Jean Moulin Main Page

MISSION IMPOSSIBLE

General De Gaulle

Mission Rex

National Council of Resistance

The Gravedigger of the Resistance

General De Gaulle

One of the best known secrets of the Second World War is the rancorous relationship among the leaders of Western allies - WINSTON CHURCHILL, Charles de Gaulle, and FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT. (Perhaps this is one of reasons for subsequent rocky relationship between the so-called allies, the United State and France.)

One of the best known secrets of the Second World War is the rancorous relationship among the leaders of Western allies - WINSTON CHURCHILL, Charles de Gaulle, and FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT. (Perhaps this is one of reasons for subsequent rocky relationship between the so-called allies, the United State and France.)

On June 17, when Marshal Pétain sought an armistice with Hitler, de Gaulle escaped to London. Next day from BBC studio, de Gaulle called on the French outside France to refuse to surrender:

The leaders who have for many years been at the head of the armed forces of France . . . have asked the enemy for a ceasefire. It's true that we have been overrun . . . but has the last word been spoken? Is all hope gone? Is our defeat an accomplished fact? Of course not! . . . France has not lost . . . We are not alone. France has a vast empire behind her. We can unite with the British Empire, that rules the sea and fights on . . [and we] can ount on the immense industrial power of the United States . . . This war is a world war . . . I, General de Gaulle, now in London, invite the officers and soldiers of France who are now or who will soon be in London, with or without their arms, to contact me . . .

Churchill recognized de Gaulle as the leader of all the Free Frenchmen, "wherever they may be, who rally to him in support of the allied cause". Free France came into being. [2]

But soon enough, Churchill often lost patience with de Gaulle's hypersensitive and morbidly suspicious behavior. The delay in Moulin's transfer to England was probably due to low priority given to Free French business, coinciding with Churchill's displeasure with de Gaulle at the time.

For instance, de Gaulle insisted that all British operations in France should go through him, an impossible position for the British. In one of worse moments, de Gaulle accused the British prime minister of dealing secretly with Hitler. Churchill wondered whether he had gone mad.

Still Churchill understood de Gaulle's haughty and often infuriating attitude.

"He had to be rude to the British", he said, "to prove to French eyes that he was not a British puppet." He added wearily, "he certainly carried out this policy with perseverance. [5]

Free France or Vichy France?

But as for Roosevelt, he just could not stand de Gaulle. He wrote to Churchill: "I am fed up with de Gaulle, there is no possibility of working with him. We must divorce ourselves from de Gaulle because he has proven unreliable, uncooperative and disloyal to both our governments." [16]

The Americans were particularly suspicious that this general with 'Joan of Arc' complex was a dictator in training. But most of all, Roosevelt wanted to make a deal with the fascist Vichy to turn her against Nazi Germany. The U.S. recognized Vichy, and Roosevelt persisted in his misguided cultivation with the anti-Semitic Vichy regime despite its continued collaborate with Nazi Germany. De Gaulle had no place in the American plan.

The crux of this problem lay at France's unique situation as the only country to sign an armistice with Nazi Germany. Unlike other governments in exile, de Gaulle's Free French was not a legitimate government elected by its people.

With no legitimacy nor territory and only thousands of soldiers under his command, de Gaulle and his Free French were utterly dependent on the British for budget, materiel, and in fact its survival. De Gaulle's coterie and thin ranks were not inspiring either. PIERRE BROSSOLETTE, a prominent socialist intellectual and journalist who joined Free France, described it as "unrelieved mediocrity". [2]

Had he wanted, Moulin the former republican prefect might have been able to set himself up in opposition to de Gaulle and try to wrest control of the Free French movement from him. [6]

Honneur et Patrie

André Dewavrin, also known as Colonel Passy

Toward the end of November, Moulin was finally ushered in to meet General de Gaulle.

Their partnership was in a way most unexpected. General de Gaulle was a right-wing Catholic army officer, who was a nationalist rather than a republican by reputation. Moulin was an anti-clerical republican, a man of the Popular Front. They could not be any more different from each another. The only thing they had in common was that each was the son of a school teacher. And they were both shy, proud, and profoundly patriotic. [2]

Although the gaullists like to claim that Moulin rallied to their cause from the very first moment, it is by no means certain that this was the case. Moulin had reasons to be suspicious of the general and his coterie.

