers and Their Flock", by Stephen Neale Badcock, unpublished,

1997.

Quotes about Charles Booth...

In her diary, Beatrice Potter recorded her first impressions of Charles

Booth (9th February 1882):

It is difficult to discover the presence of any vice or even weakness in

him. Conscience, reason and dutiful affection are his greatest qualities; what

other characteristics he has are not to be observed by the ordinary friend. But

he interests me as a man who has his nature completely under his control, and

who has risen out of it, uncynical, vigorous and energetic in mind without

egotism.

Bernard Newman (1897 - 1968), British Author and Lecturer

wrote:

I remember how, as a boy, my father took me over to Gracedieu Manor to

see Charles Booth - my father was a keen Liberal. On the way he told me about

the man we were going to see. Charles Booth did not make political speeches,

but he investigated social problems scientifically - especially the conditions

under which the poor lived. We sat in his study, and he spoke soberly of his

investigations. But then a great passion took control of him as he described

what had to be done. He began to talk about Old Age Pensions - of which I had

then never heard. So great was his enthusiasm that he persuaded the politicians

to take up his idea- the beginning of the Welfare State: a modest beginning-

5s.a week.

Booth was not of Leicestershire origin, but at the time it was a Radical

county, and he settled there because he found the atmosphere congenial and

support for his ideas. I was too young to understand all he said, but the force

of his personality affected me long afterwards. "Talk is not enough,"

he said. "Action is what we need."

Pony and Trap courtesy of Chanimations