The History and Evolution

of Road Maps

December 2005

Geography 20H Final Report

Note to the Reader: A web page format has been chosen for

this report to ensure that the graphics of maps are represented in the clearest

detail possible without compromising space for the size of a sheet of

paper. Thank you for your

understanding.

Abstract: Over time, the focus and

presentation of road maps have changed dramatically. From the 1680s through today, some items

remain important to display on the map (such as town names), but many other

features have been added or removed.

This can be proved by studying road maps from the past through the

present and analyzing the differences.

The study of road maps is important not just to people lost on highways

but also to geography at large and how Americans choose to represent our

landscape on two-dimensional surfaces.

Key

Words: highways, roads, map, history, paper, Internet, driving, design

Ever

since roads began to appear, mankind has looked for the ultimate way to

represent how its transportation system is laid out so that travelers and

observers can see large sections at once in an organized fashion. For much of human history, roads and

paths were laid out based on the shape of the land it traveled over, and often

attempted to create the shortest distance between two points of interest

(cities, etc.). If a mountain

happened to impede the quickest flow of travel, then the road was built around

it in the most convenient place.

Roads have also mirrored the growth of civilization; for each new

technological era, new ways were developed to build, maintain, and map roads.

For

this study on the history of highway maps, I will be analyzing the growth and

expansion of American roads, which is directly proportional to the growth,

expansion, and sharpening of the American road map. Over time, roads have become wider,

smoother, and safer, while maps have become more detailed, more precise, and

more interactive. Road maps still

maintain many of the same features today as when they were first produced, but

the additional information now available with an overview of the highway system

from point A to B can prove invaluable in fully understanding the American

landscape.

Beginning

with

Finding

accurate maps of roads during this time was rather difficult. First of all, the roads were never

permanent and could often change depending on floods or other events. What most people were looking for in

maps were landmarks and land ownership, as that would give the observer as much

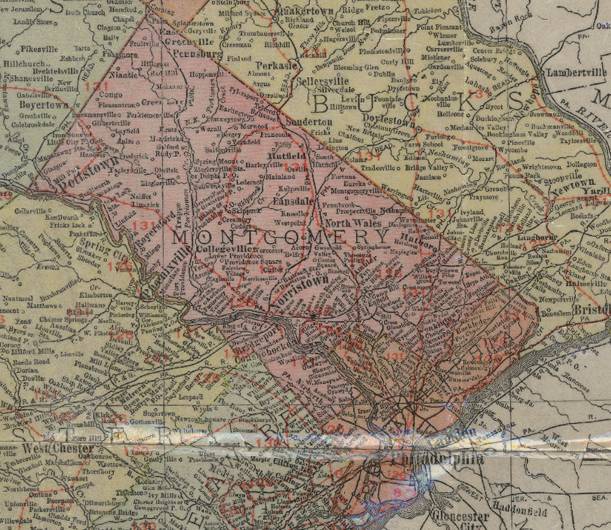

information as they needed while traveling in the largely rural colonies. The following picture shows an excerpt

of a 1687 map of the city of  [2]

[2]

In this map,

the city of  [3]

[3]

This map is a

good representation of modern-day Center City Philadelphia from over 300 years

ago. Broad Street remains as today,

with its intersection at High Street (now

Beginning in

the late 1700s and continuing through the 1800s, the paths between places

became much more important as the vast tracts of land from the 1600s were split

into towns and homesteads. This map

is from 1792, and shows a much larger area than the 1687 map, but is

approximately the area that will be displayed in the rest of the maps.  [4]

[4]

This

map is beginning to show the makings of modern southeastern

In

terms of hand-drawn detail (since the map is still hand-drawn), the city of

Philadelphia appears to have expanded considerably to the northeast and south,

Several different types of building can also be found on the map, including

churches (two can be found between West and East Marlborough in the lower-left

corner) and other landmark buildings, simply marked with black rectangles. There is not, as of yet, a standard way

of writing place names; the name for

Although

the 1792 map showed trails and paths, there were still few ways to travel

quickly between destinations, as the best ways to travel were still either on

horses or boats. This continued

throughout the 1800s, as paths were improved but the total travel time was

still rather excessive. Once the

automobile was invented and made affordable for the average American, the need

for an improvement in the transportation system became apparent. However, it would still take several

decades for the car to become

The map traces

railroad lines because of the “R. R.” designations along most of

the lines, but also because the lines connect cities directly in a way the

roads today do not do exactly. Yet

how the railroad lines were laid meant a lot to the future roads that would complement

and then overtake railroad lines as forms of transportation. For example, US Route 202 today largely

follows the line connecting Doylestown in

This map

essentially illustrates how the country was about to change with the arrival of

the automobile into average American life.

