"The first building material of the universe was silence."

-- Swami Veda Bharati

"Spore of mountains has fallen there."

-- Henry David Thoreau, journal, October 1857

Saturn Day

Up before dawn to an alarm, I call for a cab, ride to the airport, fly to New York JFK, catch a tram to rental car offices, pick up a car Iíd reserved-- a Dodge Neon-- and head north sometime before noon, across the Whitestone Bridge which one pays $4 for the privilege of crossing.

What tolls do we less consciously pay?

The road is an artery and I am a corpuscle.

These words are a map I have drawn.

Welcome to Connecticut. From Norwalk I drive north to the Merritt Parkway from which commercial vehicles are banned, stop in Hamden around 2 p.m. to empty my bladder and eat a bite, then make my way north to Mass.

Traffic halts for a while on the Wilbur Cross Highway, then creeps along. (Turns out a car has been driven off the side of the road. The left-hand two lanes are taken up by a fire truck, highway patrol cars, wrecker, and the crashed vehicle.)

I detour off the expressway on U.S. 20 south of Worcester, intending to find the town of Dodge. Itís supposed to be near Texas, Mass. Driving through Texas, I see no sign of Dodge, but by taking U.S. 20 Iíve avoided a short stretch of toll road.

Next pit stop: a service station outside West Acton, a town west of Concord. Iíve turned off with the idea of making a brief foray into Concord, then think better of it when the station appears right beyond the end of the ramp. I pump gas, purchase a yogurt beverage of dubious merit, and continue on the way.

Interstate 95 passes through the southeast corner of New Hampshire. Here I stop at a visitor center, setting foot in the state for the first time in my life, compelled in part by a snowy blanket of flowers I noticed along the road. Spring beauties? (Yes and no: Theyíre wild strawberries.)

Tired and hungry, I stop again in Portland, Maine, pulling up to a place called Beckyís Diner, harborside, a bustling joint where people eat platters of fish, mashed potatoes, and orange squash. I sit at the counter, having just ordered what may be the priciest item on the menu, a lobster roll, as a co-worker had advised me to consider. Cold lobster with mayo on a hot-dog bun, served with fries and cole slaw. Junk food. But with an empty stomach, it goes down happily. Hunger is the best salsa, Cervantes wrote in Spanish.

Traveling with her family, my friend Margaret Miles visited the 48 continental states by age 7 or 9. Amazing, yes? No wonder she knows wanderlust.

After dinner I cross the street to a gas station/market; purchase a Portland, Maine, postcard; address it to someone who lives in Portland, Oregon; then head back to the northbound freeway, following a car labeled with a small round Found Magazine bumper sticker.

Road weary, I stop for the night in South Freeport, having seen signs for motels. Passing large chain establishments, the parking lots of which are almost empty, I turn into a mom and pop place called the Dutch Lighthouse Motel, with colorfully painted cabins as well as a small motel and swimming pool. Here, as I wait for a woman to get off the phone, I look around at a waiting room that includes an old wooden phone booth and a nickel Coke machine. Hereís a framed photo of the motel and cabins dating from over seventy years ago, well before chain motels existed.

For $35 I rent a cabin (an arrangement that includes continental breakfast in the morning), ask about the location of a grocery and a place to mail a postcard, then go to a nearby supermarket for provisions.

After that itís hand laundry time. And bed.

Sun Day

The pair of clean underwear I draped on a heater last night discolored and thinned where it touched hot metal, giving me a memento.

The freeway carried traffic past here all night long, it seemed. Once upon a time Highway 1 must have been quiet after dark.

In season this cabin rents for $150 daily, according to a sign on the inside of the door.

Breakfast: cold cereal, juice, the first banana Iíve eaten since maybe last September when I visited my mother, and a Danish. (Anglo-American Eats Danish in Dutch Motel.)

The waiting room/breakfast area has bookshelves containing a 50th anniversary edition of the complete Petersonís guides, with hard covers and gilt-edged pages. I didnít know all of these titles existed. Moths (a big volume). Southeastern Seashores. Advanced Birding. Western Forests. Animal Tracks, by Olaus Murie (including scat and marks on trees). Geology. Ferns. Western Butterflies. Eastern Butterflies. Atlantic Seashore. Birds of Texas. Atlantic Coast Fishes. Bird Tracks of the Pacific Coast. (I made up the last one.)

A boy named Richard tells me the long-haired tabby is named Casco. He doesnít add, "after the bay here."

Why this infatuation with names? And why not name children after bodies of water? A colleague and his wife have named their new son Everett Huckleberry, recalling Everett Ruess, Huck Finn, and the berry-loving Henry David Thoreau all at once. May he thrive.

This recalls Ralph Waldo Emersonís eulogy for Thoreau. Although deeply understanding, it laments what Emerson saw as lack of ambition in his younger friend and suggests that Thoreau wasted some of his life playing. "[I]nstead of engineering for all America, he was captain of the huckleberry party."

Imagine that.

A male goldfinch sings. But my left eye is so watery and irritated I can hardly see it.

