A Coin For A Dance

2005

I don’t know what I thought I was going to do with them. Why would I ever bring a pair of black and white scissors on a trip to Trafalgar Square in the heart of London? And as I stood in line to enter yet another museum and walk past too many rows of paintings for too many hours, all so square, all so quiet, and all so prescribed, I knew I didn’t want to be there. I’d have to be still. The worst thing, though, was the line to the entryway, and the security; I didn’t want to go through the checkpoint with my favorite pair of scissors. They’d never failed me before since they can cut through anything, and they had stayed with me through various travels and moving across state, and I didn’t want them confiscated by a British security force at a museum I didn’t even want to go to. In Washington DC they took anything they suspected dangerous, usually anything pointed, and this queue had the same itch: wait to be patted down, wait to be treated subclass. They were just scissors.

“Hey guys, I don’t want to go in. Let’s split,” I said suddenly to the few girls that were with me, as if undeliberated and on a whim. I couldn’t go in; I couldn’t be still. The entire notion of the sterile museum was claustrophobic and confining, not to mention I really had to pee.

A friend, Julia, was at my side immediately, our eyes shifting quickly from the museum to the city--claustrophobic to grand. Stepping from the line, we disappeared quickly into the square.

____

Julia was in a prison of her cold as much as the museum would be to Tanna. It was another hall of paintings like the ones they had already seen in two prior museums and probably similar to masterpieces in subsequent visits during the weeks to follow. The city lay before the two, a grand tower in the square surrounded by four bronze lions, but as attractive as riding those massive beasts seemed, she needed to blow her nose and grab a fresh tissue, the one in her pocket now soggy ribbons, doing nothing to stop the spread of bacteria from her nose to her fingers. She felt so unclean that the bacterium were almost palpable, running in imaginary trails across her hands and under her nose.

She watched Tanna’s hurried search for a bathroom, following with as urgent, but a different, need. The bookstore didn’t have one, and neither did the drugstore. The tired Kleenex all to present in mind, she pointed to an American venue down the street and dashed forward, finally pushing the doors under golden arches open and stepping in line for the bathrooms near the door.

“Hey, Julia? This is really weird,” said Tanna.

“Huh?” Julia replied.

“Look.”

Realizing she had been nervously clenching the dead Kleenex in her pocket, she took her eyes off the tiled floor and looked up. UNISEX. There wasn’t a ladies room. No men’s room. Only one room to save space and promote gender equality. In front of them stood three dirty men, waiting to use the same stalls as they were. Her lip twitched.

“Hey, I don’t really need to use the toilet, so I’ll just wash my hands. Will you grab me some toilet paper when you’re done?” she asked Tanna, stepping from the line to the sink area.

She wanted to boil the bacterium off of her hands and destroy the remains with pink soap. The imagined processions of germs broke with an imaginary scream, and by the time the last microbe disappeared down the drain, Tanna was standing next to her washing her own hands.

“That’s just too weird. That’d never work in America. Do you know how many people would make a fuss over that?” Tanna asked, handing over the toilet paper.

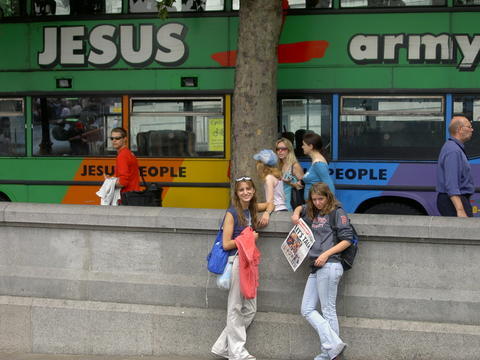

Julia took the tissue and put it in her pocket where the old one had been minutes before. Then she and Tanna heading back towards Trafalgar Square where a huge, exciting, and colorful rally for the Jesus Army was already going on, rainbow banners hanging from the tower in the middle of the square between each of the four huge lions at the corners of the tower’s platform. The Jesus Army blared Christian rock music over massive speakers, and even more loudly an announcer shouted praise to God.

“I am celibate for Jesus Christ! I will never have sex because it will ruin my relationship with Him. I’m doing it for Jesus!”

The organizers looked as if Jesus was their first step back from a hard life, as if they had a minute ago given up selling magazines on street corners (“Get The Big Issue, folks! Only 50 p! Get it now!”) to join the ranks of Christ’s army. One of them, a kind women, handed the two Jesus Army newspapers singing, “Thank you for coming for Jesus!” She turned away to another paperless group and left them stunned.

Julia thumbed through the paper, and, stepping slightly to the side, turned and saw a huge double-decker bus behind them with Jesus Army written across the side. Her eyes lit up. “Get in front of the bus for a picture. Hold up your papers! They have their own bus! That’s so great!”

