![]()

Treatment and Diagnosis:

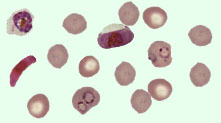

For treatment, chloroquine sensitive malaria is controlled by intravenous chloroquine. For drug resistant forms, quinine dihydrochloride combined with a dose of tetracycline antibiotics should be used (omit tetracyclines in pregnant women and children under one year old). Quinine may also be infused. The most important element in the diagnosis of malaria is a high level of suspicion (15). As malarial distribution is patchy, a geographical and travel history indicating exposure is important - though the possibility of induced malaria (through contaminated needles or transfusions) cannot be overlooked. The clinical symptoms may be confused with a number of other diseases, and this will be dealt with in a subsequent section. In the majority of cases, microscopic examination of thick and thin films of the peripheral blood will reveal malaria parasites - though thick films are more useful. Most patients with severe malaria have significant hyperparasitaemia, unless they have already taken antimalarial drugs. The presence of malaria pigment in monocytes is also a useful diagnostic indicator in malaria, especially in anaemic children and in suspected severe malaria with absent parasitaemia due to the synchronous nature of infection. It is important to treat promptly on diagnosis to avoid complications. The diagram below shows how some of the stages of P. falciparum appear in thick blood films.

- Trophozoites (small, numerous, fine cytoplasm, coarse pigment grains)

- Schizonts (small, compact, few in number, with a dark, pigmented mass of 12-30+ merozoites)

- Gametocytes (rounded or banana shapes, uncommon)

Differential Diagnosis:

Failure of physicians to consider the diagnosis of malaria in a person returning from an endemic area is a frequent cause of morbidity and mortality (17). Errors in diagnosis can result from failure to do a malarial blood film, failure to take a travel history, misjudgement of severity, faulty parasitological diagnosis and laboratory management, missed hypoglycaemia, failure to carry out opthalmoscopic examination for retinal haemorrhages, or misdiagnosis.Malaria may be misdiagnosed as a number of other conditions, most importantly meningitis, typhoid fever and septicaemia. Other differential diagnoses include influenza, hepatitis, scrub typhus, all types of viral encephalitis, gastro-enteritis, and haemorrhagic fevers. It is easy to see why so many conditions may be confused with malaria, given the wide range of symptoms and complications already listed in the section on pathogenesis.

Treatment and Management:

A number of measures should be applied to all patients with clinically diagnosed or suspected severe malaria. Antimalarial chemotherapy must be given paraenterally (intravenously or intramuscularly). Oral treatment should be substituted as soon as possible. It is necessary to eliminate other possible causes of coma in the unconscious patient, so lumbar puncture should be carried out. The patient should be monitored for hypoglycaemia, and glucose given if necessary. The rate of infusion of I.V. fluids should be carefully monitored, as should the urine production. High body temperatures should be reduced by antipyretics or sponging.The administration of a prophylactic anticonvulsant such as phenobarbital sodium (10-15 mg/kg body weight, intramuscularly) is advised in severe malaria. Regular monitoring is essential, and the patient should be nursed on his/her side to avoid the risk of aspiration of fluid. The patient must not be allowed to lie in a wet bed, and should be turned every couple of hours. The airways must be kept open, and if rectal temperature (monitored every 4 hours for at least the first 48 hours after infection) rises above 39°C then paracetamol may be given, and sponging initiated. Drugs which increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding such as aspirin or corticosteroids must be avoided (15).

The drugs currently appropriate for the treatment of malaria vary according to the type of malaria. For chloroquine sensitive malaria, administer 10mg base/kg of body weight in isotonic fluid by constant rate I.V. infusion over 8 hours followed by 15mg base/kg body weight given over the next 24 hours. Alternatively, chloroquine 5mg base/kg body weight in isotonic fluid by constant rate IV infusion over 6 hours may be given, repeated every 6 hours for a total of 5 doses. If IV infusion is not possible, give chloroquine 3.5mg base/kg every 6 hours intramuscularly until the total dose is 25mg base/kg. Oral therapy should be initiated as soon as the patient can swallow (15).

For chloroquine resistant malaria (largely diagnosed by the geographical area in which the malaria was contracted), a loading dose of 20mg quinine dihydrochloride salt/kg body weight should be infused over 4 hours, in 5% dextrose saline. An infusion pump may be used to introduce 7mg salt/kg over 30 minutes, if available. Next a maintenance dose of quinine 10mg salt/kg in dextrose saline should be administered 12 hours after the loading dose (no delay is needed if an infusion pump was used). The maintenance dose must be repeated every 8-12 hours until the patient can take oral therapy.

Alternatively, quinidine gluconate (only used if paraenteral quinine is unavailable) may be infused as a loading dose of 15mg base/kg body weight over 4 hours. The maintenance dose is 7.5mg base/kg repeated every 8 hours until oral medication can be taken. In all cases, loading doses are not required if the patient has taken quinine or quinidine or mefloquine in the preceding 7 days. If patients require more than 48 hours paraenteral therapy, then the maintenance doses of quinine and quinidine must be reduced by one third to one half (15).

Oral therapy depends on parasite sensitivity and drug availability. Quinine tablets, 10mg/kg, every 8 hours to complete 7 days treatment are a common treatment. Alternatively 15mg/kg mefloquine may be given in 2 doses 12 hours apart may be given (but not to pregnant women). A recent study (18) suggests that higher than normal (i.e. 25 mg/kg as opposed to 15mg/kg) doses of mefloquine are considerably more effective - although unpleasant side effects such as dizziness, anorexia over the 7 days after treatment, and vomiting which may necessitate re-treatment, may be observed. Another useful oral antimalarial drug is halofantrine, 8mg base/kg every 6 hours for three doses, although this must not be given to pregnant women. Where there is significant quinine resistance (as in malaria contracted in Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam) an oral dose of tetracyclines, 250mg four times a day, for seven days of treatment should be given. It is dangerous to give IV tetracyclines, and they should not be given to pregnant women or children under 8 years of age (15).

All of the drugs mentioned above have certain problems associated with them. Quinine, the drug of choice for severe malaria, may cause serious hypoglycaemia, and quinine poisoning is treated with oral activated charcoal. Chloroquine, still the most widely prescribed antimalarial in the tropics, and, though providing symptomatic relief, does cause nausea, blurred vision, hypotension and, in chloroquine poisoning, coma and dysrhythmias. Mefloquine resembles quinine in structure and remains generally effective - it may, however, cause nausea and diarrhoea. Halofantrine is effective against resistant falciparum, but has poor bioavailability and may not be used in pregnant women. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine is used only if chloroquine and quinine are not available, as there is widespread resistance to it. Quinghaosu, an artemisnin compound currently undergoing clinical trials seems effective, with rapid action and few side effects. It is not generally available, however. Even the newest drugs are not flawless; the side-effects of Larium caused an uproar.

The use of drugs such as mefloquine and chloroquine in the prophylactic role appears somewhat questionable, given the deteriorating global resistance situation, and the NHS no longer prescribes prophylactic antimalarials. Perhaps insecticide impregnated mosquito nets and insect repellent creams are the best prophylaxis for a traveller, especially due to the problems of unpleasant side effects and non compliance. Indeed, it seems that the initial widespread prophylactic use of the now outdated antimalarials was responsible for the rise of resistance in the first place (19). This is a cautionary indicator for how we use our new drugs such as artemisnins in the field. It seems that many travellers still take antimalarials in the prophylactic role, however.

![]()

Webmaster : Mr. Kulachat Sae-Jang

4436692 MTMT/D

Medical Technology, Mahidol University

E-mail address : oadworld@yahoo.com