The new Maine license plate has MAINE at the top and LOBSTER at the bottom, with an illustration of a lobster on the left side.

Iím intrigued by tidal pools. They look like bogs (and are). When I saw them at dusk they were nearly dry and marked by sinuous channels. Earth art, muddy and grassy. (Are estuaries an eastern thing?)

Time for a little detour to the Freeport town wharf. In South Freeport a big granite rock looms over one corner of the intersection of Main Street and Something or Other. And hereís a quintessential New England white mansion, small but royal, with a weeping willow in front.

The L.L. Bean flagship store in Freeport is open 24-7, 365 days a year, wrongly.

Traveling on U.S. 1 for a while instead of the expressway, I find itís slow going, full of Sunday drivers.

Sign near Belfast: FUDGE MOCCASINS.

North of Bath, less leaves appear on trees. Spring hasnít arrived here yet.

Iíve seen four Thai restaurants in Maine so far.

Late morning: Bucksport. Long narrow bridge over the Penobscot River near its mouth.

Detour or pilgrimage? Getting to Forest Farm requires many turns. First south from U.S. 1 toward Blue Hill. Another right on Rte. 15, then south again at the Penobscot Town Hall to Brooksville. Then another right, following signs for the Holbrook Island Sanctuary. Another right on Cape Rosier Road, past the turn-off to the sanctuary, then still another right at the Rainbow/Rosier grange hall. At last off the beaten path, after two miles, take a left at the T intersection onto a paved road thatís only about as wide as a driveway, and follow it two miles past a burnt field of rocks, past a cove on the right, to another smaller cove.

Land on the left, sea on the right. Quiet and calm.

Helen and Scott Nearing moved to Maine after homesteading nearly thirty years in Vermont. Theyíd moved to rural southern Vermont from New York City in late 1932, built a stone house without blueprints, and developed a sustainable farm, making maple sugar for a living, growing their own food, and later writing about it in Living the Good Life, first published in 1954, a book Joe Hart says led his parents to purchase land on the Pigeon River in northern Minnesota which is why he and his siblings grew up in that rustic place.

When Vermont felt crowded with too many tourists and visitors, the Nearings went north to Penobscot Bay in 1952, moving into a wooden house (on about 140 acres of land) and turning to blueberry cultivation to pay expenses. There, once again, the Nearings used readily available stone to build. Their first project: A wall enclosing a hundred square foot garden, five feet above ground and three or four feet below, "a spare time job"--according to Helen in her book Loving and Leaving the Good Life--that took fourteen years to finish.

In the 70s the Nearings sold off all but five acres of their land at the same price theyíd paid for it two decades before ($33/acre) and began clearing a site about a quarter mile from the house where theyíd been living. First to be constructed was an outhouse, completed in 1973 (the year Scott turned 90), then a 22í x 50í garage/workshop, and then a new house, again designed by Helen, inspired by Swiss chalets, and modeled after their Vermont dwelling. Helen writes that she chose its location overlooking the bay and laid every stone in it herself, "allowing Scott to hand me shovels full of concrete he mixed in a wheelbarrow." The 35í x 53í house was completed in 1979. The Nearings moved in and lived there the rest of their days. (Scott died in 1983 at just past 100, having decided to stop eating. Helen died in 1995 at 91.)

But they are still alive in many ways.

The house is like the canyons of southern Utah: cool and dark in places and at times, yet bright where the sun comes through a skylight, and warm with spirit. The Nearingsí library is still shelved around their living room, and other belongings are at hand--musical instruments, wooden shoes, sundry tools-- ready to be used. The place smells of wood and stone and leather, the latter from book bindings. Here are the complete works of Dickens, Thoreauís journals (penciled with underlining and exclamation marks), texts on theosophy and religion, works about death, radical politics, and UFOs, the latter an interest of Helenís. Here are Emerson, Brecht, Dostoevsky, and Hamsun, shoulder to shoulder with Krishnamurti, Whitman, Twain, and Lewis Carroll. Books filled with clippings, books that have been used.

There is a strong sense of intention here.

Tucked between two Thoreau volumes is a folder of Helenís notes on the Concordianís life, along with some reviews of Walden. A note on the folder says Helen was keynote speaker at the July 1994 Thoreau Society annual meeting.

In early 1921, seventeen-year-old Helen Knothe was taken by a teacher to a gathering at Scott Nearingís home. Both were living in Ridgewood, New Jersey, where Helen attended high school. At that time, the 38-year-old Nearing was an author and former professor whose radical views had lost him jobs at the University of Pennsylvania and University of Toledo. Indicted in 1917 for allegedly obstructing military recruitment, a charge based on his book The Great Madness, Nearing was acquitted after a jury trial, but never again hired for a college teaching position.

In July of that year, having graduated, Helen went to Europe, on track to become a concert violinist. There she met young Jiddu Krishnamurti with whom she became intimately linked for several years, traveling throughout Europe, India, and Australia. But that life was not to continue. Returning to New Jersey after years abroad, Helen struggled during what she later called a waiting period in her life. Then she called Scott Nearing to ask him to speak to a club of which her father was president. And she liked the sound of his voice.

