The National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP)

India's National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP) was

established in 1962 and provided a system 446 District TB Centres, 330 TB

clinics, and more than -47,000 hospital beds – for TB control throughout the

country. After more than three decades of operation, the NTP can justly claim

to have established an infrastructure for tuberculosis treatment in India.

However, with a treatment completion rate of only 30 percent, the programme did

not make a significant dent in the problem.

Part of the difficulty undoubtedly lies in the perceived

priority of tuberculosis in India. One study of the problem from the Indian

Institute of Management, Ahmedabad found that tuberculosis had a low priority

compared to other diseases; funding was disproportionately low; senior

programme leaders did not remain in place for long: health staff were pressured

by non-TB activities; patients experienced indifferent programme delivery; and

the visibility of TB in the media was low.

Until

recently, tuberculosis has had a smaller central budget than malaria, leprosy,

blindness, or AIDS. Only guinea worm, among the priority communicable diseases,

received less. Negative expectations about the TB programme have tended to

become self-fulfilling.

In 1992, a review of the National

Tuberculosis Programme by national and international experts - in coordination

with the World Health Organization and the Swedish International Development

Association - determined that the programme had not had the desired impact on

tuberculosis in India. The review noted inadequate budgets, a lack of coverage

in some parts of the country, shortages of essential drugs, poor

administration, varying standards of care at the district centres, unmotivated

and unevenly trained staff, lack of equipment, poor quality of sputum

microscopy, and focus on case detection without an accompanying emphasis on

treatment outcomes. There was a general consensus that, in a revised

tuberculosis control programme, the patient would have to be both the starting

point and the focus, It is therefore essential to understand the patterns of

diagnosis and treatment from the patient's perspective.

"Health-Seeking

Behaviour of Chest Symptomatics"

