Prior to my recent trip to Ireland, I had never really thought too much about going there until a year or so ago when I had seen a Public Television special on the Irish Potato Famine; this seized my mind. I began to contemplate the devastation of those years and what my ancestors had gone thru and I began to think of visiting the rural areas of Ireland where this had taken place.

To me a journey is as much the emotions and thoughts that lead toward the trip as is the actual physical trip itself. How does the imagined place we build in our mind before hand jibe with the reality of the place? What is the reality of a place? How are our experiences as visitors different than those of the inhabitants? Putting aside the clichéd images, what is the essence of a place?

I have always questioned the ethics of being a tourist. Tourists change the place they visit. Whether it is the Gettysburg Battlefield, the Wisconsin Dells, Yosemite Valley or the villages of Nepal, tourists alter the landscape and the societies that exist on that landscape. Motels pop up, large tour buses lumber through narrow spaces, souvenir shops and McDonalds proliferate and the essence of the place is generally radically altered and often destroyed. Casual visitors often "love a place to death".

When going in the wilderness, I've grown up with the ethic of "leave no trace" camping in which one doesn't start a camp fire, packs out all waste, and alters the landscape as little as possible. "Step lightly" is the motto.

So, first I had to consider whether in going to Ireland was I just going to be another "Tourist" and whether this was good for Ireland. I thought about this quite a bit and decided that if I stay out of the cities, and went during the "off" season when life was quiet, I would not contribute too much to the din of the "Tourist" season.

From my research I saw that many rural Irish families supplemented farm income by taking in travelers into their homes as Bed and Breakfasts (B & B's). Also, Ireland is one of the few countries in Western Europe that has less population than it did 150 years ago. In the 1840 census, Ireland had a population of over 8 million. Today, that number is closer to 4.5 million. For much of the 19th and almost all of the 20th Century, because of poor economic prospects at home, Ireland has hemorrhaged people, who have emigrated to England, the Americas and Australia. So, I again rationalized that there was room in Ireland for one more light-stepping traveler.

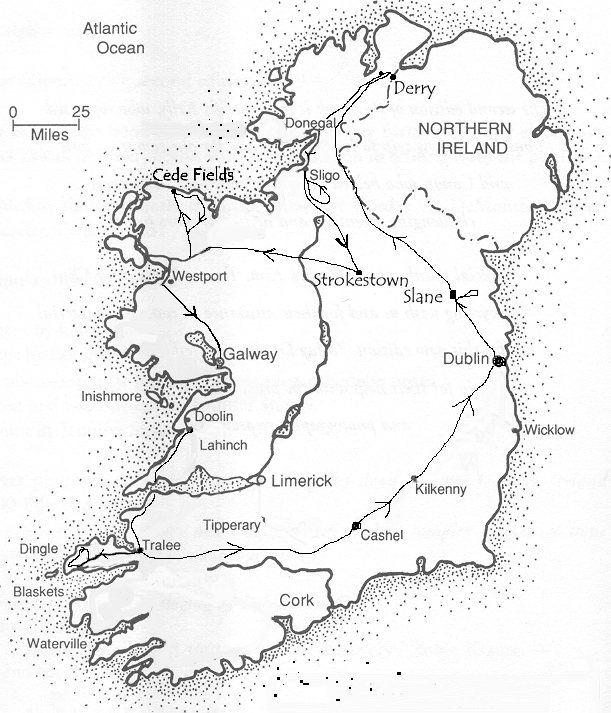

Having become clear of this in my own mind, I considered what my aims were for the trip. I didn't come up with any specific goals but rather looked at this as an exploration (reconnaissance) of the countryside as well as a kind of personal pilgrimage. I laid out as a general principle that I wanted to avoid the big cities of Dublin, Limerick and Cork. I conceived that I would circle the Island in a counter clockwise direction, and came up with a dozen or so sites to visit, like so many "stations of the cross".

In terms of the actual trip itself, I made arrangements to arrive in mid-March when the weather was still cool, around 40-50 degrees Fahrenheit. The weather was likely to be gray and rainy quite a bit of the time; I packed good rain gear. I arranged to have vouchers for B & B's each evening although I could only make reservations for the first night after my arrival. The rest of the time I would have to call ahead to make arrangements for the coming night. I also had arranged to rent a car with unlimited mileage for the week. I knew that on landing in Dublin I would have to immediately learn how to drive on the left side of the road which caused me some anxiety.

