comments by Patrick C. Ryan (1/31/98)

Sky and Earth

engendered the cosmic deities

by maintaining a connection;

however, the Sun and Moon were regarded

as the eyes of the sky-god.

This connection was visualized in many related ways:

as a column;

as a ladder;

as a bush or vine;

as a mountain;

as a cosmic feature, i.e. the Milky Way;

and sometimes, as the male member, through which the further process of creation, conceptualized as sexual reproduction, was accomplished.

One can immediately perceive that all of these symbols but two are tubular; the second next to last, of course, conical or hemispherical, which suggests the glans penis; and which may correlate to the alternative conception of the earth as male; the next to last, roughly a long rectangle.

Could an originally female Earth during the period of man's existence as a food-gatherer have been altered in some cultures to a male Earth with the introduction of plough agriculture? We simply do not know.

The references to this component of creation, the World Tree, are so numerous and important that virtually a book could be written detailing them alone. And, in fact, it is close to the truth to characterize an interesting book written on ancient Mayan myth (Freidel, Schele, Parker 1993) as being centrally devoted to this important symbol.

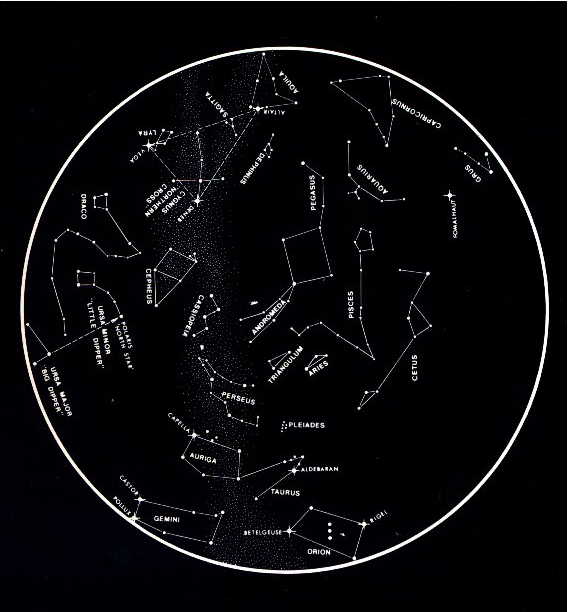

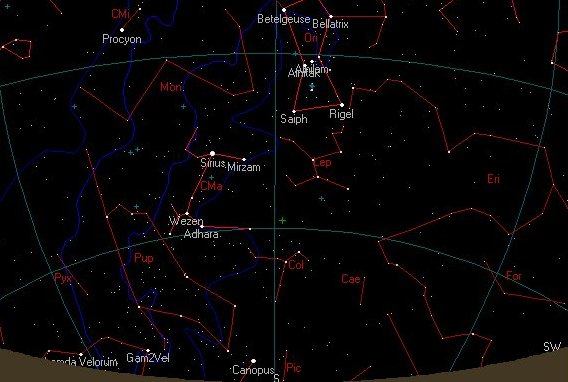

This connection is often called the axis mundi, i.e., the "axis of the earth"; and was a structure which led from the cosmic center, the North Pole, to the terrestrial center, which was usually defined in terms of a sacred place within the residential area of the culture involved though, according to the Mayan tradition as interpreted by Freidel/Schele/Parker 1993 (see p. 79; and entries under Orion on p. 536), it seems to have its southern end in the triangle formed by the two stars (Saiph and Rigel of Orion proper) and Alnitak in the Belt of Orion.

In view of this interpretation of Mayan myth, it is difficult not to want to correlate the alignments of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Gizah, which has a northern passage that pointed to Thu'ban, alpha Draconis, the northern Polestar in 2600 BPE; and southward to the most easterly star in the Belt of Orion: Alnitak, zeta Orionis [estimated altitude for Alnitak in 2600 BPE: 44°, 29'; altitude of the southern pyramid passage: 44°, 30'] (Bauval/Gilbert 1994: pp. 100-02).

In view of this interpretation of Mayan myth, it is difficult not to want to correlate the alignments of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Gizah, which has a northern passage that pointed to Thu'ban, alpha Draconis, the northern Polestar in 2600 BPE; and southward to the most easterly star in the Belt of Orion: Alnitak, zeta Orionis [estimated altitude for Alnitak in 2600 BPE: 44°, 29'; altitude of the southern pyramid passage: 44°, 30'] (Bauval/Gilbert 1994: pp. 100-02).

One term frequently applied to it on the terrestrial end is "the navel of the earth". In its simplest manifestation, it was simply the base of a support for the sky over the earth.

