Learning & Leading with

Technology, March 2001 v28 i6 p6

The Virtual Tour A Web-Based Teaching

Strategy. (how-to guide) Lawrence Tomei; Margaret

Balmert.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2001 International Society for

Technology in Education

Virtual tours introduce learners to an academic content

area by presenting a series of multisensory, multimedia

instructions for exploring material.

Perhaps for the first time since the computer made its

debut, the teacher is in the position to command the

technology-based instructional resources used in the classroom

Gone are the days when teachers must rely solely on the

expertise of computer professionals to create computer-assisted instruction. With the advent of the Web,

creating student-centered, age-appropriate material rests in

the hands of the classroom teacher. In their quest of

technology self-reliance, teachers can turn to the virtual

tour for the newest link to literally millions of

content-specific sites that supply images, sounds and video

media.

Defining the Virtual Tour

A virtual tour is a Web-based teaching tool that presents

multisensory, multimedia instruction appropriate for

individual student exploration as well as group learning

experiences. Virtual tours offer the learner a host of front

doors. A front door is a Web page constructed by the classroom

teacher that introduces academic content appearing on sites

throughout the Internet; it follows a specific format and

contains certain elements of lesson design that support

individual student learning. Each of the 14 teacher-developed

doors attempts to match an instructor's preferred teaching

strategy to a student's ideal learning style. Additionally,

the virtual tour offers the concept of amplified sites from

which to draw additional, up-to-date content. An amplified

site is a Web page or pages containing academic content and

linked on a front door; the teacher decides whether the site

contains the answer to one or multiple lesson objectives or

enough material to address the entire lesson. Plenty of

material on nearly every appropriate subject area can be found

on the Web. The tricks is using just the portion of a Web site

that addresses the particular lesson objective in the precise

format best suited to your students. Together, front doors and

amplified sites solve this problem.

From the Teacher's Perspective

Few strategies provide teachers with such rich

opportunities for expanding the walls of their classroom. The

virtual tour enhances curriculum with authentic learning

experiences in the form of exhibits, simulations, games,

portfolios, paths, galleries, guided tours, and linked

itineraries. Both cooperative and discovery lessons are

improved by focusing the virtual tour on instructional units

immersed in interpersonal communication, community awareness,

and technology objectives.

Preparing a Virtual Tour

Technology-based instruction is best prepared with the aid

of an instructional systems design (ISD) model, and the ADDIE

Model is an excellent choice for creating a virtual tour. By

following the five-step process, teachers Analyze, Design,

Develop, Implement, and Evaluate a technology-rich unit of

instruction employing all the strengths of the Web.

The ADDIE model is based on ISD concepts developed by

Robert Gagne, Leslie Briggs, Robert Morgan, and Robert

Branson. The ISD process provides the means for determining

the who, what, when, where, why, and how of instruction. The

concept of a systems approach is based on a generalized view

of teaching. It is characterized by an orderly process for

gathering and analyzing student performance requirements and

the ability to respond to identified learning needs. The

application of a systems approach ensures that the curriculum

and the required support materials (in our case, the

technology) are continually renewed in an effective and

efficient manner to match the variety of needs in a rapidly

changing environment. The ADDIE model's purpose is to:

* provide a systematic approach to designing lesson

content,

* identify the instructional goal and its context before

identifying a solution,

* provide a method of looking at instruction from the whole

rather than its parts,

* assist with better planning to make effective use of new

media and technology, and

* incorporate the latest teaching and learning theories

into the curriculum.

Additional information is available in Conditions of

Learning (Gagne, 1985) or by visiting Bob Hoffman and Donn

Ritchie's Web site at San Diego State University

(www.webcom.com/ journal/hoffman.html).

To aid reader understanding, we prepared a prototype

virtual tour to use as an example. The tour was based on an

actual lesson presented to sixth-grade students during the

1999-2000 school year on the topic of dinosaurs. Its design

followed the steps in the ADDLE model.