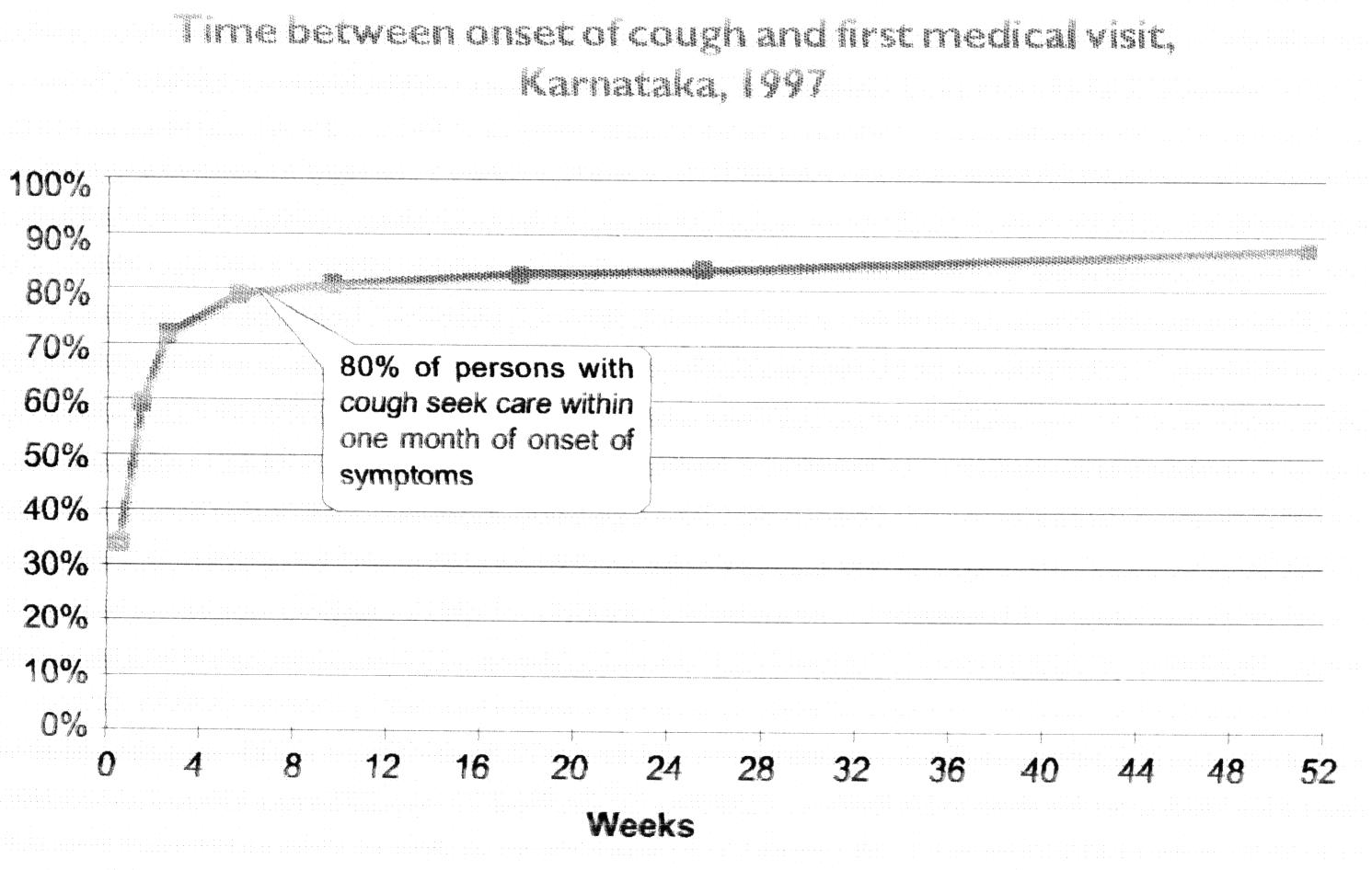

In India, the vast majority of

patients with active tuberculosis seek treatment for their disease, and do so

promptly. However, many patients spend a great deal of time and money

"shopping for health" before they begin treatment, and, all too

often, they do not receive either accurate diagnosis or effective treatment,

despite spending considerable resources. In a community-based systematic survey

in Karnataka, cough for three weeks or more was present in 1.4% of

people; rates increased with age, and were higher among males than among

females (See figure). Patients usually visit a number of health providers -

from general practitioners and general hospitals to practitioners of indigenous

medicines and even quacks. Unqualified rural practitioners are the first

point of contact for many TB patients.

This study also found that patients almost always seek care

promptly. The average time it takes for a patient to visit a health facility

after the appearance of symptoms was less than 2 weeks. Virtually all

symptomatic patients who sought care did so within one month of the onset of

symptoms. In areas with better performing health systems, patients sought care

even more promptly. The only sub-group which did not seek care promptly was

elderly, non-literate males.

Delay between the onset of symptoms and the start of

effective treatment is important in the control of tuberculosis because during

this rime patients are most infectious. Most delay in diagnosis is on the part

of the health system, not patients.

One barrier to treatment is the stigma that is still

associated with tuberculosis. In many parts of India, this remains a serious

problem.

In one recent study, researchers interviewed several

hundred patients and their families and found that most patients felt

uncomfortable talking about tuberculosis. Several patients denied that they

were suffering from the disease or taking treatment for it, and some even

refused to mention tuberculosis by name. Patients frequently attempted to hide

their disease from their family and community by registering under false names

at tuberculosis clinics or by denying their identity when confronted by

interviewers.

