Bruce Amspacher - April 11, 2003

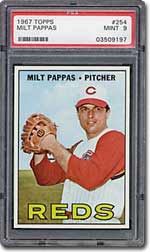

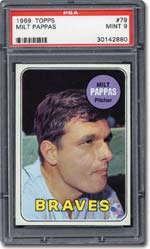

Milt Pappas was a major league pitching star for 17 years, posting 209 wins and a lifetime ERA of 3.40 while hurling for the Orioles, Reds, Braves and Cubs. He pitched in two of the most famous regular-season games in the history of baseball; one being the infamous "asterisk" game in 1961 and the other being the controversial near-perfect no-hitter that he twirled in 1972. There is a great deal of rumor and legend surrounding those two games, and it is sometimes difficult to discern the absolute truth -- the "what really happened" -- from the many different stories that swirl around those historic 18 innings of decades ago. In order to set the record straight, I conducted an exclusive interview with Milt Pappas just as the 2003 baseball season was getting underway. BA: Take us back to September 20th of 1961 and tell us what happened. Did you really tell Roger Maris what you were going to throw him? If so, why? Pappas: It was the 154th game of the year. In Babe Ruth's day the complete schedule was 154 games. By 1961 the schedule had been expanded to 162 games. The commissioner of baseball said that Roger Maris had to break the Babe's one-season home run record in 154 games or there would be an asterisk by his name and record. It was a stupid ruling. Maris was a great guy, a fine offensive player and a tremendous defensive outfielder, but the press hated him. They hated him for two reasons. One, he gave one-word answers to their questions. Second, they had the attitude of "How can you do this to the Babe by breaking his great home run mark?" Maris was just a farm boy from the Dakotas and here he was under all this pressure and receiving all this hate mail. He was going through hell. The night before the 154th game I saw Maris and Mickey Mantle walking under the stadium. We stopped to talk and I told Maris that I wanted to see him break the record. I told him that I was going to give him nothing but fastballs tomorrow. Maris said, "Really?!" I told him, "Absolutely." Mantle was listening to all of this with wide eyes. Finally he said, "What about me?" "You're on your own, big boy," I said. So, the next night the game was nationally televised, which was a big deal in 1961. Maris was sitting on 58 homers for the year, so he needed two to tie and three to break the record. The first time up he tagged it, but it stayed in the park. The second time up he hit it out and now had 59 for the year. I didn't get to finish the game or he might have tied or broken the record that night. BA: Did you ever tell any other players in any other games what pitch was coming? Pappas: One time. I was scheduled against Pedro Ramos of the Twins. I said, "Hey, Pedro, tomorrow let's throw each other nothing but fastballs." Pedro loved the idea. The first time up I gave him a fastball and he hit it right on the button. My center fielder made a great play to track it down. Pedro gave me the promised fastball and I hit it out. The next time Pedro hit another line drive, but once again my defense saved me. Pedro only threw me one more fastball, then he switched to curve balls. Unfortunately for him, he hung the second curve and I hit it out of the park again. I'm glad I don't speak Spanish because he was really giving it to me as I rounded the bases. We won the game, 3-0. BA: Before we get to the no-hitter, tell me about getting to the major leagues and your first memorable experience. Pappas: I was signed directly out of high school. I only pitched three games in the minor leagues, then I was called up to the Orioles. I was pitching in the major leagues at the age of 18, facing the man who was the most mind-boggling hitter who ever lived -- Ted Williams. I get a 3-2 count on Williams and I throw him a pitch that cuts the heart out of the plate. He just stands there and the umpire doesn't say anything for about 15 seconds, Finally, Williams turns and goes back to the dugout and the umpire yells, "Strike three!" I walked up to the ump after the inning was over and asked him, "What would you have done if Williams had trotted down to first instead of going back to the dugout?" "Then it would've been ball four," the umpire replied. "His eyes are a whole lot better than mine are." BA: On September 2, 1964 you nearly pitched a no-hitter, taking it into the eighth inning against Minnesota. Eight years later to the day, September 2, 1972 you pitched one of the greatest games in history. What happened in the ninth inning? Pappas: I was pitching for the Cubs at Wrigley Field against the San Diego Padres. I retired the first 26 batters in the game and I needed one more for a perfect game. There had only been seven perfect games [in the 20th century] up to that time. Larry Stahl was sent up to pinch-hit and I got two strikes on him immediately. Randy Hundley [the Cubs' catcher] called for a slider. Ball one. Slider. Ball two. Slider. Ball three. Slider. Ball four. Stahl walks and the perfect game is gone. BA: Were any of the last four pitches strikes? Pappas: Any one of the four could've been called a strike and the last two were definitely strikes. [Umpire Bruce] Froemming came out to the mound after Stahl walked and I called him every name that I knew in the English language. When I ran out of names in English I started calling him names in Greek. BA: Weren't you afraid of getting kicked out of the game? Pappas: There's no way in hell that he was going to kick me out of the game. Not that game. Not if he wanted to get out of Wrigley Field alive. Everybody was too mad at him. The players, the fans -- everyone. So I went back to pitching and got the final out on a pop-up to second base to preserve the no-hitter. BA: Then what happened? Pappas: Believe it or not, the next day Froemming comes over to me and asks me to autograph a baseball for him. So I autographed it for him and then made a suggestion as where he might want to put it. He was incredulous. "You're not still angry at me, are you?" he asked. "You have no idea what you did," I told him. "You blew it! You had a chance to call one of the few perfect games in the history of baseball and you blew it." "Show me an umpire who ever called a game without making a mistake," he answered. I couldn't believe he said that! He missed the point. Then I ran into Larry Stahl. Stahl said that he wanted me to get the perfect game so after he got two strikes on him he decided not to swing anymore. "Why didn't you say something?! Why didn't you back out of the box and give me a wink or something?!" I asked him. I would've been happy to give him a fastball down the middle if I knew that he wasn't going to swing at it. BA: Why do I feel that there's even more to this story? Pappas: There is more to the story. I have the ninth inning of that game on tape. It's the only part that WGN recorded for some reason. I had some friends over the other night and they wanted to see the ninth inning. So I played it and I watched Froemming after I had my cussing match with him at the mound after Stahl walked. As he was walking back to the plate he had this big snicker on his face. His face said, "Ha, ha, got ya!" BA: These are some of the best baseball stories I've ever heard. Can we make this a ten-hour interview so that I can hear them all? Pappas: I've got most of them written down. I published a book a couple of years ago entitled "Out at Home" that tells the story of my baseball career. If your readers would like one, I'll mail them an autographed copy for $30. BA: Thank you very much! Pappas: My pleasure. **** Milt Pappas's rookie card is #457 from the 1958 Topps set. It carries an SMR value of $150 in Mint-9. "The paper was not very good on the '58 Topps, but the last series is a little better," says Clay Hill, a renowned sportscard expert from Sportscards Plus in Laguna Niguel, California. "The cards are really hard to get nice. Print defects are a real problem, but at least the last series has good sharp corners, unlike the earlier issues of 1958." Are there any other cards of Milt Pappas that are of special interest? "His 1967 Topps card is a real mystery," Hill said. "It is the only one in the entire series that doesn't have a facsimile autograph. I'd really like to know why." Good. That will give me an excuse to call him back to hear more baseball stories!

|

|||

![]() Click

here to email this article to a friend.

Click

here to email this article to a friend.

PSA Library