Despite his long and prolific architectural career, Salmona (Castro 1998) remains at the interstice of contemporary architectural history (Frampton 1982, p. 82). He is, unmistakably, one of the silent architects (Smithson, A. and P., 1989, p. 5), whose work may well be described as belonging to what post-colonial critics call “the periphery.” Salmona's œuvre is one of the most significant of those produced on this continent during the second half of the twentieth century. His buildings and architectural complexes display great presence and robustness and speak of a particular reality always related to a sense of place. (Figs. 4 and 5)

Concurrently with the last phase of the Latin American literary boom, a new expressive architectural wave manifested itself in many of the regions South of the Rio Grande. These regions are peripheral to the architectural practices supported by an intelligentsia positioned within an imaginary strip stretching along the Eastern seaboard of the United States, particularly New York and Boston, towards Europe in the East and to Japan and Hong-Kong in the West. One of the significant practices to emerge from the boom of Latin American architecture is that of Rogelio Salmona. Like the work of Eladio Dieste in Uruguay, Juvenal Baracco in Peru, and Luis Barragan in Mexico, Salmona's architecture is marked by a distinct individualism. Salmona's prolific œuvre has been produced within the confines of his own country but his fame resonates throughout the Ibero-American world. Moreover, the significance of Salmona's architecture is, I believe, the result of two important aspects: its syncretism, and its power to provoke wonder. (Fig. 6)

One definition of syncretism is "the combination of different forms of belief or practice" (Webster's, 1974, p. 1182). Syncretism is a powerful idea, particularly well suited to the characterization of an architectural pursuit. Such pursuit, informed by various sources is able to extract ideas and inspiration from them, to be used critically in the form making process and its ultimate product, architecture. This is a far cry from a mere copying or mimicking. Used frequently in such fields as religion and philosophy, syncretism may also serve to describe practices in other realms.

The idea of wonder can be best expressed by a concept emerging from literature. In several of his essays and novels the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier (1967) addresses, describes, and analyzes architecture in a highly suggestive and imaginative prose aided by a conceptual strategy which he coins as "lo real-maravilloso" (the marvelous-real) (pp. 58-70). This notion serves as tool with which to approach and understand that syncretic reality that seems to exist throughout Latin America. The marvelous-real is essentially a strategy, a technique which “is... designed to sharpen our awareness of the astonishing richness of observable reality" (Shaw, 1985, Preface). It follows that the concept of the marvelous-real, first conceived of as a strategy to describe existing reality, is also appropriate to describe its making. Salmona, unknowingly, mines the same vein as Carpentier, constructing a reality as vivid and engaging as that of the writer but this time made of tangible elements and materials. Salmona’s architecture is also an ideal dwelling for Mnemosyne. the Greek Classical Goddess of memory and the mother of all muses. It is Mnemosyne that permeates Salmona's highly evocative architecture, triggering recollections of distant locales and buildings in those who experience it. The architect has incorporated in his buildings the spirit of other architectural practices, those that have astonished him through a lifetime of understanding and making form and places. (Figs. 7 and 8)

For Salmona, the process of design is based on experiences, the impact of forms, landscapes, and the manner in which they are inhabited. He considers architecture to be based on a continuous process of re-creation of those aspects and things that, at a particular time and in a particular place, produced an impact on us.” As he points out (2000):

To make architecture is to remember to re-create. It is to continue in time what others have in turn re-created. It is a revival of elements that already exist. The courtyards, “atarjeas” or troughs, the thresholds, and the transparencies cannot be reinvented. Architecture is in tacit agreement with history, since every work informs the next one; it is the result of a continuous practice in search for the essence (Appendix).

Salmona is in the forefront of those who, rigorously and critically, refer to the past without trying to imitate it. In this manner he is unwittingly following the steps of Carpentier, who had celebrated the existence of readily available material for the artist who could, just by being alert, seize the marvelous reality that surrounds us. (Figs. 9 and 10)

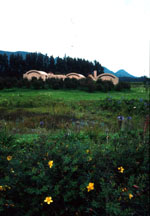

Salmona's architecture engages with all levels of landscape and doing so it creates a true sense of place. Place is, as Ignasí de Solà-Morales (1997) tells us, "...recognition, delimitation, the establishment of confines" (p. 97). Moreover, Salmona's architecture is designed to respond to those elements that are bounded by telluric limits, the horizon, the sky, the mountains in the background, in an attempt to expand the liminal condition of the place. It is an effort directed to recuperate the classic notion of the limit, which according to the Greeks was where things began to manifest themselves, to appear once more. It is at the Sanctuaries of Delphi and Dodona where this concept acquires its full expression. This symbiosis of landscape and architecture has been a constant characteristic of Salmona's works. It can ultimately be understood as an impulse to encompass wherever possible the three natures, which English theoretician, John Dixon Hunt has identified as components of a landscape. If the Classical Greek ideals of architectural composition resonate in Salmona’s architecture, the same can be said of the Japanese tradition of enclosure and Shakkei, or borrowed scenery. (Figs. 11 and12)