De Gaulle's favorite army slogan of "Honneur et patrie"(Honor and fatherland) must have sounded to Moulin a lot more like Vichy's "Travail, familie, patrie" than Republic's "Liberté, égalité, fraternité".

His intelligence chief ANDRÉ DEWAVRIN, better known by his nom de guerre COLONEL PASSY, was rumored to be a member of a fascist terrorist group called Cagoule though he himself had always denied it. Pierre Cot, Moulin's mentor who exiled to the United States, believed that de Gaulle was a fascist.

Even after committing himself to the gaullist cause, Moulin retained some reservations. He wrote to Cot that "for the moment one should support de Gaulle, later we will see." And when he returned to France, he said to a left-wing resistance leader Francçois de Menthenon, "He's a very great man...But what are his real feelings about the Republic? I could not tell you. I know his official position, but...is he actually a democrat?" [2]

Nevertheless, Moulin could trust General de Gaulle to restore the democratic republic after the liberation just as de Gaulle placed complete trust in Moulin to unify resistance groups under his name.

This was possible partly because Moulin fell under a spell of De Gaulle's personality despite latter's legendary reputation for coldness. Moulin later told a colleague in France that he had been so moved that he had found himself speaking in his long-forgotten Provencal accent. He was also struck by de Gaulle's transparent love for France. [2]

As for de Gaulle, he described Moulin as being "filled to the depths of his soul with the love of France". He later wrote that Moulin was a man extraordinarily suited for the work he was to undertake: "Full of judgment and seeing things and people as they were, he would be watching each step as he walked along a road that was undermined by adversaries' traps and encumbered by obstacles raised by friends." [9]

One can also imagine that Moulin saw in General de Gaulle as the only altenrative to the Allied occupation or the Communist insurrection in postwar France. It was perhaps what infuriated Churchill and Roosevelt so much that encouraged Moulin, the fact that de Gaulle would not hesistate to stand up to his all-powerful allies. It is also worth noting that de Gaulle began to invoke "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" in his BBC speeches soon after his meeting with Moulin.

When a resistance leader Jean-Pierre Lévy frankly told Moulin that the Free French movment in London seemed to be oriented toward military goals only and that made him uneasy, Moulin personally assured him of de Gaulle's commitment to democracy and the Rupublic, saying that he would not have come back to France as de Gaulle's representative if he had thought otherwise. [4]

Mission Rex

General de Gaulle decided to send Moulin as his personal envoy and the delegate of the French National Committee to the southern zone of France with mission of organizing, coordinating, and controlling a Resistance High Command loyal to de Gaulle and willing to accept orders from London.

According to order signed by de Gaulle on November 3, 1941, his mission was to extricate the serious workers from the mere talkers in the sound resistance movements and get them sequestered into wholly separate cells, each numbering about seven men. Each cell should have a leader and a deputy leader; no cell should know its neighbor; only the leader should know the next higher contact up the chain of command; The cells' primary duty was to exist: to be the nucleus of a secret army that should rise when the allies came.

This was in itself a substantial triumph for Moulin, who could persuade de Gaulle to see the importance of the internal Resistance. It was in fact less than a week ago when Colonal Passy, the head of Gaullist intelligence office, Central Bureau of Information and Action (BCRA) told a SOE agent that "General de G. was inclined to favor propaganda to the exclusion of action, and in fact that the General appeared to have little faith in the possibilities either of a secret army or of effective work by paramilitary forces." [5]

The mission was by no means a simple task. The resistance leaders had created their movements by themselves without any help from London. They were proud and independent men, living dangerously under the Nazis, and could not be expected to follow orders as soldiers would in a traditional army command structure.

Moulin would need all the skills and experience of twenty plus years he gained in the jungle of French administration.

As the official historian of SOE puts it, Moulin, known in France as Max, carried in SOE the appropriate code-name of Rex, for it was he more than any other man - even more than de Gaulle himself - who welded the antagonistic fragments of resistance in France into one more or less cohrent and disciplined body. [5]

Making of A Secret Agent

Moulin received a crash course in the art of espionage and parachuting.

At the parachute school, he underwent a violent session of physcial training designed for men who were twenty youngers than he was. According to Colonel Passy, who joined Moulin at the parachute school, one of general physical trainings, was "flying angels", in which one must jump from a springboard over a wooden horse, without an instructor to catch him. "There is nothing like leaping headfirst over a barrier four and a half feet high if you have spent the previous year behind a desk," wrote Passy. " . . . A few hours of this and we had been reduced to the state of crippled old men. After two days, when we were just about at the pre-coma level, they said we were fit to jump."