I won't go into the details of the flights other than to note that I took IcelandicAir directly from Minneapolis to London, making connections in Reykjavik. From London I took a British Midlands Airlines flight to Dublin. This went about as I had anticipated.

On landing in Dublin on a late Saturday afternoon, I exchanged my American currency for Irish and then took a shuttle out to the parking lot where I picked up the car, a little Opel Station Wagon. After venturing into traffic and dealing with the novelty of driving on the left side (steering wheel on the right) I managed to get lost on the highways that ring Dublin. After stopping to ask directions a couple times, I managed to find the highway I wanted which took me north, out of the city, toward the B & B at Slane, where I was scheduled to stay the first night.

At this

point I'd mention that each evening, during the trip, I would spend an

hour or two in my room, keeping a travel journal in which I would write

down what I had seen, who I had met, and my impressions and reactions to

the day's experience. By the end of the trip I had close to 40 pages

of handwritten notes. As I mentioned before, I look at a journey

as starting long before the actual travel begins. Similarly, I consider

the journey to continue long after the actual trip is over and the bags

are unpacked and the clothes laundered. The journal is for me a tool

for reviewing, and considering what I experienced during my travels.

At the time of this writing I have been back in the United States slightly

less than a week. I continue to make notes in the journal as I come

up with further thought about Ireland and the people I met and the places

I saw.

At this

point I'd mention that each evening, during the trip, I would spend an

hour or two in my room, keeping a travel journal in which I would write

down what I had seen, who I had met, and my impressions and reactions to

the day's experience. By the end of the trip I had close to 40 pages

of handwritten notes. As I mentioned before, I look at a journey

as starting long before the actual travel begins. Similarly, I consider

the journey to continue long after the actual trip is over and the bags

are unpacked and the clothes laundered. The journal is for me a tool

for reviewing, and considering what I experienced during my travels.

At the time of this writing I have been back in the United States slightly

less than a week. I continue to make notes in the journal as I come

up with further thought about Ireland and the people I met and the places

I saw.

From Slane in County Meath, I visited Newgrange to the East. Newgrange is a 5000+ year old mound built by pre-Celtic people. It is a passage tomb although apparently no bodies were ever kept in it for any length of time. There is a long passage into the mound and visitors are allowed to snake there way down into the core of the mound where an archeologist gives a lecture on the origins of the tomb. The passage is aligned so that the rising sun's light reaches the back of the tomb on the spring equinox. Newgrange sits in hilly dairyfarm country, looking down at the Boyne River.

After visiting

Newgrange, I spent the day driving north and ended up in County Donegal.

That evening I had a long conversation with a farmer, Mervyn, who

owned the B & B where I stayed. He was a sweet man; we

talked for two hours. Although Donegal is part of the province of Ulster,

it is not part of Northern Ireland but rather part of the Republic of Ireland.

After visiting

Newgrange, I spent the day driving north and ended up in County Donegal.

That evening I had a long conversation with a farmer, Mervyn, who

owned the B & B where I stayed. He was a sweet man; we

talked for two hours. Although Donegal is part of the province of Ulster,

it is not part of Northern Ireland but rather part of the Republic of Ireland.

The next day I set out looking for the ring fort, Grianan, west of the town of Derry. In the process of looking for the fort, I drifted too far east and before I knew it, I was in Derry and so in Northern Ireland! Derry is an old walled city. In the town I saw murals of William of Orange on his horse. I also drove by graffiti for the provisional IRA. So, I knew I was in unsettled territory and as quickly as possible, I headed west and back into the republic.

After further searching I found Grianan. It was on a hill, looking down it all directions. It was obvious that this was a strong hold for many generations of Celtic warriors, long before St.Patrick came and converted Ireland to Christianity. Outside the perimeter of the fort, in fact, was a spring that is a shrine, commemorating where St. Patrick baptized a Celtic Chief who was master of the region and who used the fort as his strong hold.

After leaving Grianan, I wandered southeast and that evening ended up at a rural B & B on the coast, west of Sligo. That evening I walked along the deserted coast, listening to the sea birds and ducks. I walked up a narrow lane by a number of abandoned cottages. Along the way I met two farmers who were trying to move some cattle down the road and helped them turn the beasts into a corral gate.

