Caucasoid,

Caucasoid, The biological variety of living human populations has from the

beginnings of anthropology been approached through the study of race.

There have been several attempts to categorise the variety of present humans. Many of these are unnecessarily procrustean, but have some value in purely descriptive terms. A typical classification based on human visible variation is as follows:

Caucasoid,

Caucasoid,

from northern Europe to northern africa and India. These are depigmented to a greater or lesser degree. Hair in males is generally well developed on the face and body, and is mostly fine and wavy or straight. A narrow face and prominent narrow nose are both typical.

Negroid,

Negroid, (or Congoid), in sub-Saharan Africa. Skin pigment is dense, hair woolly, noses broad, faces generally short, lips thick, and ears are squarish and lobeless. Stature varies greatly, from pygmy to very tall (and in the latter the face is long). The most divergenet group are the Khoisan (Bushman and Hottentot) peoples of southern Africa.

Mongoloid,

Mongoloid, found in all Asia except the west and south (India), in the northern and eastern Pacific, and in the Americas. The skin is brown to light, hair coarse, straight to wavy, and sparse on the face and body. The face is broad and tends to flatness. The eyelid is covered by an internal skinfold in the central populations but such folds are less marked or absent elsewhere. The teeth often have crowns more complex than in other people, and the inner surfaces of the upper incisors frequently have a shovel appearance.

Australoid,

Australoid, the aboriginals of Australia and Melanesia. Skin is dark; hair predominantly wavy (Australia) or frizzy (Melanesia), with blondness in children (lost in adulthood) being common throughout. The head is long and narrow, the forehead sloping with prominent brow ridges, and the face has a projecting jaw.

Such descriptions of the distribution of modern human variety have been useful in the study of human evolution only as a source of hypothesis. Until about 1930 not even this was true. Human fossils were still extremely few, and some of them involved mistakes in stratigraphy or even outright fraud. Questions were not posed as to origins, which were simply accepted as somehow "given". Any apparent blurrying or distinction between "races", as perceived in variations from the supposed type of race, was explained as a mixture of some more sharply defined earlier races or types: and this is as far as the quest for an explanation for human geographic differences went, except for claims of hypothetical migrations of primordial peoples.

Now that the Pleistocene setting of human evolution is better understood and far more fossils are available we can pose hypotheses as to the origins of geographical differences in modern humans. These lie between two extremes. The first sees racial differences as already existing at the stage of Homo erectus, in populations of different regions. Skeletal distinctions among fossil populations many have persisted to the present although modern populations undoubtedly represent generally similar Homo sapiens. While not denying contact and some migration, those who hold this view of human evolution see it as essentially separate in the main areas of the world. This is known as the Multiregional Hypothesis.

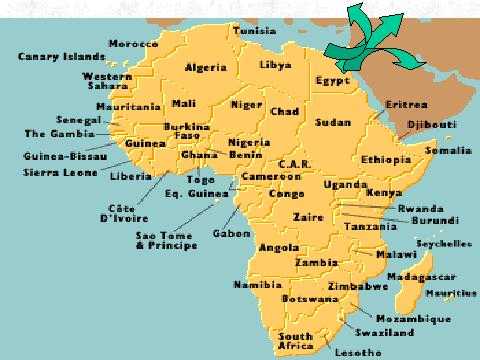

The second position is the replacement or "Out of Africa" hypothesis. This emphasises the general homogeneity of living humans and sees present populations as primarily descended from one main populations, which originated relatively recently in a single region, later migrating outwards. Other populations, possible deriving from Homo erectus although they might have contributed to some extent to different living peoples, were in the main replaced by the more modern arrivals from elsewhere. According to proponents of this view, racial differences came later, after the predominance of Homo erectus; they see humankind as genetically more homogeneous, most if not all of the earliest populations have disappeared. It is difficult to distinguish between these views solely on the basis of morphological patterns in living populations or on a preliminary assessment of distinctions among fossils.

Nowadays, the "Out of Africa" model is the most widely accepted due to the scientific results given by Allan Wilson in 1987. He concluded the theory of the "Out of Africa" hypothesis" due to the studying of mitochondrial DNA which pinpointed Africa as the country of origin of modern humans. As shown in the figure above, hominids dispersed from Africa in Europe and Asia.

Site Findings of Hominids

Site Findings of Hominids The Multiregional Hypothesis of the Origin of Modern Humans

The Multiregional Hypothesis of the Origin of Modern Humans The Out of Africa Hypothesis of the Origin of Modern Humans

The Out of Africa Hypothesis of the Origin of Modern Humans