This understanding of the landscape resonates also at the intimate scale. Thus, for instance, the appearance of moss in the joints of a brick wall, the action of water over a surface, the demise of a landscape by wind forces and other similar occurrences that leave a trace of nature on the architecture, eventually reducing it to a ruined state are phenomena that Salmona understands well. He is able to control the weathering process through the choice of materials and construction processes that work in unison with the elements. Salmona is aware of the ephemeral quality of architecture when measured in telluric terms, hence his constant impulse to work with, not against, these telluric forces (Holl et al., 1994). At another level, perhaps remote, this fascination with the history and forces of nature speaks of entropy, a concept which was dear to land-art artist such as Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer. (Figs. 13 and 14)

The ultimate task of design is the production of form, claims Christopher Alexander (1964, p.15). This form is the result of a process of differentiation that takes place at various levels ranging from those dealing with ecological concerns to those of a symbolic nature. Between these extremes we find functional and social, as well as experiential elements. At the centre of all these processes it is the body, our bodies that become the point of reflection. The fact is not new. As far back as the first century BC, Vitruvius (1960, p.72), the Roman architect and writer of the first architectural treatise, imparts a significant piece of advice founded on the relation of the body and architecture.

Since Vitruvius’ time, the body has been often the focus of attention of theoreticians of architecture as well as practitioners. Thus the central position that the body plays in the conception and making of Salmona's architecture should come as no surprise. This concern is reflected in three aspects: the choice of materials, the notion of intimacy, and the kinetic quality of his work.

In one of his short essays, the Argentinean writer Julio Cortazar (1983, pp. 22-24) formulates a new way of climbing stairs: going up backwards. In this manner, he claims, the world encompassed by our vision becomes clearer and larger with every step until, at the top, we can view the true horizon. This marvelous architectural allegory can be interpreted as a strategy to discover new facets of the world, provided we are ready to follow an unorthodox plan of action, and remain always open to serendipity. Salmona's buildings also embody hidden paths that permit serendipitous encounters and discoveries. The displacement along each one of their directions constitutes a totally different experience: the return complements the reaching of the objective for it is then that the path, with its inherent characteristics, acquires a new dimension. Returning along the tacit paths in Salmona's buildings is like climbing stairs “à la Julio Cortazar.” His architecture is a vehicle that enhances our bodies’ kinetic and experiential possibilities. (Figs. 15 and 16)

Fig. 13 Casa de Huéspedes, Cartagena de Indias, 1978-81.

Processes of weathering and change on the surface of a patio.

Fig. 14 Quimbaya Culture Museum, Armenia, 1983-86.

Diffentiation through weathering and manipulation of water and brick.

Steven Holl (2000) in his essay entitled “Local Focus/Global Flow” cites a marvelous aphorism by Ovid (1958): “Knowledge of the world means dissolving the solidity of the world.” The process to liquefy this solidity may well lie in the act of dwelling, of experiencing. Salmona points out:

Given its complexity, architecture is not only an aesthetic fact. Architecture has to be lived in; it has to be dwelled in. As we move through built spaces, through architectural spaces, we receive visual, olfactory, auditive, and haptic (tactile) stimuli. They are corners that preserve the emotions and memories of the world. We live in these souvenirs as the stars do in the firmament, always attracted among them.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez said in one of his interviews that to make literature one has to look back, look at one's own literature. One must study it and know it to be able to track at what historical moment we are at the moment of writing.

I agree. The same applies to architecture. It is convenient to look back before stepping forward. Would it not be a waste to disregard the great works of universal architecture? And being American architects, to disregard the great open pre-Hispanic complexes, the subtlety of colonial architecture, the richness of the crossbreeding or "metizage," the simplicity of popular architecture, and the innovations and social content of Modern Architecture?

Yes, indeed. It is convenient to look back, but one must know that at the right moment the gaze has to be withdrawn. It is a matter of recreation and transformation. Not of copying. (2000) (Figs. 17 and 18)

Fig. 17 Uxmal, Mexico. 10th C/

Mayan wall treatment: stacked Chac masks on the East façade of the the “Nunnery Quadrangle.”

1Fig. 18 Archivo General de la Nación, Bogotá, 1988-92.

Ornamental treatment of one of the facades of the complex.

