It is September, and the nation is again reminded of the Bells of Balangiga, which remain unreturned to the Philippines.

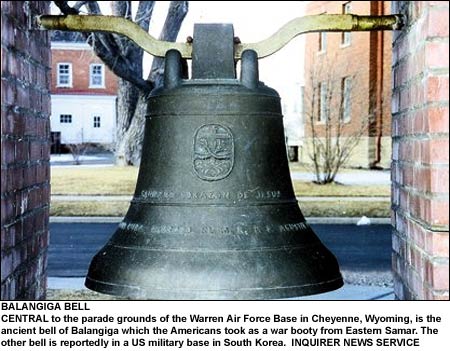

The fate of these controversial bells, at least the two with the Balangiga identification now displayed at the F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming, USA, remains in limbo. And recent high-profile diplomatic attempts to have these relics returned to the country have resulted in failure.

There is "no softening of grounds from the (American) side," said retired Colonel Gerald Adams, who recently published The Bells of Balangiga, a book that erroneously charts the history of the two bells and a 15th-century Mary Tudor cannon in Wyoming. Adams relayed his bleak comment to Jean Wall, daughter of Private Adolph Gamlim, the first soldier of Company C, US Ninth Infantry Regiment, to be attacked during the infamous "Balangiga Massacre" in the morning of September 28, 1901.

Jean Wall visited Balangiga, the scene of his fatherís life-long nightmares, in September last year. Her story was featured by the Associated Press soon afterwards. But the item did not mention the fact that she also joined the Balangiga Historical Tour, a centennial activity I helped coordinate for the University of the Philippines and participated in by more than 350 university officials, professors, personnel and students from different autonomous units of UP.

During a tour-related symposium held in Tacloban, Jean publicly performed a ritual embrace of reconciliation with Engineer Ted Amano, president of a group of Manila-based natives of Balangiga. Amano is a descendant of a Filipino attacker who fitted the description of one that inflicted some of Pvt. Gamlinís wounds. This display of reconciliation and peace at the descendant level between Jean and Ted, which had been photographed and videotaped for posterity, sharply contrasts with the hostile official American attitude towards the return of the bells.

Several months later, Jean sent me photocopies of documents, published articles, and other items from her fatherís archives. Along with a draft screenplay for the Balangiga movie sent earlier by Bob Couttie for my comments, these materials further improved my knowledge and grasp of the Balangiga event.

In answer to a recent e-mail asking for new information about the origin of the two Wyoming bells, I again told Jean my belief that none of these bells were possibly rung during the Filipino attack on the American garrison in Balangiga. These bells were probably looted from other Samar towns. At least none of the two have the unique details of a smaller bell in an extant photograph with some Balangiga survivors, which the late Pvt. Gamlin claimed was taken in Manila. Of note, Pvt. Gamlin mentioned the ringing of only one bell in a published American account of the massacre.

I believe the authentic Balangiga bell, the one photographed with the survivors, is the "third bell" that has always been in the possession of the US Ninth Infantry Regiment, now stationed at Camp Hovey near Tongduchon, South Korea. It is the return of this bell in time for the centennial of the Balangiga Massacre two years from now that should be the focus of our efforts and attention. We would not only rid ourselves of the strong opposition from congressional politicians and veterans groups from Wyoming. Our quest for this bell also has the support of some former officers of Company C and key descendants of the American victims in Balangiga.

The "third bell" of Balangiga in Korea was last seen in April 1997 by Major Daniel N. Tarter, former commander of Company C. In a letter to a newspaper correspondent, he proposed the return of this bell, and the Wyoming bells, to Balangiga. Later, Tarter was reportedly harassed by and received hate calls and mails from fellow Americans for his proposal. I feel sorry for him.

I have not yet established the true source of the bell dated 1863 in Wyoming. As for the bell dated 1889, I first thought this belonged to Basey town, a former parish assignment of Father Agustin Delgado, the priest whose name was inscribed on the bell. I ruled this out soon after I learned that Fr. Delgado was no longer in Basey in 1889. Lately, I placed importance on the number "1900" that was neatly scratched above the Franciscan emblem on this bell. If this number represented the year 1900, this would match Fr. Delgadoís parish assignment in Guiuan town, the possible origin of the bell. (With this theory is the presumption that Fr. Delgado was a Filipino; the Spanish priests were expelled from the islands in 1898.)

Guiuan is also my theorized origin of the Tudor cannon displayed near the Wyoming bells. After all, this town had a Spanish fort armed with several cannons to watch out for the Dutch Navy in the early 1600s. Thus the 15th-century cannon, like the 1889 bell, was probably taken from Guiuan, and not from Balangiga.

The Wyoming relics appeared to have been shipped out of the former Camp Bumpus, the American military headquarters on the site of the present Leyte Park Resort in Tacloban. The Balangiga bell of Company C followed a different route that did not include Leyte.

September 10, 1999