Scott Nearing was 45, Helen Knothe was 24. So what?

And Scottís birthday was August 6.

In the kitchen: wooden tuns, tin canisters, baskets.

Outside: fruit trees (apple and pear). A greenhouse burgeoning with greens already in May. The farmstead is now maintained as the Good Life Center, with a young couple of resident stewards who garden, conduct tours for students, show visitors around, and sell copies of the Nearingsí books.

For water thereís a drilled well. For heat: Two wood stoves. Forthcoming: solar panels to supply the minimal electricity needed.

A cool breeze blows in from Orr Cove. The sky is blue. Yellow-rumped warblers flit about in trees near the tidal flat. Purple-shelled mussels are stranded on the shore at low tide.

Students visiting the Good Life Center departed a while ago in two vans labeled Bowdoin College. Thatís where 1984 Olympic marathon gold medalist Joan Benoit went to school, I think. Bo-DOYNE? BAO-doyne? Bo-do-in? I do not know.

I have a strong urge to ask if I can camp out for a night or two in the wooden yurt built by William Coperthwaite, partly so I might peruse the library more carefully, but also so I might lend a hand in the garden and soak in more of this beautiful calm. But thereís a mountain calling me from further north.

I have a strong urge to ask if I can camp out for a night or two in the wooden yurt built by William Coperthwaite, partly so I might peruse the library more carefully, but also so I might lend a hand in the garden and soak in more of this beautiful calm. But thereís a mountain calling me from further north.

Driving out I pass the biggest field of rocks I can recall seeing. A rock farm.

I retrace my route back to Bucksport, then head north to Bangor (it doesnít rhyme with "hanger"-- instead, say BANG-gore) where I rejoin the interstate and go about sixty miles further in that direction, then exit and head west to Millinockett. A road sign gives a radio frequency for information about Baxter State Park, so I tune in and learn, from a scratchy recorded voice, that the park is closed to camping from April 1 to May 15, and that Ktaadn is usually not "open" till Memorial Day. As if humans can open or close a mountain.

Nevertheless, I drive on, scouting, another eight miles or so northeast of town, past lakes and views of an overlooming rock, past a grazing moose, to a park entrance that is unattended. I get out and look around, then continue on toward the Abol Campground from which the shortest, steepest trail to Ktaadn begins.

The road to the campground is closed by a gate, so I turn off a spur heading the other direction and park at the Abol Beach picnic area. No humans in sight, but plenty of insects. I walk around for a while, figuring Iíll come back here to park in the morning and hike to the trailhead. Itís about three miles away via the closed road. Can I tramp there--and up and down a mountain--and back in a day?

Driving off, after a mile or so, a turnout catches my attention. I brake and pull into a small parking area. What is this place? I get out and walk down a trail toward a lake. Hello. Here are several lean-tos situated on a lovely shore. A perfect place to camp. Why not? After sitting here a while, enjoying the quiet, I realize thereís no driving back to Millinocket today, and walk back to my car for a sleeping bag.

Itís windy here. No black flies on this point near the water. (Many swarm up the hill where the car is parked.) Bright late afternoon sun reflects on the lake. Did Thoreau paddle past the point? Possibly. Did he listen to the great-grandmother of this wind?

Itís windy here. No black flies on this point near the water. (Many swarm up the hill where the car is parked.) Bright late afternoon sun reflects on the lake. Did Thoreau paddle past the point? Possibly. Did he listen to the great-grandmother of this wind?

This would be a fine place to die. In other words, itís a good place to live. The moose must know this better than I. As does this ant.

Back in Minnesota itís late spring, fast becoming summer. Here itís late winter, in no hurry to become full-fledged spring. In blue sky a wisp of white cloud moves from the west. A forest of green lies across shimmering blue-brown water. I feel at home.

I exaggerate. It is spring here. Thrushes sing at dusk. Earlier a kingfisher went past, sounding like a wind-up toy.

Are those ducks I hear now? It sounds like a muffled voice over a scratchy loud speaker.

A raucous crow flies over. What is it celebrating? Everything.

A ring-necked duck and drake swim by. Sound of water rushing: Across the lake two loon missiles fly.

Spring peepers start their peeping, then stop after a minute. Uphill the thrush sings its timeless liquid panpipe notes.

Once again, ecstasy and sobriety at once. Exhilaration and calm.

I am an exhile.

"You are once of the most calming and inviting people I have ever met." Deeply sobering words, no?

A few shirred clouds drift on the western horizon, violet and pink. A fish jumps. Two loons swim past. A tiny moth wobbles by. Bon voyage.

An entirely human world would be insanitary. Alone is an oxymoron.

Leslie Powell, editor of The Interesting Times, asserts that nothing in the world is unnatural. (Naturally sheíd say that.)

A bright planet appears in the west. One great blue heron soars high, black in the twilight, its shape unmistakable. The moth wobbles back the other direction. Will it reproduce or be someoneís meal? Yes.