That evening I watched Irish Television in my room. The public station had a special on Ireland in the 1950's and how the economy was so poor. Tuberculosis was a scourge well into the 1950's and many people went to the sanitarium to recover or linger or die. Words like despondency and protectionism came up. In just one year, 1955, over 55,000 people emigrated from Ireland. "We were Irish, Someplace Else" was a phrase that stuck in my mind. While western Europe was booming in the 50's, Ireland did not.

The next day, Tuesday, I drove back east and south of Sligo and visited the ruins of Crevelea Abbey that had been built by Owen O'Rourke in the 1500's. Then I drove down the road and visited Parke's Castle.

The O'Rourkes were chiefs of the Breffni area for many hundreds of years and two O'Rourkes were kings of Connaught, one of the four provinces of Ireland. The O'Rourkes and the O'Reillys were kindred ruling families and built a string of castles on the borders of their dominions. But they were continually at war with the English. Their worst offense was that in 1588, Brian O'Rourke sheltered Captain de Cuellar, the shipwrecked Spanish Armada. For this offense along with making general war on the English, Brian was eventually captured and hung on the gallows at the Tower of London. His lands were confiscated and redistributed to English settlers. The O'Rourke Castle, their stronghold on Lough Gill was destroyed and a new residence stronghold, was built by Robert Parke. This is what remains to this day. Those O'Rourke clan leaders who were not killed by the English, fled the island, part of the migration of "The Wild Geese". A number of O'Rourkes ended up working as mercenaries in the armies of Europe, going as far east as Poland and Russia.

After walking around the castle of the Englishman, Parke, I headed South East to Strokestown to visit the Famine Museum there. I was the only visitor there that afternoon and spent a couple hours slowly walking thru, reading every word of each exhibit and looking at the records and letters and artifacts from this holocaust.

The

Famine was the great catalyst which ultimately caused

everything to change in Ireland. Without the famine, Ireland might

have ultimately ended up remaining part of and becoming assimilated into

the British nation, like Scotland or Wales. But the Famine drove

so many Irish out to America, where they ultimately prospered and were

able to send back financial support to those brothers and sisters who remained.

This support ultimately provided a major part of the finances for the revolution

of Republicanism in 1916 and the subsequent Anglo-Irish War.

Even after separation from Britain, the Irish have never forgiven the English

for the famine.

The

Famine was the great catalyst which ultimately caused

everything to change in Ireland. Without the famine, Ireland might

have ultimately ended up remaining part of and becoming assimilated into

the British nation, like Scotland or Wales. But the Famine drove

so many Irish out to America, where they ultimately prospered and were

able to send back financial support to those brothers and sisters who remained.

This support ultimately provided a major part of the finances for the revolution

of Republicanism in 1916 and the subsequent Anglo-Irish War.

Even after separation from Britain, the Irish have never forgiven the English

for the famine.

After visiting the museum, I drove west to Westport where I stayed for the night. Westport was the port where, in the late 1840's, many of the Famine Irish went to get on ships to take them North America. These were later referred to as "Coffin Ships" since thousands died on these voyages or after they landed in the new world. I remember reading a journal entry by Henry David Thoreau of when he was walking along the seashore in New England and a ship had wrecked off shore during a storm and the bodies of the Irish emigrants, having fled death in Ireland, had drowned just as they were within sight of shore. The bodies and men, women, children and babies were washed up on the shores, to Henry's horror.

I visited the old stone quays where many of these ships had departed, bound for Quebec, New York and Boston. This was a place to pause and ponder the humanity which passed thru this place. After visiting the quays, I spent some time in the downtown that evening and the next morning. I chatted with several people and visited bookshops, outdoor equipment stores and stuck my head in a couple pubs.

Before taking the trip I had planned to take a hike up Crough Patric, a 2500 foot hill to the southwest of Westport. This is a holy site where many pilgrims climb up, often barefoot, in homage to St. Patrick. When I was there the clouds hung low over the mount and I thought better of hiking in a damp, thick fog.

