Casi sin saberlo, un

joven pandillero del "área de la bahía", un suburbio pobre del norte

de Los Angeles, inauguró a fines de 1979 el boom del crack -la mortífera

alteración de la cocaína que está arrasando literalmente a la población

negra de las principales ciudades estadounidenses- cuando comenzó a recibir, de

un exiliado nicaragüense, ingentes cantidades de cocaína pura.

Casi sin saberlo, un

joven pandillero del "área de la bahía", un suburbio pobre del norte

de Los Angeles, inauguró a fines de 1979 el boom del crack -la mortífera

alteración de la cocaína que está arrasando literalmente a la población

negra de las principales ciudades estadounidenses- cuando comenzó a recibir, de

un exiliado nicaragüense, ingentes cantidades de cocaína pura.

Rick Ross revolucionó el mercado de las drogas: por más que su abastecedor, Danilo Blandón, le entregaba la mercadería a precios tentadores, la cocaína era por entonces muy cara, y por tanto reservada a los consumidores de clase media y los intelectuales. Ross experimentó con el método del blow up, cocinando la cocaína mezclada con un anestésico llamado procaína, y logró transformar el polvo en rocas, que podían ser fumadas en pipas. Creyó haber reproducido la "base", un estado primario de la cocaína que se suele fumar en los países productores de América Latina. Por cada quilo de cocaína, Ross lograba tres quilos de rocas. El furor inicial del crack mató a los atletas Len Blas y Don Rogers y casi liquidó al actor Richard Pryor; después se convirtió en "la cocaína de los pobres", y hoy provoca una virtual devastación de la comunidad negra de Estados El 18 de agosto pasado, después de un año de una meticulosa investigación, un diario de Los Angeles, el San José Mercury News, (para ver la historia completa: www.sjmercury.com/drugs/start.htm) comprobó que el boom del crack en California -y su irradiación al resto del país- es directa responsabilidad de la central de inteligencia (CIA) y de una organización antisandinista, que organizaron el tráfico de cocaína a Los Angeles para financiar a los contras nicaragüenses a comienzos de 1980.

La explosiva revelación provocó indignación entre las organizaciones de la minoría negra estadounidense, que llegaron a denunciar la participación de organismos estatales en la "fundación" del comercio del crack como una agresión planificada contra los negros. En el Congreso de Estados Unidos, en cambio, la sólida información del San José Mercury reactualizó el costado más oscuro del escándalo Irán-Contras, ventilado en noviembre de 1986: a pesar de los numerosos testimonios, el gobierno de Ronald Reagan logró en aquel entonces enterrar la investigación sobre la forma en que se financió la asistencia secreta de Estados Unidos a los contrarrevolucionarios nicaragüenses. Ahora, las evidencias confirman que el Consejo Nacional de Seguridad y la CIA traficaron cocaína a fin de obtener los recursos para la compra de armas, que el Congreso había embargado.

Las consecuencias de la revelación son impredecibles: no sólo cientos de miles de ciudadanos estadounidenses resultaron víctimas de esas operaciones encubiertas; también surge con claridad que durante diez años diversos organismos gubernamentales (el Pentágono, la CIA, la DEA, el Departamento de Justicia) ocultaron pruebas, destruyeron archivos y manipularon la información para impedir que pudiera conocerse la participación estatal en el tráfico de drogas. No es menor el hecho de que muchos de los traficantes involucrados en esas operaciones encubiertas son hoy agentes secretos estadounidenses afectados a la lucha contra la droga.

Pero la responsabilidad en la financiación mediante droga de las operaciones encubiertas no es exclusiva de los organismos estadounidenses. La información del San José Mercury permite ensamblar los trozos de una historia fragmentada donde los polifacéticos miembros de esa trasnacional terrorista conocida como Operación Cóndor (agentes de inteligencia, torturadores, extorsionadores, traficantes) aparecen con papeles muy destacados. Del esquema surge una conclusión: el narcotráfico, ahora identificado como el enemigo principal de la seguridad hemisférica, fue el recurso preferido de la Doctrina de la Seguridad Nacional para desplegar el terrorismo de Estado por todo el continente.

