|

This is a reproduction of a sequence of posts I had made on

the USENET groups circa November 1991. I did not want to lose

the wonderful biography, so am storing it here for posterity.

The following biography of Ghalib is reproduced from the book:

GHAZALS OF GHALIB, VERIONS FROM THE URDU BY AIJAZ AHMAD et al.

Publisher: Columbia Univ Press, 1971 (Out of print.)

|

|

|

|

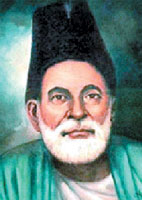

Mirza Asadullah Beg Khan -- known to posterity as Ghalib, a

`nom de plume' he adopted in the tradition of all clasical Urdu poets,

was born in the city of Agra, of parents with Turkish aristocratic

ancestry, probably on December 27th, 1797. As to the precise date,

Imtiyaz Ali Arshi has conjectured, on the basis of Ghalib's horoscope,

that the poet might have been born a month later, in January 1798.

Both his father and uncle died while he was still young, and

he spent a good part of his early boyhood with his mother's family.

This, of course, began a psychology of ambivalences for him. On the

one hand, he grew up relatively free of any oppressive dominance by

adult, male-dominant figures. This, it seems to me, accounts for at

least some of the independent spirit he showed from very early child-

hood. On the other hand, this placed him in the humiliating situation

of being socially and economically dependent on maternal grandparents,

giving him, one can surmise, a sense that whatever worldly goods he

received were a matter of charity and not legitimately his. His pre-

occupation in later life with finding secure, legitimate, and

comfortable means of livelihood can be perhaps at least partially

understood in terms of this early uncertainity.

The question of Ghalib's early education has often confused

Urdu scholars. Although any record of his formal education that might

exist is extremely scanty, it is also true that Ghalib's circle of

friends in Delhi included some of the most eminent minds of his time.

There is, finally, irrevocably, the evidence of his writings, in verse

as well as in prose, which are distinguished not only by creative

excellence but also by the great knowledge of philosophy, ethics,

theology, classical literature, grammar, and history that they reflect.

I think it is reasonable to believe that Mulla Abdussamad Harmuzd

-- the man who was supposedly Ghalib's tutor, whom Ghalib mentions at

times with great affection and respect, but whose very existence he

denies -- was, in fact, a real person and an actual tutor of Ghalib

when Ghalib was a young boy in Agra. Harmuzd was a Zoroastrian from

Iran, converted to Islam, and a devoted scholar of literature,

language, and religions. He lived in anonymity in Agra while tutoring

Ghalib, among others.

|

|

In or around 1810, two events of great importance occured in

Ghalib's life: he was married to a well-to-do, educated family of

nobles, and he left for Delhi. One must remember that Ghalib was only

thirteen at the time. It is impossible to say when Ghalib started

writing poetry. Perhaps it was as early as his seventh or eight years.

On the other hand, there is evidence that most of what we know as his

complete works were substantially completed by 1816, when he was 19

years old, and six years after he first came to Delhi. We are obviously

dealing with a man whose maturation was both early and rapid. We can

safely conjecture that the migration from Agra, which had once been a

capital but was now one of the many important but declining cities, to

Delhi, its grandeur kept intact by the existence of the moghul court,

was an important event in the life of this thirteen year old, newly

married poet who desparately needed material security, who was

beginning to take his career in letters seriously, and who was soon to

be recognized as a genius, if not by the court, at least some of his

most important comtemporaries. As for the marriage, in the predomin-

antly male-oriented society of Muslim India no one could expect Ghalib

to take that event terribly seriously, and he didn't. The period did,

however mark the beginnings of concern with material advancement that

was to obsess him for the rest of his life.

In Delhi Ghalib lived a life of comfort, though he did not

find immediate or great success. He wrote first in a style at once

detached, obscure , and pedantic, but soon thereafter he adopted the

fastidious, personal, complexly moral idiom which we now know as his

mature style. It is astonishing that he should have gone from sheer

precocity to the extremes of verbal ingenuity and obscurity, to a

style which, next to Meer's, is the most important and comprehensive

styles of the ghazal in the Urdu language before he was even twenty.

The course of his life from 1821 onward is easier to trace.

His interest began to shift decisively away from Urdu poetry to Persian

during the 1820's, and he soon abandoned writing in Urdu almost

altogether, except whenever a new edition of his works was forthcoming

and he was inclined to make changes, deletions, or additions to his

already existing opus. This remained the pattern of his work until

1847, the year in which he gained direct access to the Moghul court.