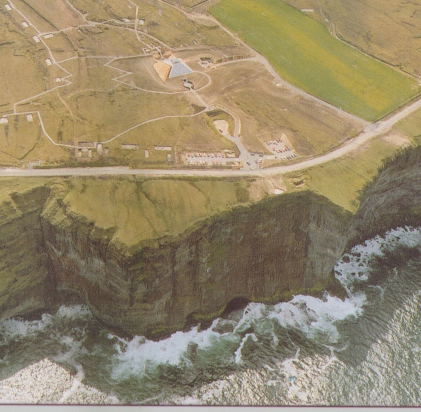

Wednesday

Morning I drive north until I reach the north coast of County Mayo

to visit Cede Fields (pronounced Kaja'). The setting is a

bog that overlooks 500' cliffs; the North Atlantic Ocean pounds on these.

Cede Fields is an archeological site that was established when local people,

digging peat out of the bogs began finding stone fences 15-18 feet below

the original surface of the bog. Archeologists came in and by probing

and strategic diggings found an extensive series of rectangular fields

bordered by stone fences. These fields are over 5000 years old and

were evidence of a farming community in which peoples came in and cleared

out extensive forests and began farming the land. Only later, as

the moisture built up did the bogs begin to build up and eventually cover

over the fields in this particular spot. There is a large interpretive

center (in the shape of a pyramid) near the cliffs and I spent a couple

hours walking through the exhibits and then out in the fields themselves.

Ireland was settled much earlier than people originally thought!

Wednesday

Morning I drive north until I reach the north coast of County Mayo

to visit Cede Fields (pronounced Kaja'). The setting is a

bog that overlooks 500' cliffs; the North Atlantic Ocean pounds on these.

Cede Fields is an archeological site that was established when local people,

digging peat out of the bogs began finding stone fences 15-18 feet below

the original surface of the bog. Archeologists came in and by probing

and strategic diggings found an extensive series of rectangular fields

bordered by stone fences. These fields are over 5000 years old and

were evidence of a farming community in which peoples came in and cleared

out extensive forests and began farming the land. Only later, as

the moisture built up did the bogs begin to build up and eventually cover

over the fields in this particular spot. There is a large interpretive

center (in the shape of a pyramid) near the cliffs and I spent a couple

hours walking through the exhibits and then out in the fields themselves.

Ireland was settled much earlier than people originally thought!

Cede Fields, Newgrange and a number of other historical sites are administered by Duchas, the Heritage Service of Ireland. They also maintain the country's national parks. Duchas supports archeological digs and scholarly research into Ireland's heritage. My impression is that it is a bit like a combination of the U.S. National Park Service and the Smithsonian Institution. Duchas has a a homepage where the observer can find a listing of the sites it maintains, as well as many scholarly papers which one can download.

After leaving Cede, I headed down south again. After making a brief stop in Westport I continued down to Galway Town. I made a conscious decision to skip the Connemara region of County Galway. This is a special region that the Irish government has designated as a park. Connemara was one of the most isolated areas of Ireland in previous centuries and Gaelic was still spoken here by a significant portion of the population into the early 20th century. There are several large ranges of hills that run through the region and it was a coast made up of a number of smaller bays and inlets. I had originally planned to visit but decided that I would reserve Connemara for a future trip when I could experience it in more depth.

When I arrived in Galway Town, I breezed right thru to the east since I still wanted to avoid cities. Once east of town I found a B & B run by a dairy farm family and there I stopped. It was late afternoon. After paying and getting a key for my room, I headed out and drove a mile and a half further east to the little town of Oranmore. There, I parked the car and strolled thru town and did a little grocery shopping. Then I headed out to the shore of Galway Bay and sat down on some rocks and took out of my pack a loaf of bread, sliced ham and mustard and made a couple sandwiches. As the sun dropped lower in the sky, I contemplated a well-maintained Norman keep. I strolled up towards the keep and realized that it was being used as a residence. Later that evening I learned that Winston Churchill had owned it and that after he had died it had passed on to his daughter. Now, her niece apparently lived there. Interesting. After eating my sandwiches, I packed up my bag and went for a stroll.

I came upon an old cemetery surrounded by a high wall. Unlike other cemeteries I had visited on my trip, this one was full of rubbish and a number of head stones had been vandalized and toppled. The trashiness of the spot surprised me and later I asked the family of the B & B about it. At first no one could remember this old cemetery and then one person recalled it. It was an abandoned Protestant cemetery. The families who's people had been buried there had all left the region going to Northern Ireland or back to England and there was no church left to maintain it. I saw this as an unspoken witness to the old hurts of the past and the unforgiving nature of human history. The trash seemed to say, "To Hell With Them!"