But, one of the significant functions of this imaginary connection was to enable travel among the three worlds — the sky, earth, and underworld — for various magical purposes. A common conception of it in this function is as a ladder or vine which may be climbed up to heaven or down to the underworld.

It appears likely that, in contrast to the later solar-inspired idea of a land of the dead in the West (the place of the setting sun), the earliest idea was a land of the hallowed dead in the North, and a corresponding land of the unhallowed dead in the South.

We are fortunate to be able to identify several different expressions of the axis mundi in Sumerian sources:

as a column = In-anna[k];

as a ladder = Dumu-zi;

as a bush or vine = Geš-tin-anna[k];

as a mountain; (not identified);

as a cosmic feature, i.e. the Milky Way = Ama-ga but also Draco the Dragon = Ama-ušum-gal-anna[k];

and sometimes, as the male member, through which the further process of creation was accomplished, for which the descriptive detail of the masculine prowess of Dumuzi(d) provide indirect allusions..

What we will find over and over again, in myths of every culture, is that an earlier (and perhaps originally bisexual/hermaphroditic) complex phenomenon, known principally by one name, has been subdivided into male and female aspects, which often appear as conjugal couples (sometimes, even just as sweethearts) — rarely, as antagonists, each retaining a subaspect of the earlier phenomenon; and that the products of the reproductive unions of these, sons and daughters, also often are only further subdivisions (with different epithets) of further subaspects of the same originally one phenomenon.

This fission of aspects (epithets) into apparently separate mythical entities cannot be illustrated better than with the Sumerian deity Dumu-zi(d).

The first element of the name of the god, Dumu-zi(d), which is usually translated as "true son", is written with a sign that has the following archaic forms (the later cuneiform is at the top):

There is even reason, on the basis of Hebrew Tamműz — apparently a loanword, to question whether the sign should be read DUMU or perhaps *TA/UMU.

Since I believe that Sumerian t represents IE dh, I tentatively assume that the better reading is *TA/UM[U] because I can, I believe, identify a number of IE cognates:

2. another meaning associated with this sign is "wild, furious"; I connect this with IE "dhe(:)u-mo- in Greek thumaíno:, "I am angry" (from 4. dheu- , "smoke, roil"); and with the archaic sign which is the second from the top, which I believe depicts a "cloud of smoke";

3. in the sense of "support" (I believe the first and last archaic signs represent a "cord knotted at both ends"), I connect them with IE dho:[u]-(mo-), "cord", which has Greek thô:mi(n)ks, "cord, rope, tie, bowstring"; this is "support(ed)" as in "being tied (to something for support)"; bearing in mind Hebrew Tamműz, this probably should be read *TAM[U]; "In some Sumerian poetry, Dumuzi is also referred to as ‘my Damu' (sic!)" (Black and Green 1992, p. 73). Damu is written with a sign that, according to some (Deimel), originally depicted a ‘bud'.

4. the second archaic sign from the top and possibly the next to the last do depict, I believe, "breasts exuding streams of milk"; and are related to IE dhe:m-, "nurse", in Latin fe:mina, "woman (i.e. "nurser")".

Since the earliest "rope" was vines, I believe the epithet *TA/UMU-ZI should be interpreted as "the vine-rope which rises", i.e. a "rope-ladder"; and is the earliest attestation of the "Jack and the Beanstalk" theme, which represents the polar axis as a medium for passing among the worlds of sky, earth, and underworld.

This line of interpretation is further suggested by the name of the sister of *Ta/umu-zi(d), Geštin-anna(k), "grape-vine of the sky". In one myth, she and her brother alternate six-month periods of residence in the underworld.

Should we consider *Ta/umu-zi(d) and Geštin-anna(k) as really only different epithets for one original deity? The fact that a goddess(!) of Kinirsha was known as Dumu-zi(d)-ab-zu should ease our reservations (Jacobsen 1970, p. 23)

Thus, I believe, the earliest myth visualized *Ta/umu-zi(d) and Geštin-anna(k) as complementary sides of the World Tree (based on Orion and Scorpio).

Can we go further and specify which of the two viewing positions of the World Tree belonged to each? I think we can.

At midnight on the longest night of the year (winter solstice), when the seasonal cycle of lengthening days begins, we can probably place the birth of *Ta/umu-zi(d) and going down into the underworld of Geštin-anna(k).

Conversely, at midnight on the shortest night of the year (summer solstice), when the seasonal cycle of lengthening days ends, we can probably place the birth of Geštin-anna(k) and going down into the underworld of *Ta/umu-zi(d).