The next few decades would completely reshape the American

transportation network, but thanks to the lines laid out by the railroad

companies, roads would have a basic framework to follow as they slowly spread

out across the country. The next

few maps will demonstrate this postulate.

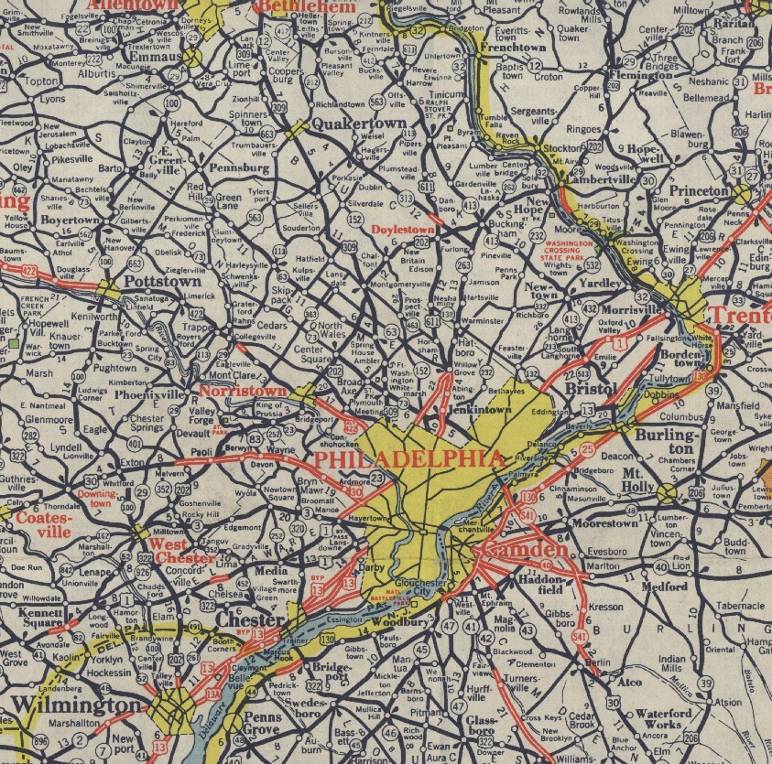

During the

1930s and 1940s, road maps became indispensable for traveling longer

distances. Maps were often put out

by oil companies, marking their own stations on the map. This map is from AAA (the American

Automobile Association) from 1947.

This is the

first of what can be called “modern highway maps.” It is clear that over the past thirty

years, massive amounts of construction and upgrading of old paths was done on

these new roads. The

Another

example of a map from this time is this map from the United States Geological

Survey in 1955. Roads have become

important enough by this time that even maps that used to be mainly topological

must now include roads to provide context for the geological features.

Interestingly,

due to the colors chosen on this map, the roads’ pinkish color appears to

overshadow the intended topological lines in brown. This is another testament to how

important roads had become to the American society and how all sorts of maps

now reflected the changing landscape.