Thursday morning I drove south and west, following the south shore of Galway Bay. At a gas station a lady hears my American accent and asks where I'm from. The midwest. Oh yes, she says. I lived in Boston for 30 years. Welcome home!, I exclaim.

At the town of Kinvarra I stop and admire another well-maintained Norman Keep, almost a castle with a strong wall surrounding it. At a grocery store I ask the directions to Kilmacdough. A famous set of ruined abbey and cathedral along with a round tower. A woman at the store takes me out on the street to give me directions. She is kind and warm and she mentions that her parents are both buried there. "A very holy place", I say. She smiles back and nods at my understanding. "Yes, a very hold place" she repeats.

I am struck by the religious feeling of rural Ireland. The Catholic churches look well maintained and attended. The cemeteries (Catholic) are well maintained and fresh flowers are often in attendance. During my trip, the Pope John Paul was visiting the middle east and there was much coverage of his pilgrimage, both on the radio and on the television news. At B and B's I almost always see paintings of Mary and Jesus and often I see catechisms in the bookshelves.

The Catholic Church is still a dominant presence in rural Ireland. Obviously, not all Irish love the church. The singer, Sinead O'Connor, tore up a picture of the pope a couple years ago, causing great controversy. Frank McCourt's popular book, Angela's Ashes was not, I am told, complimentary of the church. Still, Mother Church is always present. Shines, both large and small, are everywhere. The history of Ireland, the suppression of the Catholics by the English, and the ultimate dual identity of "Irish Catholicism" endures both in the people and the rural landscape.

The grocery woman's directions were perfect and I found the shrine of Kilmacdough far out in the countryside. I walked over the site for half an hour. As in many of my travels, I had the whole place to myself. The round tower loomed over the site. In the old cathedral and surrounding it were the graves of the local people. Outside the cemetery area there was one old church which was over 1300 years old. Sheep grazed around it. A soft mist of rain fell and I listened to the silence.

Back in the car, I headed down the narrow country road. I turned on the radio and listened to an interview of an American born author who had just written a book on the famed Mountjoy Prison. Over 50 people were hung there, a number of them political prisoners. It was developed in the 19th century as a progressive model prison, based on Quaker principles of the "Penitentiary" where silence was maintained and each prisoner was isolated in his own cell 23 hours a day to contemplate his wrongs and repent. While this was an improvement over previous prisons, the solitude for the prisoners became sheer torture for many.

My next stop was Ennistymon, a town a little east of the Atlantic Coast. I had specifically come to visit another rural cemetery. This cemetery was on a steep slope out in the country. There were sheep droppings in it and bares spots which were muddy in the mists. There were no headstones except for one at the base of the hill. I walked up the hill, looking at the long broad depressions in the ground which collected sitting water. This was the old Ennistymon Workhouse Cemetery. The workhouse was a half mile to the north east but has been gone for many years. The broad depressions are old trench graves where the bodies of the starving Irish were interred without coffins. The bodies were stacked up to five deep and the trenches were long enough to accommodate hundreds of dead who filled up the graves over a short period of time. The trenches were covered and new trenches were dug and new dead filled them.

Over the last 150 years, the trench graves collapsed in as the bodies decayed away and now the only sign of the dead is the gaping volume of these pits. As I think of Newgrange and Kilmacdough and the old Protestant cemetery, I think about the messages some grave yards can tell. There is only one headstone near the bottom of the hill. I make out an inscription, "Mary Ceracht (?) ..this...in memory of her beloved husband, John, died 1916, age 86". I do the math. He would have been a young man during the famine. Rather than be buried in a regular cemetery, he is buried here, amongst the paupers. Were one or both of his parents or siblings buried here? A sweetheart? In death, was his wife returning him to the unmarked graves of his loved ones? Again, I stood and contemplated. Sheep bleated in the distance. The mist continued. I stepped carefully out of the muddy field and climbed over the fence and walked back to my car.

On leaving the cliffs, I drove south for an hour and took a ferry over the broad estuary of the Shannon River. This brought me into County Kerry. My goal was to visit the Dingle Peninsula.