Darker and chillier outside, but warm at heart.

Tonight we live.

Peeping frogs again--they seem to echo, sounding on opposite shores.

Up there: First star, or second planet?

I wouldnít be surprised to see a deer swim past.

No one knows Iím here. Not even me.

I fall asleep to the keening of loons.

Moon Day

Sometime during the night I awake to the sound of rustling outside. What is it? A four-legged one. I tell it to go away, make a noise, and hear it scurry off. Later I awake again and realize what I hear is particularly a scraping noise. In fact, the sound of my walking stick being pushed around the ground. At some point I realize the stick must be salty, coming as it did from Penobscot Bay, and some animal is now licking it avidly.

First light. The moon appears in the lake, floating.

First light. The moon appears in the lake, floating.

A thrush calls. Mist rises from the water. A white-throated sparrow sings.

Iím off on a trail. Instead of walking three miles along a gravel road, Iím hiking beside Abol Stream, as if I know what Iím doing. In a mile or so, the path connects with the Appalachian Trail where a map is posted. If I head due north on a trail marked "BLUEBERRY LEDGES" I should meet the so-called tote road from which I can walk back east to Abol Campground and the Ktaadn trailhead.

Itís a nice hike, much of it uphill, and Iím accompanied by the singing of yellow warblers and black-throated greens. Theyíre so high up in the treetops that theyíre difficult to spot.

What in blue blazes was that? A partridge just flew off, I guess. Back in Minnesota Iíd called it a grouse.

Squeaky gate bird: black and white warbler.

Itís sometimes disheartening when the trail turns away from the goal.

At last I reach the road. Iíve hiked over four miles--probably closer to six--and still havenít reached the trailhead. Where am I? Here by the side of the road is a five- or six-inch layer of ice, parallel to the ground but well above it, through which the trunks of small trees poke. What season is this?

An ovenbird calls. (Why are they called ovenbirds and not teacherbirds?)

And this: Beer beer beer beer BEEZ! A black-throated blue?

And: Pleased pleased pleased to meetcha. Chestnut-sided.

No time to dawdle, nor to take notes. Iím climbing now. See that rocky promontory way past the trees? Up there and beyond.

I want to know the high and the low. Hereís the lowdown: a single purple trillium blossom nestled on the ground (T. erectum).

A trail sign at Abol Campground says itís roughly an eight hour climb to the peak and back. Iím on my way. Up along a running stream that covers all but the largest rocks. Up over bigger boulders still. Up relentlessly through sprucy woods till the trees thin and I can see a rocky route up the steep mountainside.

Now itís one hand over the other, clambering. Sometimes with feet on one side of a rocky wedge, hands on the other, using the body as a lever. Up and up, at last daring to look back--and down the rock slide Iíve been climbing, a curvy path of white and yellow granite disappearing below into dark green. The sensation is disorienting. Where am I, relative to flat land? At what angle am I traveling? Shouldnít I be falling?

Steeper and steeper. No thought of turning back. Infinitesimally closer and closer to the rim.

Thoreau on Ktaadn: "I looked with awe at the ground I trod on, to see what Powers had made there, the form and fashion and material of their work.... Here was no [oneís] garden, but the unhandselled globe.... I stood in awe of my body, this matter to which I am bound.... Talk of mysteries! --Think of our life in nature,--daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,--rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?"

Thoreau on Ktaadn: "I looked with awe at the ground I trod on, to see what Powers had made there, the form and fashion and material of their work.... Here was no [oneís] garden, but the unhandselled globe.... I stood in awe of my body, this matter to which I am bound.... Talk of mysteries! --Think of our life in nature,--daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,--rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?"

At last over the rim to an otherworld--a flat area, perhaps a mile and a half in diameter, strewn with green-lichen-covered rocks. A feeling of relief and mild euphoria comes, but passes. Itís evident that the peak is not at hand after all. Climbing is an exercise in faith.

A sign marks THOREAUíS SPRING, though the author never set foot on this spot. In 1846 Thoreau climbed a route of his own making, instead of following a tried way, and didnít make it this far. Here the white-blazed Appalachian Trail from the southwest and another trail from the northwest join the Abol Slide route and the three continue as one to Baxter Peak which the sign says is 1.0 miles away. The .0 suggests thereís something immeasurable beyond.

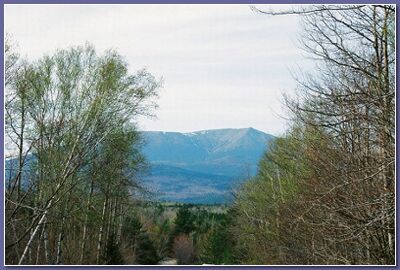

Not much time to linger here. Ice surrounds a few of the rocks. I don mittens, stocking cap and jacket, and go on. The view over the curving rim looks down at lower mountain tops (dark green) and up at sky (blue streaked with white haze). Walking from rock to rock, as if in a stream (if not a dream), I reach the next climbing stage, then sense no time passing as I practically levitate, adrenaline overriding fatigue, and reach a blustery pinnacle, beyond which only sky continues.