Similarly a study by the Indian institute of Management

found that most patients were reluctant to admit that they had TB because they

feared stigma, and they preferred not to discuss the disease in the presence of

family or neighbors. This was more so in urban than in rural areas. Family support

for treatment was more frequent among cured patients than among those who had

defaulted.

|

First action taken by chest symptomatics

|

|

|

Mysore district

|

Raichur district

|

Tamil Nadu

|

Delhi

%

|

Average

%

|

|

Rural

%

|

Urban

%

|

Rural

%

|

Urban

%

|

Rural

%

|

Urban

%

|

|

Private provider

|

48

|

76

|

93

|

74

|

48

|

57

|

55

|

64

|

|

Government facility

|

51

|

22

|

5

|

25

|

46

|

32

|

21

|

29

|

|

Self-medication

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

4

|

8

|

10

|

3

|

|

Home remedies

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

1

|

2

|

6

|

1

|

|

Others

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

8

|

2

|

|

Total taking

action

|

83

|

85

|

90

|

85

|

63

|

80

|

82

|

81

|

|

No action prior to

interview

|

17

|

15

|

10

|

15

|

37

|

20

|

18

|

19

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The majority of TB patients in India who seek help first

consult one of India's 10 million private medical practitioners (See previous

tables). In studies that assessed the health-seeking behaviour of chest symptomatics in rural Karnataka and Tamil Nadu,

and in urban Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Delhi, researchers found that 64 percent

first sought help from a private provider Only 29 percent went to a government

facility on the first visit. Ramana et al. found that 80 percent of all private

practitioners in their study areas in rural and urban Andhra Pradesh were

treating tuberculosis.

The major causes patients gave for seeking private

providers were proximity and convenient working hours; while the main reason

for going to government facilities was free treatment.

Studies have shown that, despite having limited

resources, most patients are not promptly diagnosed and treated, and therefore

go from one doctor to the next before a diagnosis is firmly established and

treatment begins.

In one study, the average number of health providers

visited by patients from the time they developed symptoms to the time they

registered at a TB clinic was 2.5 for urban patients and 4.0 for rural patients.

Not only did this increase the cost of treatment, increasing debt, but it also

delayed prompt initiation of treatment, thus avowing disease to spread further

in the community.

The total cost incurred by patients shopping for care was

about Rs 1000 ($30) in urban and Rs 630 ($18) in rural Karnataka, and about Rs 550 ($16) and Rs 400 ($11)

in urban and rural Tamil Nadu.

All too often, health providers

fail to diagnose the disease correctly, thereby delaying the start of treatment

and perpetuating the chain of infection in the community

|

Provider consulted first by patients with

tuberculosis

|

|

Provider Consulted First

|

Medak (rursal)%

|

Hyderabad (urban)%

|

Unqualified neighborhood doctor

|

7.1

|

1.5

|

|

Qualified neighborhood doctor

|

25.7

|

55.2

|

|

Doctor (not aware of qualifications)

|

41.5

|

20.9

|

|

Specialist in TB/Chest Diseases

|

0

|

.7

|

|

Specialty Hospital

|

8.6

|

0

|

|

Clinic/Dispensary/PHC

|

4.3

|

3

|

|

Hospital

|

1.4

|

14.9

|

|

TB Clinic/Hospital

|

11.4

|

3.8

|

Source: Mapping of TB Treatment Providers at Selected Sites in Andhra

Praradesh State,

Many providers do not confirm their diagnosis of pulmonary

tuberculosis by sputum examination, relying instead on chest radiographs and

thus often incorrectly diagnosing patients to have tuberculosis, in one study

in Bombay, only 39 percent of doctors used sputum examination to confirm the

diagnosis of tuberculosis. Studies in Delhi, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu revealed

that, even after multiple visits, less than one third of patients underwent

sputum smear examination. In one study, even after 8 encounters with the health

system, less than one third of patients had undergone even a single sputum

examination, despite spending 1-6 months of their income, in rural areas, lack

of access to effective diagnosis and treatment was even more pronounced (See

figure).

Even when tuberculosis is diagnosed by private

practitioners, prescribing practices vary widely. A study of 100 private

doctors in Bombay, found that there were 80 different regimens, most of which

were either inappropriate or expensive, or both. In a similar survey in Pune,

113 doctors prescribed 90 different regimens. Private doctors seldom felt that

it was their duty to educate the patients about TB and never made attempts to

contact or trace patients who had interrupted treatment. Virtually no

individual patient records are maintained by private physicians.