Tanna grinned for the camera, Julia jumping up and down excitedly after the flash.

Lowering the camera, another half step brought a tent with faith healers into view. Then she turned slowly, taking in the whole spectacle for the first time. A man passed out plastic neon crosses on a hemp rope to celebrators passing by. Another sat on the walls of a grand fountain making cross balloon hats. Worshippers danced in front of the platform, swaying back and forth, murmuring to themselves. The whole scene was bizarre, a grand circus of balloons and stands and clowns. Julia almost expected the lions at each of the four corners to jump up, roar to the crowd, then leap through a ring of fire in the sky. She almost expected one of those kids with a cross hat to walk by with an elephant ear or a snow cone in hand.

On a note of frenzy, swept up in the excitement, Julia called to her friends, “Tanna, I’ll give you a pound to dance really crazy!”

She didn’t quite have her sentence finished and Tanna was already dancing. Tanna laughed and spun, waving her arms in the air like one of the worshippers, only faster, without faith’s passion; simply having fun. Julia handed over the pound, laughing too.

____

I had to find a bathroom, no question. A two hour trip from Cambridge to London on the bus with tea for breakfast created an emergency. I looked across the square, searching for businesses that always have public restrooms in the United States. If they wanted patronage, fine, I’d buy something, but the tea had had time to travel through my system during the bus ride and was ready to depart.

A bookstore. At home Borders and Barnes & Noble both had one, so the W.H. Smith in London, a pretty substantial establishment, should have one as well. No luck. Then we tried a drug store. No restrooms there either. Stepping out, I quickly looked up and down the street for anything else that looked promising and McDonald’s caught my eye. I ran, and so did Julia close behind.

Pushing the door open, half out of breath, I looked for the bathroom. UNISEX. That would never work in America. There would be a public outcry. I stepped in line behind a three filthy workmen waiting to use the same toilets I wanted to use. I felt uncomfortable as if I had found my way to the wrong line and everyone was staring at my folly. I thought any second the men would turn around and say, “The lady’s room is downstairs, miss.” I looked at the door again just to make sure it really did say “unisex.” UNISEX.

I turned to Julia behind me, whispering, “This is super weird.”

“Yeah, it’s strange,” she answered. “Hey, I’m just going wash my hands. Do you think you can grab me some toilet paper when you’re done?”

I joined her at the sink a few minutes later, saying more to myself than to her, “This really wouldn’t work in America. Do you know how many people would make a fuss these things?”

Hands clean, we stepped out of McDonalds, having purchased nothing, and headed back towards Trafalgar Square. There was a huge rally there, full of charismatic Christians, banners everywhere, and music I could feel through the bottoms of my feet--all around us was lots of color, people praying, and matching T-shirts. Looking over I saw a faith healer, cringing in my disdain for a practice that impinges upon real medical help. A child my friend knew as a little girl died because he went to a faith healer instead of going to the hospital. I turned away and saw children in balloon cross hats: pink cross hats, green cross hats, orange cross hats. I’m sure Jesus would have much rather worn a cross hat and look like a primary colored quail than have to wear a cross attached with nails. To the left, a man with Jesus Army newspapers. To the right a man had a handful of cheap orange crosses held by a cheaper cord. One for a little boy, one for a middle aged women. One, then two for us. I put it on, fearful that the cross would burn right through my chest. I’m not a “Jesus Freak.” I don’t have much faith.

Julia turned, her face lighting up as she saw the personal Jesus Army bus. “Get in front of the bus!” She pulled out her camera. “Hold up your newspapers! I can’t believe they have their own double decker bus! That’s so awesome!”

I posed, pointing at my paper, the huge rainbow bus behind me.

The event was a joke. Somewhere up there Jesus was laughing at what these people were doing in his name, laughing at a rally with matching shirts making a mockery of His pain on the cross, a comedy with brightly colored balloons and cross necklaces that say “Made in China” on the back.

“Tanna! I’ll give you a pound to dance around really crazy,” Julia shouted above the music.

I did it. There was no thought involved. Just movement. I was here in the middle of the craziest bunch of people in England (“Jesus gives a shout out to all those here from Birmingham!” the announcer called and cheers went up from part of the crowd). I was only movement, pure contraction and release of muscles to the sound and wild excitement of the rally. The opinions of these people meant nothing to me. I would never see them again.

Julia handed over the pound and we walked across the square to sit where it was quiet, waiting for friends who were still in the museum. I opened my backpack to put away my newspaper and saw the scissors at the bottom. I don’t know what I thought I would need them for, and they hadn’t been confiscated in security; today, because of them, there was no monotony, nothing prescribed.