Suárez Mason, directamente implicado en los asesinatos de Zelmar Michelini y Héctor Gutiérrez Ruiz y protector de Aníbal Gordon (jefe de las bandas paramilitares que operaron en los centros clandestinos de detención subordinados al primer cuerpo de Ejército, y especialmente en Automotores Orletti, de donde desapareció más de un centenar de uruguayos), fundamentó la necesidad de desarrollar la lucha anticomunista en América Central, a partir del triunfo sandinista. El general miembro de la P-Due comprometió la creación, en el seno del Batallón 601 (la estructura de inteligencia del Ejército) de un Grupo de Tareas Exterior, GTE, para desplazar hacia América Central un contingente de "asesores", que trasmitiría a los ejércitos y a los comandos paramilitares de la región la experiencia argentina en la "guerra sucia".

Los 8 millones de dólares que la WACL aportó para los gastos iniciales del GTE son el primer y temprano indicio de la asistencia encubierta estadounidense que después instrumentó el coronel Oliver North, por encargo de Reagan y George Bush. Pero la aventura centroamericana (y el enriquecimiento personal de sus protagonistas) requeriría fondos mucho más cuantiosos. Al momento del congreso de la CAL Suárez Mason ya tenía prevista una fuente significativa de financiamiento: un suministro ilimitado de cocaína boliviana.

Ese punto fue el centro de los contactos informales que Suárez Mason mantuvo en Buenos Aires con el salvadoreño D'Aubisson

-yerno del general Amaury Prandt, exjefe de la inteligencia militar uruguaya- y el italiano Delle Chiaie -líder de la organización fascista Avanguardia Nazionale, responsable del atentado contra el dirigente democristiano chileno Bernardo Leighton, perpetrado en Roma por encargo del jefe de la policía secreta de Pinochet, el general Manuel Contreras.

Ambos habían acordado con el coronel boliviano Luis Arce Gómez el suministro de droga para financiar acciones paramilitares, como parte de un plan más vasto y complejo. En realidad, a comienzos de 1980, los militares golpistas y los narcotraficantes bolivianos coincidieron en sus intereses. De ahí surgió la "narcodictadura" del general Luis García Meza que, con el pretexto de combatir a la "izquierda comunista", controló el poder en Bolivia durante dos años. El propósito del golpe fue eliminar el monopolio de los cárteles colombianos que asignaban a los barones de la droga bolivianos un papel secundario, limitado a la producción de pasta base, con una interdicción para la instalación de fábricas de cocaína.

En marzo de 1980, el agente secreto de la DEA Michael Levine, estacionado en Buenos Aires, descubrió que un trust de narcotraficantes bolivianos impulsaba el golpe militar, financiando la operación. La CIA y la DEA ocultaron la información al gobierno de Jimmy Carter y permitieron que prosperara el plan.

En el esquema, el coronel Arce y su primo Roberto Suárez, principal narcotraficante, se comprometieron con D'Aubisson y Delle Chiaie a aportar dinero para América Central si, a la vez, ellos facilitaban el tráfico para financiar el golpe.

Como consecuencia, la dictadura argentina apoyó el golpe de García Meza, desplazando en julio de 1980 a unos 400 "asesores", aportando apoyo logístico (en armas y en vehículos) y destinando casi 800 millones de dólares en asistencia económica al nuevo régimen. Hoy se sabe que buena parte de esa "ayuda" fue en realidad un pasamanos de narcodólares, aportados por los traficantes y "lavados" por los agentes argentinos en Centroamérica.