Passy noticed that after one of the sessions in the gym, Moulin was vomiting with fatigue. But he passed the physical test and made two parachute jumps without injuring himself. [2]

He was ready to make a night jump over France by November, but this was delayed until January because of bad weather and lack of aircraft. (The Free French developed something of a persecution complex about this, thinking that the British were obstructing their important mission.)

Finally, after an appeal as high as the foreign secretary Anthony Eden had made sure an aircraft was available, Moulin was dropped on the night of January 1/2, 1942. [5]

From the very start, difficulties arose; he landed several miles off target, was separated with his assistant and wireless operator, and it took several months before Moulin had direct wireless touch with London.

Already the dangers were around corner. Vichy counterespionage service had already discovered a lot about Moulin's acitivities. They knew that a man named Moulin or Mercier, who had formerly been "the prefect of Indre-et-Loire(sic), had left for England as an emissary of "the Intelligence Service". This information had been obtained following the arrest of an SOE agent in France. A report dated October 31, 1941 warned the local office of the Surveillance du Territoire in Marseille to look out for him. [2]

Henri Frenay (He's wearing glasses and mustache as a disguise.)

Emmanuel d'Astier de la Vigerie

Jean-Pierre Lévy

Clandestine papers, published by Combat, Libération, L'Humaité, and Témoignage Chrétien.

General Charles Delestraint

Marquisards

Railroad sabotage by the Secret Army

A result of sabotage

In the southern occupized zone, to which Moulin's initial mission was limited, there were three major non-communist resistance movements, whose leaders were Captain Henri Frenay (Combat), EMMANUEL D'ASTIER DE LA VIGERIE (Libération), and JEAN-PIERRE LÉVY (Franc-Tireurs).

Of these, Frenay was the most important and initially most helpful figure. Frenay shared the idea of unified Resistance and has been pursuing this on his own, independent of Moulin. His Combat was in fact a product of fusion with other groups, and it grew to be much bigger than the other two networks combined.

Frenay wrote about his first meeting with Moulin after his return from London:

It was indeed Jean Mouin. He was overjoyed to see us. He told us of his journey through Spain to Portugal and how his depature for England had been subjected to endless delays. He described his first conversation with General de Gaulle, noting the vivid impression the man had made on him, as well as his stay in London. The resolute courage of the people of that city had deeply affected him . . .

Here at last was what we had so long awaited: contact with Free France, miraculous contact on the highest level! What a powerful spur this would be to our unity drive! We read pure joy in one another's faces. . .

Removing a wad of banknotes from hs hip pocket, [Moulin] chucked me 250,000 francs.

"However, I want you to know that Conlonel Passy's people are very upset by the fact that the various resistance operations - the political, the intelligence, the propaganda services - are so terribly intermingled, even to the point of often being run by the same men. In his opinion this could be disastrous for security. It increases the vulnerability of both units and individuals. They could be knocked out even before they get started. The British Secret Service shares this view, and, after all, they're the ones who have all the resources, especially arms and ammo. All this is by way of explanation for the dispatch that I've brought you."

He then showed several more pages of microfilm that contained extremely precise instructions covering everything down to the tiniest details of our operation. In fact, they were orders.

Chevance and I exchanged a sidelong glance under Max's watchful eyes. [7]

Frenay's reaction characterized difficulty of Moulin's mission for it involved dissolving the existing structure of resistance and imposing the will of Free France. The resistance leaders were willing to accept de Gaulle as the symbolic head. By middle of 1942, Resistance press began to carry the phrase 'Un seul chef de Gaulle' on its masthead. But like Frenay, they balked at the idea of receiving orders from anyone, especially someone sitting in the safety of London.

Secret Army

Nevertheless, Moulin was making progress. He set up Services des opérations aériennes et maritimes (SOAM) for parachute drops and landing and Wireless Tranmissions (WT), both of which were important powerbase for him. He guarded them zealously since they were the conduit through which money, arms, and communication flowed bewteen London and Resistance.

He also set up Bureau d'Information et de Presse (BIP), a central press agency for the Resistance, to furnish clandestine writers and editors with all the information they needed for their journals. It would furnish Resistance with information and propaganda themes from London and also transmit material back to London from France. It would also prepare articles for the British, American, and world press.