Pathos is the Greek word for emotion. It is a word that conveys multiple meanings, some positive others negative. It is a word with a long history. Pathos refers to experience, to event, to accident, to those things, people, and events that seem to mark us as individuals for a lifetime. A poem, any poem, aptly summarizes the idea of emotion. It is about an emotion experienced by the poet who, moved by the presence of natural elements and forces, creates literary form. In turn, it creates pathos for us the readers. Consider this extraordinary passage by Gabriel Garcia-Marquez in which the writer, referring to Aureliano Segundo, one of the characters in One Hundred Years of Solitude (1970), makes us aware of the evocative power of rain:

He amused himself thinking about the things he could have done in other times with that rain which had already lasted a year. He had been one of the first to bring zinc sheets to Macondo, much earlier than their popularization by the banana company, simply to roof Petra Cote’s bedroom with them and to take pleasure in the feeling of deep intimacy that the sprinkling of the water produced at that time. (p. 322) (Figs. 19 and 20)

Fig. 19 Casa de Huéspedes, Cartagena de Indias, 1978-81.

One of the many fountains found in the patios of the building.

Fig 20. Quimbaya Culture Museum, Armenia, 1983-86.

A true example of wet architecture.

Like poetry, architecture is, above all, about pathos. It is about the impact that natural annd human-made dwelling forms have on us. This pathos is the force that nourishes architectural creation. As Vincent Scully (1962) has pointed out: "To make anything in architecture, which has always been a large-hearted art, it is necessary to have loved something first" (p. 42). To have loved something implies to have formed an emotional bond with that something, to have had a pathetic relationship with it. Pathos is ultimately about experience. Salmona is captivated by these concepts, whose implications David Abram (1996) has clearly articulated: “Only by affirming the animateness of perceived things do we allow our words to emerge directly from the depths of our ongoing reciprocity with the world (p. 56)”.

A component of pathos is the idea of passion. It should not come as a surprise that the concept of passion is one of the basic themes of classical mythology and universal literature. The concept is also intrinsically related to a meaningful practice of architecture: first it is a demanding process, second it is an extraordinary force that moves humans to make exceptional things or to do extraordinary feats. It is the passion for the "quehacer," the everyday making, that nourishes Salmona's practice as well as his success. It is also his willingness to follow the arduous path of a demanding profession in which constraints are increasingly the norm rather than the exception. It is finally his ability to involve his work in a process of syndesis, that is a process dictated by the urge to bind together (Webster’s 1974, p. 1182). And is it not ultimately syncretism—transculturalism, to locate this query within the limits of this conference—a typical example of syndesis? (Fig. 21)

Fig. 21 Alto de Pinos, Bogotá, 1975-81

The name of the place results from the old pine trees preserved within the building. Rogelio Salmona at the entrance on the right side.

APPENDIX

McGill University. School of Architecture

An Architectural Experience

By

Rogelio Salmona

Text of the lecture given at the School of Architecture on 28 March 2000.

I

Introductory Remarks (original version in French)

Je remercie la Faculté d’architecture de l’université McGill cette généreuse invitation pour exposer mon travail, et à vous tous, Messieurs et Mesdames et chers amis, votre présence dans cette salle.

Je dois dire que j'éprouve une grande satisfaction d'être a nouveau au Canada permis vous.

Je désire vous transmettre avec des images et des mots l'émotion que j’ai éprouvé moi même quand j’ai du résoudre dans un endroit quelconque de la Colombie une composition architecturale.

Ce que j’essaye de faire avec l’architecture, comme l’a dit Le Corbusier, “plus qu’un métier c’est une tournure de l’esprit.” C’est offrir à la société a la quelle j’appartiens une réponse sensible et intelligente, si possible, à ses besoins matériels mais aussi spirituels.

Je veux vous montrer avec toute simplicité les buts et les solutions, l'expérience que j’ai suivi depuis 1960, à mon retour en Colombie après avoir fait un séjour de plus de 9 ans à l’atelier Le Corbusier.

A Paris: en effet c’est dans son atelier que j’ai tout le temps pour penser l’architecture que je devais faire (non celle que je pourrais faire) à mon retour en Amérique. C’est cette expérience et son itinéraire que je vais essayer de vous transmettre ce soir.

II

An architectural Experience (original version in Spanish)

Architecture is a way of seeing the world and of transforming it.

It is a cultural fact that proposes and, in certain instances, provokes civilization. It is an intelligent synthesis of experiences and spaces, and of a handful of nostalgia.

It is also the gaze that traverses with rigor and enthusiasm the little things of life, that sublimates the everyday, that resolves for example, the function of a window because through it the landscape comes indoors, or the design of a courtyard which allows man to discover the stars and to limit the infinite.

And architecture owes as much to the everyday as to the most spiritual elements in art. I t helps resolve man's small problems, but, at the same time, it is in charge, of the great themes of civilization and of the great works of universal culture. It transforms nature and molds the city. It is the pulse of a place and a meeting place for reason and poetry, for clarity and magic.

But this wisdom is not only knowledge. It is a spiritual heritage that emerges* when a given stimulus excites memory, awakening the souvenir.