Miori se desplazó después a Centroamérica, oficiando de "correo". Se le atribuye un papel fundamental en la organización del tráfico de drogas que fluyó hacia El Salvador. La cocaína era trasbordada en las bases de la Fuerza Aérea salvadoreña y derivada hacia Estados Unidos. Parte de la droga financió los escuadrones de la muerte montados por el mayor D'Aubisson y los grupos paramilitares guatemaltecos asesorados por el teniente coronel Santiago Hoya, alias "Santiago Villegas", otro miembro clave del grupo de asesores argentinos en Centroamérica. Miori murió en un confuso incidente en 1982, después de que se comprobó que había desviado en su propio provecho dinero destinado a la paga de los asesores argentinos.

El teniente coronel Hoya y el coronel José Osvaldo Ribeiro, alias "Balita", responsable máximo del GTE, tuvieron una decisiva participación en los orígenes de lo que después fue el escándalo Irán-Contras. Ribeiro, a quien se le atribuye una intervención protagónica en la desaparición de exiliados en el marco de la Operación Cóndor, así como en la modernización de los servicios de inteligencia en Paraguay, trasladó las experiencias de coordinación realizadas en Argentina con militares uruguayos, chilenos y paraguayos.

Desde su cuartel general en el hotel Honduras Maya de Tegucigalpa, Ribeiro comenzó la coordinación con los exiliados de la Guardia Nacional Somocista, mientras Hoya, como "jefe de operaciones", dirigía la instalación del campo de entrenamiento llamado Sagitario, en las afueras de Tegucigalpa, y del campo de concentración clandestino conocido como "La Quinta". Hoya y Ribeiro estrecharon contactos con el general Gustavo Alvarez Martínez, jefe del G2 del ejército hondureño, con el excapitán de la Guardia Nacional somocista Emilio Echaverry y con los líderes "contras" Arístides Sánchez, Enrique Bermúdez y Frank Arana. De hecho, la CIA había delegado en los asesores argentinos la organización de la "contra" nicaragüense; Ribeiro y Hoya tuvieron una actuación destacada en las negociaciones que culminaron con la creación de la segunda dirección colectiva de los "contras", tras la trans Cuando comenzaba a organizarse la "narcofinanciación" de esas operaciones encubiertas, los asesores argentinos instruyeron a los paramilitares centroamericanos en las prácticas de los secuestros extorsivos, que tantos dividendos habían dado en Buenos Aires, Córdoba y Rosario. El flujo de dinero en grandes cantidades para la compra de armamento y pago de los mercenarios se materializó recién cuando la CIA se embarcó decididamente en el ingreso de droga al territorio estadounidense. La investigación del San José Mercury confirma ahora el papel decisivo de uno de los "ahijados" preferidos de los asesores argentinos: el coronel nicaragüense Enrique Bermúdez provocó el salto cualitativo cuando autorizó a dos conciudadanos, Danilo Blandón y José Norwin Menenes, a montar el tráfico de drogas, utilizando la incipiente estructura de la FDN en Los Angeles.

Coordinado

el tráfico por los argentinos, la droga boliviana era depositada en las bases aéreas

salvadoreñas y desde allí trasladada en avionetas hasta aeropuertos de Texas,

con la protección de la CIA. A fines de 1981, la estructura había logrado

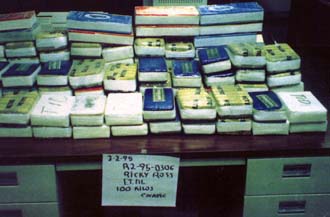

contrabandear una tonelada de droga. Blandón, quien actualmente cobra un sueldo

del gobierno estadounidense como agente especial de la DEA, admitió que entre

1981 y 1988 se llegó a introducir hasta 100 quilos semanales de cocaína.

Coordinado

el tráfico por los argentinos, la droga boliviana era depositada en las bases aéreas

salvadoreñas y desde allí trasladada en avionetas hasta aeropuertos de Texas,

con la protección de la CIA. A fines de 1981, la estructura había logrado

contrabandear una tonelada de droga. Blandón, quien actualmente cobra un sueldo

del gobierno estadounidense como agente especial de la DEA, admitió que entre

1981 y 1988 se llegó a introducir hasta 100 quilos semanales de cocaína.

Los argentinos fueron también los pioneros de la estructura que después utilizó el gobierno de Rea-gan para canalizar la ayuda encubierta a los contras. Los agentes del Batallón 601 Raúl Guglielminetti (alias "Mayor Guastavino"), Leandro Sánchez Reisse (alias "Lenny") y Jorge Franco (alias "Fiorito") se especializaron en el lavado de dinero de los fondos provenientes del narcotráfico.

Franco viajó en dos oportunidades a Centroamérica, en una de ellas con su identidad real. Calificado como experto en finanzas, Franco figura como "desaparecido" en las listas del Instituto de Obras Sociales del Ejército, pero se sospecha que por lo menos hasta 1987 permanecía en Centroamérica.

Leandro Sánchez Reisse es el único de los miembros del GTE que ha confesado la vinculación de los asesores argentinos con el narcotráfico para la financiación de las operaciones encubiertas. Sánchez Reisse, de profesión contador, fue detenido en Ginebra, Suiza, en 1982, cuando intentaba cobrar el rescate del banquero uruguayo Carlos Koldobsky, secuestrado en Buenos Aires. En 1985 logró fugar del presidio de Champ Dollon. Se refugió en Estados Unidos, bajo la protección de la CIA. Para evitar la extradición, Sánchez Reisse se ofreció para testimoniar ante la subcomisión de Terrorismo, Narcóticos y Operaciones Internacionales del Comité de Relaciones Exteriores del Senado estadounidense.

Sánchez Reisse reveló, en fechas tan tempranas como 1987, que el general Suárez Mason y el sector del ejército bajo su mando recibieron dinero del narcotráfico para financiar la lucha contrainsurgente en América Central. Explicó que dos empresas montadas en Miami -una llamada Argen-show, dedicada a la contratación de cantantes para giras latinoamericanas, y otra llamada Silver Dollar, en realidad una casa de empeño dirigida por Raúl Guglielminetti- fueron las pantallas para la manipulación del dinero.

Admitió que Silver Dollar y Argenshow habían canalizado 30 millones de dólares del narcotráfico que fueron girados, vía Panamá, hacia Suiza, Lichtenstein, Bahamas e Islas Cayman. El dinero, dijo, terminó en manos de los contras nicaragüenses. Reveló también que la CIA estaba al tanto de las actividades de las dos empresas de Florida desde mediados de 1980, y que dio su visto bueno para las operaciones de lavado.

El escándalo Irán-Contras reveló, en su momento, el involucramiento de la CIA en el tráfico de drogas. La participación argentina y boliviana, y acaso la chilena y la uruguaya, han quedado sumergidas al amparo de las soluciones "políticas" que extendieron la impunidad para los violadores de los derechos humanos. Las nuevas evidencias demuestran que el narcotráfico fue -y quizás siga siéndolo- un soporte para el despliegue de operaciones encubiertas. Todos esos elementos descalifican ahora el objetivo impulsado por el Departamento de Defensa de Estados Unidos, que presiona en América Latina por la militarización de la guerra contra el narcotráfico. Los antecedentes, que en su momento llevaron a las dictaduras a instalar una estrategia que combinó el despliegue del terrorismo de Estado y el enriquecimiento personal, cuestionan los propósitos de crear una fuerza militar multinacional para combatir lo que se prese

![]()

May 11, 2000

Concluding its investigation into allegations of CIA complicity in drug trafficking to the United states during the 1980’s, the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) today released a detailed report which concludes that evidence does not support those allegations, made initially in a newspaper series entitled "Dark Alliance." The allegations, reported in the San Jose Mercury News in August 1996, posited that the CIA was complicit in drug trafficking to the United States as part of its effort to assist the Nicaraguan Contras in their armed conflict against the Sandinista government. These allegations generated enormous public concern and discussion and resulted in a variety of inquiries. In addition to the HPSCI investigation, there have been two Inspector General inquiries (one at the Department of Justice and one at the CIA), a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department review, and a spate of news media investigations. The HPSCI report, which was adopted unanimously, concludes with seven findings.Those findings are:

The Committee found no evidence to support the allegations that CIA agents of assets associated with the Contra movement were involved in the supply of sale of drugs in the Los Angeles area;

The Committee found no evidence to support the allegations that Norwin Meneses, Danilo Blandon, or Ricky Ross were CIA agents or assets, or that their drug trafficking was intended to further the cause of the Contras. Although Norwin Meneses and Danilo Blandon were sympathetic to the Contras, and were trafficking in narcotics, they were not associated with the CIA.

Finally, the Committee found no evidence to support the claims that drug traffickers such as Ronald Lister, Carlos Cabezas, and Jorge Zavala were associated with the CIA;

The Committee found no evidence to support allegations that employees of the CIA engaged in narcotics trafficking in the Los Angeles area;

The Committee found no evidence that any other US intelligence agency or agency employee was involved in the illegal supply or sale of drugs in the Los Angeles area; One Contra faction, the Southern Front, did receive support from individuals who were engaged in drug trafficking from Central America to the United States. Certain Southern Front organizations apparently accepted support from drug traffickers knowingly, particularly when their support from the CIA ended; The CIA as an institution did not approve of connections between Contras and drug traffickers, and, indeed, Contras were discouraged from involvement with traffickers. Also, CIA officers on occasion notified law enforcement entities when they became aware of allegations concerning the identities or activities of drug traffickers; and In the case most relevant to the "Dark Alliance" series, it appears that the support Blandon and Meneses gave a Contra chapter in California was financed from illegal drug proceeds since this was their main source of income. Nevertheless, their support was limited (reportedly between $30,000 and $50,000) and was not sufficient to finance the organization. The support to the Contras provided by Meneses and Blandon did not consist of "millions" to the Contras, as alleged by the Mercury News. The Committee found no evidence that the CIA or the Intelligence Community was aware of these individuals’ support of the Contras.

In summarizing its findings, the Committee stated: "The allegations of the ‘Dark Alliance’ series warranted an investigation, and the Committee performed its role mindful of the thousands of American lives that have been lost to the scourge of crack cocaine. Based on its investigation, involving numerous interviews, reviews of extensive documentation, and a thorough and critical reading of other investigative reports, the Committee has concluded that the evidence does not support the implications of the San Jose Mercury News—that the CIA was responsible for the crack epidemic in Los Angeles or anywhere else in the United States to further the cause of the Contra war in Central America." The Committee focused its inquiry in four areas, including instances involving reporting requirements for narcotics information and the hand-off of such information among the various agencies of jurisdiction. The Committee was concerned by evidence that during the Contra program the CIA made use of, or maintained relations with, a number of individuals associated with the Contras or Contra supply effort about whom the CIA had knowledge of information or allegations indicating that the individuals had been involved in drug trafficking. The Committee’s report includes a detailed discussion of the guidelines and policies in effect during the 1980’s and today. Under current procedures, before an individual with a criminal history or allegations of criminal activity, including drug trafficking, can be used as an asset, high ranking CIA officials must determine that the potential value of the person’s information outweighs any negatives for the United States associated with the establishment of a relationship with the CIA. In releasing the report, Committee Chairman Porter J. Goss (R-FL) noted the exhaustive nature of the review conducted by his panel. "The explosive nature of the story and the seriousness with which we view allegations of complicity in narcotics trafficking by any official US agency led us to go the extra mile in our inquiry. I am satisfied that we chased down all relevant leads and covered the necessary ground, and that the findings of this report are fully supported by the facts.

Bottom line: the allegations were false," Goss said. Ranking Member Julian C. Dixon (D-CA) stated that "all of the issues raised by the Mercury News articles were addressed in the investigation. I believe that the committee’s effort, together with the work of the Justice Department and CIA IG, thoroughly examined those issues." The Committee conducted its own interviews, including interviews of seven former US government officials who had refused to be interviewed by the CIA Inspector General. The Committee thoroughly reviewed and assessed the findings of the CIA and DoJ Inspectors General as presented in their final reports. Tens of thousands of pages of documents (classified and unclassified) were also reviewed. "I am pleased to offer this comprehensive report to the American people, although I suspect that there remain some who will not accept our conclusions. It saddens and troubles me that allegations of this kind would be so believable to so many people, even though the facts indicate otherwise, and even in the face of repeated investigations that have concluded otherwise. As Chairman of the committee with oversight responsibilities for the Intelligence Community, I take it as part of my job to improve the credibility our security agencies have with the public. I am hopeful that the unanimous and bipartisan findings of our Committee in this case will help in that regard," Goss said. Dixon noted that the investigation revealed that the question of leniency for government informants should be a matter of continuing concern within the US criminal justice system. "Disparity of treatment accorded to those involved in the drug trade has clearly led to public skepticism about the basic fairness of the judicial system and should be addressed by appropriate committees of Congress," Dixon said.

![]()

Otro punto de vista

Robert Parry (The Consortium)

While seeking to clear itself of drug-trafficking guilt, the CIA has acknowledged that cocaine traffickers played a significant early role in the Nicaraguan contra movement and that the CIA intervened to block an image-threatening 1984 federal inquiry into a cocaine ring with suspected links to the contras. The CIA also admitted that it received intelligence from a law-enforcement agency as early as 1982 that a U.S. religious group was collaborating with the contras in a guns-for-drugs operation. But the CIA turned a blind eye toward the allegations, claiming that to do otherwise would violate the civil liberties of the religious group whose identity remains secret. The troubling admissions are buried deep in a Jan. 29 report whose main purpose is to bolster the spy agency's denunciation of a 1996 series by Gary Webb, then a reporter for the San Jose Mercury News. That series linked CIA-backed contra operatives to the explosion of the nation's crack cocaine epidemic in the early 1980s. In the report's volume one, entitled "The California Story," CIA Inspector General Frederick P. Hitz reasserts CIA contentions that key figures from the crack ring did not have direct ties to the CIA and that their donations to the contra cause were relatively small. The report also denies that the CIA took any steps to protect contra-connected drug traffickers, Danilo Blandon or Norwin Meneses, key figures in Webb's series. But toward the end of the report, the CIA includes broad admissions that many of Webb's contentions were not only true, but understated the contra-cocaine connection. For instance, in his interview with the CIA, Blandon gives a detailed -- and surprising -- account about private meetings that he and Meneses had with contra military chief Enrique Bermudez, who worked directly for the CIA and ran the largest contra army known as the FDN. Prior to the Sandinista revolution in 1979, Meneses had been notorious in Nicaragua as a drug kingpin. But Bermudez still welcomed Meneses and Blandon when they stopped in Honduras in 1982 en route to Bolivia where they planned to arrange a shipment of cocaine. During that stopover, Bermudez asked for their help "in raising funds and obtaining equipment" as well as procuring weapons, the CIA report states. Blandon repeated his account, cited by Webb in the 1996 series, that Bermudez advised the two drug dealers that when it came to raising money for the contras, "the ends justify the means." Though Blandon insists that he was not sure what exactly Bermudez and the other contras knew about Meneses's cocaine operations, Blandon goes on to describe how the contras helped them continue on their travels to Bolivia. After meeting with Bermudez, contras escorted Blandon and Meneses to the airport in Tegucigalpa. They were carrying $100,000 in drug proceeds for their Bolivian drug deal, Blandon said. However, at the airport, Blandon was stopped and arrested by Honduran authorities. His $100,000 was confiscated. But the contra escorts quickly intervened to save the day. They told the Hondurans that Blandon and Meneses were contras -- and demanded that the $100,000 be returned. The Hondurans complied and the two drug dealers were able to continue their trip. In his interview with the CIA, Blandon sought to minimize the sums of drug money that went into the contra coffers. He estimated the amounts in the tens of thousands of dollars, not millions. But he acknowledged that Meneses was active in the contra support operations in California, playing the role of "personnel recruiter." In a separate interview with the CIA, Meneses confirmed his recruiting position and added that he also served on an FDN fund-raising committee. But, like Blandon, Meneses downplayed the significance of drug trafficking as a contra funding source. Meneses talked to the CIA from prison in Nicaragua where he's been held since November 1991 when Nicaraguan police arrested him on charges of narcotics trafficking. At the prison, the CIA also interviewed one of Meneses's co-conspirators, Enrique Miranda. In that interview, Miranda maintained that Meneses was more deeply involved in contra drugs than he was now letting on. Miranda said Meneses had told him that Salvadoran military aircraft would transport arms from the United States to the contras and then return with drugs to an airfield near Ft. Worth, Texas. Miranda said he personally witnessed one such shipment to the Ft. Worth area, where maintenance workers gave the drugs to Meneses's people who then drove the contraband off in vans. Miranda recalled Meneses saying that he did not stop selling drugs for the contras until 1985. The CIA received more corroboration about Meneses's contra-cocaine work from Renato Pena Cabrera, another convicted drug trafficker associated with Meneses. Pena claimed that he participated in contra-related activities in San Francisco from 1982-84 while serving simultaneously as Meneses's drug buyer in Los Angeles. "Pena says that a Colombian associate of Meneses's told Pena in 'general' terms that portions of the proceeds from the sale of the cocaine Pena brought to San Francisco were going to the contras," the CIA report states.