He also created Comité Général d'Etudes (CGE), a consultative commission of eminent jurists who would draft a plan for the political, economic, and administrative structures of France immediately after the liberation. Such structures would have to be put in place rapidly to avoid chaos as the Allied troops drove Vichy and the Germans out of power. [4]

Furthermore, after many meetings and discussions, Moulin succeeded in bringing about a separation within each of the Resistance movements between military action and political action. This paved the way to Septmember 1942 when the three movments finally agreed to unite their paramilitary formations into a single Armée Secrète (Secret Army). It was the first important step toward the unification.

Frenay, who was an army captain, argued that he was uniquely qualified to be the commander of the united Secret Army. He certainly was as it was his idea to begin with and his movement would provide about 75 percent of the personnel. He argued that he could not turn over to a stranger thousands of men who risked their lives because of their trust in him.

However, Frenay's rival d'Astier would not budge on the issue. D'Astier and Lévy flatly refused to place their movements under Frenay because he was right-wing and authoritarian. D'Astier insisted that the head of the Secret Army must be a completely independent man with no partisan attachment to any one movement. The compromise was reached when Frenay chose General CHARLES DELESTRAINT, once de Gaulle's commanding officer, as the commander of the Secret Army. [4]

When Frenay asked Delestraint to head the Secret Army, he said:

"General, I must warn you that an acceptance on your part would entail your exposure to mortal danger, a far greater danger than you've ever met on the battlefield. The Gestapo does not spare..."

"Monsieur," he cut in, "mortal danger is the career officer's lot." [7]

On January 26, 1943, the fusion of three movements into a single organ was finalized with the creation of MUR (Mouvements unis de résistance). Its directorate consisted of Moulin and the three resistance leaders: Moulin was the chairman of the directorate, Frenay the military commissioner, d'Astier the political commissioner, and Lévy the commissioner in charge of information and intelligence. The Secret Army would be subordinated to and controlled by the directorate of MUR.

Despite all the disharmony and the personal conflicts that would continue, as they do in all forms of collective human endeavor, the creation of MUR represented the real progress toward the unity of Resistance. [4]

National Council of Resistance

However, the creation of MUR raised an important question that was to divide the Resistance. The Socialists and trade unionists in the Libération proposed to replace the restrictive framework of the MUR directorate with creation of a broader council, something like Resistance National Assembly, on which former political parties would be represented. This proposal for resurrection of political parties was ardently opposed by many of the resistant movements, which blamed the collapse of France on the party politics of the Third Republic and had every intention of replacing the parties themselves in postwar France. Besides, only two of political parties - the Communists and the Socialists - played any serious part in the Resistance. [4]

However, the representation of political parties in Resistance was an attractive idea to de Gaulle. The political parties would include much broader section of the French people. With their presence on a national council of Resistance, de Gaulle could legitimately claim that he represents the whole France rather than just some unknown groups.

This issue became urgent when the Americans found a new French general to replace de Gaulle. Roosevelt saw an ideal candidate in General HENRI GIRAUD or even Vichy commander, Admiral FRANÇOIS DARLAN to great dismay of nearly all the resistants. For Roosevelt, it was not important whether the postwar France was to be a fascist state as long as he could find a docile ally who would shup up and just obey the Allies. He nonchalantly told André Philip, the Interior Commissariat of Free France: "Darlan gave me Algiers, long live Darlan! If Laval gives me Paris, long live Laval! I am not like like Wilson, I am a realist!" Such 'realism' so shocked the Allied public opinion that Roosevelt backtracked by claiming that Darlan was only a 'temporary expedient.'

When the United States reached a deal with Darlan, which would allow him to be the dictator of North Africa, a disappointed resistant member named Fernand Bonnier de la Chapelle, a 22-year-old royalist assassinated him on December 24, 1942. This sparked wide-ranging conspiracy theories since everyone seemed to have a motive - even the Americans who were increasingly embarrassed by Darlan deal. The Gaullists were most suspected, but it seems likely that this was an individual act.

However, Roosevelt was still determined not to recognize de Gaulle and simply replaced Darlan with Giraud even though de Gaulll was the only name that resonated with anti-Nazi Frenchmen inside and outside France.