Another interesting addition to this map is the presence of the

Pennsylvania Turnpike and Northeast Extension, running north from outside of

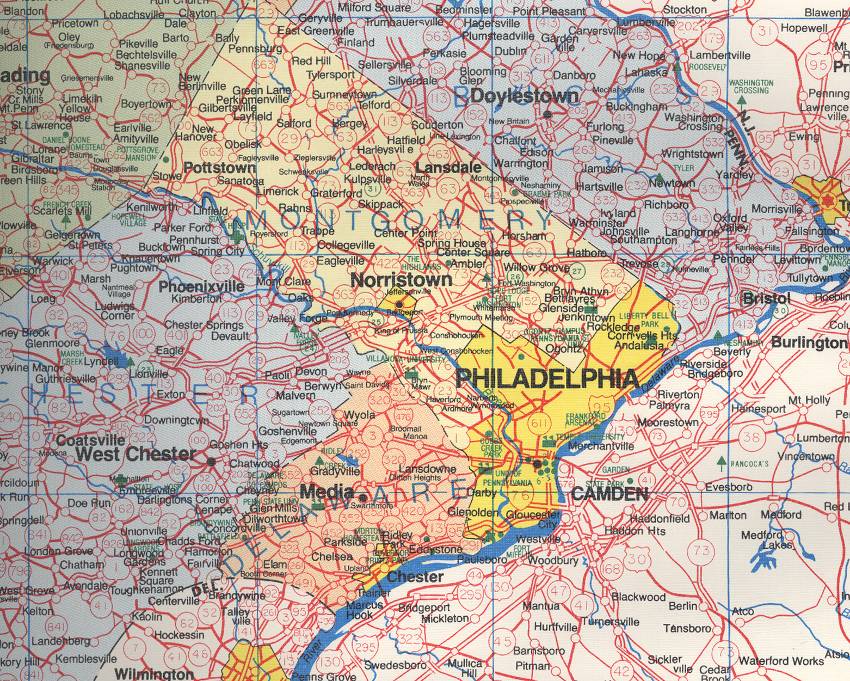

The end of the

20th century brought about the introduction of the interstate

highway system along with refinements of how maps were drawn, labeled, and

presented. The Eisenhower

Interstate Highway System was initially proposed and developed for national

defense purposes, but quickly became popular for all types of travelers. The impact of the interstate highway

system is evident from this 1975 USGS map.