Mystery Drug Group

Another startling disclosure in the CIA report appears in an Oct. 22, 1982, cable from the office of the CIA's Directorate of Operations which receives information from U.S. law enforcement agencies. "There are indications of links between [a U.S. religious organization] and two Nicaraguan counter-revolutionary groups," the cable read. "These links involve an exchange in [the United States] of narcotics for arms." The cable added that the participants were planning a meeting in Costa Rica for such a deal. Initially, when the report arrived, senior CIA officials were interested. On Oct. 27, CIA headquarters asked for more information. The unnamed agency expanded on its report by telling the CIA that representatives of the FDN and another contra force, the UDN, would be meeting with several unidentified U.S. citizens. But then, the CIA reversed itself, deciding that it wanted no more information on the grounds that U.S. citizens were involved. "In light of the apparent participation of U.S. persons throughout, agree you should not pursue the matter further," headquarters wrote on Nov. 3, 1982. Two weeks later, CIA headquarters mentioned the meeting again, however. CIA officials thought it might be necessary to knock down the allegations of a guns-for-drugs deal as "misinformation." The CIA's Latin American Division responded on Nov. 18, 1982, reporting that several contra officials had gone to San Francisco for meetings with supporters. But no additional information about the scheme was found in CIA files. The CIA inspector general conducted one follow-up interview, with drug trafficker Pena. He stated that the U.S. religious organization was "an FDN political ally that provided only humanitarian aid to Nicaraguan refugees and logistical support for contra-related rallies, such as printing services and portable stages." The name of the religious organization was withheld in the publicly released version of the CIA's report. Rev. Sun Myung Moon's religious-political groups, some based in the United States, were extremely active supporting the contras in the early 1980s. Moon's organization also had close ties to the so-called "cocaine coup" government of Bolivia. In the mid-to-late 1980s, Moon's Washington Times newspaper led the attack on investigators examining contra-drug allegations. Given the Bolivian connection to the Meneses drug operation in the same time period, the possibility of a Moon link to the allegations might add credibility to the charges of a Bolvian-contra cocaine pipeline. But other Religious Right groups also were collaborating with the contras at that time, and it could not be ascertained if the CIA's reference was to a Moon organization.

Frogman Case

The CIA report responds touchily to another case where the intelligence agency discouraged a deeper probe into contra-connected drug trafficking: the so-called Frogman Case. In that case, swimmers in wet suits were caught on Jan. 17, 1983, bringing 430 pounds of cocaine ashore near San Francisco. Eventually, 50 individuals, including many Nicaraguans, were arrested. The case quickly became a potential embarrassment to the CIA when a contra political operative in Costa Rica, named Francisco Aviles Saenz, wrote to the federal court in San Francisco and argued that $36,800 seized in the case belonged to the contras. Aviles wanted the money back. The new CIA report indicates that CIA officials in Central America fretted about a follow-up plan by Frogman Case lawyers to depose Aviles and other Nicaraguans in Costa Rica. A July 30, 1984, cable from the Latin American Division expressed "concern that this kind of uncoordinated activity [i.e., the AUSA (assistant U.S. attorney) and FBI visit and depositions] could have serious implications for anti-Sandinista activities in Costa Rica and elsewhere." The CIA's lawyers next contacted the Justice Department and arranged for the Costa Rican depositions to be cancelled. "There are sufficient factual details which would cause certain damage to our image and program in Central America," CIA assistant general counsel Lee S. Strickland wrote in an Aug. 22, 1984, note. Without further ado, the $36,800 was returned to the contras. On Aug. 24, 1984, CIA headquarters explained to the Latin American Division that "in essence the United States Attorney could never disprove the defendant's allegation that his was [a contra support group] or [CIA] money. ... We can only guess at what other testimony may have been forthcoming. As matter now stands, [CIA] equities are fully protected, but [CIA's Office of General Counsel] will continue to monitor the prosecution closely so that any further disclosures or allegations by defendant or his confidants can be deflected." When word of the returned contra money surfaced in the San Francisco Examiner on March 16, 1986, the Reagan administration was in the midst of a furious political battle to convince Congress to restore CIA funding for the contra war. The last thing the White House wanted was more evidence of contra-connected drug trafficking. Within days of the newspaper story, San Francisco U.S. Attorney Joseph Russoniello stepped forward as point man for the counter-attack. In a harsh letter to the newspaper, Russoniello insisted that the return of the money was simply a budgetary decision and "had nothing to do with any claim that the funds came from the contras or belonged to the contras. ... No 'higher ups' were involved, as Congresswoman [Barbara] Boxer wrongfully surmises." It is now clear that Russoniello's protest does not square with the documentary record as compiled by the CIA's inspector general.

Not the Whole Truth

Still, the CIA's executive summary and its sweeping dismissal of Webb's series seem as disingenuous as Russoniello's letter. While the CIA touts its finding of no CIA relationship with the key cocaine traffickers, the fine print tells a very different story. Indeed, the actual records reveal a far more disturbing picture, with the contra military commander, Bermudez, in close contact with a notorious drug lord, Meneses. But Bermudez could not be questioned, since he died in a mysterious shooting in Managua after the contra war ended. The CIA also is working on a second volume of its contra-cocaine report, one that will examine even broader questions of what the CIA knew about the associations between its contra clients and the cocaine cartels. It is unclear when volume two will be made public. But the consequences of the CIA's over-stated early denials and the mainstream media's ready acceptance of the official story were devastating to Webb. Under pressure from major media outlets and conservative journalism reviews, Webb's editors backed away from the series and publicly joined in criticizing their reporter. Webb was yanked off the story and was reassigned to a suburban bureau in a move widely seen as a demotion. In December, the CIA leaked its findings while still withholding its actual report. At about the same time, Webb agreed to resign from the Mercury News. He is now out of daily journalism and working on a book.