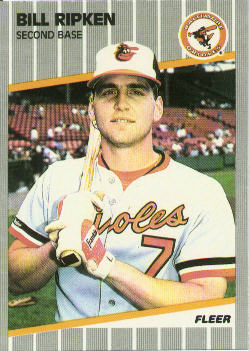

Bill Ripken

In 1989, the Fleer baseball card company produced a Billy Ripken card, which features on the batís face a phrase best left unprinted here. Word of the card spread among collectors, with the price rising to more than $100. Those hoping to get their hands on the card bought packs of randomly assorted cards at a torrid pace, and some in the industry attributed the 80 percent increase in sales of new cards that year in part to interest generated by the Ripken error.

This was not the first, or last, such mistake. The 1966 Topps Dick Ellsworth card contained a photo of Ken Hubbs, who died in 1964. The 1990 Topps Frank Thomas card, which features no name on the front, is the most valuable error card in recent memory, selling for as much as $1,000. This has led some, such as baseball card dealer John Benedetti of Bay State Coin Company in Boston, to wonder whether baseball card companies knowingly produce, or at least put into circulation, error cards as a way of generating publicity and boosting sales.

Clay Luraschi, a spokesman for Fleer/Skybox International, says the firm didnít produce the Ripken card intentionally and has never produced an error card intentionally, but that he cannot speak for other card companies. Rich Klein, an analyst at Beckett Baseball Card Monthly, an industry price guide, believes that although issuing error cards encourages collectors to spend a lot of money on packs in the short run, any such buying binge wonít last long, since companies stop printing the cards for a given season before the next season begins.

Although not everyone is convinced, even cynics agree that baseball card companies have reduced the profitability of error cards by limiting the frequency with which they issue correction cards. In the past, correction cards themselves sometimes became collectible. Fleer issued three correction cards for the 1989 Ripken error, one with the offending phrase whited out, another with it scribbled out, and a third with it blacked out. The whited out version now trades for as much as $30. However, according to Luraschi, the decision to stop producing corrections was largely due to their high cost.ď The printing process is very expensive and a reprint does not generate enough sales to pay for itself,Ē he notes.