Architectural knowledge, therefore, is nothing less than the fruit of a continuous theoretical and project search; a work through which one attempts to capture -although this cannot ever be fully accomplished. Man's dream to create his own place or, as Gaston Bachelard would say: his own niche in the world.

To make architecture is to remember to re-create. It is to continue in time what others have in turn re-created. It is a revival of elements that already exist. The courtyards, atarjeas or troughs, the thresholds, and the transparencies can not be reinvented. Architecture is in tacit agreement with history, since every work informs the next one; it is the result of a continuous practice in search for the essence.

It constitutes a deep cultural act, since it is not possible to recreate the unknown. On the contrary, it is wisdom that permits choice and selection, and this is the great moment of creation. The moment in which, as happens in music, one begins to compose, to transform what exists, to elaborate the form, to define the particular spatiality of each work. It is the moment that establishes architecture's spirituality.

Given its complexity, architecture is not only an aesthetic fact. Architecture has to be lived in; it has to be dwelled in. As we move through built spaces, through architectural spaces, we receive visual, olfactory, auditive, and haptic (tactile) stimuli. They are corners that preserve the emotions and memories of the world. We live in these souvenirs as the stars do in the firmament, always attracted among them.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez said in one of his interviews that to make literature one has to look back, look at one's own literature. One must study it and know it to be able to track at what historical moment we are at the moment of writing.

I agree. The same applies to architecture. It is convenient to look back before stepping forward. Would it not be a waste to disregard the great works of universal architecture? And being American architects, to disregard the great open pre-Hispanic complexes, the subtlety of colonial architecture, the richness of the crossbreeding or "metizage," the simplicity of popular architecture, and the innovations and social content of Modern Architecture?

Yes, indeed. It is convenient to look back, but one must know that at the right moment the gaze has to be withdrawn. It is a matter of recreation and transformation. Not of copying.

To withdraw the gaze, but also to keep it deeply when one traverses the centenary plazas, the forgotten courtyards, the galleries and entrance thresholds that have witnessed history's parade, to find in the silence it own resonance. To keep the gaze in order to measure and draw all those places that move us so we can keep them in the memory so we can one day remember their measures, echoes, resonance to compose, recharging the architectural work with emotion, the surprising spaces, the meeting places.

Memory helps to find the way of poetry. It helps to discover that it is possible and necessary compose with the material, with light and shadows, with humidity, with transparency and skewed views to achieve an enriched spatiality for the senses.

Different to the other arts, architecture, substantially abstract although utilitarian in material terms, is conditioned by the events and the context of which it is part. One of its characteristics is that it has to have a clear concept of reality, that is it must be able to evaluate what it is its own; must know how to extract from the bottom of its own geography and culture the solutions that fit best the needs and behaviors. Architecture should never drift away from its time or its people.

But it must go beyond.

It must propose spaces that induce emotion, which can be apprehended with the sight but also with the senses of smell and the touch, with the silence and the sound, the luminosity and the penumbra and the transparency that can be traversed allowing the discovery of unexpected spaces.

As for me, I prefer the architecture that allows me to hear the resonance of the emotions, And I am moved by those architectures that allow a glimpse of the trembling hand that builds them and constructs them, with its doubts, its mistakes and attempts as silent notes in the final result.

Above all its doubts. Doubt always generates discovery, it allows distancing from ideological schemes, it forces thought and the seeing of things with the eyes without prejudice.

Doubts but also certainties. One of them is the nearing, ever closer, to the place where architecture is composed and is constructed.

To know how to interpret this is a way to enrich it.

Architecture, then as functional problem, efficient, as a cultural act, collective and historical, but also architecture for the landscape, and architecture for the senses.

The best architecture is, I believe, that which transforms without modifying, which unveils slowly with emotion and that is capable of proposing spaces that enchant, make one happy and surprise. That is profound poetics.

Translated by Ricardo L. Castro. 28-March-2000

WORKS CITED

Abram, D. (1996),The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Vintage Books.

Alexander, C. (1964) Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ashcroft, B. Griffiths, G and Tiffin, H., Key Concepts in Post-Colonial Studies. New York: Routledge.

Calasso, R. (1993).The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony.Toronto: Vintage Books.

Calvino, I. (1993) Six Memos for the Next Millennium. New York: Vintage Books.

Carpentier, A. (1967) Tientos y Diferencias .Montevideo: Editorial Arca, 1967.

Carter, P. (1988) The Road to Botany Bay: An Exploration of Landscape and History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Case, E. S. (1997) The Fate of Place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Castro, R. L. (1998) Rogelio Salmona. Bogotá: Villegas Editores.

Castro, R. L. (1997) A Draft of Shadows. On Experiencing the City [on line] Montreal: Galerie Optica. Available from: