A

Tribute to Frank Mebs

For

30 years Bill Mebs avoided talking about his

oldest brother Frank, an Army private who dies

in Vietnam when the bulldozer he was driving

rolled onto an ammunition dump and exploded.

Frank was just two weeks away from going home

to Bucks County and his death was to painful

to remember.

For

the same 30 years, Don Aird just couldn't forget

that explosion. Not the strange boom that awoke

him May 27, 1970, as he slept underneath a truck

at Fire Support Base Veghel. Not the hot orange

flashes he could feel against his face. And

certainly not the sight of bulldozer parts,

wheels, pipes, shards of metal, raining on his

battalion. “I still see the flash with my eyes

closed," he said, "It's still coming

back," I say "Here's that ammo dump

again."

Aird

didn't know Francis Martin Mebs, the 20 year

old man on the bulldozer. But he believed that

man had thwarted a fire that could have blown

away the 600 men stationed on that hill near

Hue. And he wanted so desperately to tell that

man's family. Tuesday, he did.

That

day, Bill Mebs got a letter from Aird saying

that the brother he lost died a hero.

It

was news to Mebs and his six remaining siblings,

who had long presumed that Frank Mebs' death

was just an accident they could not explain.

“I

accepted it," Bill Mebs said of his brother's

death, which was followed a year later by the

death of their grief-stricken mother. "But

I thought it was a waste, because he just got

blown up."

Aird

told the family there was more to Frank Mebs'

death. Mebs, an engineer in Company A of the

27th Engineer Battalion, was helping to contain

the fire, using his bulldozer to push dirt on

the burning heap of ammunition. He gave up his

life, but he saved others, Aird wrote.

"There

were three artillery batteries and a company

of infantry on that hill," he wrote. "I

think that if the dozer hadn't contained the

explosion, one or more of the artillery batteries

would have gone up, maybe even the whole hill."

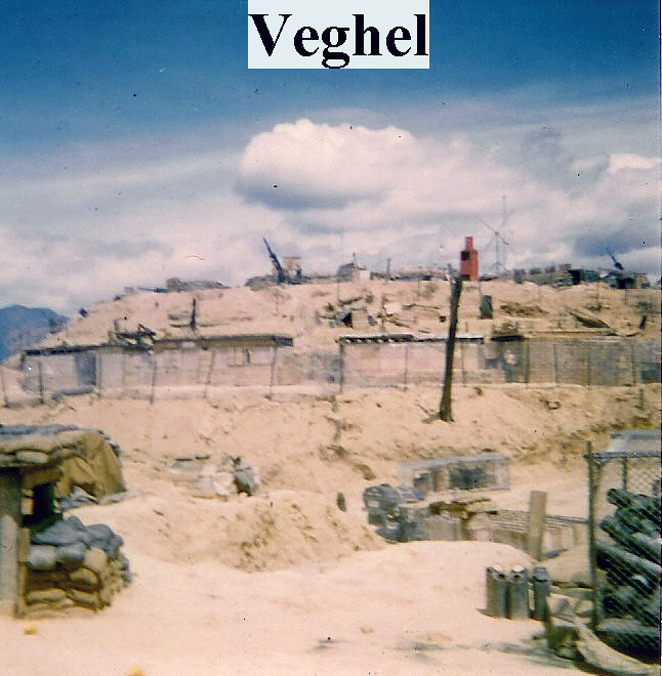

Fire

Support Base Veghel, like hundreds of others,

was set up as a warehouse of ammunition and

manpower for American forces.

Click

here for information about Fire Support

Base Veghel

Aird

had arrived that week as a member of the First

Battalion of the 83rd Artillery. Already on

the hill were another artillery battalion, a

company of infantry and Frank Mebs' engineering

battalion. Mebs was a bulldozer operator, and

a proud one, his family said. Mebs, who left

Council Rock High School in 1966 to enlist,

wrote home nearly monthly, sending dozens of

photographs of the D-7 dozer that the Army entrusted

to his care.