1. Analysis. The initial stage of any instructional

development effort determines the appropriate goals,

objectives, and content for the lesson. When preparing a

virtual tour, teachers must first select a topic best taught

using the Web-based format. Some topics lend themselves to

technology; others do not, and no quantity of images, sounds,

or video clips will make them successful. Once the content

focus is determined, the psychology for teaching the topic

(behavioral, cognitive, or humanistic) must be decided.

Behaviorally, the virtual tour is a natural extension of

sequential learning with content presented from first to last,

simple to complex, general to specific. The cognitive teacher

offers content in progressive steps until a schema, or

pattern, emerges to aid the learner in the construction of new

knowledge. Humanism offers a personalized approach to

learning, selecting information important to the student

although, for younger students, they may not be particularly

aware of what is or will be important to them.

The virtual tour makes the perfect integrated thematic unit

by combining several academic disciplines. As a result, the

analysis phase can be the most time-consuming step in lesson

preparation. In their backward design model, Wiggins and

McTighe (1998) suggest that learning goals must be the first

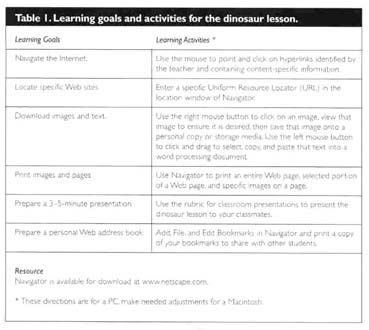

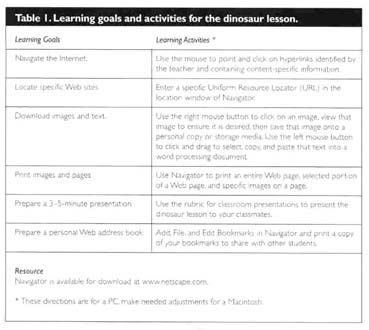

decision when creating the new lesson. Table 1 displays the

learning goals for the dinosaur lesson on the left and the

specific activity that is being targeted on the right.

Table 1. Learning goals and activities for the dinosaur

lesson.

Learning Goals Learning Activities(*)

Navigate the Internet. Use the mouse to point and click on

hyperlinks identified by the teacher and

containing content-specific information.

Locate specific Web Enter a specific Uniform Resource

sites. Locator (URL) in the location window of

Navigator.

Download images and Use the right mouse button to click on

text. an image, view that image to ensure it

is desired, then save that image onto a

personal copy or storage media. Use the

left mouse button to click and drag to

select, copy, and paste that text into a

word processing document.

Print images and pages Use Navigator to print an entire Web

page, selected portion of a Web page,

and specific images on a page.

Prepare a 3-5-minute Use the rubric for classroom

presentation. presentations to present the dinosaur

lesson to your classmates.

Prepare a personal Web Add, File, and Edit Bookmarks in

address book. Navigator and print a copy of your

bookmarks to share with other students.

Resource

Navigator

is available for download at www.netscape.com.

(*) These directions are for a PC; make needed adjustments

for a Macintosh.

2. Design. Lesson design begins by considering the target

learner. Piaget (1970) identifies a characteristic of learning

called "operations" and distinguishes between the concrete and

abstract learner, bringing to light the importance of making

instructional material age-appropriate for the learner.

Concrete learners (approximately 7 to 11 years old) demand

tangible experiences (e.g., images, sounds, and video clips)

supported by the virtual tour and the Web-based media on which

the tour is grounded. The abstract learner (ages 11 years and

older) revels in concepts and ideas (e.g., graphics and

hyperlinks) that support multisensory exploration.

Once the age and learning styles of the prospective

students have been established, specific learning objectives

can be formulated. For this task, many teachers prefer the

format attributed to Mager (1962). Its simplicity of design

makes the behavioral learning objective a natural for this

instructional format. Mager suggests three components for a

properly constructed objective:

* Condition provides the instruments for the learning

situation.

* Behavior is both observable and measurable. Activities

surround the lesson and present evidence that learning has

occurred.

* Criteria specifically details how well the behavior must

be performed to satisfactorily accomplish the lesson goals.