Lending probability to this interpretation is: "Ritual lamentation for the death of Dumuzi seems to have been widespread. In Early Dynastic Lagaš the sixth month of the year was named after the festival of Dumuzi...The fourth month of the Standard Babylonian calendar was called Du'űzu or Dűzu, and Tammuz is still used in Iraqi Arabic as the name for July" (Black and Green 1992, p. 73).

This explains the universal interest in the constellations of Orion and Scorpio.

But the connections with the World Tree (and the Circumpolar Regions) do not end here.

A peculiar title associated with *Ta/umu-zi(d) is Ama-ušum-gal-anna(k); peculiar because ama means "mother"; and the full epithet means: "Mother Great Dragon of the Sky". This shows us once again that the cosmic deities — including, of course, *Ta/umu-zi(d) — originated as powers with gender undifferentiated.

And here we find a circumstance that we will meet often in our studies. In view of the connections of *Ta/umu-zi(d) with the polar axis, it will be no great leap of faith to assign this epithet to the constellation Draco, which circles the northern pole. Since Ama-ušum-gal-anna(k) is described in texts as a warrior, we can see the source of later connections of Inanna(k), yet another name for this phenomenon, with war.

(D)Ama-ga, "Mother Milk", is another odd epithet applied to *Ta/umu-zi(d) (Jacobsen 1970, p. 56); here, the reference is almost certainly to the Milky Way.

As the World Tree itself, we have Nin-giš-zida(k), "Lady of the Steadfast Tree". Although the testimony of her name is clear, in our sources, the sex of Nin-giš-zida(k) is male. This deity's name is mentioned in laments over the death of *Ta/umu-zi(d); and, in the myth of Adapa, we find *Ta/umu-zi(d) and a god Giš-zida(k), who can hardly be other than the alternate masculine(/sexless) form of Nin-giš-zida(k), guarding the gate of heaven — an application of the polar axis as a means of traveling among the worlds. In this myth, Adapa is told that he must say that he is in mourning for the two gods who have disappeared from earth: *Ta/umu-zi(d) and Giš-zida(k), who are here clearly equated. Since Giš-zida(k) is associated with the constellation Hydra, and Hydra is north of Scorpio, (Nin-)Giš-zida(k) is a likely candidate for the name applied to the World Tree after the summer solstice, when the days become shorter; and is therefore another epithet for the divinity represented by Geštin-anna(k). It will not be surprising to learn that Nin-giš-zida(k) is considered an underworld deity.

A very important part of the worship of *Ta/umu-zi(d) was his ritual marriage with In-anna(k), which is described eloquently in Treasures of Darkness (Jacobsen 1976, pp. 32-47). A strong suggestion that this is a cosmic event is provided by the detail that "they spread . . . lapis-lazui (hued) straw" on her "pure bed" (op. cit., p. 35-36) — lapis-lazuli, a blue mineral, has well-known connections with the sky. And we know when this marriage of *Ta/umu-zi(d), personified by the king, and In-anna(k) took place: it was at the New Year (op. cit., p. 38). Though we may never be able to document that the New Year for the Sumerians began at the winter solstice, it is tempting to think that this might have been a ceremony of the winter solstice, in the course of which In-anna(k) transferred her power to the king as *Ta/umu-zi(d) (through coition) to enable the lengthening of the days and the growing season to take place; and in one hymn, she says: "Verily, I will be a constant prolonger of Iddin-Dagan's (the king standing in for *Ta/umu-zi(d)) days" (op. cit., p. 38).

In addition, this union seems to specifically be directed towards enablement of the growing season since, at its prospect, the following wishes are expressed: "May there be vines under him, may there be barley under him . . . May old and new reeds grow in the canebrake under him . . . may grass(es) grow on their banks (op. cit., p. 42)".

But the fertility which *Ta/umu-zi(d) engenders is not without its price; and the cycle is completed by the "Descent of Inanna", in which In-anna(k) delivers him into the Underworld to escape from it herself, presumably at the time of his demise and departure. What this tale presumes is that In-anna(k) has been in the Underworld while *Ta/umu-zi(d) has been performing his nature-restoring function; and this hymn describes her descent (which presumably occurred shortly after her wedding) without revealing her motives: "She set her heart from highest heaven on earth's deepest ground" (op. cit., p. 55).

After being killed and trapped in the Underworld, by a ruse, she is released if only she will provide a substitute, which turns out to be her much-beloved husband: "Take this one along! Holy Inanna gave the shepherd Dumuzi into their hands (op. cit., p. 60)".

As mentioned above, Geštin-anna(k), by her entry, enables *Ta/umu-zi(d) to be released; and, it is very probable, that Geštin-anna(k) is here just another name for In-anna(k), whose motivation for going down into the Underworld is thereby explained.

Unfortunately, the well-distributed idea of the sun and moon as eyes of the sky-god cannot yet be found to be represented except in the form of the early probable representations of An, which was mentioned in Creation (3).

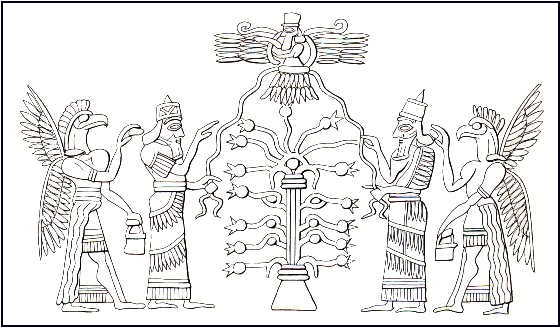

(Akkadian)

This illustration shows that the World-Tree continued to be an important part of the non-Sumerian belief system in Mesopotamia.

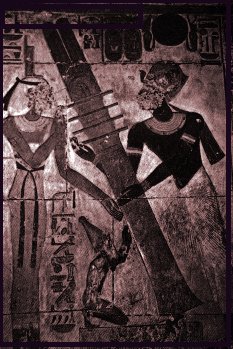

"Also, occasionally, the character of the pillar as a support is still discernible by its symbolic employment. Thus, one has the heavenly roof resting on a Djed-pillar (Pyr. 389) [author's translation from the German: Bonnet 1971, p. 150]".

The Djed-pillar was connected with Osiris, who, we shall see, was a god of the day-renewing dawn, and naturally related to the function of the Djed-pillar in renewing the natural growing cycle; and, in later tradition, was connected with Onuris (Bonnet 1971, p. 152), an apter pairing.

Onuris derives from a Greek transcription of a deity that is called Jn-Hr(.t) in Egyptian. The name can be translated simply: "Carrier of the Sky (for Face, an alternate term for the sky)". And, although Bonnet has a different idea of the original significance of the name, he does add: "Occasionally, one has him (Onuris) enter into the function of the last-mentioned (Shu, one facet of whom is the air) as a bearer of the sky and then re-interprets his name to "he who brings the sky" (author's translation: Bonnet 1971, p. 546).

Onuris is clearly an Egyptian Atlas but was identified with Ares, the Greek war-god, because, like Inanna(k), he had acquired warlike characteristics which, most likely, originally belonged to Draco (as mentioned above).

The conception of the sun and moon as eyes of the sky-god is explicitly and unambiguously present in the Egyptian belief system as mentioned above in Creation (3). This idea seems to pervade the Pyramid Texts.

to be continued on Creation (4, b)

![]()

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aston, W. G. Translator. 1956. The Nihongi. London: George Allen and Unwin

Bauval, Robert, and Gilbert, Gilbert. 1994. The Orion Mystery. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc.

Black, Jeremy and Green, Anthony. 1992. Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. Austin. University of Texas Press.

Bonnet, Hans. 1971. Reallexikon der ägyptischen Religionsgeschichte. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter

Budge, E. A. Wallis. 1969 [1904]. The Gods of the Egyptians - or Studies in Egyptian Mythology. 2 vol. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Elwin, Verrier. 1958. Myths of the North-East Frontier of India. Calcutta: Sree Saraswaty Press

English, E. Schuyler, editor-in-chief. 1948. Holy Bible. Pilgrim Edition. New York: Oxford University Press

Freidel, David, Schele, Linda, and Parker, Joy. 1993. Maya Cosmos - Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path. First Quill Edition. New York. William Morrow

Gesenius, William. (as translated by Edward Robinson). 1951 (1906). A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament — with an Appendix Containing the Biblical Aramaic. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Gottlieb, Alma. 1992. Under the Kapok Tree - Identity and Difference in Beng Thought. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press

Graves, Robert. 1959. The Greek Myths. 2 vol. New York: George Braziller, Inc.

Graves, Robert. 1959a. The White Goddess. New York: Vintage Books

Hebert, Jean. 1967. Shintô - At the fountain-head of Japan. New York: Stein and Day

Jacobsen, Thorkild. 1970. Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Jacobsen, Thorkild. 1976. The Treasures of Darkness - A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press

Laroche, Emmanuel. 1976/1977 Glossaire de la Langue Hourrite. M. E. Laroche. Revue Hittite et Asianique, Éditions Klincksieck, Tome XXXIV (A-L) and XXXV (M-Z). Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck

Leach, Maria. 1956. The Beginning. New York: Funk and Wagnalls

Piankoff, Alexandre. 1969. The Pyramid of Unas. Bollingen Series XL • 5. Princeton: Princeton University Press