On February 12, Moulin and General Delestraint went to London to discuss the question of parties with de Gaulle. In one of those tantalizingly ambiguous moment about Moulin, HENRI MANHÈS, whom Moulin had sent to London as his trusted assistant, climbed out of plane Moulin and Delestraint were preparing to board. When Manhès saw, he shouted, "Wait! Don't go, Jean, don't go!" Moulin hesistated, but the French liaison officer in charge of the flight said, "I've got my orders," and pushed Moulin through the plane door. [2]

However, the London trip was unqualified success for Moulin. He would be the permanent delegate in both the northern and southern zone. Moulin was invested with a new mission that was even more daunting and complex. He was to create a single Conseil national de la résistance (CNR) for the entire metropolitan France. Colonel Passy and his assistant, Pierre Brossolette were instructed to work out with Moulin the establishment of the council that would have representation from resistance movements, political parties, and trade unions.

On February 14, 1943, in a ceremony at his private residence in Hampstead, de Gaulle made Moulin a Companion of the Order of the Liberation, the highest honor he could bestow. Colonal Passy, who observed the scene, described it as follows:

Once again I see Moulin, white-faced, in the grip of an emotion which we all shared, upright in front of the General, who said to him in almost a murmur, "Stand in attention," and then continued in that characteristic broken, chanting style - "Sergeant Mercier, we acknowledge you as our Companion in Honor and Victory, for the Liberation of France." And while de Gaulle gave him the customary embrace, a tear of gratitude, pride and unshakeable determination ran down the pale cheek of our comrade Moulin. And since he had raised his face to look up to the General we could once more see the traces of the razor wound he had inflicted on himself in 1940 to avoid giving in under enemy torture. [2]

Moulin's central role in internal Resistance as of Spring 1943

Back in France, Moulin not only would have to bring the disparate resistance movements in the northern zone under the umbrealla of national Resistance, he would have to impose the inclusion of political parties over their bitter objection.

Like in so many things about him, there are conflicting accounts as to whether Moulin was the champion of political parties from the very beginning or initially opposed their inclusion. This may be because he probably had to tell them what they wanted to hear in his role as a mediator.

In any case, it is not hard to see why Moulin would be inclined to include - through parties - the moderates, who always form the bulwark of stability in any democratic government.

The Communists and right-wing nationalists were heavily represented in Resistance, and both of them harbored a radical vision for postwar France albeit differently. Frenay always dreamt that from sacrifice of the Resistance, a new France would emerge. But which France did he mean? Considering his right-wing ideology, his vision of France would have been different from the majority of the French.

A Parisian industrialist André Manuel did a sort of survey of state of resistance and collaboration in France in 1942 and reported its result to de Gaulle. One of his conclusions was that the leaders of the Resistance were showing signs of antidemocratic tendencies. [4]

Moulin was probably too much of a democrat not to include political parties in the postwar reconstruction of the republic. It is likely that he blamed the fall of France more to the mentality of those who "preferred Hitler to Léon Blum" than any party politics.

In any case, on December 14, 1942, Moulin concluded that "movements are not the whole Resistance . . . there are moral forces, trade-union forces and political forces." [13]

Moulin had to bring the CNR into being first by choosing and designating the men who would serve as its directors. He had to create the Secret Army in the north, which only existed in theory but did not yet have specific commanders named and troops assigned. Resistance movements in northern zone, where Colonel Rémy (Gilbert Renault) had played Moulin's role with rather different emphasis, had little contact with each other and had no single response to de Gaulle.

However, depature of Frenay and D'Astier to London faciliated Moulin's mission becuase theire deputies, CLAUDE BOURDET and PASCAL COPEAU were less engaged in power struggles than the founding fathers.

After more meetings and compromises, Moulin could send the good news to de Gaulle. On May 27, 1943, the first official meeting of the CNR took place in a quiet private dining-room in central Paris, 48 rue du Four.

It was an extremely difficult and dangerous meeting to arrange. First it was necessary to find in Paris an absolutely safe house in which so many top men of Resistance could meet. What a catch it would be for the Gestapo if they could have got a wind of it! No one was given the actual address. Instead, each delegate was given another, different address, where a guide would meet them and take them to the final address. [4]

National Assembly of the Underground

This was as close to National Assembly as one could possibly get in the clandestine setting. For the first time since July 10, 1940, all the tendencies of French opinion were once again represented in an assembly.

Besides Moulin as the president of the Council, sixteen men represented the eight resistance movements, six political parties, and two trade unions in the CNR.

Each of three movements in MUR was represented with a total of three seats, and the rest of seats were taken by five nothern movements that participated in Coordinating Committee, organized by Brossolette: right-wing Organisation civile et militaire (OCM), communist-run Front National, Libération-Nord, Ceux de la Résistance, and Ceux de la Libération.

The political parties, rechristened as "tendencies" included the French Communists, the Socialists, the Radical-Socialists and three right-wing parties (Catholic Democrats, Alliance Democratique, extreme-right Fédération Républicaine). The trade unions were represented with delegates from Confédération générale du travail (CGT) and Conédération française des travailleurs Chretiens (CFTC). The wily communists had double representation through their French Communist Party and Front National movement. [4]

Moulin, presiding, restated the aims of Resistance France, as laid down by General de Gaulle:

♦ to prosecute the war,

♦ to restore freedom of expression to the French people,

♦ to re-establish republican freedoms in a state which incorporates social justice and which possesses a sense of greatness,

♦ and to work with the Allies on establishing real international collaboration, both economic and spiritual, in a world in which France has regained her prestige.

CNR's first motion, which was passed unanimously, was that the head of France's provisional government could only be General de Gaulle. Vichy had to be completely repudiated.

The result was decisive. The resolution of CNR was widely reported in the Allied press. Resistance France at last found a voice and spoke loudly. It repudiated Vichy as the legal government of France and sent an unequivocal message to Roosevelt.

The meeting was a huge triumph for Moulin. A mission accomplished.

DANIEL CORDIER, Moulin's secretary in the underground, recalled that afterward they met at an art gallery on the Ile St.-Louis, where there was an exhibition of Kandinsky's work. Moulin asked him to have dinner and they had spent the evening discussing modern art. "He talked almost the whole time because he was very, very happy," wrote Cordier, "that evening he was relaxed, which was extremely rare." [2]

Moulin had every justification to exult on the night of May 27, 1943. He had brought about a kind of miracle, uniting men of very different political views, of highly competitive ambitions and egos, working and fighting under constant stress with their lives on the line in every meeting and every decision, and as such vocal in their opinion on France's future. He had done so against opposition that at times seemed insurmountable. [4]

The Gravedigger of the Resistance

However, such miracle could not be achieved through his persuasive charm and integrity alone, which Moulin had in abundance by all accounts.

In order to bring disparate movements into line, Moulin found it necessary to rely on the tried and true method of carrot-and-stick. This was possible through his monopoly over money, supplies, and wireless transmission from London and his use of budget as a means of control. But this gave rise to accusations of being dictatorial or harboring personal ambition. Like de Gaulle, who clashed with Churchill and Roosevelt, Moulin on many occasions had to fight with the resistance chieftains.

Frenay vs. D'Astier vs. Moulin

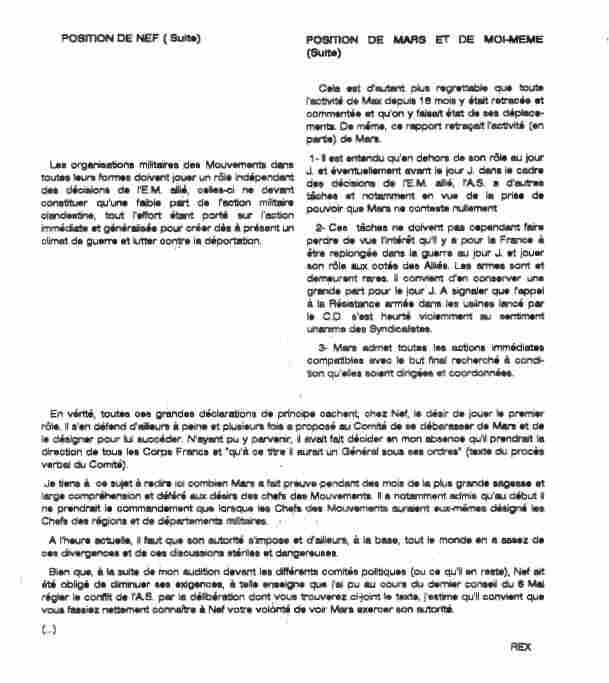

Moulin's report to de Gaulle on the Secret Army dated May 7, 1943, in which he details disagreement between Frenay and himself.