I think it is safe to say that throughout these years Ghalib was mainly

occupied with the composition of the Persian verse, with the

preparation of occasional editions of his Urdu works which remained

essentially the same in content, and with various intricate and

exhausting proceedings undertaken with a view to improving his financial

situation, these last consisting mainly of petitions to patrons and

government, including the British. Although very different in style

and procedure, Ghalib's obsession with material means, and the

accompanying sense of personal insecurity which seems to threaten the

very basis of selfhood, reminds one of Bauldeaire. There is, through

the years, the same self-absorption, the same overpowering sense of

terror which comes from the necessities of one's own creativity and

intelligence, the same illusion -- never really believed viscerrally

-- that if one could be released from need one could perhaps become

a better artist. There is same flood of complaints, and finally the

same triumph of a self which is at once morbid, elegant, highly

creative, and almost doomed to realize the terms not only of its

desperation but also its distinction.

Ghalib was never really a part of the court except in its very

last years, and even then with ambivalence on both sides . There was

no love lost between Ghalib himself and Zauq, the king's tutor in the

writing of poetry; and if their mutual dislike was not often openly

expressed, it was a matter of prudence only. There is reason to believe

that Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Moghul king, and himself a poet of

considerable merit, did not much care for Ghalib's style of poetry or

life. There is also reason to believe that Ghalib not only regarded

his own necessary subservient conduct in relation to the king as

humiliating but he also considered the Moghul court as a redundant

institution. Nor was he well-known for admiring the king's verses.

However, after Zauq's death Ghalib did gain an appiontment as the

king's advisor on matters of versifiaction. He was also appointed,

by royal order, to write the official history of the Moghul dynasty, a

project which was to be titled "Partavistan" and to fill two volumes.

The one volume "Mehr-e-NeemRoz", which Ghalib completed is an

indifferent work, and the second volume was never completed, supposedly

because of the great disturbances caused by the Revolt of 1857 and the

consequent termination of the Moghul rule. Possibly Ghalib's own lack

of interest in the later Moghul kings had something to do with it.

|

|

The only favouarble result of his connection with the court

between 1847 and 1857 was that he resumed writing in Urdu with a frequency

not experienced since the early 1820's. Many of these new poems are not

panegyrics, or occasional verses to celebrate this or that. He did,

however, write many ghazals which are of the same excellence and temper

as his arly great work. Infact, it is astonishing that a man who had more or

less given up writing in Urdu thirty years before should, in a totally

different time and circumstance, produce work that is, on the whole,

neither worse nor better than his earlier work. One wonders just how many

great poems were permanently lost to Urdu when Ghalib chose to turn to

Persian instead.

In its material dimensions, Ghalib's life never really took root

and remained always curiously unfinished. In a society where almost

everybody seems to have a house of his own, Ghalib never had one and always

rented one or accepted the use of one from a patron. He never had books of

his own, usually reading borrowed ones. He had no children; the ones he

had died in infancy, and he later adopted the two children of Arif, his

wife's nephew who died young in 1852. Ghalib's one wish, perhaps as strong

as the wish to be a great poet, that he should have a regular, secure

income, never materialized. His brother Yusuf, went mad in 1826, and died,

still mad, in that year of all misfortunes, 1857. His relations with his

wife were, at best, tentative, obscure and indifferent. Given the social

structure of mid-nineteenth-century Muslim India, it is, of course,

inconceivable that *any* marriage could have even begun to satisfy the

moral and intellectual intensities that Ghalib required from his

relationships; given that social order, however, he could not conceive

that his marriage could serve that function. And one has to confront the

fact that the child never die who, deprived of the security of having a

father in a male-oriented society, had had looked for material but also

moral certainities -- not certitudes, but certainities, something that he

can stake his life on. So, when reading his poetry it must be remembered

that it is the poetry of more than usually vulnerable existence.

It is difficult to say precisely what Ghalib's attitude was toward

the British conquest of India. The evidence is not only contradictory but

also incomplete. First of all, one has to realize that nationalism as we

know it today was simply non-existent in nineteenth-century India. Second --

one has to remmber -- no matter how offensive it is to some -- that even

prior to the British, India had a long history of invaders who created

empires which were eventually considered legitimate. The Moghuls themselves

were such invaders. Given these two facts, it would be unreasonable to

expect Ghalib to have a clear ideological response to the British invasion.

There is also evidence, quite clearly deducible from his letters, that

Ghalib was aware, on the one hand, of the redundancy, the intrigues, the

sheer poverty of sophistication and intellectual potential, and the lack of

humane responses from the Moghul court, and, on the other, of the powers of

rationalism and scientific progress of the West.