The behavioral learning objectives for the dinosaur virtual

tour are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Behavioral learning objectives for the dinosaur

lesson.

Objective I

Using a personal computer and Web address list, students

will navigate the Internet locating two specific dinosaur Web

sites and locate, download, and print at least two images of

their favorite dinosaurs.

Objective II

After locating a given Web site, students will review the

information and answer the questions in the workbook: "What is

the difference between an omnivore and a carnivore? When did

the dinosaurs live? What were the most common dinosaurs in

North America?"

Objective III

Given a Web address, students will click on a dinosaur name

to go to a simple black-and-white print-out and color, cut

out, and mount their favorite dinosaur for instructional use.

Students will be expected to provide a 3-5-minute presentation

on their chosen dinosaur.

![Full Size Picture]() 3. Development. With the analysis and

design firmly in mind, the next step is the advancement of the

lesson material. For the virtual tour, that means the

selection of a front door. There are actually 14 front doors

(Figure 1) that offer a facade for the tour and its many

amplified sites. Each is strong in a particular operation,

either concrete or abstract. Each is also tagged with a

psychology for learning: behavioral, cognitive, or humanistic.

And, because we are dealing with technology, each front door

has also been labeled easy, challenging, or difficult with

respect to the intricacy of the tools required to effectively

place the tour online. 3. Development. With the analysis and

design firmly in mind, the next step is the advancement of the

lesson material. For the virtual tour, that means the

selection of a front door. There are actually 14 front doors

(Figure 1) that offer a facade for the tour and its many

amplified sites. Each is strong in a particular operation,

either concrete or abstract. Each is also tagged with a

psychology for learning: behavioral, cognitive, or humanistic.

And, because we are dealing with technology, each front door

has also been labeled easy, challenging, or difficult with

respect to the intricacy of the tools required to effectively

place the tour online.

[Figure 1 ]

4. Implementation. Selecting a front door commensurate with

your lesson objectives and personal technical skills is not

difficult. With 14 available, the selection is based first and

foremost on your analysis of the lesson goals, followed by the

learning styles of the student, and then finally by the

technical expertise of the designer. For this article, we have

selected the six "easy" front doors to explore in detail: Next

Exhibit, Topical Path, Event Sequence, Chronology Text,

Gallery, and Itinerary.

![Full Size Picture]() Next Exhibit. One of the most readily

mastered formats for the virtual tour opens with an

introductory screen explaining the purpose of the lesson and

some simple directions. Textual material is held to a minimum;

images control movement throughout the lesson. The learner

travels sequentially forward to the next exhibit, returns to

the previous exhibit, or ends the tour at any point by

returning to the front door. The evaluation tag "ABE"

indicates that the Next Exhibit is Abstract, Behavioral, and

Easy. This means that it is most appropriate for teaching

abstract content to create a lasting image in the learner's

mind; it is behavioral in focus, presenting information from

first to last; and it is technically easy to create in both

concept and application. Figure 2 depicts the dinosaurs

virtual tour using the Next Exhibit format. Next Exhibit. One of the most readily

mastered formats for the virtual tour opens with an

introductory screen explaining the purpose of the lesson and

some simple directions. Textual material is held to a minimum;

images control movement throughout the lesson. The learner

travels sequentially forward to the next exhibit, returns to

the previous exhibit, or ends the tour at any point by

returning to the front door. The evaluation tag "ABE"

indicates that the Next Exhibit is Abstract, Behavioral, and

Easy. This means that it is most appropriate for teaching

abstract content to create a lasting image in the learner's

mind; it is behavioral in focus, presenting information from

first to last; and it is technically easy to create in both

concept and application. Figure 2 depicts the dinosaurs

virtual tour using the Next Exhibit format.

[Figure 2 ]

Topical Path (Figure 3). Also appropriate for abstract

content, this focuses on the delivery of content material

appropriate for discovery learning objectives. Learners are

provided an opportunity to use their prior knowledge (a

precept of the cognitive approach) by selecting

teacher-identified amplified sites containing additional

instructional materials.