This map,

while not specifically for roads, illustrates perfectly the goal of roads: to

connect major urban areas. Several

interstate highway designations have been added to this map, including I-76 and

I-95, but the actual physical roads are not very clear because they mostly run

through urban areas. These next

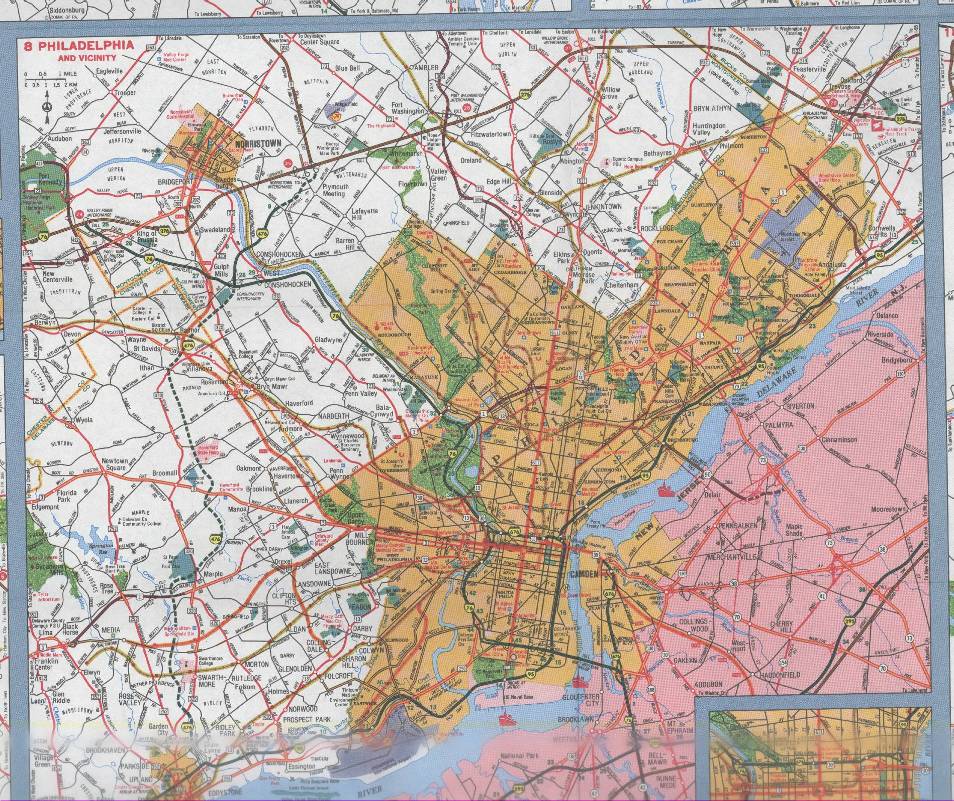

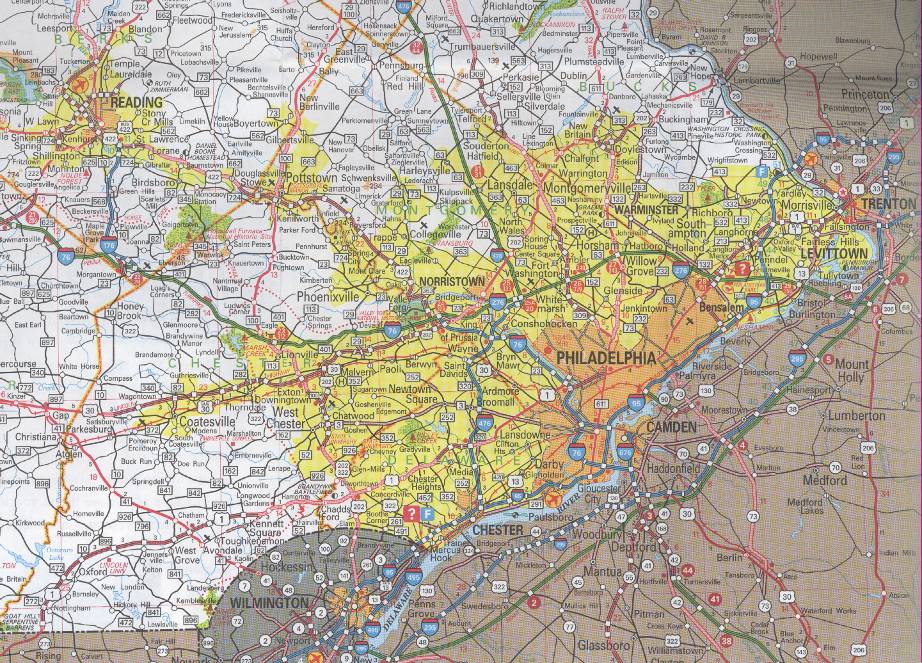

maps from the late 1980s and 1990s show the current state of paper road maps in

This Champion

Maps map from 1989 is interesting in a number of ways. Note the very large circles used to

label state routes, which can create some confusion (in particular, the

confluence of PA 252, 352, 452, and 320 outside of

The state highway

maps have finally brought clarity and order to a rather mishmashed

This

is the beginning of a reflection of the need for different levels of detail in

a certain area. The first map is

useful for larger and longer trips, while this would be more useful for travel

within the

These

next few pictures reveal ways that even within one decade (the 1990s), the art

of road map making could be improved.

First is a picture for comparison’s sake from 1991 of the USGS

topographic state map.

Besides

the different towns, cities, roads, and bodies of water, the only other marked

landmarks are the three airports in a line from Southwest Philadelphia to

Northeast Philadelphia to

Maps

around this time appeared to begin to be obviously computer generated. The PA keystone shields on top of

While

the maps still look official, there is something about the different fonts of

words and colored interstate signs that gives a more

“user-friendly” look to these two maps as opposed to previous

ones. After all, the point of maps,

ever since they were introduced, is to depict as accurately as possible how

roads interacted with the landscape, the cities they connected, and each

other. Clearly, the 2003 maps do a

good job of showing all three; interchanges such as I-476 (now complete!) and

US 1 outside of Marple west of

Over

300 years, the mapping of America transformed from hand written diagrams of

land ownership and 10 by 20 cities to an elaborate process involving space

management, color, and the real landscape as much as possible. Since transportation has changed, maps

have changed along with it. Maps

are no longer simply for people attempting to diagram the landscape, but are useful

tools in mapping the shortest distances between two points.

In

some ways, the story is done. Paper

maps are still being refined as both new graphic design techniques and new

roads appear. However, a much

larger force may soon render paper maps completely obsolete. The idea of mapping through the Internet

was born out of the wish for interactivity in mapping and directions. What if a program could compute the

fastest way between two points on the landscape using roads? Several services appeared soon after the

Internet became public knowledge offering maps and driving directions online,

such as Mapquest.

Note

the zoom function available on the left side of the map. This solves one of the oldest problems

of maps: how to get the exact amount of detail necessary for the map in

question. This eliminates the need

for maps for several specific areas as well as overview maps. Notice also how these online maps have

taken many cues from paper maps in terms of the colors of different types of

roads and road labels. This is to

ensure that someone will not feel lost using the new technology, as these

online maps are designed to look mostly like the paper ones but have many more

features.

