--by Karen MacPherson

(Salina Journal Sept. 14, 1995: A6)

|

"Meet the

real Pocahontas; she wore a tall hat" --by Karen MacPherson (Salina Journal Sept. 14, 1995: A6) |

|

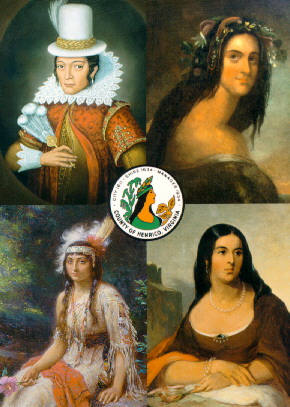

Washington (Scripts Howard News Service) She doesn't look a thing like the movie glossies. Her hair doesn't flow down her back; it's curled up under a rather ridiculously tall hat. She doesn't have the wide-eyed, innocent stare of the ingenue; instead she gazes steadily and calmly at the world. And her garment isn't a leather shift that highlights her ample curves. Instead, she's literally up to her neck in lace and stiff fabric robes, which nearly camouflage her gender.

Meet the real Pocahontas, on display in the an oil painting at the Smithsonian Institution's nathional Portrait Gallery.

"It's the closest we have to a life portrait of Pocahontas," says Ann Wagner, a curatorial assistant in the gallery's department of prints and drawings.

Young visitors to the gallery this summer, particularly those who have seen the new Disney movie "Pocahontas", are surprised at how the Indian "princess" actually looked.

"Children see it and they say, 'That doesn't look like Pocahontas," says Ellen Miles, the gallery's curator of painting and sculpture. "But we've had a lot more interest in the painting. It's wonderful"

The oil painting on display at the National Portrait Gallery actually is a copy of the original engraving done of Pocahontas in 1616 by Dutch artist Simon Van de Passe. Van de passe's engraving was done for a book featuring engraved portraits of kings and other important people in England.

The National Portrait Gallery also owns a copy of the Van de Passe engraving but it can be displayed only sparingly because of its fragility.

The engraving was done when Pocahontas sailed to England in 1615 with her English husband, John Rolfe, whom she met in Jamestown, Va., after being captured by settlers. They were accompanied in their journey by their baby son, Thomas, and 10 or 12 American Indians.

In England, Pocahontas was presented at court and widely feted. She also had an emotional reunion with Captain John Smith, whose life she saved in 1607 after he had been seized by the followers of Chief Powhatan of Virginia -- Pocahontas' father.

In the engraving done while Pocahontas was in England, she is wearing clothes typically worn by well-off English women of that time: a tall hat and a mantle -- a loose brocade cloak -- topped with a high lace colllar.

She's holding a feathered fan, possibly composed of ostrich feathers, also a typical touch of the time.

"She was presented at court and to English society as visiting royalty, and she dressed in appropriate European style," says Waqgner.

It's difficult to read her expression in the painting, however; something that's not unusual for the time, says Miles. "Paintings of that period don't usually record emotions in the way that we're used to. The idea was to represent the character of the person."

An inscription on the engraving calls Pocahontas by the English name she took, Rebecca, and notes her Indian nickname, "Matoaka," which means "playful," says Wagner.

The inscription stresses that Pocahontas was "converted and baptized in the Christian faith," a point of pride to the American settler community.

"she was celebrated in England because she had become a convert to christianity, and also because she was an American," Miles says.

Pocohontas never made it back home to America, however. She died at age 21 and is buried in the chancel of St. George's Church in the Gravesend area of London.

Have questions or comments? Email Jay Edwards

Back to the Class Page