[Figure 3 ]

Event Sequence. A lesson on dinosaurs might comprise many

mini-lessons; one for each of the scientific periods of

evolution. The Event Sequence front door focuses on a unique

era of evolving change or perhaps movement during a designated

time period. Highly abstract, this door is principally

humanistic in its presentation and relies primarily on

text-based links to its amplified sites. Figure 4 demonstrates

how the dinosaur lesson would look in the Event Sequence

format.

![Full Size Picture]() [Figure 4 ] [Figure 4 ]

Chronology Text (Figure 5). This front door uses the time

line approach to create text-based links to new information.

Each time increment is expressed in days, weeks, years,

decades, or centuries and is a link to more detailed material,

oftentimes created by the teacher. Remaining consistent with

the demands of the concrete learner, images augment the

instruction with multisensory features. Chronology is a

natural learning style for the behavioral lesson as it follows

the time increments to present the information. And, again,

dinosaurs are a likely topic for this front door format.

[Figure 5 ]

![Full Size Picture]() Gallery: One of the most popular front

door formats, the Gallery promotes cognitive learning using

images organized to follow the specific learning objectives of

the lesson. Amplified sites augment the instruction, and

sidebars (links provided on the left or right of the screen)

offer navigation beyond the lesson should students wish to

view additional materials. The Gallery's reliance on graphics

promotes concrete learning and fosters the building block

approach that cognitive learners relish. The dinosaur lesson

shown in Figure 6 uses the Gallery front door to present

material. Gallery: One of the most popular front

door formats, the Gallery promotes cognitive learning using

images organized to follow the specific learning objectives of

the lesson. Amplified sites augment the instruction, and

sidebars (links provided on the left or right of the screen)

offer navigation beyond the lesson should students wish to

view additional materials. The Gallery's reliance on graphics

promotes concrete learning and fosters the building block

approach that cognitive learners relish. The dinosaur lesson

shown in Figure 6 uses the Gallery front door to present

material.

[Figure 6 ]

![Full Size Picture]() Itinerary. The final easy front door is

patterned after a person's daily diary. It presents learning

as a series of related activities, appointments, and personal

memories. Most Itinerary virtual tours simulate the activities

of a subject during a "typical" 24-hour period, while others

chronicle events over a much longer period of time. Take the

dinosaur lesson, for example. Figure 7 tours the daily life of

a dinosaur from the perspective of "Rex." Itinerary. The final easy front door is

patterned after a person's daily diary. It presents learning

as a series of related activities, appointments, and personal

memories. Most Itinerary virtual tours simulate the activities

of a subject during a "typical" 24-hour period, while others

chronicle events over a much longer period of time. Take the

dinosaur lesson, for example. Figure 7 tours the daily life of

a dinosaur from the perspective of "Rex."

[Figure 7 ]

One of the many advantages of the virtual tour is the

flexibility that Web-based lessons offer the teacher. Though

other forms of educational technology demand considerable

computer storage resources, a tour is usually hosted on a

single floppy disk. Most of the resources of the virtual tour

are external sites. Only the front door itself, along with any

internal sites and related images, needs to be captured to a

local storage medium. Students can take the single floppy to

any Internet-ready computer in the school lab, classroom, or

even at home and immediately connect to the materials that the

teacher has prescreened for content and applicability. Or the

technology coordinator can upload the disk information to the

school's Web server for universal access and better teacher

control. Regardless, the virtual tour is becoming a popular

venue for the presentation of Web-based material. But until

now, no one has identified the various front door formats and

their pedagogical importance.

5. Evaluation. Educators often overlook the final stage of

the ADDIE Model, particularly when technology is used. Table 3

offers a final look at each of the six easy front doors

examined in this article and offers a few words regarding

their evaluative strengths and weaknesses.

Table 3. Evaluating the front door lesson.

Rating

Front Door (1-10) Comments

Next Exhibit 2 Assessment almost nonexistent;

requires external review using

objective tests such as

matching, true-false, or

completion.

Topical Path 2 Similar to the Next Exhibit,

this front door requires

external assessment using class

discussion or essay tests.