Ghalib had many attitudes toward the British, most of them

complicated and quite contradictory. His diary of 1857, the "Dast-Ambooh" is

a pro-British document, criticizing the British here and there for

excessively harsh rule but expressing, on the whole, horror at the tactics

of the resistance forces. His letters, however, are some of the most

graphic and vivid accounts of British violence that we possess. We also know

that "Dast-Ambooh" was always meant to be a document that Ghalib would make

public, not only to the Indian Press but specifically to the British

authorities. And he even wanted to send a copy of it to Queen Victoria. His

letters, are to the contrary, written to people he trusted very much, people

who were his friends and would not divulge their contents to the British

authorities. As Imtiyaz Ali Arshi has shown (at least to my satisfaction),

whenever Ghalib feared the the intimate, anti-British contents of his

letters might not remain private, he requested their destruction, as he did

in th case of the Nawab of Rampur. I think it is reasonable to conjecture

that the diary, the "Dast-Ambooh", is a document put together by a

frightened man who was looking for avenues of safety and forging versions of

his own experience in order to please his oppressors, whereas the letters,

those private documents of one-to-one intimacy, are more real in the

expression of what Ghalib was in fact feeling at the time. And what he was

feeling, according to the letters, was horror at the wholesale violence

practised by the British.

Yet, matters are not so simple as that either. We cannot explain

things away in terms of altogether honest letters and an altogether

dishonest diary. Human and intellectual responses are more complex. The

fact that Ghalib, like many other Indians at the time, admired British, and

therfore Western, rationalism as expressed in constitutional law, city

planning and more. His trip to Calcutta (1828-29) had done much to convince

him of the immediate values of Western pragmatism. This immensely curious

and human man from the narrow streets of a decaying Delhi, had suddenly been

flung into the broad, well-planned avenues of 1828 Calcutta -- from the

aging Moghul capital to the new, prosperous and clean capital of the rising

British power, and , given the precociousness of his mind, he had not only

walked on clean streets, but had also asked the fundamental questions about

the sort of mind that planned that sort of city. In short, he was impressed

by much that was British.

|

|

In Calcutta he saw cleanliness, good city planning, prosperity.

He was fascinated by the quality of the Western mind which was rational

and could conceive of constitutional government, republicanism,

skepticism. The Western mind was attractive particularly to one who,

although fully imbued with his feudal and Muslim background, was also

attracted by wider intelligence like the one that Western scientific thought

offered: good rationalism promised to be good government. The sense that

this very rationalism, the very mind that had planned the first modern

city in India, was also in the service of a brutral and brutalizing

mercantile ethic which was to produce not a humane society but an empire,

began to come to Ghalib only when the onslaught of 1857 caught up with the

Delhi of his own friends. Whatever admiration he had ever felt for the

British was seriously brought into question by the events of that year, more

particularly by the mercilessness og the British in their dealings with

those who participated in or sympathized with the Revolt. This is no place

to go into the details of the massacre; I will refer here only to the recent

researches of Dr. Ashraf (Ashraf, K.M., "Ghalib & The Revolt of 1857", in

Rebellion 1857, ed., P.C. Joshi, 1957), in India, which prove that at least

27,000 persons were hanged during the summer of that one year, and Ghalib

witnessed it all. It was obviously impossible for him to reconcile this

conduct with whatever humanity and progressive ideals he had ever

expected the Briish to have possessed. His letters tell of his terrible

dissatisfaction.

Ghalib's ambivalence toward the British possibly represents a

characteristic dilemma of the Indian --- indeed, the Asian -- peoples.

Whereas they are fascinated by the liberalism of the Western mind and

virtually seduced by the possibility that Western science and technology

might be the answer to poverty and other problems of their material

existence, they feel a very deep repugnance for forms and intensities of

violence which are also peculiarly Western. Ghalib was probably not as

fully aware of his dileema as the intellectuals of today might be; to assign

such awareness to a mid-nineteenth-century mind would be to violate it by

denying the very terms -- which means limitations --, as well -- of its

existence. His bewilderment at the extent of the destruction caused by the

very people of whose humanity he had been convinced can , however, be

understood in terms of this basic ambivalence.

The years between 1857 and 1869 were neither happy nor very eventful

ones for Ghalib. During the revolt itself, Ghalib remained pretty much

confined to his house, undoubtedly frightened by the wholesale masacres in

the city. Many of his friends were hanged, deprived of their fortunes,

exiled from the city, or detained in jails. By October 1858, he had

completed his diary of the Revolt, the "Dast-Ambooh", published it, and

presented copies of it to the British authorities, mainly with the purpose

of proving that he had not supported the insurrections. Although his life

and immediate possesions were spared, little value was attached to his

writings; he was flatly told that he was still suspected of having had

loyalties toward the Moghul king. During the ensuing years, his main source

of income continued to be the stipend he got from the Nawab of Rampur.

"Ud-i-Hindi", the first collection of his letters, was published in October

1868. Ghalib died a few months later, on February 15th, 1869.

|

|

|