Ktaadn rises 5267 feet above sea level, and the climb up Abol Slide represents an elevation gain of 4000 feet in three miles.

The winds whips wildly. On a scrap of paper from my pocket I scrawl a few words, barely legible: "Cold! Windy! [Something or other] green rock."

Thereís snow up here, damp enough from the sunís rays that I make three snowballs and add them to the top of a tall cairn that points to the Knife Edge, a narrow jagged way across to a somewhat lower peak, Pamola.

A raven drifts by at the level of my eye, checking out the human visitor.

A sign at the peak spells the mountainís name KATAHDIN, northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. The distance to Spring Mountain, Georgia, has been obliterated. So is all distance obliterated here. What does it matter that the Abol Slide trail is a 7.6 mile round trip when most of it is a rugged climb?

A sign at the peak spells the mountainís name KATAHDIN, northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. The distance to Spring Mountain, Georgia, has been obliterated. So is all distance obliterated here. What does it matter that the Abol Slide trail is a 7.6 mile round trip when most of it is a rugged climb?

All the way back down I remind myself to take care where I place my next step. My limbs are weary and maybe my mind is too. I tell myself to test weight on my walking stick before I move a foot. Even so I tumble once or twice, leaving a bit of myself on the rock. If Iím going to fall, I want to arrange in advance for it to be a short one.

Thereís no shortfall at all in Ktaadnís impression on me. I sit for a while, as I watch dark clouds forming below to the south from the direction Iím returning, then take out my last food and swill some water. Sensing eyes upon me, I turn and see a gray jay watching from a nearby branch. (Iím back below the tree line.) Then it flies even nearer. Foolishly, I hold out a bit of food on my bare hand and the jay flies toward me. I toss the ort on the ground where the jay snatches it quickly, and retreats. Then I pull on a mitten and put another bit of food in my hand, hold it down at the level of my food. The jay hops over, looks at me, snatches the food, and hurries away. Thatís enough of that. Who am I fooling?

I continue down, climbing, climbing, not looking back. The dark clouds begin to spit rain. Then Iím back in the forest, still dropping in elevation, but walking again, along rocks that follow streams. Hiking forever it seems, my feet a little swollen. This very stone on which I step is Ktaadn to an ant.

I continue down, climbing, climbing, not looking back. The dark clouds begin to spit rain. Then Iím back in the forest, still dropping in elevation, but walking again, along rocks that follow streams. Hiking forever it seems, my feet a little swollen. This very stone on which I step is Ktaadn to an ant.

Other animals dwell here, too. Watching beside the path: A snowshoe hare, so named for its huge feet, in between its winter color (white) and summer (tawny brown).

At least I reach Abol Campground where I hear a human voice or two and continue on without stopping, back on the road, heading toward Abol Beach, still several miles away.

I sit down for a minute to drink my water. Then I hear the sound of a motor vehicle behind me, and turn to see a pick-up. It stops and the driver --a park ranger--asks if I want a ride. Iím happy enough to jump in the back, then we speed down the bumpy road, leaving a wake of dust. I open my mouth slightly so my teeth arenít jarred by the rough ride.

Back at my car, I hop out and give thanks. "How was the mountain today?," the ranger asks. "Was there was snow at the top?" And now heís on his way. The sky opens up and it really begins to rain. I think about going into town and getting a shower and bed, but the notion passes when I pull off at the place I parked last night. Itís such a perfect spot.

The rain eases for a spell, and I haul my sleeping bag down to the lean-to again. There I sit on a log under the shelterís vestibule, drinking water and watching as raindrops fall gently into the lake, making small white circles that disappear, sounding quiet notes that coalesce into a beautiful symphony.

My brain is empty.

Two loons swim past. One turns its head 180 degrees, prodding with its bill. Parasites? It flaps its wings.

A mosquito visits me. Thrush panpipes sound from somewhere on the hill. A ring-neck duck and its mate swim past. The drake has a black scallop on its side above a white belly, something like a saddle shoe.

Hank! hank! hank! Nuthatch.

Hooo hoo-hoo hoo. Hooo hoo-hoo hoo. Great-horned owl.

Hello, my friends, and good night. Falling asleep to the sounds of birds and water. The rain in Maine stays mainly in the brain.

Tiwís Day

Awake at first light, and happily so. The rain has ceased. I find Iíve been vandalized, though: The ziplock bag in which I carelessly put an empty food wrapper has two holes chewed in it. Later I discover holes gnawed in a shirt Iíd hung to dry. The salt from my sweat was alluring.

At 6:26 a.m. I sit in the Appalachian Trail Cafe in Millinocket, along with several other customers, all male and middle aged or older. The place opens daily at 5. Scrambled eggs, whole wheat toast, and home fries, hold the bacon.

Overheard snippets of wildlife conversation: "Fire up on the lake... clear the land... donít have to worry about the EPA... all them guys."

"An official member of the United States," someone on TV says.

The menís room here is just a few feet from the nearest table. Barely large enough to hold a toilet, it has no sink. Later it occurs to me that I might have asked if there was somewhere to wash my hands.

The big old red brick Millinocket High School building now houses apartments.

Time to hit the road, south and then west, toward the White Mountains. Why isnít New Hampshire called Blancmont?

By late morning, itís sunny and mild in the foothills and I stop at the public library in Rumford, Maine, where I sit at a computer and look out an open window at the Androscoggin River flowing past below. The library here subscribes to the magazine for which Iím the librarian. (That sentence makes me dizzy.)

Iíve gone from two nights of camping out, with no electricity, to checking my email, mostly so I wonít be so swamped with it upon my return home. Today I hear from friends in northern New York, southern Utah, Virginia, Oregon, and Illinois. Nowhere do I travel entirely alone.

At a rest stop north of the White Mountainís highest peak (Mount Washington), I stop and picnic on fig bars, nuts, and dried apricots, as a raven perches in a birch over my head. Below: a carpet of wild strawberries.

The White Mountains were named, Iím guessing, not because of snow but rather mist that enshrouds them, even on a clear day such as this. Some things--and creatures--are given names first, and later the names may seem apt or not. Other names come afterward, codifying what something has been called over time.

The mountains beckon me to stop, but I do not.

On the road: Six Gun City? An amusement park of sorts modeled after a town in the old West, oddly.

I make a detour to visit my paternal grandfatherís birth town, Littleton. Missing a turn, I find myself in Vermont before heading back and then following the Connecticut River south to Littleton which itself is set on the shallow Ammonoosuc.

And then I continue on to southern New Hampshire.

Late afternoon, Monadnock State Park. One of two rangers on duty here has just been chatting with a man he refers to as "Crazy Larry" who garnered that sobriquet for having hiked up Monadnock on 2850 consecutive days during the 1990s, a streak that ended on February 18, 2000. (Pneumonia. The better part of valor.)

Late afternoon, Monadnock State Park. One of two rangers on duty here has just been chatting with a man he refers to as "Crazy Larry" who garnered that sobriquet for having hiked up Monadnock on 2850 consecutive days during the 1990s, a streak that ended on February 18, 2000. (Pneumonia. The better part of valor.)

Black flies and mosquitoes swarm and bite my only exposed skin: Wrists and hands, including fingers and palms. No wonder birds live here and sing.

I hear the fluting of a thrush and a pileated woodpeckerís laughter.

Shreet? Right here. Reet eet? Yes, here! Red-eyed vireo.

I pitch a tent quickly, then go for a short walk. Displayed in a small park building, a scale model of the mountain shows at least seven trails to the peak, one marked with cairns, but all the others with paint.

Something there is that doesnít love a blaze.

Itís warm but I start a fire to discourage the darkness and insects. Itís come to this: Iím wearing a net over my head.

Suddenly a barred owl calls: WHO COOKS FOR YOU? Then a pair fly up and perch above me. Their call resonates like a cello: WHO COOKS FOR YOU-ALLLL. Thereís a scurrying at my feet. Terrified mouse?

The owls fly through thick woods skillfully and quietly.

Neither owl nor mouse, but made of the substance that connects them, Iím a lucky man.

Wodenís Day

Back home Iíd be sleeping or just awakening, but here and now Iím atop Monadnockís summit. A big rocky hill, really--only a leisurely two hour uphill hike and climb--but, at 3165 feet, itís considerably higher than Minnesotaís Eagle Mountain.

As Thoreau described it in 1852, "The summit is hardly more than a mile distant in a straight line, but about two miles as they go." Not that Thoreauís estimates of distance were often accurate without surveying tools.

So leisurely was my climb that though I was up at first light and didnít dawdle, two humans have passed me on the way, a young buck half my age (if that), and the ranger I talked with yesterday who stops to chat. ("Did you see the moose?" I didnít. The blasted netting blinded me.)

Turns out Crazy Larry "could only make it to the spring" yesterday. The eight and half years of daily climbing have wrecked his knees, perhaps. (Larry Davis is his name, and heís been written about not just in the local press, but in Outside magazine.)

A white throated sparrow sings. A jillion warblers and godknowswhat babble away, but I keep moving, bedeviled by flies. And sweating. The air is cool but fast warming.

"Itís still there," the ranger says, descending.

And now Iím up here alone on the rocky peak where water pockets of various sizes are not circular or oval, as is common in Utah, but sharply angular. A little grass grows in cracks, no shrubs or trees.

Everywhere rocks are carved with weather-worn graffiti, most from the 19th century. Thoreau was here, climbing Monadock four times between 1844 and 1860, and wrote in his journal during his third visit, in June 1858: "Apparently a part of the regular outfit of the mountain-climbers is a hammer and cold-chisel.... They are all of one trade, --stonecutters, defacers of mountain-tops."

Everywhere rocks are carved with weather-worn graffiti, most from the 19th century. Thoreau was here, climbing Monadock four times between 1844 and 1860, and wrote in his journal during his third visit, in June 1858: "Apparently a part of the regular outfit of the mountain-climbers is a hammer and cold-chisel.... They are all of one trade, --stonecutters, defacers of mountain-tops."

There has been much printed conjecture about what the name Monadnock means. Most commonly itís said to mean a single mountain standing up in an area without other peaks. The region here south and east of Keene is home to the Little Monadnock, Pack Monadnock, and Monadnock Mountains. Thoreau wondered about the provenance of these, writing from memory (in Concord, Mass.) in October 1857, "I fancy that they must have a corresponding under side and roots also. Might they not be dug up like a turnip? Perhaps they spring from seeds which some wind sowed. Canít the Patent Office import some of the seed of Himaleh with its next rutabagas?"

Mountains have also been compared to teeth, knives, and breasts, among other things.

Here the view is pastoral and calm compared to Ktaadnís wilder, sterner outlook. If my descriptions of what Iíve seen here are criticized chiefly because Iím an easy target, would that make me a landscapegoat?

On my way down the mountain I hear an ovenbird, chickadees, a mob of blue jays, a sweetly tootling thrush.

Blooming profusely in the woods: painted trillium (T. undulatum), a species Thoreau noted in his September 7, 1852 journal written while visiting here.

Mid-morning: I air my sleeping bag, pack my tent, then move out. Itís a sunny day. From the park entrance I turn north and before long Iím surprised to come to a town that is not Jaffrey (as expected) but apparently Dublin. Iím in Eire?

Thanks to the Dublin Public Library I consume a doughnut hole and orange juice, take a sponge bath in the rest room, check email (after turning on the computer), and learn a bit about the name Monadnock. Twelve variant spellings are listed in Grand Monadnock: Exploring the Most Popular Mountain in America, by Julia Older and Steve Sherman (Hancock, NH: Appledore Books, 1990). I donít transcribe the list, just run my eyes over the names. (I am not eidetic.)

Driving south I see an immature turkey vulture circle overhead.

What does it all mean? What to make of unexpected new vibrations and possibilities that present themselves? We are so finite, and yet...

By mid-afternoon Iíve gone from camping in the woods and getting eaten by insects to renting a room for a night in a plush Best Western motel in Concord, Mass. Compared to South Freeport, Maine, this place knows a different economy, but the deal comes with two passes to the Concord Museum, two lunches at a local restaurant, continental breakfast, cable TV (as if), coffeepot, Lorna Doones, an iron, a desk, and a balcony overlooking woods. Thereís even a coin laundry here, fitness center, and a pool. (Can I live here?)

I shower for the first time in four days, do some hand laundry (discovering the animal-nibbled holes in the shirt Iíd hung from the lean-to), drive back to downtown Concord, park, and walk to Walden Pond for the second time in eight months.

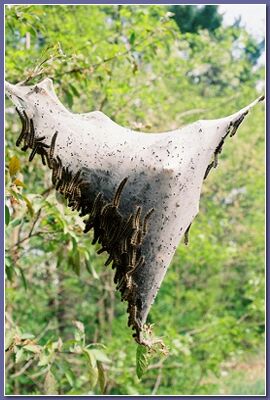

Tent caterpillars crawl into and out of holes in a white triangular silk purse suspended between two branches. Spring beauties bloom on Bristerís Hill.

Tent caterpillars crawl into and out of holes in a white triangular silk purse suspended between two branches. Spring beauties bloom on Bristerís Hill.

In Walden Woods I hear and see my first orioles of the season, along with blue jays, chickadees, tree swallows, catbirds, and a mallard, notice violets and yellow wild strawberries blossoming, and spot many chipmunks darting for cover.

The Shop at Walden Pond has three Thoreau volumes in Japanese, Civil Disobedience in German and Spanish, Walden in German. I talk for a while with the shop manager, then visit the replica house with its small table and cot, three chairs (for company), and stove. Windows on each side, about 4í x 6í.

The Fitchburg train (the T) rushes past, as do the cars of my day on the other side of the pond. (In Minnesota we would call this a lake. As deep as 90+ feet, Walden is far more vast than any so-called pond where I live.)

The beach is busy but not crowded, a few people swim, and diverse humans walk around or sit on the shore: Teenage boys talking about a friendís relationship with a girl ("Dude..."), a fisher, small children, people speaking languages other than English, teenage girls with hips and breasts that grow as they saunter. Along with the orioles, robins, mourning doves, and ants. (Not to mention fish.)

To get from Concord to Walden and back, one must cross a busy highway, Route 2. At least thereís a traffic light.

I go back to the motel and read for a while, a book I didnít know existed until about an hour ago: Walking With Thoreau: A Literary Guide to the Mountains of New England. The book culls Thoreauís writings about Wachusett, Greylock, Ktaadn, Kineo, Wantastiquet, Fall Mountain, the White Mountains, and Monadnock--from his journals, essays, and book The Maine Woods-- and organizes them geographically.

And then I sleep.

Thoreauís Day

From the motel balcony I hear and see flickers, starlings, catbirds, house sparrows, robins, a mourning dove, yellow warblers, and a goldfinch. One house sparrow and a starling disappear into a sort of apartment house: a dead tree full of holes drilled by a woodpecker.