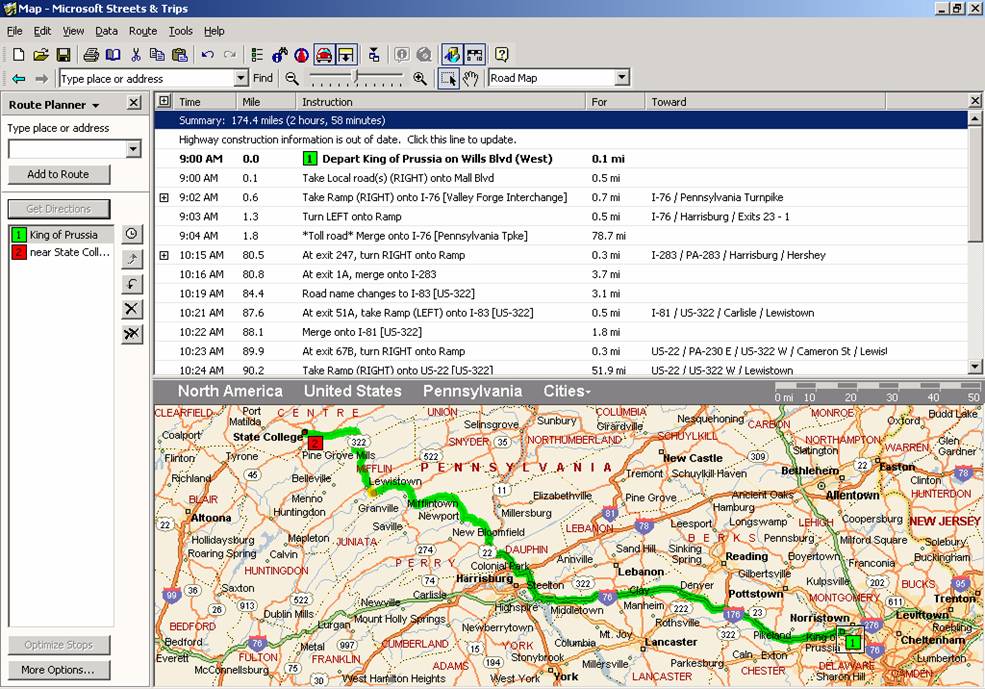

There

are also stand-alone computer programs that do not require an active Internet

connection. One of the most famous

is Microsoft Streets and Trips, which has many of the same features as online

computers. The following is a

screenshot from Streets and Trips showing a simulated trip from

Unlike

paper maps, you can “ask” a computerized map program to calculate

all sorts of details about your journey for you, including mileage, estimated

time, and even turn-by-turn directions.

Note the yellow patch around Lewistown where the computer is detecting

construction along US 322. This

would be simply impossible with any sort of paper-based map.

The

final frontier in map making is based on satellite imagery. If the roads’ exact locations do

not need to be estimated, then they exactly represent real life, one of the

goals of true map making. Several

programs have been developed to overlay map data with satellite imagery,

including Google Earth from Google, Inc.

Google

Earth can not only give exact maps of certain areas, but also driving

directions to marked places. The

technology is at times frightening, but also fascinating that this may

completely replace paper maps within a few years. For example, this is a view of my house

at a supposed “altitude” of 1000 feet.

[19] The

satellite image is so clear that you can see the car in my driveway. This final graphic is a view of State

College and the

[19] The

satellite image is so clear that you can see the car in my driveway. This final graphic is a view of State

College and the  [20]

[20]

This

technology of satellite mapping is exploding and providing the perfect base for

GIS (geographic information systems).

All sorts of overlays onto this map have already been created for public

usage, such as population and crime data.

As more and more information becomes digitized, more and more ways of

handling and analyzing the information will be needed. This is where computer-based mapping

will play a very important role.

The history of

road maps mirrors the history of vehicles.

Both started out as very crude ways to get somewhere and understand

where you will be going. Over time,

however, both improved tremendously.

Today, we have vehicles that can do nearly everything except drive

themselves and maps that can show nearly everything except live images of

traffic. I am sure that someone is

working on both of these current limitations right now, but even with

limitations, it is remarkable to trace the rapid refinement of map making. The amount of detail now present on

computerized maps makes it possibly to find nearly anything, not just the

quickest way between two points. I

know that mapping technology will continue to grow in new and unforeseen ways

as roads continue to evolve during the 21st century.

Figures:

|

Title of Map |

Call Number (if from Map

Library) |

Company/Organization |

|

|

G3820 1991.A4 |

USGS |

|

Champion Map of |

G3820 1989.C4 |

Champion Maps |

|

State of |

G3820 1975.U5 |

USGS |

|

State of |

G3820 1955.U5 |

USGS |

|

|

G3820 1911.R3 |

Rand McNally |

|

“Map of the State of |

G3820 1792.H6 (reprinted 1894) |

Reading Howell |

|

“A Map of the Improved

Part of the |

G3820 1687.H6 (reprinted 1894) |

Thomas Holmes |

|

Official Transportation and

Tourism Map |

G3821.P2 2003.P4 |

State of |

|

|

G3821.P2 1998.A4 |

Alfred B. Patton, Inc. |

|

Official Transportation and

Tourism Map |

G3821.P2 1991.A4 |

State of |

|

|

G3821.P2 1947.A6 |

AAA |

|

|

|

Mapquest |

|

|

|

Microsoft |

|

Earth |

|

Google |

|

|

|

Google |

|

|

|

Google |

References: