|

Young and

Depressed

Ten years ago this

disease was for adults only. But as teen depression comes out of the

closet, it’s getting easier to spot—and sufferers can hope for a brighter

future

By Pat Wingert and Barbara

Kantrowitz

NEWSWEEK |

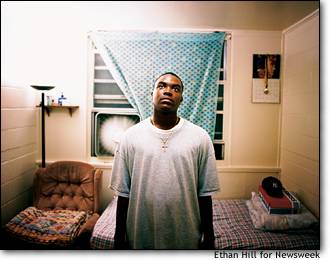

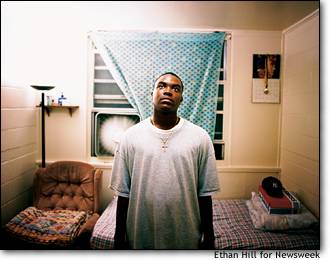

Eric Suarez,

17, who suffers from bipolar disorder, takes nine medications daily to

treat his depression-some for the symptoms and others to combat the side

effects of those drugs. Eric Suarez,

17, who suffers from bipolar disorder, takes nine medications daily to

treat his depression-some for the symptoms and others to combat the side

effects of those drugs.

|

|

Oct. 7 issue —

Brianne Camilleri had it all:

two involved parents, a caring older brother and a comfortable home near

Boston. But that didn’t stop the overwhelming sense of hopelessness that

enveloped her in ninth grade. “It was like a cloud that followed me

everywhere,” she says. “I couldn’t get away from

it.”

BRIANNE STARTED DRINKING and experimenting with drugs.

One Sunday she was caught shoplifting at a local store and her mother,

Linda, drove her home in what Brianne describes as a “piercing silence.”

With the clouds in her head so dark she believed she would never see light

again, Brianne went straight for the bathroom and swallowed every Tylenol

and Advil she could find—a total of 74 pills. She was only 14, and she

wanted to die.

BRIANNE STARTED DRINKING and experimenting with drugs.

One Sunday she was caught shoplifting at a local store and her mother,

Linda, drove her home in what Brianne describes as a “piercing silence.”

With the clouds in her head so dark she believed she would never see light

again, Brianne went straight for the bathroom and swallowed every Tylenol

and Advil she could find—a total of 74 pills. She was only 14, and she

wanted to die.

A few hours later Linda

Camilleri found her daughter vomiting all over the floor. Brianne was

rushed to the hospital, where she convinced a psychiatrist (and even

herself) that it had been a one-time impulse. The psychiatrist urged her

parents to keep the episode a secret to avoid any stigma. Brianne’s

father, Alan, shudders when he remembers that advice. “Mental illness is a

closet problem in this country, and it’s got to come out,” he says. With a

schizophrenic brother and a cousin who committed suicide, Alan thinks he

should have known better. Instead, Brianne’s cloud just got darker. After

another aborted suicide attempt a few months later, she finally ended up

at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., one of the best mental-health

facilities in the country. Now, after three years of therapy and

antidepressant medication, Brianne, 19, thinks she’s on track. A sophomore

at James Madison University in Virginia, she’s on the dean’s list, has a

boyfriend and hopes to spend a semester in Australia—a plan that makes her

mother nervous, but also proud.

AN ‘EPIDEMIC’?

Brianne is one of the lucky ones. Most of the nearly 3 million

adolescents struggling with depression never get the help they need

because of prejudice about mental illness, inadequate mental-health

resources and widespread ignorance about how emotional problems can wreck

young lives. The National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) estimates

that 8 percent of adolescents and 2 percent of children (some as young as

4) have symptoms of depression. Scientists also say that early onset of

depression in children and teenagers has become increasingly common; some

even use the word “epidemic.” No one knows whether there are actually more

depressed kids today or just greater awareness of the problem, but some

researchers think that the stress of a high divorce rate, rising academic

expectations and social pressure may be pushing more kids over the

edge. |

|

Resources

|

|

|

How to get

help |

|

|

|

This is a huge change from a decade ago, when many doctors considered

depression strictly an adult disease. Teenage irritability and

rebelliousness was “just a phase” kids would outgrow. But scientists now

believe that if this behavior is chronic, it may signal serious problems.

New brain research is also beginning to explain why teenagers may be

particularly vulnerable to mood disorders. Psychiatrists who treat

adolescents say parents should seek help if they notice a troubling change

in eating, sleeping, grades or social life that lasts more than a few

weeks. And public awareness of the need for help does seem to be

increasing. One case in point: HBO’s hit series “The Sopranos.” In a

recent episode, college student Meadow Soprano saw a therapist who

recommended antidepressants to help her work through her feelings after

the murder of her former boyfriend.

Without

treatment, depressed adolescents are at high risk for school failure,

social isolation, promiscuity, “self-medication” with drugs or alcohol,

and suicide—now the third leading cause of death among 10- to

24-year-olds. “The earlier the onset, the more people tend to fall away

developmentally from their peers,” says Dr. David Brent, professor of

child psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. “If you become depressed

at 25, chances are you’ve already completed your education and you have

more resources and coping skills. If it happens at 11, there’s still a lot

you need to learn, and you may never learn it.” Early untreated depression

also increases a youngster’s chance of developing more severe depression

as an adult as well as bipolar disease and personality disorders.

|

|

NEW APPROACHES

For

kids who do get help, like Brianne, the prognosis is increasingly hopeful.

Both antidepressant medication and cognitive-behavior therapy (talk

therapy that helps patients identify and deal with sources of stress) have

enabled many teenagers to focus on school and resume their lives. And more

effective treatment may be available in the next few years. The NIMH

recently launched a major 12-city initiative called the Treatment for

Adolescents With Depression Study to help determine which regimens—Prozac,

talk therapy or some combination—work best on 12- to 18-year-olds. Brent

is conducting another NIMH study looking at newer medications, including

Effexor and Paxil, that may help kids whose depression is resistant to

Prozac. He is trying to

identify genetic markers that indicate which patients

are likely to respond to particular drugs. |

Jonathan Haynes was diagnosed

with depression while in jail for dealing drugs. Now 18, he works as a

cook and lives with his family on San Antonio’s East Side |

|

Doctors hope that the new

research will ultimately result in specific guidelines for adolescents,

since there’s not much evidence about the effects of the long-term use of

these medications on developing brains. Most antidepressants are not

approved by the FDA for children under 18, although doctors routinely

prescribe these medications to their young patients. (This practice,

called “off-label” use, is not uncommon for many illnesses.) Many of the

drugs being tested—like Prozac and Paxil—are known as SSRIs, or selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors. They regulate how the brain uses the

neurotransmitter serotonin, which has been connected to mood

disorders.

|

|

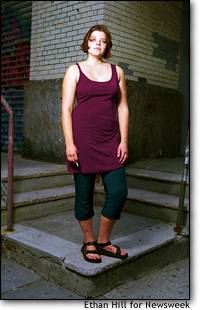

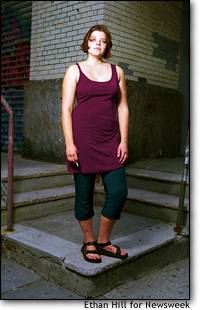

Gabrielle Cryan, now 19, got

her first Prozac prescription when she was a high school

senior

|

TRIAL-AND-ERROR THERAPY

Many depressed adolescents have a long history of trouble, which

often includes misdiagnosis and a lot of trial-and-error therapy that can

aggravate the social and emotional problems caused by the depression.

Morgan Willenbring, 17, of St. Paul, Minn., has suffered from depression

since he was 8, but school officials first thought he had

attention-deficit disorder. “I think that’s because they see that a lot,”

says his mother, Kate Meyers. “They tend to lump together what they see as

acting-out behavior.” It took more than two years to figure out a good

treatment regimen. Desipramine, one of the older antidepressants, didn’t

work. Then Willenbring spent six years on Wellbutrin, which was effective

but problematical because he needed to take it three times a day. “It’s

very easy to forget, which was not helping,” he says. When he missed too

many doses, he had trouble concentrating and got into fights at home. But

a month ago he switched to a once-a-day drug called Celexa and says he’s

doing better. He even managed to get through breaking up with his longtime

girlfriend without missing a day of school. |

|

The results of the NIMH

study may help make life easier for youngsters like Willenbring. The lead

researcher, Dr. John March, a professor of child psychiatry at Duke

University, says there is already evidence from other studies supporting

short-term behavioral therapy and drugs like Prozac and Paxil. But that

regimen works only in about 60 percent of cases, and almost half of those

patients relapse within a year of stopping treatment. “We’re hoping [the

study] will tell us which treatment is best for each set of symptoms,”

March says, “and whether the severity of symptoms biases you toward one

treatment or another.”

Until the results of

that study and others are in, parents and teenagers have to weigh the risk

of medication against the very real dangers of ignoring the illness. A

recent report from the Centers for Disease Control found that 19 percent

of high-school students had suicidal thoughts and more than 2 million of

them actually began planning to take their own lives. One of them was

Gabrielle Cryan. In 1999, during her junior year at a New York City high

school, “I obsessed about death,” she says. “I talked about it with

everyone.” With her parents’ help, she found a therapist just before the

start of her senior year who “put a name to what I’d been feeling,” says

Cryan. “My therapist made me realize it, face it and get over it.” She

also received a prescription for Prozac. Although she had some hesitations

about Prozac, “it really did help me,” she says. So did the talk therapy.

“The first part of the healing process—and I know this sounds corny—was

becoming more self-aware,” she says. The therapy helped her see that

“everything was not a black-and-white situation.” Before therapy, little

things would throw her into a funk. “I couldn’t find my shoe and the whole

week was ruined,” she says now with a laugh. “They taught me to get some

perspective.” And while her depression now is “nonexistent,” she knows

that she may have to face it again in the future. “We’re all a work in

progress,” Cryan says. “But I’ve picked up a lot of tools. When I feel

symptoms coming on, I can reach out and help myself now.” Stories like

hers are the successes that lead others out of the darkness.

With Brian Braiker in Boston, Karen Springen in

Chicago and Ellise Pierce in Dallas

© 2002 Newsweek, Inc.

|

|

|

|

Eric Suarez,

17, who suffers from bipolar disorder, takes nine medications daily to

treat his depression-some for the symptoms and others to combat the side

effects of those drugs.

Eric Suarez,

17, who suffers from bipolar disorder, takes nine medications daily to

treat his depression-some for the symptoms and others to combat the side

effects of those drugs.  BRIANNE STARTED DRINKING and experimenting with drugs.

One Sunday she was caught shoplifting at a local store and her mother,

Linda, drove her home in what Brianne describes as a “piercing silence.”

With the clouds in her head so dark she believed she would never see light

again, Brianne went straight for the bathroom and swallowed every Tylenol

and Advil she could find—a total of 74 pills. She was only 14, and she

wanted to die.

BRIANNE STARTED DRINKING and experimenting with drugs.

One Sunday she was caught shoplifting at a local store and her mother,

Linda, drove her home in what Brianne describes as a “piercing silence.”

With the clouds in her head so dark she believed she would never see light

again, Brianne went straight for the bathroom and swallowed every Tylenol

and Advil she could find—a total of 74 pills. She was only 14, and she

wanted to die.