Event Sequence 4 Most effective evaluation for

this front door includes

authentic assessments such as

portfolios and thinking

journals.

Chronology Text 5 Use a hard-copy, text-based

quiz with this front door to

assess your students'

understanding of the material.

Gallery 6 With so many user choices for

this format, students are best

assessed using typical

discovery learning techniques

such as group work reports,

and presentations.

Itinerary 5 Subjective evaluations are most

appropriate here. Assess your

students' knowledge with

reports.

![Full Size Picture]()

![Full Size Picture]() Conclusion Conclusion

Keep in mind that there are eight additional front doors

available for presenting abstract and concrete ideas;

behavioral, coghitive, and humanistic content; and technically

challenging or difficult construction. If you would like to

visit representative sites of these remaining formats, see

Table 4 for URLs of some good sites discovered so far.

Table 4. The remaining front doors and representative

Internet sites.

Front Evaluation

Door Tag Site Name URL

Guided ABC U.S. www.whitehouse.gov/

Tour White House WH/glimpse/tour/html/

index.html

Table ACC Dragonfly http://tess.uis.edu/

Museum www/environmentaled/

Map/ ACD Gordon's www.pgordon.com/

Globe Ongoing

Journey

Room AHD Museum of www.imss.fi.it/

Exhibit the History museo/4/

of Science

Timeline CBD Olympic http://

Map Games: devlab.dartmouth.edu/

Victors olympic/Victors/

Picture CCC Wonders of http://ce.eng.usf.

Button the Ancient edu/pharos/wonders/

World

Button CCD Oswego City http://oswego.org/

Advance School District staff/cchamber/web/

default.htm

Vehicle CHD The U-505 www.msichicago.org/

Submarine Tour exhibit/U505/

U505tour.html

![Click for Full Size]() Using the virtual tour format and these front

doors, teachers can design their own online resources for the

classroom. They no longer must rely on the computer

professional to create technology-based instruction. The

virtual tour is the answer to locating, organizing, and

incorporating millions of content-specific sites into

student-oriented online lessons. Using the virtual tour format and these front

doors, teachers can design their own online resources for the

classroom. They no longer must rely on the computer

professional to create technology-based instruction. The

virtual tour is the answer to locating, organizing, and

incorporating millions of content-specific sites into

student-oriented online lessons.

References

Gagne, R. M. (1985). Conditions of learning and theory of

instruction (4th ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Mager, R. F. (1962). Preparing instructional objectives.

Palo Alto, CA: Fearon Publishers.

Piaget, J. (1970). Science of education and the psychology

of the child. New York: Viking Press.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by

design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development.

![Click for Full Size]() Dr. Lawrence A. Tomei (tomei@duq.edu)

is an assistant professor of teaching and technology. His

responsibilities include developing and teaching workshops,

seminars, and in-service programs for practicing teachers. His

expertise includes educational psychology, teaching and

learning strategies, and technology use in the classroom. He

earned his EdD from the University of Southern California.

Reach Dr. Tomei at Duquesne University, 209C Canevin Hall,

Pittsburgh, PA 15282; 412.396.4039; fax 412.396.5388. Dr. Lawrence A. Tomei (tomei@duq.edu)

is an assistant professor of teaching and technology. His

responsibilities include developing and teaching workshops,

seminars, and in-service programs for practicing teachers. His

expertise includes educational psychology, teaching and

learning strategies, and technology use in the classroom. He

earned his EdD from the University of Southern California.

Reach Dr. Tomei at Duquesne University, 209C Canevin Hall,

Pittsburgh, PA 15282; 412.396.4039; fax 412.396.5388.

Maggie Balmert (balmert@ duq.edu) is a full-time academic

advisor for Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Maggie is currently completing a master's degree in

instructional technology there. She holds a Bachelor of

Science degree from Indiana University of Pennsylvania and is

a former high school teacher for the Greensburg Salem School

District in Greensburg, Pennsylvania. Reach Maggie at A. J.

Palumbo School of Business Administration, Duquesne

University, 600 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15282;

412.396.5702; fax 412.396.5304. |