Fire

support bases were common enemy targets, said

William Donnelly, a historian at the U.S. Army

Center of Military History in Washington. And

around 1 a.m. on May 27, 1970, the infantry

battalion at Veghel suspected that just such

an attack was under way.

Battalion

crews fired two mortar rounds, but did not fire

them with sufficient charge to reach their target,

according to archives of an army investigation

that labeled the incident "friendly fire."

The

rounds instead fell short and ignited an ammunition

dump on the hill.

The

engineering battalion leaped to action, trying

to contain the fire, according to documents

filed at the National Archives. Among them were

Frank Mebs and his bulldozer.

Twenty

minutes after the fire started raging, the shed

exploded, killing Mebs and Sgt Edward M. Miller,

who Aird said was hit by a piece of the bulldozer

debris.

Aird

heard the pieces hit the truck he was under,

and rushed to slide from under it to see what

had happened.

Everyone

around him was talking about the man on the

bulldozer.

The

potential for catastrophe was there. Aird's

artillery battalion alone had enough gunpowder

for 160 rounds for each of four guns. For one

type of gun, a round equaled 90 pounds of powder.

That alone had a "killing radius"

of 120 meters, or about 130 yards, Aird said.

"I

think this guy might have saved our lives,"

Aird, now 56, said last week in a telephone

interview from his Minneapolis home.

The

survivors decided they would find out the man's

name, his rank, and who his family was. But

they got sidetracked by the war, by the Army's

sealed records, and by distance.

The

Mebs family would know few of the details that

Aird would share three decades later.

Fred

Mebs remembers that May day 1970 when two Army

officers walked into the family's home in Newtown

Borough.

The

13 year old, who was in the front yard, leaned

toward the door to hear. They were talking about

Frank.

"They

told my mom and dad he was blown up on a dozer,"

Fred Mebs, 44, said last week.

Their

mother, Dorothy Elizabeth Mebs, died of an aneurysm

a year later on the anniversary of Frank's death.

The

family did not speak publicly about the death.

They kept Frank Mebs' Vietnam photographs. They

had an artist make oil paintings, one of which

hangs at Council Rock High School on a memorial

wall.

Each

year, the school commemorates students who fell

in the line of duty, said William Mauro, high

school assistant principal and Frank Mebs' gym

teacher. "The Mebses come every year,"

he said.

All

those years, Don Aird was searching. Without

a name to go on, getting information was very

hard. Aird tried the obvious routes: The Veterans

Administration, the Army.

"They

bump you from office to office until they run

you into a complete circle and then you get

so frustrated that you quit," said Aird,

now a public relations officer at the Minneapolis

office of the U.S. food and Drug Administration.

The

Internet eventually helped Aird do in weeks

what he could not for decades: reach veterans

across the country in discussion groups.

Aird

posted inquiries on several veterans Web sites.

One response pointed him in the right direction.

Aird

was told that the man operating a bulldozer

must have been an engineer, then the Internet

source located the only engineer he could find

who died on that date and in that area.

When

Aird got Mebs' name, he started calling all

the Mebses he could find. The first call was

July 5, to Deanna Mebs, ex-wife of Frank Mebs'

brother Martin. He left a message on the machine

saying he was looking for the family of Frank

Mebs, but left no number.

He

called Bill Mebs' home July7, asking for the

family's address. Bill Mebs' 15 year old daughter

dutifully dispensed it to the stranger, initially

to her parents' dismay.

Finally

on Tuesday, the letter ame. It told a tale that

the Mebses are still too shocked to absorb.

"I

was crying until the end," Bill Mebs said.

Fred

Mebs has yet to read it, his hands shake when

he holds Aird's letter.

Fred

sat in Bill's kitchen last week, while Fred's

fiancée, Midge Grabowski, helped him

manage the bittersweet tears.

"Now

the family knows that his death was due to a

hero's effort," Grabowski said. "And

not just...." She paused for words. "Blown

up." Bill said.

To view the original

newspaper clippings just click on the pictures

below to enlarge

|