The conflicts within the Resistance often had to do with a petty rivalries of personalities involved as well as their political differences. Frequently, Moulin found himself playing a mediator between Frenay and d'Astier.

Frenay, a patriot whose ideals for France were not very different from Vichy, held talks with a number of Vichy officials inclduing Pierre Pucheu, the interior minister who was an anti-Semitic collaborator. The committee of right-wing Combat supported Frenay and discussed ways of exploiting the double game that some Vichy officials might or might not be playing. The committee believed that Vichy officials were opportunistic and would always try to be on the winning side; so Resistance should convince them it was the Allies who would win.

But others did not look so kindly on Frenay's talk in Vichy. D'Astier was outraged and began waging a campaign of criticism of Frenay and the entire Combat movement. CHRISTIAN PINEAU, the founder of Libération-nord in the northern zone was convinced that Frenay was a secret agent for Vichy military intelligence. Moulin tried to defuse the matter by reassuring Frenay that he understood what he had been trying to do.

For his part, d'Astier, who was an adventurist with a colorful character, caused a stir when he went to London by falsely claiming that he was designated by the Resistance to represent all three movements. His excuse was that he would be a better representative since Frenay was essentially a dull military fellow and an obstinate prima donna who would infuriate everyone in London. Now it was Frenay's turn to be outraged. [4]

Besides such petty clashes, Moulin had to deal with the fundamental difference between the Resistance and de Gaulle's Free France.

Frenay argued to Moulin that London simply did not understand and appreciate the difference between networks, réseaux, which worked for London, and movements, like Combat, which were independent and free.

Moulin told him that he did not seem to understand that they were all at war, and that "in war it is necessary to have one supreme commander, and our commander is General de Gaulle."

Frenay snapped back: "Militarily, yes: politically, no. To put the Resistance at de Gaulle's political disposal would be to go out of our way to confirm the charges of the anti-Gullists that de Gaulle is an apprentice dictator. I must declne." [4]

In 1943, as the relationship between de Gaulle and Churchill worsened, the budget for the Resistance was reduced greatly and Combat's budget was cut in half. Frenay thought that Moulin was hell-bent on weakening his movement.

Frenay began to feel out the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS, precursor of CIA) in Switzerland to exchange intelligence for money. It was at a time when Roosevelt was waging personal war against de Gaulle and sought to destroy his Free French. D'Astier and Jean-Pierre Lévy thought it was a big mistake. "I sensed in them," Frenay wrote, "an unmistakable frustration over Combat's new initiative. Yet their frustrations was nothing compared to Moulin's on his return from France."

Moulin recognized that money was a huge problem, but Frenay's unilateral, independent actions were not acceptable. This was just one of many bones of contention between Moulin and Frenay.

Frenay always accused Moulin of looking at the Resistance through a wide-angle lens and not close up. He argued that Moulin wanted to be the chief of the Resistance but did not know how Resistance functioned on the operative level.

Frenay was probably more qualified on the operational level, but he was most unlikely to get support from left-wing members of the Resistance. In fact, Pascal Copeau, no.2 man in Libération thought that although there was no major difference between the rank and file of the movements, Combat's cadres were "latent fascists . . . or reactionary bourgeois who . . . never pronounced the word Republic except through gritted teeth." According to Copeau, some Libération leaders felt that Frenay's removal was the "greatest service one could render the Resistance at the moment." George Boris of the Interior Commissariat commented, "The ructions [Frenay] could cause in France surpass the imagination."

When Frenay was disillusioned with postwar France, he would lay most of blame on Moulin calling him the gravedigger of the Resistance. [4]

Then Moulin had disputes with the Communists on the strategic issue: namely, immediate action or waiting for D-Day. The Communists wanted to help Soviet Union as much as they could, and to divert German troops from the eastern front, they would have to harass the Germans in France immediately and constantly. Pierre Villon, the Communist head of Front National, argued that "Hitler's war machine had to be hit and weakened bit by bit and day by day" and criticized Moulin for "waiting for D-Day syndrome." Front National continued their attacks on German soldiers in the streets and elsewhere. These terrorist tactics were condemned by de Gaulle and criticized by the Resistance. [4]