I passed thru the city of Tralee and headed east, down the northern coast of the Peninsula and then passed over Connor's Pass. Normally, the pass is supposed to be a wonderful prospect from which to look over much of the area. However, the mists had turned into a heavy shower. It is dusk and I saw two forlorn hitchhikers along the road standing in the increasing rain and I stopped and gave them a lift to Dingle Town. They were both young, one was 18. The other was 21 and an apprentice stone mason. They were sweet boys and were heading off to Dingle to visit the pubs. We had a good chat has we wound up and over the pass. A fine night to travel on foot!

That night I stayed at another dairy farm B & B. On Friday morning I got up early and took an walk. It was a sunny, clear morning. I listened to the sound of a vacuum pump (for milking cows) buzzing in the distance and the sound a dog barking, apparently helping move cows into a milking parlor. Ireland is now part of the European Union and will be losing full time farmers over the next ten years as price supports and subsidies are gradually withdrawn and farms have to depend completely on the free market. Fortunately, the Irish economy is booming. Many high tech firms, both from the United States and Europe have located in Ireland. There is a building boom in Ireland at present and new houses are being built all over the country. Many farmers will probably continue to farm on a part time basis. This seems to parallel the trend of dairy farmer friends back home in Western Wisconsin.

The dairy family where I am staying used to keep people in two spare bedrooms in their stone walled farm house. Within the last year they built a new B & B facility with 6 bedrooms separate from the house. They also have added an outside tennis court. Obviously, they have made a calculation to refocus on the tourist trade and depend less on the farm's income.

After having the typical "Irish Breakfast", eggs, sausage and ham, along with plenty of toast, I head out to "Slea Head" at the farthest reaches of the peninsula. This is dramatic, rock bound coast and I see waves crashing against basalt cliffs. It is still sunny and the wind is blowing of the sea. Clouds billow and I stop several times to take photos.

I visit

another neolithic ring fort, Dunbeg, along the south Dingle coast.

This is privately owned. A new visitor center, made entirely out

of rock, is being constructed across the road from the fort. There

is a small hut where a woman, Kathy, takes a small fee for admittance.

I pay and head down the path in the cold wind. Again, I'm in my wind

gear and grateful for it. It is a small fort but obviously a stronghold

for some long gone clan. I examine the fort and look down the cliffs

at crashing waves. With it's back to the cliffs it would have been a hard

nut to crack!

I visit

another neolithic ring fort, Dunbeg, along the south Dingle coast.

This is privately owned. A new visitor center, made entirely out

of rock, is being constructed across the road from the fort. There

is a small hut where a woman, Kathy, takes a small fee for admittance.

I pay and head down the path in the cold wind. Again, I'm in my wind

gear and grateful for it. It is a small fort but obviously a stronghold

for some long gone clan. I examine the fort and look down the cliffs

at crashing waves. With it's back to the cliffs it would have been a hard

nut to crack!

Back up at the hut, I stick my head in the window and have a fine long chat with Kathy. There's a small propane heater burning which keeps her legs warm. She and her husband decided years ago to not sell the fort site to the Irish Government. The land has been in the family for several generations. They now are building the new visitor center at great expense, hoping to be able to support the family and eventually do even better. The tourist trade has been growing explosively, she says, and they wanted to keep control of the property. She has a sister who lives in Michigan and she's been to the USA a number of times. She says that with my face I look like I'm from the local neighborhood. "Until you spoke I thought you were from just down the road." I smile and thank her. I have felt at home with the people I've met here. At stores a couple people have confused me for some acquaintance. I look Irish, I guess.

Friday will be my last day in the west. In the early afternoon I head east, passing thru Tralee, and Limerick and then on to Tipperary. At Tipperary I stop at another work house cemetery, St. John's. This one is well kept and has a number of headstones in it. Along a wall there is a plaque commemorating the famine. There are also 12 stones engraved that commemorate the Stations of the Cross as Jesus headed toward his crucifixion. As I walk thru the cemetery I find a couple collapsed trenches. But they've been "gentled" over with dirt and grass. It is not the same forlorn site as was Ennistymon.

I stay

that night near Cashel where The

Rock, the ancient site of Brian O'Boru's Castle.

For the last 1000 years it has been the site of a cathedral, flanked by

an older round tower. This is one of the most famous sites of Ireland

for it was where St. Patrick had his base. Saturday

morning is sunny and I walk thru the Rock and a nearby abbey. The

town of Cashel is a busy town and obviously is set up for the tourist and

pilgrim trade. There are many B & B's and several hostels and a number

of gift shops in town. This is obviously a very busy place in the summer!!

Large parking lots are nearby to accommodate the tour buses and cars that

will fill them in a few months. Presently, the lots are nearly empty

on a Saturday morning.

I stay

that night near Cashel where The

Rock, the ancient site of Brian O'Boru's Castle.

For the last 1000 years it has been the site of a cathedral, flanked by

an older round tower. This is one of the most famous sites of Ireland

for it was where St. Patrick had his base. Saturday

morning is sunny and I walk thru the Rock and a nearby abbey. The

town of Cashel is a busy town and obviously is set up for the tourist and

pilgrim trade. There are many B & B's and several hostels and a number

of gift shops in town. This is obviously a very busy place in the summer!!

Large parking lots are nearby to accommodate the tour buses and cars that

will fill them in a few months. Presently, the lots are nearly empty

on a Saturday morning.

After the Rock, I turn toward the east and Dublin. It is time to get moving! I must find a B & B in the city and work out my "escape" to the airport. My flight will leave early on Sunday morning. I must drop off my rental car, find my terminal and make connections. That evening I stay at a B & B in a northern suburb. At the beginning of the week I was intimidated by the city. Driving on the left in heavy traffic was too much to consider and I had escaped to the north. Now I am fairly comfortable and so wander around in the northern suburbs of Dublin without any anxiety. Once I find the B & B, I am greeted by the owner, Patrick O'Reilly. "O'Rourke and O'Reilly from Breffny" he says. I nod and smile. We sit by the fire and talk. He has a gray beard and a ruddy face and is cheerful and chatty. Patrick is a retired "joiner" which means he was a cabinet maker. After retiring he worked part time as a teacher at the local trade college, helping train apprentices. He says he built all the furniture in the house. I look around at beautifully crafted chairs, dining room tables and cabinets with classic lines. I realize what a craftsman he is and compliment him. We chat amiably for quite a while. He does feel like an older cousin.

In the late afternoon I take the electric commuter train to downtown Dublin and walk about. On the train I ask a young women directions to downtown. Her name is Liz and soon we're deep in conversation. She's just back to Ireland, after being lived to the USA for 12 years. She's an aerobic instructor and personal trainer and she looks fit. We talk for quite a while. We get off the train downtown. We walk and she continues to talk. She misses the states! Now, in her early 30's, she doesn't feel at home any more in Dublin. It seems too small! Her friends have changed. When in the USA, she spent several years working at a ski resort in Colorado and spent another 5 years in New York. Too much has changed in Ireland and she wants to go back home to the states! I understand. As we talk, she shows me around downtown Dublin, pointing out Trinity College, statues to martyrs of the Easter Rebellion of 1916 and http://inac.org/history/1916.htmlothers sights. At some point she has to go. I thank Liz for her help and wish her well in her search for home. I walk thru the parks and visit Dublin Castle which was the headquarters of English rule in Ireland for many centuries. I see sites where the Easter Rebellion took place. Dublin is a vibrant city. Crowds head up and down it's narrow streets. Eventually it is time for me to head back to my B & B and settle down for the evening.

The next morning I am on my flight and I have time to contemplate my week, wandering over the face of Ireland. I've logged over 1200 miles and done the reconnaissance which I had intended.

Ireland is a small place geographically, when you compare it to the United States. I've told people it is "only" half the size of Wisconsin. Yet, how do you really take the measure of a place? And what is the best way to explore a place? In America, I am so used to jumping in a car and driving 1000 miles in less than a day to visit family or vacation. In Ireland, this is an immense distance. So, How do you measure Ireland? By it's recorded history? In that respect, it Ireland looms large over Wisconsin and Minnesota. Do you measure it by walking across it? Possibly by bicycle?

I have now been back in Wisconsin a little over a week and the journey has still not ended. I think about where I went and the individuals I met, write letters and contemplate the possibility of future visits to Ireland in the "off" months.

In most of the journeys I have taken, the focus has been on wilderness or climbing a particular mountain or cliff or paddling down a specific river. In this journey, my aims and experience was more diffuse. I was walking amongst people's graves, paying attention to those living whom I met in stores, in B & B's. I was feeling my way along, listening and trying not to focus too tightly on any one thing but rather to soak in a sense of the people and their place. I was also listening to my own reactions to the Irish. It was much more a contemplative rather than a physical journey.