Even when patients are eventually diagnosed and then

prescribed the correct treatment regimen, many discontinue it if they are not

supported and monitored throughout the treatment period. The two main reasons

offered by the majority of those who stopped treatment were that they felt

better and had therefore discontinued their drugs, and that there was too much

cost and trouble associated with getting an uninterrupted supply of drugs.

Estimates in India indicate that, of every 100 infectious

tuberculosis cases in the community, about 30 are identified in the public

sector, of which at most 10 are cured; similarly, about 30 are identified in

the private sector, of which at most 10 are cured. Hence, not more than 20

percent of patients who develop tuberculosis in India each year are cured. Many

of the remaining patients remain chronically ill or die slowly from the

disease, infecting others with strains of the disease which may have developed

drug resistance.

Despite these serious shortcomings, there are signs of

hope. Most practicing physicians reported that they would be interested in

receiving training on DOTS, and most were willing to have their offices used as

centres for treatment observation for their patients, free of charge.

How is TB disease treated in India?

There are many possible anti-TB treatment regimens. The World Health

Organization (WHO) and the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung

Disease (IUATLD) recommend standardized TB treatment regimens.

The most common drugs used to fight TB (when used in combination of more

than one drug, called a "regimen") are:

· isoniazid

(INH or H)

·

rifampicin (R)

·

pyrazinamide (Z)

·

ethambutol (E)

·

streptomycin (S)

Based on case- definition, a TB patient may fall into any one of the

following four categories for treatment. The categories are numbered in order

of priority. The highest priority for treatment is Category 1 patients and the

lowest priority is Category 4:

Category 1: New cases who

are smear-positive, or seriously ill patients who are smear-negative or who

have extra-pulmonary disease.

Category 2: Re-treatment

cases including patients with relapse, treatment failure and those who return

to treatment after default. Such patients are generally sputum-positive.

Category 3: Patients who

are sputum-negative, or who have extra-pulmonary TB and are not seriously ill.

Category 4: Chronic cases,

still sputum-positive after supervised re-treatment

Treatment regimens usually comprise two phases: the Intensive phase and the

continuation phase. There are several possible regimens for treating each

category of TB. Suggested alternatives are given in the following table.

However, it is important to stress that in a given country, the

regimen recommended by the National TB Programme, which is described in the NTP

Manual, should be followed.

Table 1 Possible alternate

treatment regimens for each treatment category

|

TB treatment category

|

Alternative TB treatment Regimens

|

|

Initial Phase

(daily or 3 times a week)

|

Continuatioin phase

|

|

I

|

2 EHRZ (SHRZ)*

2 EHRZ (SHRZ)

2 EHRZ (SHRZ)

|

6 HE*

4 HR

4 H2R3

|

|

II

|

2 EHRZ (SHRZ)/ 1

HRZE

2 EHRZ (SHRZ)/ 1 HRZE

|

5 H3R3E3

5 HRE

|

|

III

|

2 HRZ

2 HRZ

2 HRZ

|

6 HE

4 HR

4 H3R3

|

|

IV

|

Not Applicable

(Refer to WHO guidelines for use of

second-line drugs in specialized centres )

|

* A standard code is used for

each drug. For example, the regimen of 2HRZE(S)/4HR has two phases

· The

intensive phase (2HRZE) means daily treatment with a combination of four drugs

for two months: isoniazid (H), rifampicin (R), pyrazinamide (Z) and ethambutol

(E). The last drug (E) and streptornycin (S) can be interchanged where either

one or the other of the two drugs is available.