I walk down the hall in search of food and find a roomful of it. The continental breakfast is distinctly above average, including hard-boiled eggs, fresh grapefruit, yogurt, croissants, and melon.

Why this infatuation with listing things?

I check out of the motel and drive the short mile and half to downtown Concord, then park and walk a few blocks--half a mile?--to the Concord Museum. On the way I pass the "First Parish in Concord" -- a Unitarian Universalist church founded in 1636.

At the museum entrance a woman examines the pass I hand her, the one I received at the motel, and makes a slightly sour face but says something like "thatís nice," hands me a visitor badge, and Iím in.

What is there about Concord we can disagree about?

Hereís a reproduction of Emersonís study, with some of its original furnishings, along with a source photograph and material about how historical rooms are recreated based on everything from details described in letters to bits of wallpaper found behind window frames.

And here are some of Thoreauís belongings: drafting tools and surveyorís chain, small desk, tiny chair that he turned into a rocker, a book of flute music (his fatherís) that he used to press flowers, a short walking stick he gave to his friend Harrison Blake (marked at one-inch intervals), and a birch tree tap he made for an experiment with making beverages from birch sap.

Here are snowshoes acquired in Maine the summer of 1853 (one with his name inscribed: H D Thoreau, Concord, Mass., the other with a price $5). Here is a blue box that contained pencils manufactured by the family, labeled thus:

Here is a wooden flute made of fruitwood, brass, and ivory, said to have been played by father and son, engraved--by whom and when?-- "John Thoreau +1835+ Henry D. Thoreau +1845+". And here, finally, is the smallest of objects displayed. In decrepit condition, itís nevertheless lovingly labeled by his sister Sophia: "The pen brother Henry last wrote with."

Thoreauís bed has been removed to an upstairs exhibit that opens in just over a week, a commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the publication of Walden. The bed is a rattan cot made in China, probably salvaged by Thoreau from somewhere in town (an early dumpster diver), to which he added legs.

The Thoreau family supposedly didnít consume coffee, tea, or sugar--saving up for a piano. (Did they ever acquire one?)

Among other items on display at the Concord Museum: a small hand-held fire screen (to protect the face while warming the body in front of a fireplace in winter), a hand muff, and a veritable foot muff, for stuffing oneís feet into while riding a horse-drawn sleigh.

A museum is a place to muse.

On this sunny morning I see my first chimney swifts of the season and hear them tittering as they dart in the sky.

I walk back downtown, then head west on Main Street past the library (closed for remodeling), to the intersection with Thoreau Street. Walking back from that intersection, the antepenultimate house on the south side of Main is marked with a small plaque identifying it as being the Thoreau house where Henry died, later purchased by the Alcotts. Is this 251 Main Street? Itís not marked, but just past 239 and 245, painted yellow, with a picket fence in front.

I walk back downtown, then head west on Main Street past the library (closed for remodeling), to the intersection with Thoreau Street. Walking back from that intersection, the antepenultimate house on the south side of Main is marked with a small plaque identifying it as being the Thoreau house where Henry died, later purchased by the Alcotts. Is this 251 Main Street? Itís not marked, but just past 239 and 245, painted yellow, with a picket fence in front.

Sometime midday I go to the cafe with my ticket for free lunch, and once again get a slightly grumpy reaction as I did at the museum. The hell with it. I order a special--goat cheese salad--and a cup of coffee. The java is good, and the salad excellent: dark greens, walnuts, so-called craisins (dried cranberries?), and goat cheese, with two wedges of pita. The restaurant fills up fast, and many of the customers are small children. I depart without asking for the dish of ice cream that was supposed to come with my meal.

After a quick stop at the West Concord library, I depart with mixed feelings, southbound to more people, some of whom are awaiting me, for a nieceís wedding and a reunion with my siblings. I will not write about these events, except to express admiration and tender feelings for my one-year-old grand-nephew Guy Edison Weibel who toddles eagerly into the world with arms lifted high to balance himself. (Geezer, as his Aunt Corey calls him.)

To write about or photograph some things is wrong. But there is no wrength to which some people wonít go.

How vulnerable can we allow ourselves to be? How honestly and openly can we speak? Can we communicate lovingly, do what needs doing, negotiate gently and honorably, give generously, laugh at ourselves, and accept a host of long silences, partiality, and emphatic noes? At times we humans lurch in the world with the gait and demeanor of Frankensteinís monster, terrifying kith and kin, no matter the purity of our hearts.

Not that our hearts are entirely pure. All of us are mixed. In Maine, Minnesota, or Montreal, we climb small mountains every day and gaze out with curiosity and affection. Then, having looked and pondered, gaining new perspective, we return to our roots.

You Are Here, northern Minnesota, November 2003

Porcupine Mountains, Michigan's Upper Peninsula, May 2003

Baptism River, northern Minnesota, March 2003

Cairn Free, southern Utah, November 2002

Red Cliff, south shore of Lake Superior, May 2002