Moulin vs. Gaullists

Pierre Brossolette

Moulin faced difficulties not only with the resistance leaders but also with de Gaulle's people in London, who were supposed to assist him. While Moulin was working on the CNR in the southern zone, Colonel Passy and Pierre Brossolette, who were both strongly opposed to the inclusion of parties in the CNR, worked in the northern zone as they saw fit. Coordinating Committee (northern zone's equivalent of MUR) set up by Passy and Brossolette, was composed of only movements which they judged to have the best military potential. D&eaucte;fense de la France was excluded even though its newspaper had the largest circulation of any resistance publication in France. Moulin had no choice but to accept Coordinating Committee as fait accompli had to spend much time mollifying these excluded movements. [13]

Not surprisingly, they reported that the resistance movements in the north voted almost unanimously to exclude the political parties from the CNR.

Moulin knew that they were obstructing his mission and exploded in what Passy described as "a painful incident." How many times did they expect him to fight the same old fights? Why didn't they fight it out with the movements and prepare the way? Furthermore, Moulin had been told by his people that Brossolette had been accusing him of "devouring ambition."

A shouting match ensued at full volume as Brossolette demanded to face his accusers. Here two men of great courage accused each other of personal ambition for postwar France, which neither of them would live to see. (When Brossolette was arrested by the Gestapo, he committed suicide by throwing himself out of the fifth floor of Rennes Prison on March 22, 1944.) Passy reminded them that several of the neighboring apartments were occupied by Germans, but to no avail. Moulin accused Passy of being putty in the hands of his subordinate. They parted on the worst of terms. [4]

Back in London, Passy and Brossolette condemned Moulin in harshest terms. They reported to de Gaulle that Moulin had been entrusted with excessive powers and was out of control. They maintained that although his loyalty was beyond question, he was dependant on a bizarre entourage (Moulin's Air Ministry associates) who were "indoctrinating" him. [2]

The rivalry of Moulin and Brossolette was rather unfortunate byproduct of CNR. Their fundamental disagreement lay in that where Moulin the prefect thought in terms of administration, Brossolette thought in terms of politics. As historian Julian Jackson puts it, Moulin saw de Gaulle as the provisional incarnation of the Republic; Brossolette saw him as a symbol of political renewal. Moulin wanted the Resistance to serve the State; Brossolette wanted it to regenerate the nation. Brossolette once wrote an article in London that the association between a Socialist like himself and an extreme rightist like Charles Vallin showed that the former political conflicts were moribund: one was either for Vichy or against it, 'Gaullist' or 'anti-Gaullist.' This caused English Socialists and liberals to wonder if Brossolette was a proto-fascist. In this sense, he was like Frenay.

But behind these conflicts, one must never forget that these people were living on their nerves, with the prospect of torture and death never far away.

[13]

Moulin enjoyed the respect and support of many resistance leaders, but the list of his enemies grew. His position as a mediator among the quarreling personalities particularly put him in the crossfire.

Frenay regarded him as a menace to the independence and integrity of the Resistance. D'Astier accused him of abusing his power, misusing his funds and reimposing the political chaos of the Third Repubic against universal oppostion. In London, both Frenay and d'Astier spent much time disparaging Moulin to De Gaulle, D'Astier referring to him as "that little appointed clerk." Colonel Passy, whose authority in the metropolitan France was largely taken over by Moulin, believed that the latter had excessive power. Only de Gaulle was unswayed in his faith in Moulin despite the flood of denunciations.

Then there were the French agents of the American OSS, which regarded him as someone workinng to hand France over to a Gaullist military dictatorship. The right-wing faction in Combat was convinced that Moulin intended to put the Resistance under Communist control. The Communists saw him as an obstacle in their efforts to dominate the Resistance. [2]

But most of all, the German and Vichy authorities began to concentrate on a mysterious delegate of General de Gaulle, known only as Max, traveling around France to coordinate the resistance movements.

BACK < < < Top of

Page > > > NEXT

One of the best known secrets of the Second World War is the rancorous relationship among the leaders of Western allies - WINSTON CHURCHILL, Charles de Gaulle, and FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT. (Perhaps this is one of reasons for subsequent rocky relationship between the so-called allies, the United State and France.)

One of the best known secrets of the Second World War is the rancorous relationship among the leaders of Western allies - WINSTON CHURCHILL, Charles de Gaulle, and FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT. (Perhaps this is one of reasons for subsequent rocky relationship between the so-called allies, the United State and France.)