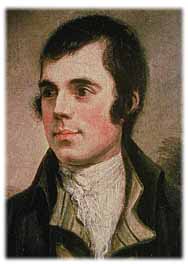

Born in

Alloway, Ayrshire, in 1759 to William Burness, a poor tenant farmer, and Agnes

Broun, Robert Burns was the eldest of seven. He spent his youth working his

father's farm, but in spite of his poverty he was extremely well read - at the

insistence of his father, who employed a tutor for Robert and younger brother

Gilbert. At 15 Robert was the principal worker on the farm and this prompted

him to start writing in an attempt to find "some kind of counterpoise for

his circumstances." It was at this tender age that Burns penned his first

verse, "My Handsome Nell", which was an ode to the other subjects

that dominated his life, namely scotch and women.

Born in

Alloway, Ayrshire, in 1759 to William Burness, a poor tenant farmer, and Agnes

Broun, Robert Burns was the eldest of seven. He spent his youth working his

father's farm, but in spite of his poverty he was extremely well read - at the

insistence of his father, who employed a tutor for Robert and younger brother

Gilbert. At 15 Robert was the principal worker on the farm and this prompted

him to start writing in an attempt to find "some kind of counterpoise for

his circumstances." It was at this tender age that Burns penned his first

verse, "My Handsome Nell", which was an ode to the other subjects

that dominated his life, namely scotch and women.

When his father died in 1784, Robert and his brother became partners in the

farm. However, Robert was more interested in the romantic nature of poetry

than the arduous graft of ploughing and, having had some misadventures with

the ladies (resulting in several illegitimate children, including twins to the

woman who would become his wife, Jean Armour), he planned to escape to the

safer, sunnier climes of the West Indies.

However, at the point of abandoning farming, his first collection

"Poems- Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect - Kilmarnock Edition" (a set

of poems essentially based on a broken love affair), was published and

received much critical acclaim. This, together with pride of parenthood, made

him stay in Scotland. He moved around the country, eventually arriving in

Edinburgh, where he mingled in the illustrious circles of the artists and

writers who were agog at the "Ploughman Poet."

In a matter of weeks he was transformed from local hero to a national

celebrity, fussed over by the Edinburgh literati of the day, and Jean Armour's

father allowed her to marry him, now that he was no longer a lowly wordsmith.

Alas, the trappings of fame did not bring fortune and he took up a job as an

exciseman to supplement the meagre income. Whilst collecting taxes he

continued to write, contributing songs to the likes of James Johnston's

"Scot's Musical Museum" and George Thomson's "Select Collection

of Original Scottish Airs." In all, more than 400 of Burns' songs are

still in existence.

The last years of Burns' life were devoted to penning great poetic

masterpieces such as The Lea Rig, Tam O'Shanter and a Red, Red Rose. He died

aged 37 of heart disease exacerbated by the hard manual work he undertook when

he was young. His death occurred on the same day as his wife Jean gave birth

to his last son, Maxwell.

On the day of his burial more than 10,000 people came to watch and pay

their respects. However, his popularity then was nothing compared to the

heights it has reached since.

On the anniversary of his birth, Scots both at home and abroad celebrate

Robert Burns with a supper, where they address the haggis, the ladies and

whisky. A celebration which would undoubtedly make him proud.

Auld Lang Syne

Burns has described this as an old song and tune which had often thrilled through his soul; and in communicating it to his friend George Thomson, he professed to have recovered it from an old man's singing; and exclaimed regarding it--"Light be the turf on the breast of the Heaven-inspired poet who composed this glorious fragment!" The probability is, however, that the poet was indulging in a little mystification on the subject, and that the entire song was his own composition. The second and third verses--describing the happy days of youth--are his beyond a doubt.

SHOULD auld acquaintance be forgot,

And never brought to min'?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And days o' lang syne?

CHORUS

For auld lang syne, my dear,

For auld lang syne,

We'll tak a cup o' kindness yet

For auld lang syne !

We twa hae run about the braes,

And put't the gowans fine ;

But we've wander'd mony a weary foot

Sin' auld lang syne !

For auld &c.

We twa hae paidlet i' the burn,

Frae mornin sun till dine :

But seas between us braid hae roar'd

Sin' auld lang syne.

For auld &c.

And here's a hand, my trusty fiere,1.

And gie's a hand o' thine ;

And we'll tak a right gude willie-waught,2.

For auld lang syne !

For auld &c.

And surely ye'll be your pint-stowp,

And surely I'll be mine ;

And we'll tak a cup o' kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

For auld &c.

SCOTS, WHA HAE

Bruce's Address to His Army at Bannockburn

TUNE--"Hey, tuttie taitie."

"There is a tradition," says the poet, in a letter to Thomson, enclosing this glorious ode, "that the old air 'Hey, tuttie taitie,' was Robert Bruce's march at the battle of Bannockburn. This thought, in my solitary wanderings, has warmed me to a pitch of enthusiasm on the theme of liberty and independence which I have thrown into a kind of Scottish ode, fitted to the air, that one might suppose to be the gallant Scot's address to his heroic followers on that eventful morning." This ode, says Professor Wilson--the grandest out of the Bible--is sublime!

SCOTS, wha hae wi' WALLACE bled,

Scots, wham Bruce has aften led,

Welcome to your gory bed

Or to Victory!

Now's the day, and now's the hour:

See the front o' battle lour;

See approach proud Edwards power-

Chains and slavery!

Wha will be a traitor knave?

Wha can fill a cowards grave?

Wha sae base as be a slave?

Let him turn, and flee!

Wha for SCOTLAND'S king and law,

FREEDOM'S sword will strongly draw;

Freeman stand or freeman fa',

Let him follow me!

By Oppression's woes and pains!

By your sons in servile chains!

We will drain our dearest veins,

But they shall be free!

Lay the proud usurpers low!

Tyrants fall in every foe!

LIBERTY'S in every blow!--

Let us do, or die!

![]()