·

The continuation phase (4HR) means daily treatment with

isoniazid (H) and rifampicin (R) for four months

For the regimen 2HRZE(S)/4H3,R3, the abbreviation H3R3 means a treatment

three times a week with both isoniazid and rifampicin.

|

Anti-TB Drug

(Abbreviation)

|

Recommended Dose (mg/ kg)

|

|

|

Daily

|

Intermittent

3x /wk

|

|

Isoniazid(H)

|

5(4-6)

|

10(8-12)

|

|

Rifampicin (R)

|

10(8-12)

|

10(8-12)

|

|

Pyrazinamide (Z)

|

25(20-30)

|

35(30-40)

|

|

Streptornycin (S)

|

15(12-18)

|

15(12-18)

|

|

Ethambutol (E)

|

15(15-20)

|

30(25-35)

|

|

Thiacetazone(T)

|

2.5

|

Not Applicable

|

All these anti-TB drugs should be given as as a single daily dose. Direct

observation is recommended for all patients and is particularly essential when

intermittent regimens are used. Thiacetazone is not effective when given

intermittently and is not recommended for use in high HIV prevalence areas.

The

side-effects of anti-TB drugs

The side effects of individual anti-TB drugs are shown in the table below.

They are classified as minor or major. In general, a patient who develops minor

side effects should continue the anti-TB treatment, usually at the same dose or

if necessary at a reduced dose. The patient should also receive symptomatic

treatment. If a patient develops a major side effect, the treatment or the

offending drug should be stopped.

|

Table 2 Side-effect of anti-TB drugs

|

Side-effects

|

Drug(s) probably responsible

|

Minor

|

|

1

|

anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain

|

|

2

|

joint pain

|

|

3

|

burning sensation in the feet

|

|

4

|

orange/ red urine

|

|

rifampicin

pyrazinamide

isoniazid

rifampicin

|

Major

|

|

1

|

itching of skin, skin rash

|

|

2

|

deafness

|

|

3

|

dizziness

|

|

4

|

jaundice

|

|

5

|

vomiting and confusion

|

|

6

|

visual impairment

|

|

7

|

shock, purpura, acute renal failure

|

|

thiacetazone (streptomycin)

streptomycin

streptomycin

most anti-TB drugs (esp. H,Z,R)

most anti-TB drugs

ethambutol

rifampicin

|

Are the side-effects or toxicity

due to anti-TB drugs more common in HIV-positive Individuals?

Adverse reactions are

generally more common in HIV-positive than in HIV-negative TB patients. Most

reactions occur in the first two months of treatment. Skin rash and hepatitis

are more common and most often attributed to rifampicin. The usual drug

responsible for fatal skin reaction such as exfoliative dermatitis,

Steven-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis is thiacetazone.

Therefore, thiacetazone should never be given to HIV-positive TB patients. From

a programmatic point of view, thiacetazone should not be prescribed in areas

where HIV prevalence is shown to be high.

Key Findings and implications for

Action

Patients with symptoms of TB seek care promptly - but in

both the public and the private system, they are neither reliably diagnosed nor

effectively treated. Where services are better people use them more promptly

and more often despite 8 encounters with the health system and the expenditure

of 1-6 months' wages, less than one third of patients with symptoms of TB had

undergone even a single sputum examination for AFB! in both public and private

sectors, successful treatment of tuberculosis is the exception rather than the

norm.

• The behavior of patients does

not need to be changed - the health system's response to this behavior must

improve.

• Diagnostic

practices need to be strengthened urgently. In both public and private primary

health care systems health workers need to "Think TB" and ensure that

all adult patients are asked whether or not they have cough for 3 weeks, and,

if they do, that they undergo 3 sputum examinations in a good quality

laboratory.

• Programme managers need to publicize the location and

availability of free sputum microscopy centres, and the fact that 3 sputum

samples should be examined if patients have cough for 3 weeks or more.

• Programme managers need to involve both qualified and

unqualified practitioners to refer patients for diagnosis.

• Practicing

physicians should ensure that every patient with symptoms of TB undergoes 3

sputum examinations in a quality-controlled laboratory, preferably by referring

such patients to an RNTCP microscopy centre.

• In

public and private sectors, improved interpersonal communication, standardized

treatment, direct observation at a time and place convenient to patients, and

systematic monitoring and accountability are needed urgently.